Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—Dietary fibre influence growth and function of the upper gastrointestinal tract. This study investigates the importance of dietary fibre in intestinal growth in experimental diabetes, and correlates intestinal growth with plasma levels of the intestinotrophic factor, glucagon-like peptide 2 (GLP-2). METHODS—Male Wistar rats were randomised to the following groups: two streptozotocin-diabetic and two control groups fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet for three weeks. Intestinal weight, length, and morphometric data (villus height, villus area, crypt depth) were measured. Blood samples were obtained after two weeks for measurement of GLP-2 and enteroglucagon (glicentin, oxyntomodulin). RESULTS—The mean daily consumption of food in the two diabetic groups was 40% higher than in controls. In diabetic rats fed fibre, the increase in intestinal weight from day 0 to 20 was sixfold greater than that of the controls and small intestine weight per cm length was increased by 50%. In the diabetic rats fed a fibre-free diet, intestinal growth was 30% less than in diabetic rats fed fibre, and intestinal weight increased only threefold compared with controls. Morphometric data showed that the intestinal increase in diabetic rats fed fibre was due primarily to growth of the mucosal layer. Villus height and crypt depth increased 60% and 40% respectively, but by only 20% in fibre-free diabetic rats. The plasma levels of GLP-2 parallelled diabetic intestinal growth, whereas plasma levels of enteroglucagon increased regardless of the extent of intestinal growth. CONCLUSIONS—Intestinal growth in experimental diabetes is strongly influenced by the presence of dietary fibre. The effect may be mediated by GLP-2. Keywords: small intestine; intestinal adaptation; growth factors; dietary fibre; diabetes mellitus; rat

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (115.1 KB).

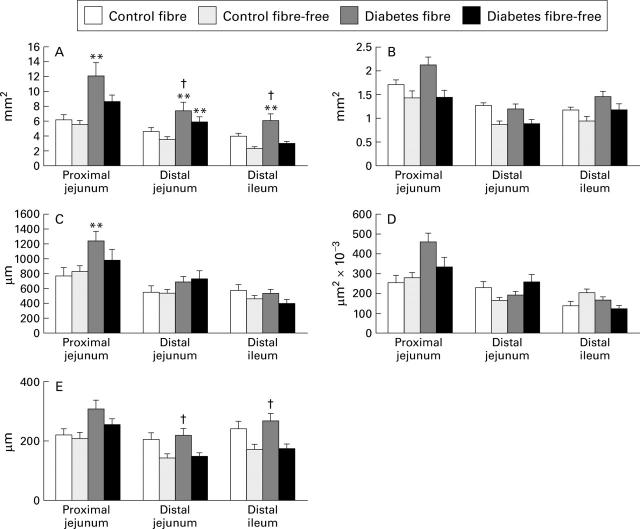

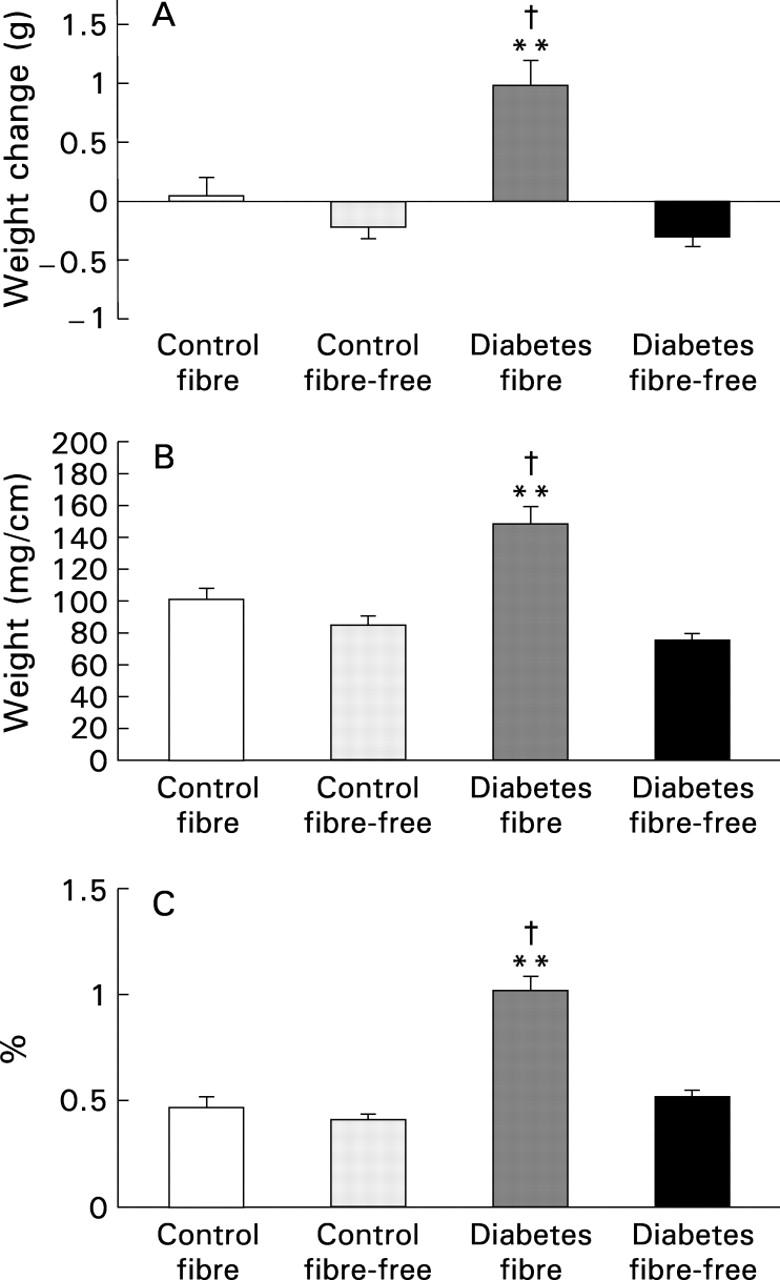

Figure 1 .

Weight of the small intestine in control and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet. (A) Mean weight change during the three weeks of the study; (B) weight per cm intestinal tissue; (C) intestinal tissue weight relative to final body weight. Data are expressed as mean (SEM). **p<0.01 v respective controls; †p<0.01 v diabetes fibre-free.

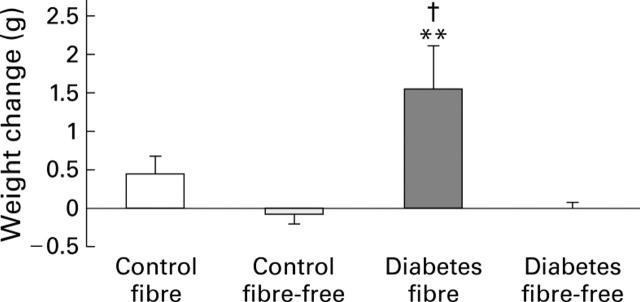

Figure 2 .

Morphometric estimates of the small intestine in control and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet. (A) Cross sectional area of the mucosal layer; (B) cross sectional area of the muscle layer; (C) villus height; (D) villus surface area; (E) crypt depth. Data are expressed as mean (SEM). **p<0.01 v respective controls; †p<0.01 v diabetes fibre-free. Villus height (C) and crypt depth (E) were increased about 60% and 40% respectively in the proximal jejunum of the diabetic rats fed the fibre-containing diet compared with controls. The average area of the villi (D) tended to be increased in the proximal jejunum. Villus height (C), villus area (D), and crypt depth (E) were similar in all three intestinal parts examined in the two control groups and the diabetic group fed the fibre-free diet.

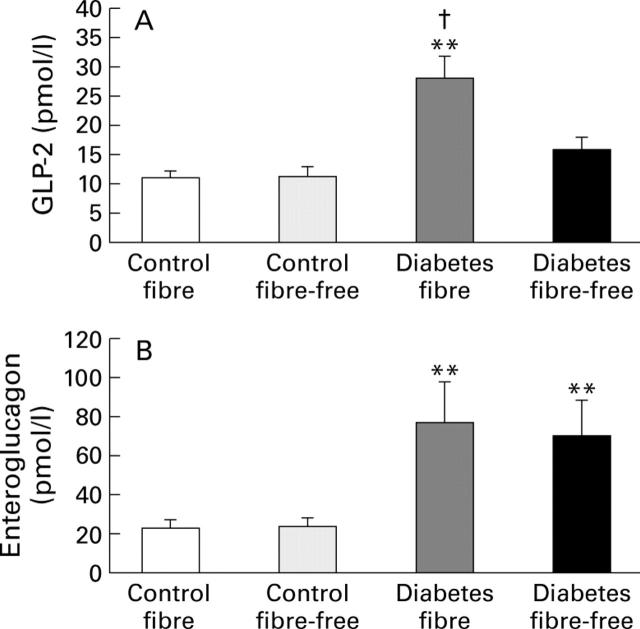

Figure 3 .

Mean change in caecum weight during the three weeks of study in control and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet. Data are expressed as mean (SEM). **p<0.01 v respective controls; †p<0.01 v diabetes fibre-free.

Figure 4 .

Weight of the large intestine in control and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet. (A) Mean weight change during the three weeks of the study; (B) weight per cm intestinal tissue; (C) intestinal tissue weight relative to final body weight. Data are expressed as mean (SEM). **p<0.01 v respective controls; †p<0.01 v diabetes fibre-free.

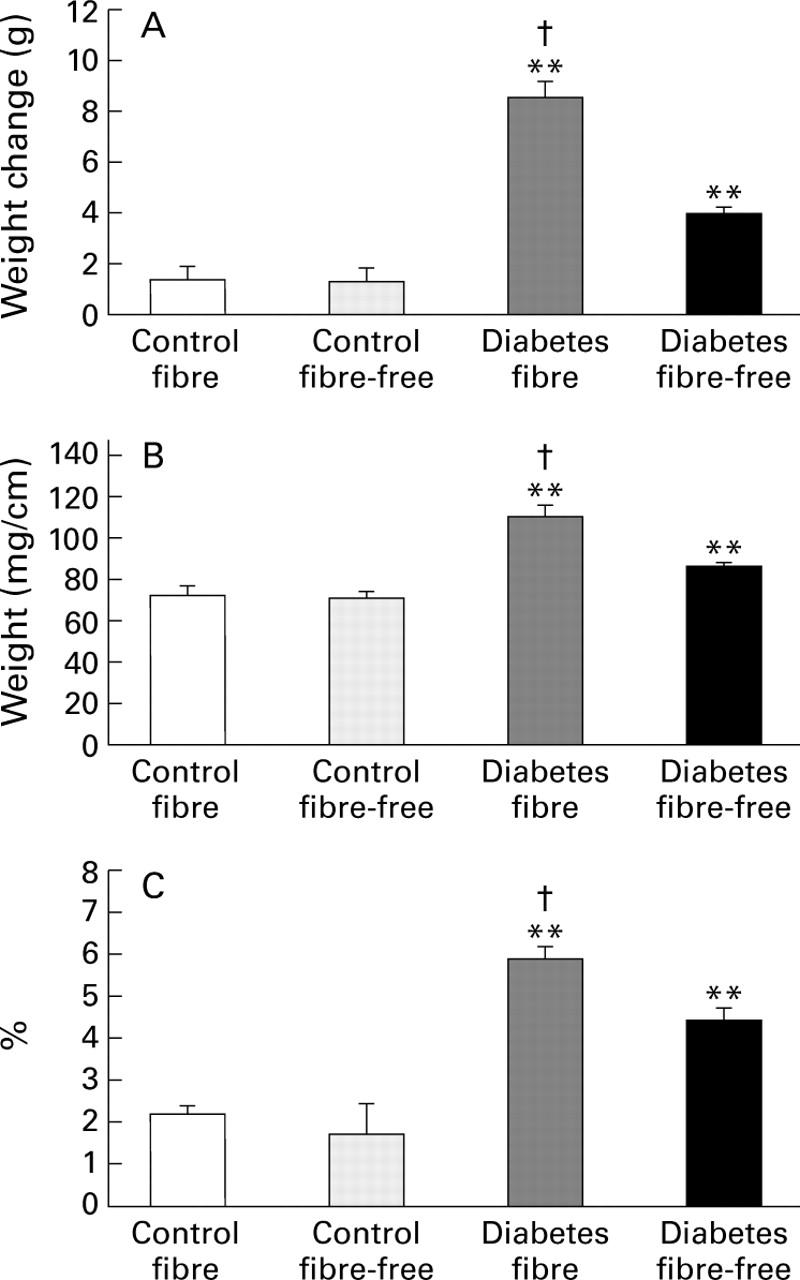

Figure 5 .

Plasma concentrations of the proglucagon derived peptides, GLP-2 and enteroglucagon (glicentin, oxyntomodulin), on day 13 in control and streptozotocin induced diabetic rats fed either a fibre-containing or a fibre-free diet. (A) Plasma concentrations of GLP-2; (B) plasma concentrations of enteroglucagon. Data are expressed as mean (SEM). **p<0.01 v respective controls; †p<0.01 v diabetes fibre-free.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Buhl T., Thim L., Kofod H., Orskov C., Harling H., Holst J. J. Naturally occurring products of proglucagon 111-160 in the porcine and human small intestine. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jun 25;263(18):8621–8624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy M. M., Lightfoot F. G., Grau L. E., Story J. A., Kritchevsky D., Vahouny G. V. Effect of chronic intake of dietary fibers on the ultrastructural topography of rat jejunum and colon: a scanning electron microscopy study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Feb;34(2):218–228. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chance W. T., Foley-Nelson T., Thomas I., Balasubramaniam A. Prevention of parenteral nutrition-induced gut hypoplasia by coinfusion of glucagon-like peptide-2. Am J Physiol. 1997 Aug;273(2 Pt 1):G559–G563. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.273.2.G559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke R. M. Progress in measuring epithelial turnover in the villus of the small intestine. Digestion. 1973;8(2):161–175. doi: 10.1159/000197311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H. Short chain fatty acids in the human colon. Gut. 1981 Sep;22(9):763–779. doi: 10.1136/gut.22.9.763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker D. J., Erlich P., Asa S. L., Brubaker P. L. Induction of intestinal epithelial proliferation by glucagon-like peptide 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Jul 23;93(15):7911–7916. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drucker D. J., Shi Q., Crivici A., Sumner-Smith M., Tavares W., Hill M., DeForest L., Cooper S., Brubaker P. L. Regulation of the biological activity of glucagon-like peptide 2 in vivo by dipeptidyl peptidase IV. Nat Biotechnol. 1997 Jul;15(7):673–677. doi: 10.1038/nbt0797-673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer K. D., Dhanvantari S., Drucker D. J., Brubaker P. L. Intestinal growth is associated with elevated levels of glucagon-like peptide 2 in diabetic rats. Am J Physiol. 1997 Oct;273(4 Pt 1):E815–E820. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.4.E815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel W. L., Zhang W., Singh A., Klurfeld D. M., Don S., Sakata T., Modlin I., Rombeau J. L. Mediation of the trophic effects of short-chain fatty acids on the rat jejunum and colon. Gastroenterology. 1994 Feb;106(2):375–380. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel W. L., Zhang W., Singh A., Klurfeld D. M., Don S., Sakata T., Modlin I., Rombeau J. L. Mediation of the trophic effects of short-chain fatty acids on the rat jejunum and colon. Gastroenterology. 1994 Feb;106(2):375–380. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller P. J., Beveridge D. J., Taylor R. G. Ileal proglucagon gene expression in the rat: characterization in intestinal adaptation using in situ hybridization. Gastroenterology. 1993 Feb;104(2):459–466. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee J. M., Lee-Finglas W., Wortley G. W., Johnson I. T. Fermentable carbohydrates elevate plasma enteroglucagon but high viscosity is also necessary to stimulate small bowel mucosal cell proliferation in rats. J Nutr. 1996 Feb;126(2):373–379. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.2.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghatei M. A., Ratcliffe B., Bloom S. R., Goodlad R. A. Fermentable dietary fibre, intestinal microflora and plasma hormones in the rat. Clin Sci (Lond) 1997 Aug;93(2):109–112. doi: 10.1042/cs0930109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad R. A., Lenton W., Ghatei M. A., Adrian T. E., Bloom S. R., Wright N. A. Effects of an elemental diet, inert bulk and different types of dietary fibre on the response of the intestinal epithelium to refeeding in the rat and relationship to plasma gastrin, enteroglucagon, and PYY concentrations. Gut. 1987 Feb;28(2):171–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.28.2.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad R. A., Ratcliffe B., Fordham J. P., Wright N. A. Does dietary fibre stimulate intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in germ free rats? Gut. 1989 Jun;30(6):820–825. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad R. A., Wright N. A. Effects of addition of kaolin or cellulose to an elemental diet on intestinal cell proliferation in the mouse. Br J Nutr. 1983 Jul;50(1):91–98. doi: 10.1079/bjn19830075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregor M., Stallmach A., Menge H., Riecken E. O. The role of gut-glucagon-like immunoreactants in the control of gastrointestinal epithelial cell renewal. Digestion. 1990;46 (Suppl 2):59–65. doi: 10.1159/000200368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez L., Briese E. Analysis of diabetic hyperphagia and polydipsia. Physiol Behav. 1972 Nov-Dec;9(5):741–746. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(72)90044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J. J. Enteroglucagon. Annu Rev Physiol. 1997;59:257–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J. J. Evidence that enteroglucagon (II) is identical with the C-terminal sequence (residues 33-69) of glicentin. Biochem J. 1982 Dec 1;207(3):381–388. doi: 10.1042/bj2070381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holst J. J. Evidence that glicentin contains the entire sequence of glucagon. Biochem J. 1980 May 1;187(2):337–343. doi: 10.1042/bj1870337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins A. P., Thompson R. P. Enteral nutrition and the small intestine. Gut. 1994 Dec;35(12):1765–1769. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.12.1765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jervis E. L., Levin R. J. Anatomic adaptation of the alimentary tract of the rat to the hyperphagia of chronic alloxan-diabetes. Nature. 1966 Apr 23;210(5034):391–393. doi: 10.1038/210391a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson I. T., Gee J. M., Brown J. C. Plasma enteroglucagon and small bowel cytokinetics in rats fed soluble nonstarch polysaccharides. Am J Clin Nutr. 1988 Jun;47(6):1004–1009. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/47.6.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koruda M. J., Rolandelli R. H., Bliss D. Z., Hastings J., Rombeau J. L., Settle R. G. Parenteral nutrition supplemented with short-chain fatty acids: effect on the small-bowel mucosa in normal rats. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990 Apr;51(4):685–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koruda M. J., Rolandelli R. H., Bliss D. Z., Hastings J., Rombeau J. L., Settle R. G. Parenteral nutrition supplemented with short-chain fatty acids: effect on the small-bowel mucosa in normal rats. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990 Apr;51(4):685–689. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.4.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kripke S. A., Fox A. D., Berman J. M., Settle R. G., Rombeau J. L. Stimulation of intestinal mucosal growth with intracolonic infusion of short-chain fatty acids. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1989 Mar-Apr;13(2):109–116. doi: 10.1177/0148607189013002109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYER J. Genetic, traumatic and environmental factors in the etiology of obesity. Physiol Rev. 1953 Oct;33(4):472–508. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1953.33.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miazza B. M., Al-Mukhtar M. Y., Salmeron M., Ghatei M. A., Felce-Dachez M., Filali A., Villet R., Wright N. A., Bloom S. R., Crambaud J. C. Hyperenteroglucagonaemia and small intestinal mucosal growth after colonic perfusion of glucose in rats. Gut. 1985 May;26(5):518–524. doi: 10.1136/gut.26.5.518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin C. L., Ling V., Bourassa D. Small intestinal and colonic changes induced by a chemically defined diet. Dig Dis Sci. 1980 Feb;25(2):123–128. doi: 10.1007/BF01308310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyman M., Asp N. G. Fermentation of dietary fibre components in the rat intestinal tract. Br J Nutr. 1982 May;47(3):357–366. doi: 10.1079/bjn19820047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orskov C., Holst J. J., Knuhtsen S., Baldissera F. G., Poulsen S. S., Nielsen O. V. Glucagon-like peptides GLP-1 and GLP-2, predicted products of the glucagon gene, are secreted separately from pig small intestine but not pancreas. Endocrinology. 1986 Oct;119(4):1467–1475. doi: 10.1210/endo-119-4-1467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimer R. A., McBurney M. I. Dietary fiber modulates intestinal proglucagon messenger ribonucleic acid and postprandial secretion of glucagon-like peptide-1 and insulin in rats. Endocrinology. 1996 Sep;137(9):3948–3956. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberge J. N., Brubaker P. L. Secretion of proglucagon-derived peptides in response to intestinal luminal nutrients. Endocrinology. 1991 Jun;128(6):3169–3174. doi: 10.1210/endo-128-6-3169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roediger W. E. Utilization of nutrients by isolated epithelial cells of the rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1982 Aug;83(2):424–429. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagor G. R., Al-Mukhtar M. Y., Ghatei M. A., Wright N. A., Bloom S. R. The effect of altered luminal nutrition on cellular proliferation and plasma concentrations of enteroglucagon and gastrin after small bowel resection in the rat. Br J Surg. 1982 Jan;69(1):14–18. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800690106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T. Stimulatory effect of short-chain fatty acids on epithelial cell proliferation in the rat intestine: a possible explanation for trophic effects of fermentable fibre, gut microbes and luminal trophic factors. Br J Nutr. 1987 Jul;58(1):95–103. doi: 10.1079/bjn19870073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T. Stimulatory effect of short-chain fatty acids on epithelial cell proliferation of isolated and denervated jejunal segment of the rat. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989 Sep;24(7):886–890. doi: 10.3109/00365528909089230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T., Yajima T. Influence of short chain fatty acids on the epithelial cell division of digestive tract. Q J Exp Physiol. 1984 Jul;69(3):639–648. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1984.sp002850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedl H. P., Wilson H. D. Effects of diabetes on intestinal growth in the rat. J Exp Zool. 1971 Apr;176(4):487–495. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401760410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott R. B., Kirk D., MacNaughton W. K., Meddings J. B. GLP-2 augments the adaptive response to massive intestinal resection in rat. Am J Physiol. 1998 Nov;275(5 Pt 1):G911–G921. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.275.5.G911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka R., Matsuyama T., Shima K., Sawazaki N., Tarui S., Kumahara Y. Half life of gastrointestinal glucagon-like immunoreactive materials. Endocrinol Jpn. 1979 Feb;26(1):59–63. doi: 10.1507/endocrj1954.26.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tappenden K. A., McBurney M. I. Systemic short-chain fatty acids rapidly alter gastrointestinal structure, function, and expression of early response genes. Dig Dis Sci. 1998 Jul;43(7):1526–1536. doi: 10.1023/a:1018819032620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thulesen J., Orskov C., Holst J. J., Poulsen S. S. Short-term insulin treatment prevents the diabetogenic action of streptozotocin in rats. Endocrinology. 1997 Jan;138(1):62–68. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.1.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. H., Hill M., Asa S. L., Brubaker P. L., Drucker D. J. Intestinal growth-promoting properties of glucagon-like peptide-2 in mice. Am J Physiol. 1997 Jul;273(1 Pt 1):E77–E84. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1997.273.1.E77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai C. H., Hill M., Drucker D. J. Biological determinants of intestinotrophic properties of GLP-2 in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1997 Mar;272(3 Pt 1):G662–G668. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.3.G662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uribe A., Alam M., Johansson O., Midtvedt T., Theodorsson E. Microflora modulates endocrine cells in the gastrointestinal mucosa of the rat. Gastroenterology. 1994 Nov;107(5):1259–1269. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90526-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varndell I. M., Bishop A. E., Sikri K. L., Uttenthal L. O., Bloom S. R., Polak J. M. Localization of glucagon-like peptide (GLP) immunoreactants in human gut and pancreas using light and electron microscopic immunocytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985 Oct;33(10):1080–1086. doi: 10.1177/33.10.3900195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R. C., Buchholtz T. W., Malt R. A. Humoral stimulation of cell proliferation in small bowel after transection and resection in rats. Gastroenterology. 1978 Aug;75(2):249–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wøjdemann M., Wettergren A., Hartmann B., Holst J. J. Glucagon-like peptide-2 inhibits centrally induced antral motility in pigs. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1998 Aug;33(8):828–832. doi: 10.1080/00365529850171486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]