Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS—The mechanism of intraduodenal fat induced inhibition of food intake is still unclear. Therefore, we tested the ability of duodenal fatty acids to suppress food intake at a lunchtime meal; in addition, we were interested to test if these effects were mediated by cholecystokinin (CCK) A receptors. SUBJECTS AND METHODS—Three sequential double blind, three period crossover studies were performed in 12 healthy males each: (1) subjects received intraduodenal fat with or without 120 mg of tetrahydrolipstatin, an inhibitor of gastrointestinal lipases, or saline; (2) volunteers received intraduodenal long chain fatty acids, medium chain fatty acids, or saline; (3) subjects received long chain fatty acids or saline together with concomitant intravenous infusions of saline or loxiglumide, a specific CCK-A receptor antagonist. The effect of these treatments on food intake and feelings of hunger was quantified. RESULTS—Intraduodenal fat perfusion significantly (p<0.05) reduced calorie intake. Inhibition of fat hydrolysis abolished this effect. Only long chain fatty acids significantly (p<0.05) decreased calorie intake, whereas medium chain fatty acids were ineffective. Infusion of loxiglumide abolished the effect of long chain fatty acids. CONCLUSIONS—Generation of long chain fatty acids through hydrolysis of fat is a critical step for fat induced inhibition of food intake; the signal is mediated via CCK-A receptors. Keywords: food intake; long chain fatty acids; medium chain fatty acids; cholecystokinin

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (144.8 KB).

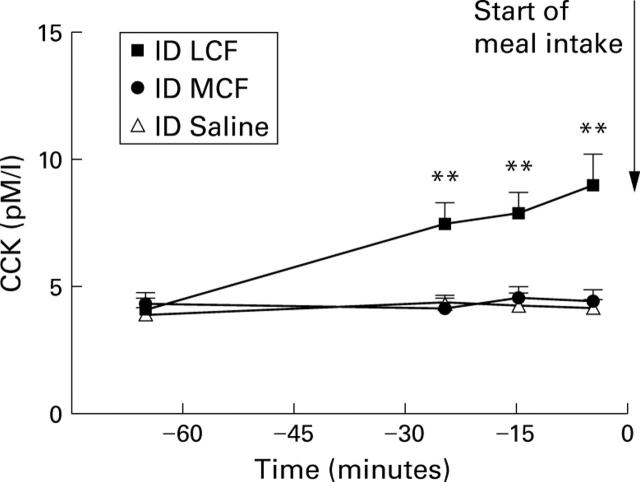

Figure 1 .

Plasma cholecystokinin (CCK) concentrations in the pre-meal period during intraduodenal (ID) perfusions of MCF, LCF, or saline in 12 healthy male subjects. Data are mean (SEM). **Significant increase in plasma CCK levels during LCF perfusion compared with saline (p<0.01).

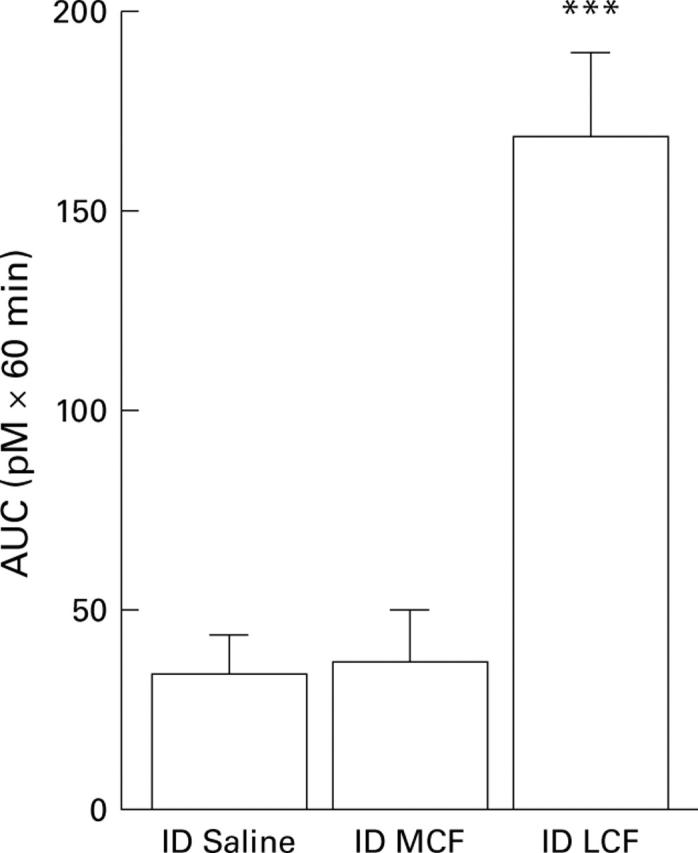

Figure 2 .

AUC of plasma cholecystokinin (CCK) responses to intraduodenal (ID) perfusion of saline, MCF, or LCF during the pre-meal period in 12 healthy male subjects. Results are mean (SEM). ***Significant difference between ID LCF v ID saline administration (AUC: p⩽0.0001).

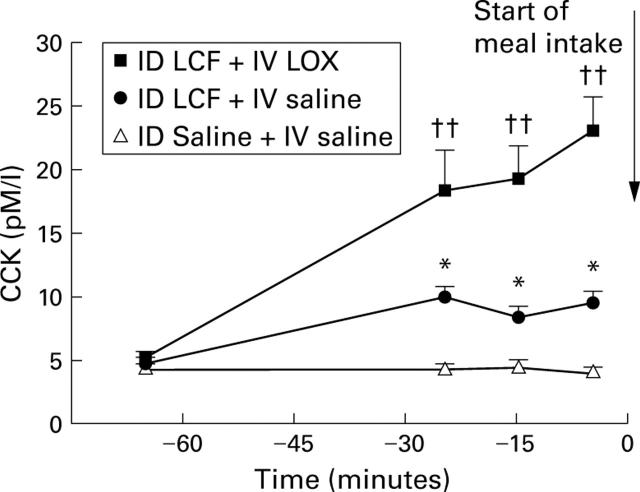

Figure 3 .

Plasma cholecystokinin (CCK) concentrations in the pre-meal period during intraduodenal (ID) perfusion of LCF with intravenous (IV) saline, ID LCF with IV LOX, or ID saline with IV saline in 12 healthy male subjects. Data are mean (SEM). *Significant increase in plasma CCK between ID LCF + IV saline v ID saline + IV saline (p<0.05); ††significant increase in plasma CCK levels between ID saline + IV saline v ID LCF + IV LOX (p<0.01).

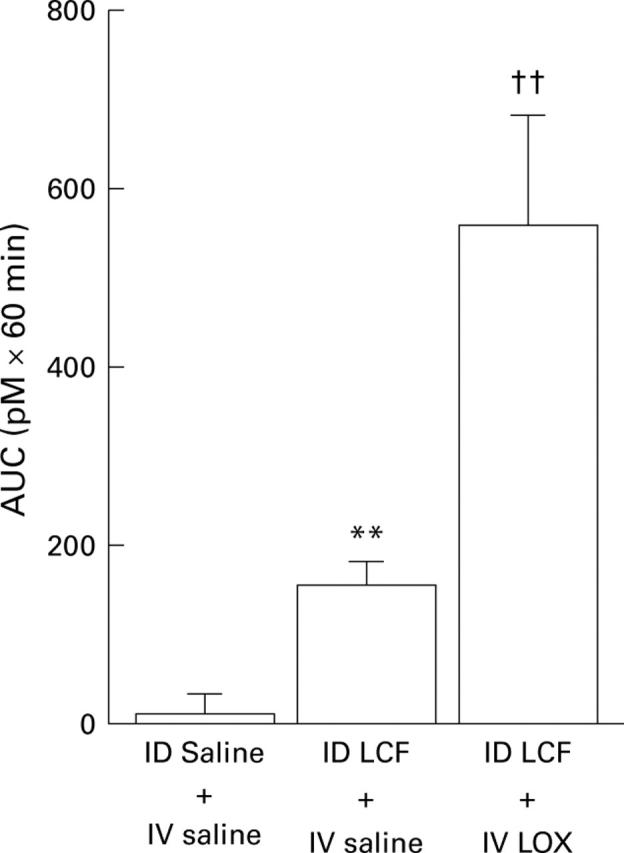

Figure 4 .

AUC of plasma cholecystokinin (CCK) responses to intraduodenal (ID) perfusion of saline with intravenous (IV) infusion of saline, ID LCF with IV saline, or ID LCF with IV LOX during the pre-meal period in 12 healthy male subjects . Results are mean (SEM). **Significant difference between ID saline + IV saline v ID LCF + IV saline (AUC: p<0.01); ††significant difference between ID saline + IV saline v ID LCF + IV LOX (AUC: p<0.005).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bado A., Levasseur S., Attoub S., Kermorgant S., Laigneau J. P., Bortoluzzi M. N., Moizo L., Lehy T., Guerre-Millo M., Le Marchand-Brustel Y. The stomach is a source of leptin. Nature. 1998 Aug 20;394(6695):790–793. doi: 10.1038/29547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrachina M. D., Martínez V., Wang L., Wei J. Y., Taché Y. Synergistic interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin to reduce short-term food intake in lean mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997 Sep 16;94(19):10455–10460. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.19.10455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgström B. Mode of action of tetrahydrolipstatin: a derivative of the naturally occurring lipase inhibitor lipstatin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988 Oct 14;962(3):308–316. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(88)90260-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. B., Brause B., Holt P. R. Lipolysis and absorption of fat in the rat stomach. Gastroenterology. 1969 Feb;56(2):214–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demol P., Sarles H. Action of fatty acids on the exocrine pancreatic secretion of the conscious rat: further evidence for a protein pancreatic inhibitory factor. J Physiol. 1978 Feb;275:27–37. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewe J., Gadient A., Rovati L. C., Beglinger C. Role of circulating cholecystokinin in control of fat-induced inhibition of food intake in humans. Gastroenterology. 1992 May;102(5):1654–1659. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91726-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlewicz D. P., Sipols A. J., Porte D., Jr, Woods S. C., Liddle R. A. Intraventricular CCK inhibits food intake and gastric emptying in baboons. Am J Physiol. 1989 Jun;256(6 Pt 2):R1313–R1317. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1989.256.6.R1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foltin R. W., Moran T. H. Food intake in baboons: effects of a long-acting cholecystokinin analog. Appetite. 1989 Apr;12(2):145–152. doi: 10.1016/0195-6663(89)90103-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Falasco J. D., McHugh P. R. Cholecystokinin-decreased food intake in rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol. 1976 Jan;230(1):15–18. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1976.230.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs J., Young R. C., Smith G. P. Cholecystokinin elicits satiety in rats with open gastric fistulas. Nature. 1973 Oct 12;245(5424):323–325. doi: 10.1038/245323a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D., Kava R. A., Lewis D. R., Greenwood M. R., Smith G. P. Time course for entry of intestinally infused lipids into blood of rats. Am J Physiol. 1995 Aug;269(2 Pt 2):R432–R436. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.2.R432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D., Smith G. P., Gibbs J. Intraduodenal infusions of fats elicit satiety in sham-feeding rats. Am J Physiol. 1990 Jul;259(1 Pt 2):R110–R118. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1990.259.1.R110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg D., Smith G. P., Gibbs J. Intravenous triglycerides fail to elicit satiety in sham-feeding rats. Am J Physiol. 1993 Feb;264(2 Pt 2):R409–R413. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1993.264.2.R409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory P. C., Rayner D. V. The influence of gastrointestinal infusion of fats on regulation of food intake in pigs. J Physiol. 1987 Apr;385:471–481. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadváry P., Lengsfeld H., Wolfer H. Inhibition of pancreatic lipase in vitro by the covalent inhibitor tetrahydrolipstatin. Biochem J. 1988 Dec 1;256(2):357–361. doi: 10.1042/bj2560357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimura E., Shimizu F., Nishino T., Imagawa K., Tateishi K., Hamaoka T. Production of rabbit antibody specific for amino-terminal residues of cholecystokinin octapeptide (CCK-8) by selective suppression of cross-reactive antibody response. J Immunol Methods. 1982 Dec 30;55(3):375–387. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(82)90097-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernell O., Staggers J. E., Carey M. C. Physical-chemical behavior of dietary and biliary lipids during intestinal digestion and absorption. 2. Phase analysis and aggregation states of luminal lipids during duodenal fat digestion in healthy adult human beings. Biochemistry. 1990 Feb 27;29(8):2041–2056. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand P., Petrig C., Burckhardt B., Ketterer S., Lengsfeld H., Fleury A., Hadváry P., Beglinger C. Hydrolysis of dietary fat by pancreatic lipase stimulates cholecystokinin release. Gastroenterology. 1998 Jan;114(1):123–129. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopman W. P., Jansen J. B., Rosenbusch G., Lamers C. B. Effect of equimolar amounts of long-chain triglycerides and medium-chain triglycerides on plasma cholecystokinin and gallbladder contraction. Am J Clin Nutr. 1984 Mar;39(3):356–359. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/39.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacs P. E., Ladas S., Forgacs I. C., Dowling R. H., Ellam S. V., Adrian T. E., Bloom S. R. Comparison of effects of ingested medium- and long-chain triglyceride on gallbladder volume and release of cholecystokinin and other gut peptides. Dig Dis Sci. 1987 May;32(5):481–486. doi: 10.1007/BF01296030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kissileff H. R., Pi-Sunyer F. X., Thornton J., Smith G. P. C-terminal octapeptide of cholecystokinin decreases food intake in man. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981 Feb;34(2):154–160. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/34.2.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieverse R. J., Jansen J. B., Masclee A. A., Rovati L. C., Lamers C. B. Effect of a low dose of intraduodenal fat on satiety in humans: studies using the type A cholecystokinin receptor antagonist loxiglumide. Gut. 1994 Apr;35(4):501–505. doi: 10.1136/gut.35.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin J., Grazia Lucà M., Jones M. N., D'Amato M., Dockray G. J., Thompson D. G. Fatty acid chain length determines cholecystokinin secretion and effect on human gastric motility. Gastroenterology. 1999 Jan;116(1):46–53. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier R., Hildebrand P., Thumshirn M., Albrecht C., Studer B., Gyr K., Beglinger C. Effect of loxiglumide, a cholecystokinin antagonist, on pancreatic polypeptide release in humans. Gastroenterology. 1990 Dec;99(6):1757–1762. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90484-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer J. H., Jones R. S. Canine pancreatic responses to intestinally perfused fat and products of fat digestion. Am J Physiol. 1974 May;226(5):1178–1187. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1974.226.5.1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller L. J., Malagelada J. R., Taylor W. F., Go V. L. Intestinal control of human postprandial gastric function: the role of components of jejunoileal chyme in regulating gastric secretion and gastric emptying. Gastroenterology. 1981 Apr;80(4):763–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran T. H., Smith G. P., Hostetler A. M., McHugh P. R. Transport of cholecystokinin (CCK) binding sites in subdiaphragmatic vagal branches. Brain Res. 1987 Jul 7;415(1):149–152. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)90278-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholl C. G., Polak J. M., Bloom S. R. The hormonal regulation of food intake, digestion, and absorption. Annu Rev Nutr. 1985;5:213–239. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.05.070185.001241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read N. W., McFarlane A., Kinsman R. I., Bates T. E., Blackhall N. W., Farrar G. B., Hall J. C., Moss G., Morris A. P., O'Neill B. Effect of infusion of nutrient solutions into the ileum on gastrointestinal transit and plasma levels of neurotensin and enteroglucagon. Gastroenterology. 1984 Feb;86(2):274–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SENIOR J. R. INTESTINAL ABSORPTION OF FATS. J Lipid Res. 1964 Oct;5:495–521. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spannagel A. W., Nakano I., Tawil T., Chey W. Y., Liddle R. A., Green G. M. Adaptation to fat markedly increases pancreatic secretory response to intraduodenal fat in rats. Am J Physiol. 1996 Jan;270(1 Pt 1):G128–G135. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1996.270.1.G128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staggers J. E., Hernell O., Stafford R. J., Carey M. C. Physical-chemical behavior of dietary and biliary lipids during intestinal digestion and absorption. 1. Phase behavior and aggregation states of model lipid systems patterned after aqueous duodenal contents of healthy adult human beings. Biochemistry. 1990 Feb 27;29(8):2028–2040. doi: 10.1021/bi00460a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherford S. C., Chiruzzo F. Y., Laughton W. B. Satiety induced by endogenous and exogenous cholecystokinin is mediated by CCK-A receptors in mice. Am J Physiol. 1992 Apr;262(4 Pt 2):R574–R578. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1992.262.4.R574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch I. M., Sepple C. P., Read N. W. Comparisons of the effects on satiety and eating behaviour of infusion of lipid into the different regions of the small intestine. Gut. 1988 Mar;29(3):306–311. doi: 10.1136/gut.29.3.306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch I., Saunders K., Read N. W. Effect of ileal and intravenous infusions of fat emulsions on feeding and satiety in human volunteers. Gastroenterology. 1985 Dec;89(6):1293–1297. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(85)90645-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woltman T., Castellanos D., Reidelberger R. Role of cholecystokinin in the anorexia produced by duodenal delivery of oleic acid in rats. Am J Physiol. 1995 Dec;269(6 Pt 2):R1420–R1433. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1995.269.6.R1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yox D. P., Stokesberry H., Ritter R. C. Fourth ventricular capsaicin attenuates suppression of sham feeding induced by intestinal nutrients. Am J Physiol. 1991 Apr;260(4 Pt 2):R681–R687. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.4.R681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yox D. P., Stokesberry H., Ritter R. C. Vagotomy attenuates suppression of sham feeding induced by intestinal nutrients. Am J Physiol. 1991 Mar;260(3 Pt 2):R503–R508. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1991.260.3.R503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]