Abstract

BACKGROUND/AIMS—Alterations in synthesis and breakdown of extracellular matrix components are known to play a crucial role in tissue remodelling during inflammation and wound healing. Degradation of collagens is highly regulated by a cascade of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs). The current study was therefore designed to determine gene expression patterns of MMPs and their tissue inhibitors (TIMPs) in single endoscopic biopsies of patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). PATIENTS/METHODS—mRNA expression was measured by quantitative competitive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in biopsies from patients with ulcerative colitis (n=21) and Crohn's disease (n=21). Protein expression was analysed by western blotting and immunohistochemistry. RESULTS—MMP-2, MMP-14, and TIMP-1 mRNAs were marginally increased in inflamed, but 9-12-fold increased in ulcerated colonic mucosa in IBD whereas TIMP-2 mRNA expression remained unchanged. MMP-1 and MMP-3 mRNA expression correlated well with the histological degree of acute inflammation, resulting in more than 15-fold increased MMP-1 and MMP-3 mRNA levels in inflamed versus normal colon samples from patients with ulcerative colitis and Crohn's disease. CONCLUSION—Profound overexpression of MMP-1 and MMP-3 mRNA transcripts suggests an important role for these enzymes in the process of tissue remodelling and destruction in inflammatory bowel disease. Keywords: matrix metalloproteinases; polymerase chain reaction; extracellular matrix; Crohn's disease; ulcerative colitis.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (302.2 KB).

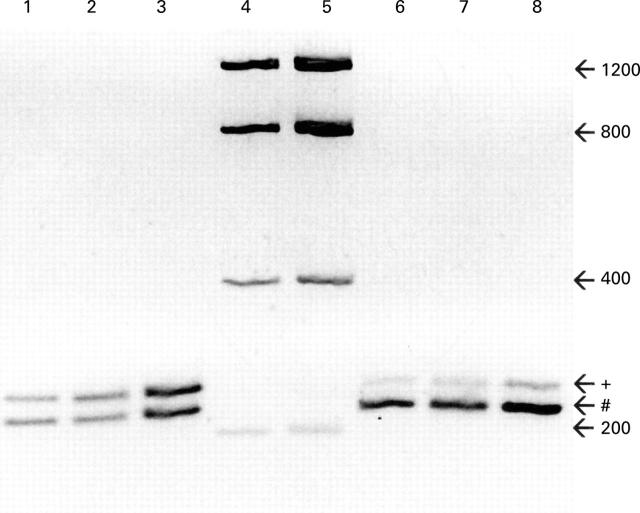

Figure 1 .

Evaluation of equal amplification efficiencies of the MMP-1 PCR product and the MMP-1 competitor construct. Purified MMP-1 PCR product (+; 247 bp) and the MMP-1 competitor construct (#; 222 bp) were mixed in an OD ratio of 1:1 (lane 1) and 1:5 (lane 6). These solutions were diluted 1:200 000 and used as templates for PCR for 27 cycles (lanes 2, 7) and 35 cycles (lanes 3, 8). An inverted image of an ethidium bromide stained gel is shown demonstrating equal density ratios before (lanes 1, 6) and after (lanes 2, 3, 7, 8) reamplification. Lanes 4 and 5 contain a DNA mass standard used for calibration of the densitometry. Numbers on the right indicate the DNA size in base pairs (bp).

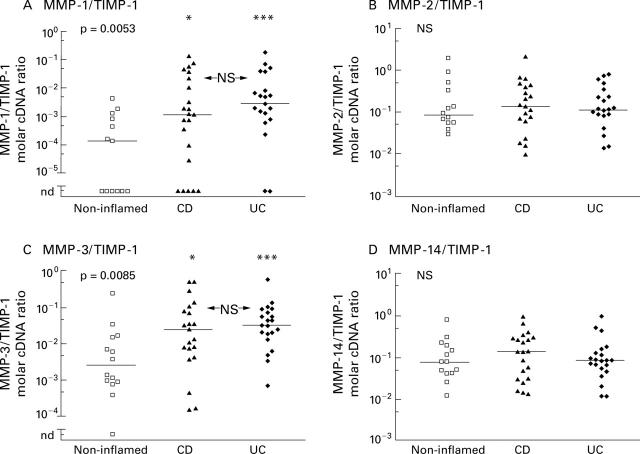

Figure 2 .

Expression of MMP-1, -2, -3, -14, the tissue inhibitors TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, collagen type III, and GAPDH mRNA in colon biopsies from non-inflamed areas and inflamed areas of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Expression was measured by a competitive PCR technique and is expressed as the molar ratio of gene specific to β-actin copies. Scattergrams of all measurements in a logarithmic scale are shown. Bars represents the medians of the groups. Degree of statistical significance calculated by the Kruskal-Wallis test is given in each upper left corner. Statistically significant differences between the three groups (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; NS, not significant) were calculated using Dunn's post hoc test.

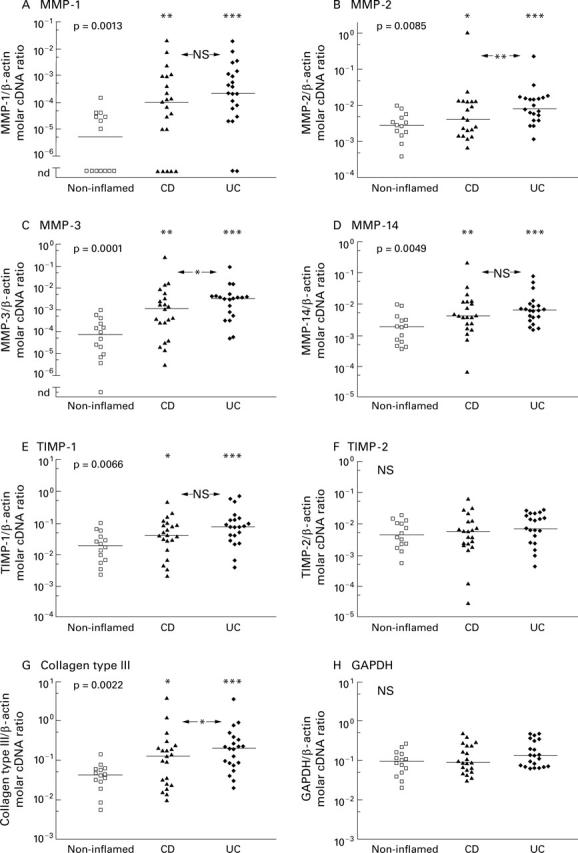

Figure 3 .

Increased protein expression of MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-3 in inflamed (i) versus non-inflamed (n) colon biopsies from patients with IBD. Endoscopic biopsies from macro- and microscopically normal (lanes 1, 3, 5) and inflamed (lanes 2, 4, 6) colon of one patient with Crohn's disease (lanes 1, 2) and two patients with ulcerative colitis (lanes 3-6) were lysed in a buffer containing a cocktail of protease inhibitors. Proteins were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to PVDF membranes. Membranes were probed with antibodies against MMP-1 (A), MMP-2 (B), and MMP-3 (C) and bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence. Membranes were reprobed with an antibody against β-actin (D) as a loading control. Estimated molecular weights of the bands detected are given on the right.

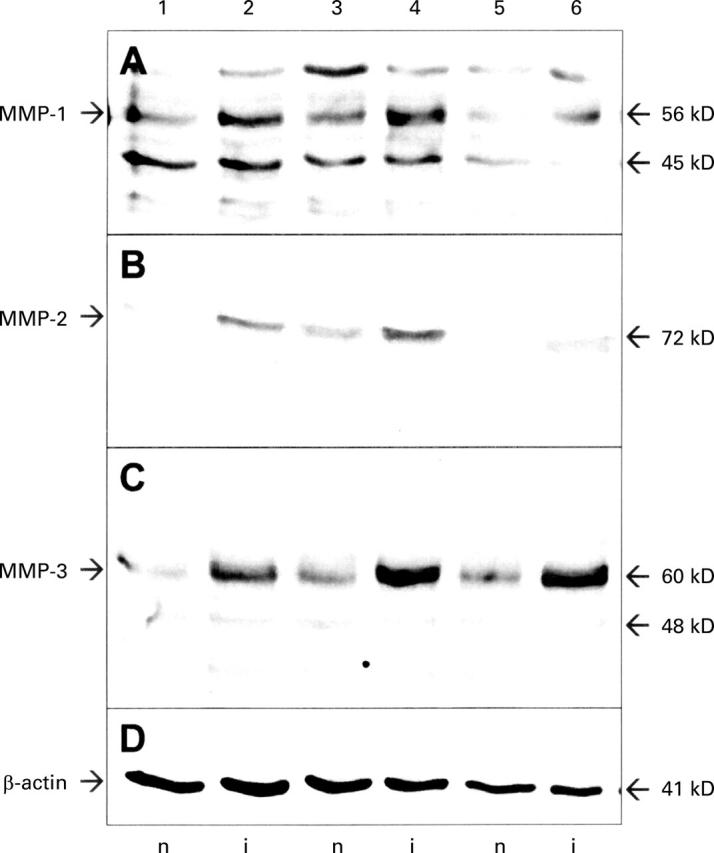

Figure 4 .

Molar ratios of matrix metalloproteinase to TIMP-1 specific cDNA derived from reverse transcribed mRNA isolated from colon biopsies of non-inflamed areas and inflamed areas of patients with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Competitive PCR measurements are displayed as scattergrams in a logarithmic scale. Bars represent the medians of the groups. Statistical significance, calculated using the Kruskal-Wallis test, is given in each upper left corner. Statistically significant differences between the three groups (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001; NS, not significant) were calculated using Dunn's post hoc test.

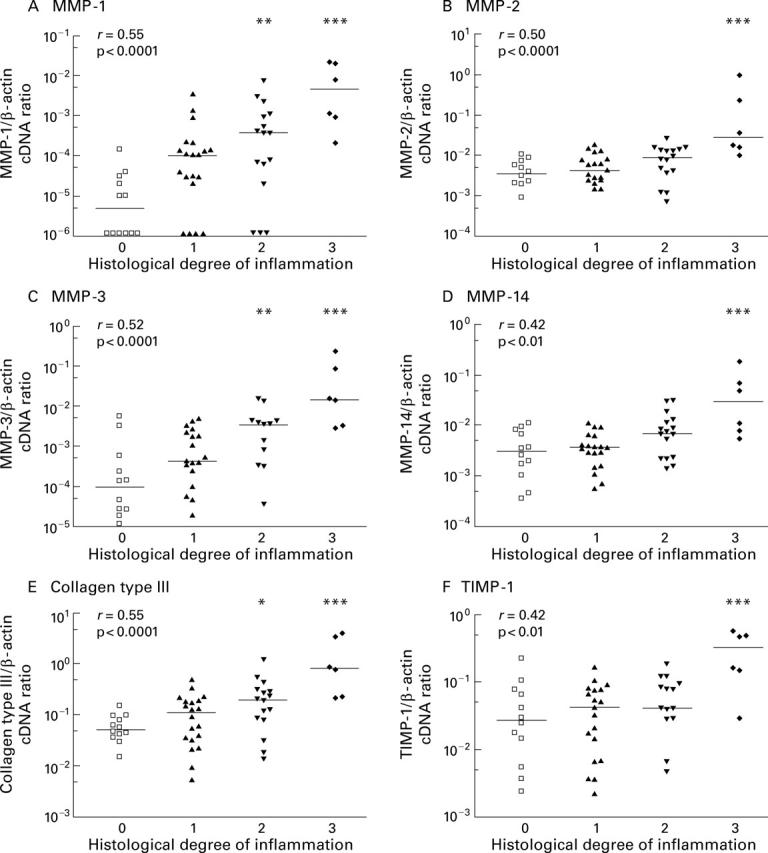

Figure 5 .

Relationship between histological degree of acute inflammation in colon biopsies from IBD patients and mRNA expression of MMPs, TIMP-1, and collagen type III measured by competitive PCR. Scattergrams show the ratio of gene specific transcripts to β-actin transcripts in a logarithmic scale and bars mark the medians of each group. The histological degree of acute inflammation was graded according to Truelove and Richards on a four point scale: no (0), mild (1), moderate (2), and severe (3) inflammation, as outlined in the methods section. Correlation between histological score and mRNA expression was computed using the Spearman rank test and the correlation coefficient r is given in the upper left corner. Statistical significant differences between probes with and without histological confirmed acute inflammation were calculated (*p<0.05, **p<0.01,***p<0.001).

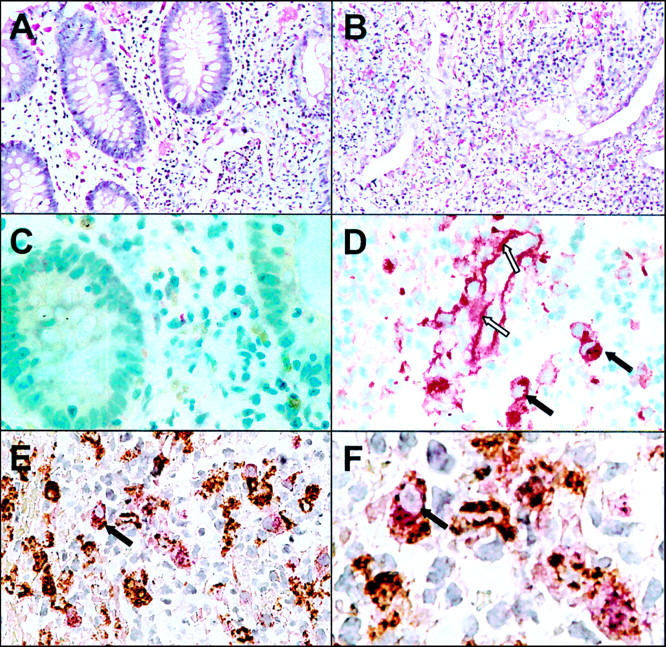

Figure 6 .

Immunohistochemical staining of MMP-1 in inflamed and non-inflamed colon of a patient with ulcerative colitis. Section of paraffin embedded biopsies from non-inflamed (A, C) and inflamed (B, D-F) colon were stained with haematoxylin/eosin (A, B) and anti-MMP-1 polyclonal antibody using the APAAP technique (C, D). Double immunostaining with anti-MMP-1 (stained red) and anti-CD68 (stained brown) is shown in (E) and a magnified view is given in (F). Dark arrows indicate macrophages expressing CD68 and MMP-1; open arrows indicate extracellular MMP-1 staining along the basal membrane of a blood vessel.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander-Williams J. Surgical aspects of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol Suppl. 1990;172:39–42. doi: 10.3109/00365529009091908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur M. J. Fibrosis and altered matrix degradation. Digestion. 1998 Jul-Aug;59(4):376–380. doi: 10.1159/000007492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey C. J., Hembry R. M., Alexander A., Irving M. H., Grant M. E., Shuttleworth C. A. Distribution of the matrix metalloproteinases stromelysin, gelatinases A and B, and collagenase in Crohn's disease and normal intestine. J Clin Pathol. 1994 Feb;47(2):113–116. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baragi V. M., Qiu L., Gunja-Smith Z., Woessner J. F., Jr, Lesch C. A., Guglietta A. Role of metalloproteinases in the development and healing of acetic acid-induced gastric ulcer in rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1997 May;32(5):419–426. doi: 10.3109/00365529709025075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown P. D. Matrix metalloproteinases in gastrointestinal cancer. Gut. 1998 Aug;43(2):161–163. doi: 10.1136/gut.43.2.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordell J. L., Falini B., Erber W. N., Ghosh A. K., Abdulaziz Z., MacDonald S., Pulford K. A., Stein H., Mason D. Y. Immunoenzymatic labeling of monoclonal antibodies using immune complexes of alkaline phosphatase and monoclonal anti-alkaline phosphatase (APAAP complexes). J Histochem Cytochem. 1984 Feb;32(2):219–229. doi: 10.1177/32.2.6198355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daum S., Bauer U., Foss H. D., Schuppan D., Stein H., Riecken E. O., Ullrich R. Increased expression of mRNA for matrix metalloproteinases-1 and -3 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 in intestinal biopsy specimens from patients with coeliac disease. Gut. 1999 Jan;44(1):17–25. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.1.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeClerck Y. A., Yean T. D., Lu H. S., Ting J., Langley K. E. Inhibition of autoproteolytic activation of interstitial procollagenase by recombinant metalloproteinase inhibitor MI/TIMP-2. J Biol Chem. 1991 Feb 25;266(6):3893–3899. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsmore S. E., Saarialho-Kere U. K., Roby J. D., Wilson C. L., Matrisian L. M., Welgus H. G., Parks W. C. Matrilysin expression and function in airway epithelium. J Clin Invest. 1998 Oct 1;102(7):1321–1331. doi: 10.1172/JCI1516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gailit J., Clark R. A. Wound repair in the context of extracellular matrix. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994 Oct;6(5):717–725. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetzl E. J., Banda M. J., Leppert D. Matrix metalloproteinases in immunity. J Immunol. 1996 Jan 1;156(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez D. E., Alonso D. F., Yoshiji H., Thorgeirsson U. P. Tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases: structure, regulation and biological functions. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997 Oct;74(2):111–122. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham M. F., Willey A., Zhu Y. N., Yager D. R., Sugerman H. J., Diegelmann R. F. Corticosteroids repress the interleukin 1 beta-induced secretion of collagenase in human intestinal smooth muscle cells. Gastroenterology. 1997 Dec;113(6):1924–1929. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70012-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gumaste V., Sachar D. B., Greenstein A. J. Benign and malignant colorectal strictures in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1992 Jul;33(7):938–941. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.7.938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammani K., Blakis A., Morsette D., Bowcock A. M., Schmutte C., Henriet P., DeClerck Y. A. Structure and characterization of the human tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-2 gene. J Biol Chem. 1996 Oct 11;271(41):25498–25505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelstein B. P., Canete-Soler R., Bernhard E. J., Dilks D. W., Muschel R. J. Metalloproteinases in tumor progression: the contribution of MMP-9. Invasion Metastasis. 1994;14(1-6):246–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraoka N., Allen E., Apel I. J., Gyetko M. R., Weiss S. J. Matrix metalloproteinases regulate neovascularization by acting as pericellular fibrinolysins. Cell. 1998 Oct 30;95(3):365–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81768-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S. M., Raine L., Fanger H. Use of avidin-biotin-peroxidase complex (ABC) in immunoperoxidase techniques: a comparison between ABC and unlabeled antibody (PAP) procedures. J Histochem Cytochem. 1981 Apr;29(4):577–580. doi: 10.1177/29.4.6166661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito A., Sato T., Iga T., Mori Y. Tumor necrosis factor bifunctionally regulates matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases (TIMP) production by human fibroblasts. FEBS Lett. 1990 Aug 20;269(1):93–95. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81127-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C. F., Mata M., Fink D. J. Rapid construction of deleted DNA fragments for use as internal standards in competitive PCR. PCR Methods Appl. 1994 Feb;3(4):252–255. doi: 10.1101/gr.3.4.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K., Lein M., Ulbrich N., Rudolph B., Henke W., Schnorr D., Loening S. A. Quantification of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinase in prostatic tissue: analytical aspects. Prostate. 1998 Feb 1;34(2):130–136. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19980201)34:2<130::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn E. C., Jacobs W., Kim Y. S., Alessandro R., Stetler-Stevenson W. G., Liotta L. A. Calcium influx modulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase-2 (72-kDa type IV collagenase, gelatinase A). J Biol Chem. 1994 Aug 26;269(34):21505–21511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs E. J., DiPietro L. A. Fibrogenic cytokines and connective tissue production. FASEB J. 1994 Aug;8(11):854–861. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.8.11.7520879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krane S. M. Clinical importance of metalloproteinases and their inhibitors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994 Sep 6;732:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacraz S., Isler P., Vey E., Welgus H. G., Dayer J. M. Direct contact between T lymphocytes and monocytes is a major pathway for induction of metalloproteinase expression. J Biol Chem. 1994 Sep 2;269(35):22027–22033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lohi J., Keski-Oja J. Calcium ionophores decrease pericellular gelatinolytic activity via inhibition of 92-kDa gelatinase expression and decrease of 72-kDa gelatinase activation. J Biol Chem. 1995 Jul 21;270(29):17602–17609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massova I., Kotra L. P., Fridman R., Mobashery S. Matrix metalloproteinases: structures, evolution, and diversification. FASEB J. 1998 Sep;12(12):1075–1095. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes H., Herbst H., Schuppan D., Stallmach A., Milani S., Stein H., Riecken E. O. Cellular localization of procollagen gene transcripts in inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 1992 Feb;102(2):431–442. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90087-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthes H., Stallmach A., Matthes B., Herbst H., Schuppan D., Riecken E. O. Hinweise für einen differenten Kollagenmetabolismus bei Morbus Crohn und Colitis ulcerosa. Med Klin (Munich) 1993 Apr 15;88(4):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagase H. Activation mechanisms of matrix metalloproteinases. Biol Chem. 1997 Mar-Apr;378(3-4):151–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani H., Nagai T., Nagura H. Similarities of in situ mRNA expression between gelatinase A (MMP-2) and type I procollagen in human gastrointestinal carcinoma: comparison with granulation tissue reaction. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1995 Sep;86(9):833–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1995.tb03093.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani H. Stromal reaction in cancer tissue: pathophysiologic significance of the expression of matrix-degrading enzymes in relation to matrix turnover and immune/inflammatory reactions. Pathol Int. 1998 Jan;48(1):1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1998.tb03820.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohuchi E., Imai K., Fujii Y., Sato H., Seiki M., Okada Y. Membrane type 1 matrix metalloproteinase digests interstitial collagens and other extracellular matrix macromolecules. J Biol Chem. 1997 Jan 24;272(4):2446–2451. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada A., Tomasetto C., Lutz Y., Bellocq J. P., Rio M. C., Basset P. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases during rat skin wound healing: evidence that membrane type-1 matrix metalloproteinase is a stromal activator of pro-gelatinase A. J Cell Biol. 1997 Apr 7;137(1):67–77. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pender S. L., Breese E. J., Günther U., Howie D., Wathen N. C., Schuppan D., MacDonald T. T. Suppression of T cell-mediated injury in human gut by interleukin 10: role of matrix metalloproteinases. Gastroenterology. 1998 Sep;115(3):573–583. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70136-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pender S. L., Tickle S. P., Docherty A. J., Howie D., Wathen N. C., MacDonald T. T. A major role for matrix metalloproteinases in T cell injury in the gut. J Immunol. 1997 Feb 15;158(4):1582–1590. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilcher B. K., Dumin J. A., Sudbeck B. D., Krane S. M., Welgus H. G., Parks W. C. The activity of collagenase-1 is required for keratinocyte migration on a type I collagen matrix. J Cell Biol. 1997 Jun 16;137(6):1445–1457. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podolsky D. K. Healing the epithelium: solving the problem from two sides. J Gastroenterol. 1997 Feb;32(1):122–126. doi: 10.1007/BF01213309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan M. E., Ramamurthy S., Golub L. M. Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibition in periodontal treatment. Curr Opin Periodontol. 1996;3:85–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarialho-Kere U. K. Patterns of matrix metalloproteinase and TIMP expression in chronic ulcers. Arch Dermatol Res. 1998 Jul;290 (Suppl):S47–S54. doi: 10.1007/pl00007453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saarialho-Kere U. K., Vaalamo M., Puolakkainen P., Airola K., Parks W. C., Karjalainen-Lindsberg M. L. Enhanced expression of matrilysin, collagenase, and stromelysin-1 in gastrointestinal ulcers. Am J Pathol. 1996 Feb;148(2):519–526. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato H., Seiki M. Membrane-type matrix metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs) in tumor metastasis. J Biochem. 1996 Feb;119(2):209–215. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a021223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro S. D., Kobayashi D. K., Welgus H. G. Identification of TIMP-2 in human alveolar macrophages. Regulation of biosynthesis is opposite to that of metalloproteinases and TIMP-1. J Biol Chem. 1992 Jul 15;267(20):13890–13894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southwood T. R. Report from a symposium on corticosteroid therapy in juvenile chronic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 1993 Jan-Feb;11(1):91–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRUELOVE S. C., RICHARDS W. C. Biopsy studies in ulcerative colitis. Br Med J. 1956 Jun 9;1(4979):1315–1318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.4979.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Théret N., Musso O., L'Helgoualc'h A., Campion J. P., Clément B. Differential expression and origin of membrane-type 1 and 2 matrix metalloproteinases (MT-MMPs) in association with MMP2 activation in injured human livers. Am J Pathol. 1998 Sep;153(3):945–954. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65636-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timperley W. R. Selling the pathology service. BMJ. 1990 Oct 13;301(6756):828–828. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6756.828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno H., Nakamura H., Inoue M., Imai K., Noguchi M., Sato H., Seiki M., Okada Y. Expression and tissue localization of membrane-types 1, 2, and 3 matrix metalloproteinases in human invasive breast carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1997 May 15;57(10):2055–2060. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaalamo M., Karjalainen-Lindsberg M. L., Puolakkainen P., Kere J., Saarialho-Kere U. Distinct expression profiles of stromelysin-2 (MMP-10), collagenase-3 (MMP-13), macrophage metalloelastase (MMP-12), and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-3 (TIMP-3) in intestinal ulcerations. Am J Pathol. 1998 Apr;152(4):1005–1014. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vassalli J. D., Saurat J. H. Cuts and scrapes? Plasmin heals! Nat Med. 1996 Mar;2(3):284–285. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Keiser J. A. Vascular endothelial growth factor upregulates the expression of matrix metalloproteinases in vascular smooth muscle cells: role of flt-1. Circ Res. 1998 Oct 19;83(8):832–840. doi: 10.1161/01.res.83.8.832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welgus H. G., Senior R. M., Parks W. C., Kahn A. J., Ley T. J., Shapiro S. D., Campbell E. J. Neutral proteinase expression by human mononuclear phagocytes: a prominent role of cellular differentiation. Matrix Suppl. 1992;1:363–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woessner J. F., Jr Matrix metalloproteinases and their inhibitors in connective tissue remodeling. FASEB J. 1991 May;5(8):2145–2154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]