Abstract

BACKGROUND—Decreased synthesis of the predominant secretory human colonic mucin (MUC2) occurs during active ulcerative colitis. AIMS—To study possible alterations in mucin sulphation and mucin secretion, which could be the cause of decreased mucosal protection in ulcerative colitis. METHODS—Colonic biopsy specimens from patients with active ulcerative colitis, ulcerative colitis in remission, and controls were metabolically labelled with [35S]-amino acids or [35S]-sulphate, chase incubated and analysed by SDS-PAGE, followed by quantitation of mature [35S]-labelled MUC2. For quantitation of total MUC2, which includes non-radiolabelled and radiolabelled MUC2, dot blotting was performed, using a MUC2 monoclonal antibody. RESULTS—Between patient groups, no significant differences were found in [35S]-sulphate content of secreted MUC2 or in the secreted percentage of either [35S]-amino acid labelled MUC2 or total MUC2. During active ulcerative colitis, secretion of [35S]-sulphate labelled MUC2 was significantly increased twofold, whereas [35S]-sulphate incorporation into MUC2 was significantly reduced to half. CONCLUSIONS—During active ulcerative colitis, less MUC2 is secreted, because MUC2 synthesis is decreased while the secreted percentage of MUC2 is unaltered. Furthermore, sulphate content of secreted MUC2 is unaltered by a specific compensatory mechanism, because sulphated MUC2 is preferentially secreted while sulphate incorporation into MUC2 is reduced.

Keywords: ulcerative colitis; mucin; MUC2; sulphation; secretion

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (141.3 KB).

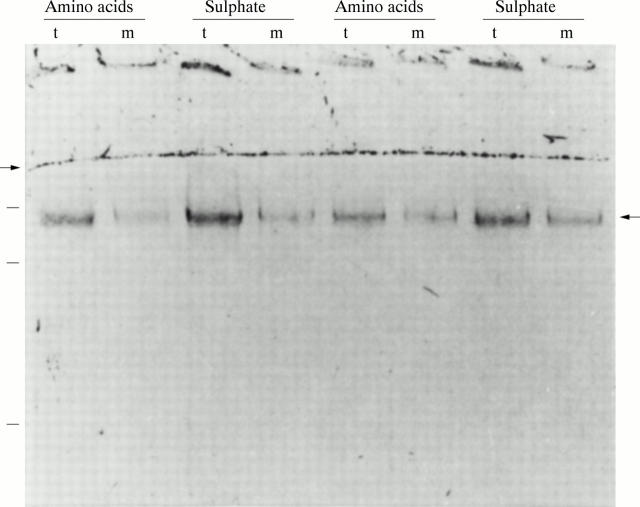

Figure 1 .

PAS staining of mature MUC2. A representative example of analyses of duplicate biopsy specimens of one control patient. After pulse labelling with either [35S]-amino acids or [35S]-sulphate and four hour chase incubations, the homogenates of the tissue (t) and the media (m) were analysed on reducing 4% SDS-PAGE and stained with PAS. The right hand arrow indicates the position of mature MUC2. The left hand arrow denotes the border between the running and stacking gel. Molecular mass markers of 600, 300, and 205 kDa are indicated on the left.

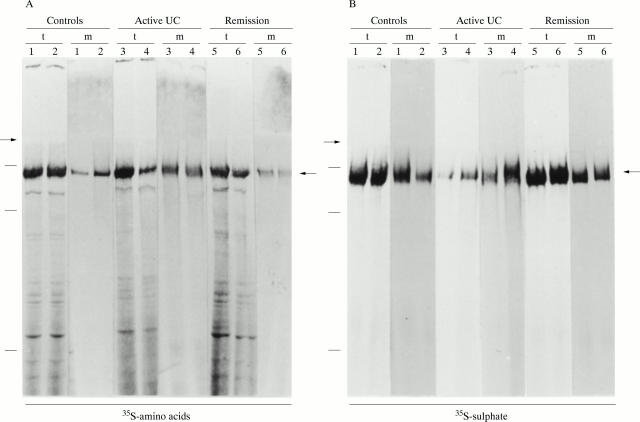

Figure 2 .

Identification of mature MUC2 in colonic homogenates. Representative examples of analyses of the biopsy specimens of each patient group are shown: controls (specimens 1 and 2), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (specimens 3 and 4), or ulcerative colitis in remission (specimens 5 and 6). Specimens were pulse labelled with either (A) [35S]-amino acids (two duplicate specimens per patient) or (B) [35S]-sulphate (two duplicate specimens per patient) and chase incubated for four hours, followed by analysis of the homogenates of the tissue (lanes t) and of the media (lanes m) on 4% reducing SDS-PAGE. The radioactive signal of the mature MUC2 band, indicated by the right hand arrows, was quantified using a PhosphorImager, followed by exposure to x ray film (shown here). The left hand arrows denote the border between the running and stacking gel. Molecular mass markers of 600, 300, and 205 kDa are indicated on the left.

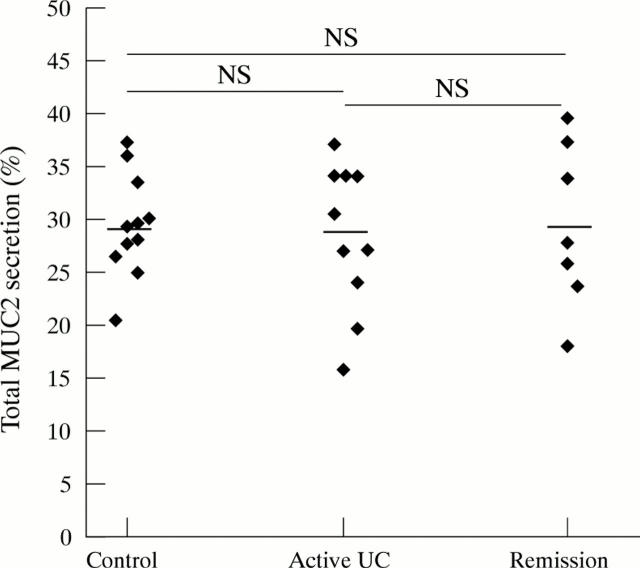

Figure 3 .

Secretion of total MUC2. All 35S-labelled homogenates were dot blotted and incubated with an anti-MUC2 monoclonal antibody and 125I-labelled protein A. The elicited 125I signal was then quantified and the secreted percentage of total MUC2 was calculated. Average values were then calculated per patient from the quadruplicate values of the biopsy specimens, and the mean values per patient group were subsequently calculated. Each point represents the average value of one patient. Mean (SEM) value per patient group: controls (29.5 (1.41)%), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (28.5 (2.21)%) and ulcerative colitis in remission (29.4 (2.9)1%). Horizontal bars denote the mean of each patient group.

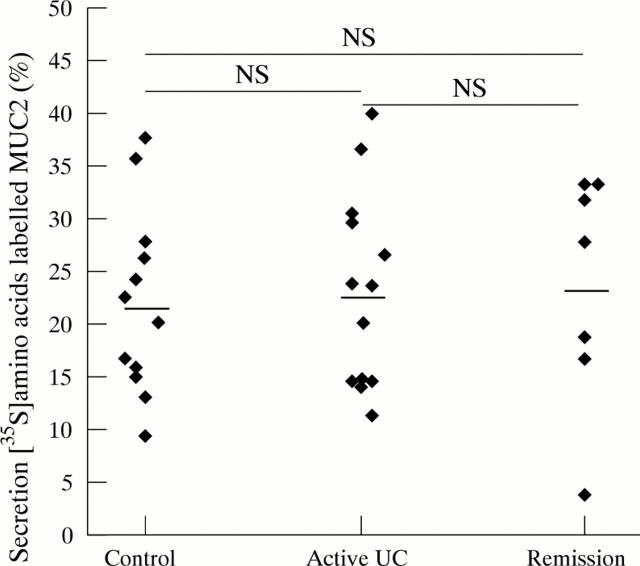

Figure 4 .

Secretion of [35S]-amino acid labelled MUC2. [35S]-amino acid labelled homogenates were analysed on reducing SDS-PAGE, and the MUC2 band was quantified. The secreted percentage of MUC2 was calculated per biopsy specimen. Average values were calculated per patient from the duplicate values of the specimens, and the mean values per patient group were determined. Each point represents the average value of one patient. Mean (SEM) values per patient group: controls (22.17 (2.55)%), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (23.08 (2.55)%) and ulcerative colitis in remission (23.47 (4.16)%). Horizontal bars denote the mean of each patient group.

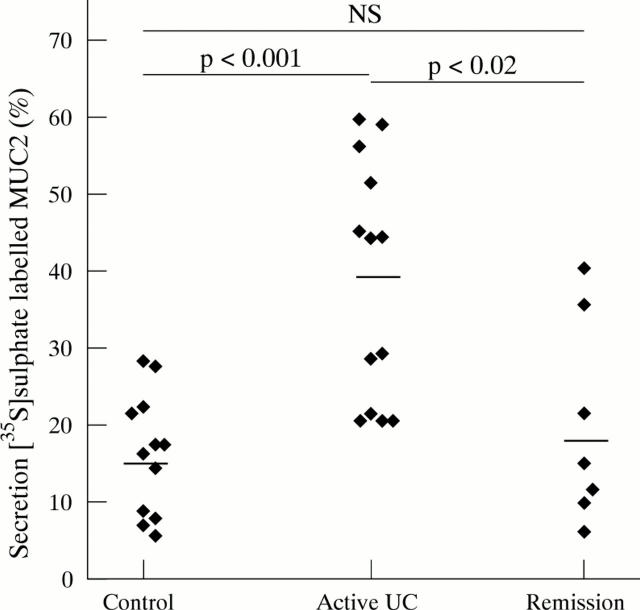

Figure 5 .

Secretion of [35S]-sulphate labelled MUC2. [35S]-sulphate labelled homogenates were analysed on reducing SDS-PAGE, and the MUC2 band was quantified. The secreted percentage of MUC2 was calculated per biopsy specimen. Average values were calculated per patient from the duplicate values of the specimens, and the mean values per patient group were determined. Each point represents the average value of one patient. Mean (SEM) values per patient group: controls (16.23 (2.27)%), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (38.63 (4.3)%) and ulcerative colitis in remission (19.97 (2.27)%). Horizontal bars denote the mean of each patient group.

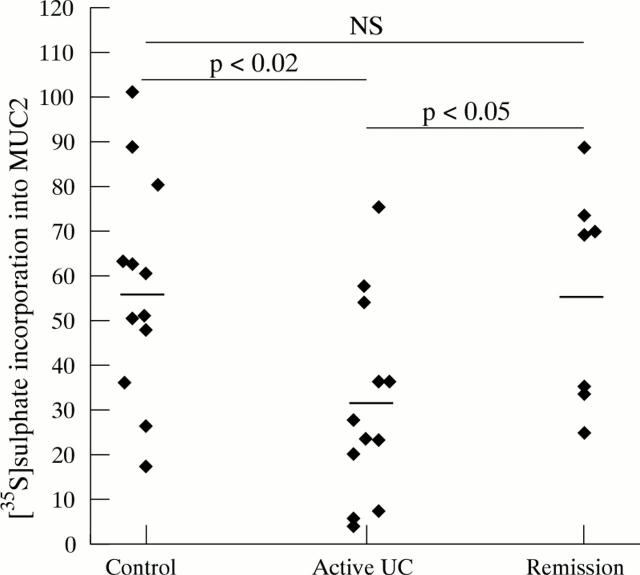

Figure 6 .

[35S]-sulphate incorporation into MUC2. To determine [35S]-sulphate incorporation into MUC2, the sum of the amounts of [35S]-sulphate labelled MUC2 in tissue and media homogenates was expressed relative to the sum of the amounts of [35S]-amino acid labelled MUC2 in tissue and media homogenates. Each point represents one patient. Mean (SEM) values per patient group: controls (57.35 (7.1)), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (31.04 (6.43)) and ulcerative colitis in remission (56.63 (9.28)). Horizontal bars denote the mean of each patient group.

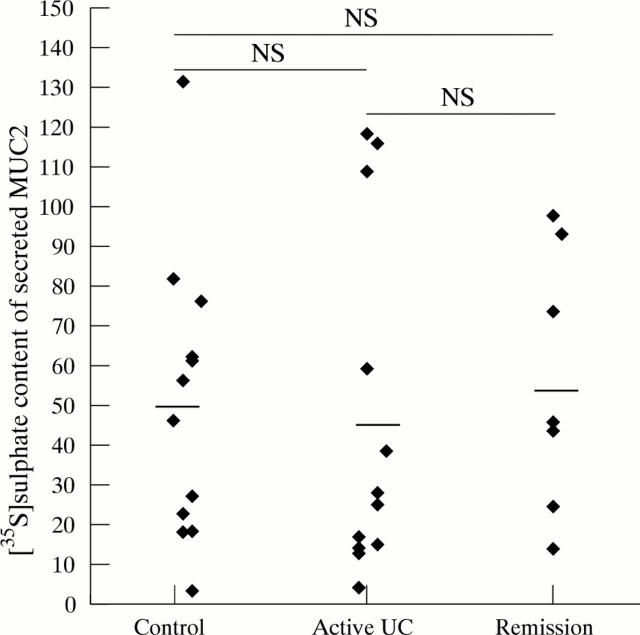

Figure 7 .

[35S]-sulphate content of secreted MUC2. To determine [35S]-sulphate content of secreted MUC2, the amount of [35S]-sulphate labelled MUC2 in the medium was expressed relative to the amount of [35S]-amino acid labelled MUC2 in the medium. Each point represents one patient. Mean (SEM) values per patient group: controls (50.23 (10.33)), active ulcerative colitis (UC) (46.14 (12.59)) and ulcerative colitis in remission (55.91 (12.5)). Horizontal bars denote the mean of each patient group.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dekker J., Strous G. J. Covalent oligomerization of rat gastric mucin occurs in the rough endoplasmic reticulum, is N-glycosylation-dependent, and precedes initial O-glycosylation. J Biol Chem. 1990 Oct 25;265(30):18116–18122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L. R., Huber P. W. Regional distribution and alterations of lectin binding to colorectal mucin in mucosal biopsies from controls and subjects with inflammatory bowel diseases. J Clin Invest. 1985 Jan;75(1):112–118. doi: 10.1172/JCI111662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick D. A., Horton L. W., Mee A. S. Mucin depletion in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Pathol. 1990 Feb;43(2):143–146. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.2.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morita H., Kettlewell M. G., Jewell D. P., Kent P. W. Glycosylation and sulphation of colonic mucus glycoproteins in patients with ulcerative colitis and in healthy subjects. Gut. 1993 Jul;34(7):926–932. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.7.926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nieuw Amerongen A. V., Bolscher J. G., Bloemena E., Veerman E. C. Sulfomucins in the human body. Biol Chem. 1998 Jan;379(1):1–18. doi: 10.1515/bchm.1998.379.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker N., Tsai H. H., Ryder S. D., Raouf A. H., Rhodes J. M. Increased rate of sialylation of colonic mucin by cultured ulcerative colitis mucosal explants. Digestion. 1995;56(1):52–56. doi: 10.1159/000201222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky D. K. Inflammatory bowel disease (2) N Engl J Med. 1991 Oct 3;325(14):1008–1016. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199110033251406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullan R. D., Thomas G. A., Rhodes M., Newcombe R. G., Williams G. T., Allen A., Rhodes J. Thickness of adherent mucus gel on colonic mucosa in humans and its relevance to colitis. Gut. 1994 Mar;35(3):353–359. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.3.353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raouf A. H., Tsai H. H., Parker N., Hoffman J., Walker R. J., Rhodes J. M. Sulphation of colonic and rectal mucin in inflammatory bowel disease: reduced sulphation of rectal mucus in ulcerative colitis. Clin Sci (Lond) 1992 Nov;83(5):623–626. doi: 10.1042/cs0830623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E., Moore J., Babidge W. Colonic sulfide in pathogenesis and treatment of ulcerative colitis. Dig Dis Sci. 1997 Aug;42(8):1571–1579. doi: 10.1023/a:1018851723920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strous G. J., Dekker J. Mucin-type glycoproteins. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 1992;27(1-2):57–92. doi: 10.3109/10409239209082559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRUELOVE S. C., RICHARDS W. C. Biopsy studies in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1956 Jun 9;1(4979):1315–1318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4979.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theodossi A., Spiegelhalter D. J., Jass J., Firth J., Dixon M., Leader M., Levison D. A., Lindley R., Filipe I., Price A. Observer variation and discriminatory value of biopsy features in inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 1994 Jul;35(7):961–968. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.7.961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat K. M., Büller H. A., Opdam F. J., Kim Y. S., Einerhand A. W., Dekker J. Biosynthesis of human colonic mucin: Muc2 is the prominent secretory mucin. Gastroenterology. 1994 Nov;107(5):1352–1363. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat K. M., Klomp L. W., Bovelander F. J., Opdam F. J., Van der Wurff A., Einerhand A. W., Büller H. A., Strous G. J., Dekker J. Preparation of anti-mucin polypeptide antisera to study mucin biosynthesis. Anal Biochem. 1995 Apr 10;226(2):331–341. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat K. M., Opdam F. J., Einerhand A. W., Büller H. A., Dekker J. MUC2 is the prominent colonic mucin expressed in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1996 Apr;38(4):554–563. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.4.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat K. M., Swallow D. M., Van Klinken B. J., Büller H. A., Einerhand A. W., Dekker J. Unpredictable behaviour of mucins in SDS/polyacrylamide-gel electrophoresis. Biochem J. 1995 Sep 15;310(Pt 3):1053–1054. doi: 10.1042/bj3101053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tytgat K. M., van der Wal J. W., Einerhand A. W., Büller H. A., Dekker J. Quantitative analysis of MUC2 synthesis in ulcerative colitis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996 Jul 16;224(2):397–405. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Klinken B. J., Dekker J., Büller H. A., Einerhand A. W. Mucin gene structure and expression: protection vs. adhesion. Am J Physiol. 1995 Nov;269(5 Pt 1):G613–G627. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1995.269.5.G613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Klinken B. J., Dekker J., Büller H. A., de Bolòs C., Einerhand A. W. Biosynthesis of mucins (MUC2-6) along the longitudinal axis of the human gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol. 1997 Aug;273(2 Pt 1):G296–G302. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]