Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS—A histopathological feature considered indicative of ulcerative colitis (UC) is the so-called basal lymphoid aggregates. Their relevance in the pathogenesis of UC is, however, unknown. We have performed a comprehensive analysis of the immune cells in these aggregates most likely corresponding to the lymphoid follicular hyperplasia also described in other colitides. METHODS—Resection specimens of UC and normal colon were analysed by immunomorphometry, immunoflow cytometry, and immunoelectron microscopy, using a large panel of monoclonal antibodies. RESULTS—(1) In all cases of UC, colonic lamina propria contained numerous basal aggregates composed of lymphocytes, follicular dendritic cells, and CD80/B7.1 positive dendritic cells. (2) CD4+CD28 αβ T cells and B cells were the dominant cell types in the aggregates. (3) The aggregates contained a large fraction of cells that are normally associated with the epithelium: that is, γδ T cells (11 (7)%) and αEβ7+ cells (26 (13)%). The γδ T cells used Vδ1 and were CD4 CD8 . Immunoelectron microscopy analysis demonstrated TcR-γδ internalisation and surface downregulation, indicating that the γδ T cells were activated and engaged in the disease process. (4) One third of cells in the aggregates expressed the antiapoptotic protein bcl-2. CONCLUSIONS—Basal lymphoid aggregates in UC colon are a consequence of anomalous lymphoid follicular hyperplasia, characterised by abnormal follicular architecture and unusual cell immunophenotypes. The aggregates increase in size with severity of disease, and contain large numbers of apoptosis resistant cells and activated mucosal γδ T cells. The latter probably colonise the aggregates as an immunoregulatory response to stressed lymphocytes or as a substitute for defective T helper cells in B cell activation. γδ T cells in the aggregates may be characteristic of UC. Keywords: basal lymphoid aggregates; ulcerative colitis; T cell receptor γδ; immunomorphology

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (376.7 KB).

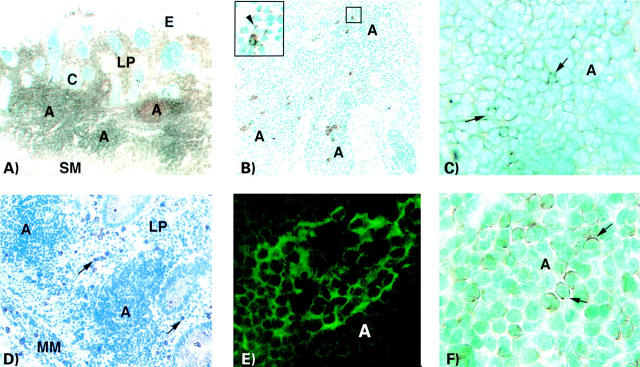

Figure 1 .

Immunoperoxidase (A, B, C, D, F) and immunofluorescence (E) staining of basal lymphoid aggregates in ulcerative colitis colon. (A) Section stained with anti-CD45 monoclonal antibody (mAb). Three aggregates ("A") can be seen in the enlarged lamina propria (LP) in close proximity to the submucosa (SM). Large numbers of scattered CD45+ cells can also be seen in the lamina propria outside the aggregates. Several deep crypts ("C") extend into the lamina propria. The number of goblet cells is significantly reduced in cryptal and luminal epithelia ("E") (×18). (B) Section stained with a mixture of anti-pan TcR-γδ mAbs (TCRδ1, δTCS1, and Vδ1) showing several γδ T cells scattered throughout the aggregate. Inset: One γδ T cell with cytoplasmic staining and single cells with dotted staining (arrowhead) (×55, inset ×220). (C) Aggregate ("A") in a section stained with anti-αE/CD103 mAb. Cells with membrane staining are frequent. Arrows indicate strongly stained cells (×220). (D) Section stained with anti-CD28 mAb. CD28 expressing cells cannot be detected in the aggregates ("A") but are frequent in lamina propria (LP) outside the aggregates (arrows). Intraepithelial CD28+ cells are scarce (×32). (E) Section stained with anti-CD80 (B7.1) mAb. A dendritic cell network of CD80 positive cells in an aggregate ("A") is seen (×160). (F) Aggregate ("A") in a section stained with anti-bcl-2 mAb. A high proportion of the cells show cytoplasmic staining for the bcl-2 protein. Arrows indicate typical stained cells (×320). A, aggregate; C, crypt; E, luminal epithelium; LP, lamina propria; MM, muscularis mucosae; SM, submucosa.

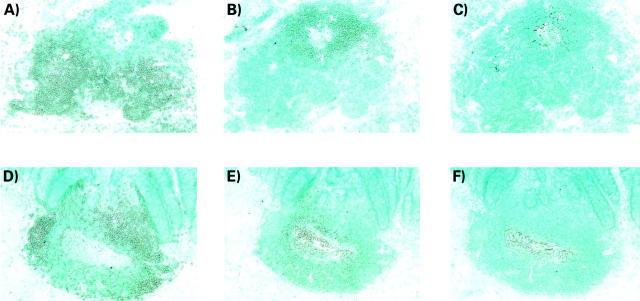

Figure 2 .

Immunoperoxidase staining of sequential sections of basal lymphoid aggregates in ulcerative colitis colon (A, B, C) and of solitary follicles in normal colon (D, E, F). (A) Section stained with anti-CD3 mAb showing an aggregate with numerous positive cells concentrated in two main areas and a few scattered cells in the reciprocal B cell area. (B) The same aggregate as in (A) stained with a mixture of anti-CD19 mAb, anti-CD20 mAb, and anti-CD22 mAb. Positive cells are localised in the area with only a few scattered CD3+ cells. (C) The same aggregate as in (A) stained with anti-FDC mAb Ki-M4 showing a follicular dendritic cell network localised to the B cell area. (D) Section of a normal solitary follicle stained with anti-CD3 mAb. CD3+ cells are mainly found in three clusters localised in the outer rim of the follicle. (E) The same follicle as in (D) stained with a mixture of anti-CD19 mAb, anti-CD20 mAb, and anti-CD22 mAb. Positive cells are localised in the centre of the follicle. Note a central zone of large loosely packed positive cells surrounded by more tightly packed small positive cells. (F) The same follicle as in (D) stained with anti-FDC mAb Ki-M4 showing the follicular dendritic cell network localised to the centre of the B cell area. Original magnifications, A-F, ×55.

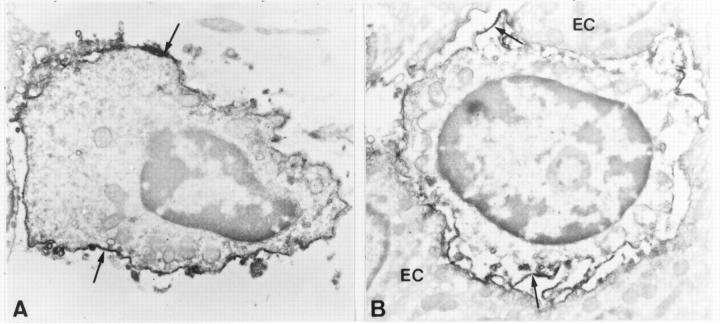

Figure 3 .

Immunomorphometric analysis of basal lymphoid aggregates in ulcerative colitis (UC) colon and solitary follicles in control colon. Bars represent mean (SD) per cent positive cells of all cells in the aggregate/follicle, as determined by morphometric counting of immunohistochemically stained cryosections. Nine UC colon samples (six severe, three moderate) were counted. Solitary follicles in 6-8 control colon samples were analysed for all markers except CD68, in which case n=2. An indirect immunoperoxidase technique was used for staining with anti-CD3, anti-TcR-αβ, anti-CD4, anti-CD8, anti-CD19/CD20/CD22, anti-CD57, anti-CD15, anti-CD14, and anti-CD68 monoclonal antibodies (mAb). Indirect immunofluorescence was used for staining with anti-TcR-γδ mAb. ***p<0.001, aggregates in UC compared with solitary follicles in control colon.

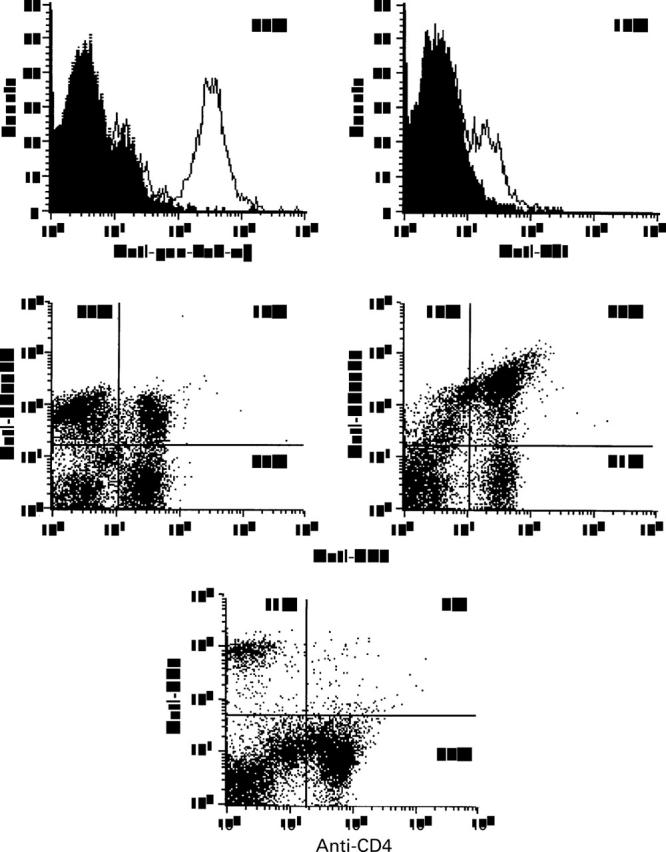

Figure 4 .

Flow cytometry analysis of high density lamina propria leucocytes isolated from one ulcerative colitis (UC) colon sample. Cells were stained with phycoerythrin labelled anti-pan-TcR-αβ monoclonal antibody (mAb) (BMA031) and with anti-Vδ1 mAb (δTCS1) for indirect immunofluorescence. The shaded histograms superimposed on the graphs show the negative controls. Expression of CD45R0 and CD45RA by T cells was assayed using PerCP labelled anti-CD3 mAb (SK7) and FITC labelled anti-CD45RA mAb (L28), and anti-CD45R0 mAb (UCHL-1), respectively. CD4 and CD8 positive cells were determined by two colour immunoflow cytometry using FITC labelled anti-CD4 mAb (MT310) and phycoerythrin labelled anti-CD8 mAb (DK25). Cells incubated with irrelevant fluorochrome conjugated mAbs served as negative controls and were used to determine the position of quadrant regions.

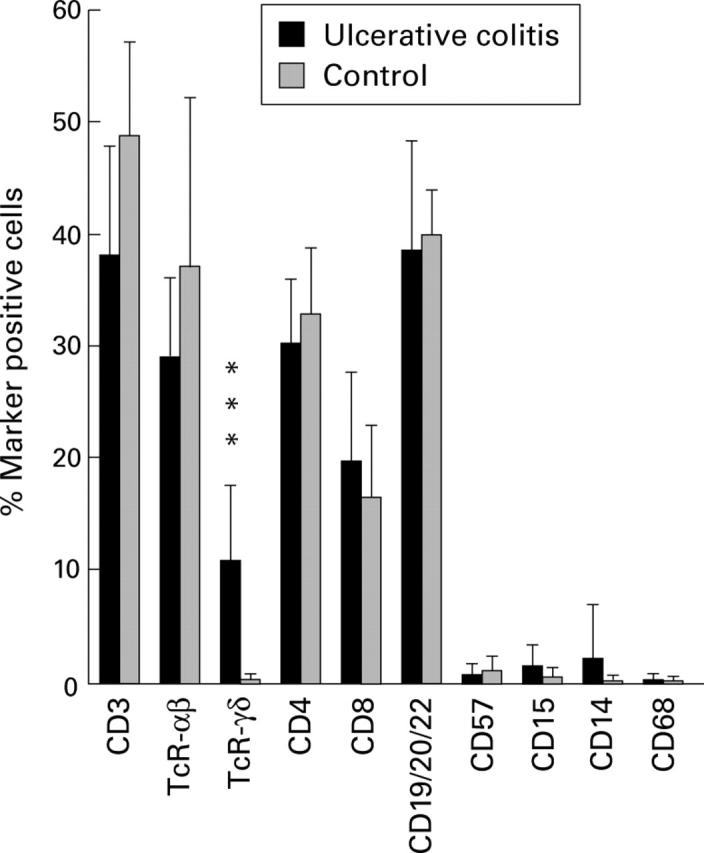

Figure 5 .

Immunoelectron micrographs of γδ T lymphocytes in normal colon. (A) A characteristic lamina propria γδ T cell showing homogeneous surface staining (arrows). (B) An intraepithelial γδ T cell showing diffuse surface staining (arrows). EC, epithelial cell. All ultrathin sections were examined without additional staining. Original magnification: A ×12 000; B ×11 500.

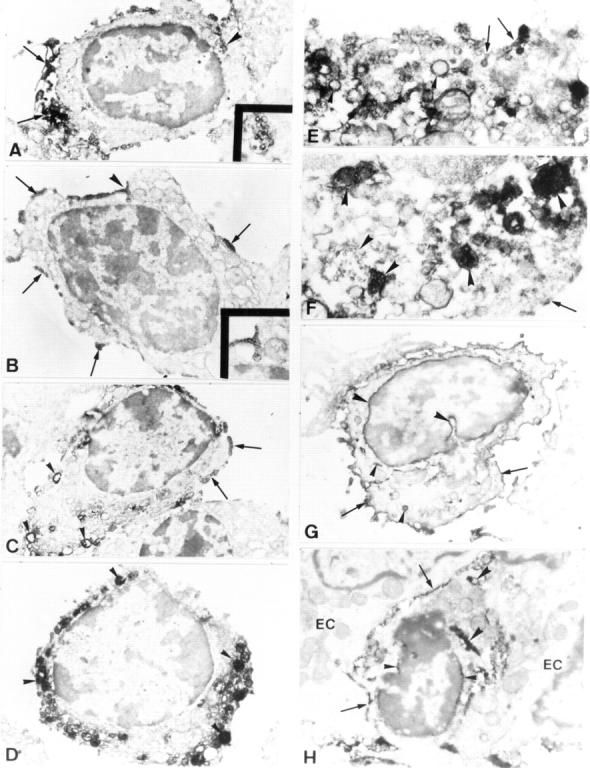

Figure 6 .

Immunoelectron micrographs of lamina propria (A-G) and intraepithelial (H) γδ T cells in ulcerative colitis colon. (A) Low power micrograph of a γδ T lymphocyte with numerous surface processes which are distinctly stained by the reaction product and concentrated at one pole of the cell (arrows). The rest of the cell surface is weakly stained. Inset: High magnification of the positively stained multivesicular body indicated by the arrowhead. (B) A γδ T cell showing the surface depositions of the reaction product which have the appearance of scarce clusters (arrows). One of the clusters is located over the surface flask-shaped invagination (arrowhead and in the inset at higher magnification). (C) A γδ T cell displaying the clustered reaction product on the cell surface (arrows) and numerous positively stained cytoplasmic vacuoles near the cell membrane (arrowheads). (D) A γδ T cell showing only numerous cytoplasmic vesicles and vacuoles of diverse sizes near the cell membrane and deep in the cell. The lumen of these structures exhibit variable intense staining by the reaction product (arrowheads). (E) A portion of the γδ T cell cytoplasm showing cytoplasmic vesicles that are connected with the plasma membrane and contain the reaction product (arrows). In addition, the cytoplasm contains numerous positively stained vacuoles (arrowheads). (F) A portion of the γδ T cell cytoplasm showing numerous multivesicular bodies mainly consisting of tightly packed positively stained microvesicles (arrowheads). Arrow depicts a small cluster of the reaction product on the cell surface. (G) A γδ T lymphocyte showing a strong positive staining of the cell surface (arrows) and the perinuclear space (large arrowheads). Small arrowheads indicate the positive staining of single cytoplasmic vacuoles. (H) A γδ T lymphocyte showing the positive staining of the cell surface (arrows) and perinuclear space (small arrowheads). Large arrowheads indicate the positively stained cisternal structure in the cytoplasm. EC, epithelial cell. All ultrathin sections were examined without additional staining. Original magnification: A ×8600, inset ×25 000; B ×9000, inset ×20 000; C ×8000; D ×9500; E ×29 500; F ×31 000; G ×10 000; H ×12 500.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arató A., Savilahti E., Tainio V. M., Klemola T. Immunohistochemical study of lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate and epithelial HLA-DR expression in the rectal and colonic mucosae of children with ulcerative colitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1989 Feb;8(2):172–180. doi: 10.1097/00005176-198902000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROBERGER O., PERLMANN P. Autoantibodies in human ulcerative colitis. J Exp Med. 1959 Nov 1;110:657–674. doi: 10.1084/jem.110.5.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beagley K. W., Elson C. O. Cells and cytokines in mucosal immunity and inflammation. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992 Jun;21(2):347–366. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucht A., Söderström K., Esin S., Grunewald J., Hagelberg S., Magnusson I., Wigzell H., Grönberg A., Kiessling R. Analysis of gamma delta V region usage in normal and diseased human intestinal biopsies and peripheral blood by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and flow cytometry. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995 Jan;99(1):57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03472.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Z., Kishimoto H., Brunmark A., Jackson M. R., Peterson P. A., Sprent J. Requirements for peptide-induced T cell receptor downregulation on naive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997 Feb 17;185(4):641–651. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong Y., Brandwein S. L., McCabe R. P., Lazenby A., Birkenmeier E. H., Sundberg J. P., Elson C. O. CD4+ T cells reactive to enteric bacterial antigens in spontaneously colitic C3H/HeJBir mice: increased T helper cell type 1 response and ability to transfer disease. J Exp Med. 1998 Mar 16;187(6):855–864. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.6.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cory S. Regulation of lymphocyte survival by the bcl-2 gene family. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:513–543. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.002501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K. M., Dasgupta A., Mandal A., Geng X. Autoimmunity to cytoskeletal protein tropomyosin. A clue to the pathogenetic mechanism for ulcerative colitis. J Immunol. 1993 Mar 15;150(6):2487–2493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deusch K., Lüling F., Reich K., Classen M., Wagner H., Pfeffer K. A major fraction of human intraepithelial lymphocytes simultaneously expresses the gamma/delta T cell receptor, the CD8 accessory molecule and preferentially uses the V delta 1 gene segment. Eur J Immunol. 1991 Apr;21(4):1053–1059. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830210429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duchmann R., Kaiser I., Hermann E., Mayet W., Ewe K., Meyer zum Büschenfelde K. H. Tolerance exists towards resident intestinal flora but is broken in active inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) Clin Exp Immunol. 1995 Dec;102(3):448–455. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1995.tb03836.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima K., Masuda T., Ohtani H., Sasaki I., Funayama Y., Matsuno S., Nagura H. Immunohistochemical characterization, distribution, and ultrastructure of lymphocytes bearing T-cell receptor gamma/delta in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1991 Sep;101(3):670–678. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90524-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giacomelli R., Parzanese I., Frieri G., Passacantando A., Pizzuto F., Pimpo T., Cipriani P., Viscido A., Caprilli R., Tonietti G. Increase of circulating gamma/delta T lymphocytes in the peripheral blood of patients affected by active inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994 Oct;98(1):83–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06611.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groh V., Steinle A., Bauer S., Spies T. Recognition of stress-induced MHC molecules by intestinal epithelial gammadelta T cells. Science. 1998 Mar 13;279(5357):1737–1740. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5357.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J., Maxfield F. R. Membrane transport in the endocytic pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1995 Aug;7(4):552–563. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(95)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstensen T. S., Mollnes T. E., Garred P., Fausa O., Brandtzaeg P. Epithelial deposition of immunoglobulin G1 and activated complement (C3b and terminal complement complex) in ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1990 May;98(5 Pt 1):1264–1271. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halstensen T. S., Scott H., Brandtzaeg P. Intraepithelial T cells of the TcR gamma/delta+ CD8- and V delta 1/J delta 1+ phenotypes are increased in coeliac disease. Scand J Immunol. 1989 Dec;30(6):665–672. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1989.tb02474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haque S., Eisen R. N., West A. B. The morphologic features of diversion colitis: studies of a pediatric population with no other disease of the intestinal mucosa. Hum Pathol. 1993 Feb;24(2):211–219. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(93)90303-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata I., Berrebi G., Austin L. L., Keren D. F., Dobbins W. O., 3rd Immunohistological characterization of intraepithelial and lamina propria lymphocytes in control ileum and colon and in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1986 Jun;31(6):593–603. doi: 10.1007/BF01318690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holländer G. A., Simpson S. J., Mizoguchi E., Nichogiannopoulou A., She J., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C., Bhan A. K., Burakoff S. J., Wang B., Terhorst C. Severe colitis in mice with aberrant thymic selection. Immunity. 1995 Jul;3(1):27–38. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90156-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarry A., Cerf-Bensussan N., Brousse N., Selz F., Guy-Grand D. Subsets of CD3+ (T cell receptor alpha/beta or gamma/delta) and CD3- lymphocytes isolated from normal human gut epithelium display phenotypical features different from their counterparts in peripheral blood. Eur J Immunol. 1990 May;20(5):1097–1103. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830200523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozarek R. A. Review article: immunosuppressive therapy for inflammatory bowel disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1993 Apr;7(2):117–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1993.tb00079.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühn R., Löhler J., Rennick D., Rajewsky K., Müller W. Interleukin-10-deficient mice develop chronic enterocolitis. Cell. 1993 Oct 22;75(2):263–274. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80068-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagercrantz R., Hammarström S., Perlmann P., Gustafsson B. E. Immunological studies in ulcerative colitis. IV. Origin of autoantibodies. J Exp Med. 1968 Dec 1;128(6):1339–1352. doi: 10.1084/jem.128.6.1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichtiger S., Present D. H., Kornbluth A., Gelernt I., Bauer J., Galler G., Michelassi F., Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. N Engl J Med. 1994 Jun 30;330(26):1841–1845. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199406303302601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindstein T., June C. H., Ledbetter J. A., Stella G., Thompson C. B. Regulation of lymphokine messenger RNA stability by a surface-mediated T cell activation pathway. Science. 1989 Apr 21;244(4902):339–343. doi: 10.1126/science.2540528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist C., Baranov V., Hammarström S., Athlin L., Hammarström M. L. Intra-epithelial lymphocytes. Evidence for regional specialization and extrathymic T cell maturation in the human gut epithelium. Int Immunol. 1995 Sep;7(9):1473–1487. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.9.1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist C., Hammarström M. L., Athlin L., Hammarström S. Isolation of functionally active intraepithelial lymphocytes and enterocytes from human small and large intestine. J Immunol Methods. 1992 Aug 10;152(2):253–263. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(92)90147-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundqvist C., Hammarström M. L. T-cell receptor gamma delta-expressing intraepithelial lymphocytes are present in normal and chronically inflamed human gingiva. Immunology. 1993 May;79(1):38–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Löfberg R., Danielsson A., Suhr O., Nilsson A., Schiöler R., Nyberg A., Hultcrantz R., Kollberg B., Gillberg R., Willén R. Oral budesonide versus prednisolone in patients with active extensive and left-sided ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jun;110(6):1713–1718. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8964395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macpherson A., Khoo U. Y., Forgacs I., Philpott-Howard J., Bjarnason I. Mucosal antibodies in inflammatory bowel disease are directed against intestinal bacteria. Gut. 1996 Mar;38(3):365–375. doi: 10.1136/gut.38.3.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeurer M. J., Martin D., Walter W., Liu K., Zitvogel L., Halusczcak K., Rabinowich H., Duquesnoy R., Storkus W., Lotze M. T. Human intestinal Vdelta1+ lymphocytes recognize tumor cells of epithelial origin. J Exp Med. 1996 Apr 1;183(4):1681–1696. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVay L. D., Li B., Biancaniello R., Creighton M. A., Bachwich D., Lichtenstein G., Rombeau J. L., Carding S. R. Changes in human mucosal gamma delta T cell repertoire and function associated with the disease process in inflammatory bowel disease. Mol Med. 1997 Mar;3(3):183–203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincheva-Nilsson L., Hammarström S., Hammarström M. L. Human decidual leukocytes from early pregnancy contain high numbers of gamma delta+ cells and show selective down-regulation of alloreactivity. J Immunol. 1992 Sep 15;149(6):2203–2211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mincheva-Nilsson L., Kling M., Hammarström S., Nagaeva O., Sundqvist K. G., Hammarström M. L., Baranov V. Gamma delta T cells of human early pregnancy decidua: evidence for local proliferation, phenotypic heterogeneity, and extrathymic differentiation. J Immunol. 1997 Oct 1;159(7):3266–3277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrissey P. J., Charrier K., Braddy S., Liggitt D., Watson J. D. CD4+ T cells that express high levels of CD45RB induce wasting disease when transferred into congenic severe combined immunodeficient mice. Disease development is prevented by cotransfer of purified CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1993 Jul 1;178(1):237–244. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.1.237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagashima R., Maeda K., Imai Y., Takahashi T. Lamina propria macrophages in the human gastrointestinal mucosa: their distribution, immunohistological phenotype, and function. J Histochem Cytochem. 1996 Jul;44(7):721–731. doi: 10.1177/44.7.8675993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedergang F., Dautry-Varsat A., Alcover A. Peptide antigen or superantigen-induced down-regulation of TCRs involves both stimulated and unstimulated receptors. J Immunol. 1997 Aug 15;159(4):1703–1710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Leary A. D., Sweeney E. C. Lymphoglandular complexes of the colon: structure and distribution. Histopathology. 1986 Mar;10(3):267–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1986.tb02481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odze R., Antonioli D., Peppercorn M., Goldman H. Effect of topical 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA) therapy on rectal mucosal biopsy morphology in chronic ulcerative colitis. Am J Surg Pathol. 1993 Sep;17(9):869–875. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199309000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohteki T., MacDonald H. R. Expression of the CD28 costimulatory molecule on subsets of murine intestinal intraepithelial lymphocytes correlates with lineage and responsiveness. Eur J Immunol. 1993 Jun;23(6):1251–1255. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pileri S. A., Roncador G., Ceccarelli C., Piccioli M., Briskomatis A., Sabattini E., Ascani S., Santini D., Piccaluga P. P., Leone O. Antigen retrieval techniques in immunohistochemistry: comparison of different methods. J Pathol. 1997 Sep;183(1):116–123. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199709)183:1<116::AID-PATH1087>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powrie F., Leach M. W., Mauze S., Caddle L. B., Coffman R. L. Phenotypically distinct subsets of CD4+ T cells induce or protect from chronic intestinal inflammation in C. B-17 scid mice. Int Immunol. 1993 Nov;5(11):1461–1471. doi: 10.1093/intimm/5.11.1461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph U., Finegold M. J., Rich S. S., Harriman G. R., Srinivasan Y., Brabet P., Boulay G., Bradley A., Birnbaumer L. Ulcerative colitis and adenocarcinoma of the colon in G alpha i2-deficient mice. Nat Genet. 1995 Jun;10(2):143–150. doi: 10.1038/ng0695-143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rugtveit J., Bakka A., Brandtzaeg P. Differential distribution of B7.1 (CD80) and B7.2 (CD86) costimulatory molecules on mucosal macrophage subsets in human inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Clin Exp Immunol. 1997 Oct;110(1):104–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.5071404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadlack B., Merz H., Schorle H., Schimpl A., Feller A. C., Horak I. Ulcerative colitis-like disease in mice with a disrupted interleukin-2 gene. Cell. 1993 Oct 22;75(2):253–261. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80067-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salio M., Valitutti S., Lanzavecchia A. Agonist-induced T cell receptor down-regulation: molecular requirements and dissociation from T cell activation. Eur J Immunol. 1997 Jul;27(7):1769–1773. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S., Raedler A., Stenson W. F., MacDermott R. P. The role of the mucosal immune system in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1992 Jun;21(2):451–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shull M. M., Ormsby I., Kier A. B., Pawlowski S., Diebold R. J., Yin M., Allen R., Sidman C., Proetzel G., Calvin D. Targeted disruption of the mouse transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene results in multifocal inflammatory disease. Nature. 1992 Oct 22;359(6397):693–699. doi: 10.1038/359693a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson S. J., Mizoguchi E., Allen D., Bhan A. K., Terhorst C. Evidence that CD4+, but not CD8+ T cells are responsible for murine interleukin-2-deficient colitis. Eur J Immunol. 1995 Sep;25(9):2618–2625. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz C. M., Belic L. Rectal biopsy helps to distinguish acute self-limited colitis from idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1984 Jan;86(1):104–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surawicz C. M., Haggitt R. C., Husseman M., McFarland L. V. Mucosal biopsy diagnosis of colitis: acute self-limited colitis and idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1994 Sep;107(3):755–763. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderström K., Halapi E., Nilsson E., Grönberg A., van Embden J., Klareskog L., Kiessling R. Synovial cells responding to a 65-kDa mycobacterial heat shock protein have a high proportion of a TcR gamma delta subtype uncommon in peripheral blood. Scand J Immunol. 1990 Nov;32(5):503–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.1990.tb03191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi F., Das K. M. Isolation and characterization of a colonic autoantigen specifically recognized by colon tissue-bound immunoglobulin G from idiopathic ulcerative colitis. J Clin Invest. 1985 Jul;76(1):311–318. doi: 10.1172/JCI111963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targan S. R., Landers C. J., Cobb L., MacDermott R. P., Vidrich A. Perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies are spontaneously produced by mucosal B cells of ulcerative colitis patients. J Immunol. 1995 Sep 15;155(6):3262–3267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trejdosiewicz L. K., Calabrese A., Smart C. J., Oakes D. J., Howdle P. D., Crabtree J. E., Losowsky M. S., Lancaster F., Boylston A. W. Gamma delta T cell receptor-positive cells of the human gastrointestinal mucosa: occurrence and V region gene expression in Heliobacter pylori-associated gastritis, coeliac disease and inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Exp Immunol. 1991 Jun;84(3):440–444. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyemura K., Ho C. T., Ohmen J. D., Rea T. H., Modlin R. L. Selective expansion of V delta 1 + T cells from leprosy skin lesions. J Invest Dermatol. 1992 Dec;99(6):848–852. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12614809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyemura K., Klotz J., Pirmez C., Ohmen J., Wang X. H., Ho C., Hoffman W. L., Modlin R. L. Microanatomic clonality of gamma delta T cells in human leishmaniasis lesions. J Immunol. 1992 Feb 15;148(4):1205–1211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S., Müller S., Cella M., Padovan E., Lanzavecchia A. Serial triggering of many T-cell receptors by a few peptide-MHC complexes. Nature. 1995 May 11;375(6527):148–151. doi: 10.1038/375148a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valitutti S., Müller S., Salio M., Lanzavecchia A. Degradation of T cell receptor (TCR)-CD3-zeta complexes after antigenic stimulation. J Exp Med. 1997 May 19;185(10):1859–1864. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.10.1859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viola A., Lanzavecchia A. T cell activation determined by T cell receptor number and tunable thresholds. Science. 1996 Jul 5;273(5271):104–106. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5271.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weibel E. R., Kistler G. S., Scherle W. F. Practical stereological methods for morphometric cytology. J Cell Biol. 1966 Jul;30(1):23–38. doi: 10.1083/jcb.30.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L., Pao W., Wong F. S., Peng Q., Craft J., Zheng B., Kelsoe G., Dianda L., Owen M. J., Hayday A. C. Germinal center formation, immunoglobulin class switching, and autoantibody production driven by "non alpha/beta" T cells. J Exp Med. 1996 May 1;183(5):2271–2282. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.5.2271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen L., Roberts S. J., Viney J. L., Wong F. S., Mallick C., Findly R. C., Peng Q., Craft J. E., Owen M. J., Hayday A. C. Immunoglobulin synthesis and generalized autoimmunity in mice congenitally deficient in alpha beta(+) T cells. Nature. 1994 Jun 23;369(6482):654–658. doi: 10.1038/369654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yacyshyn B. R. Activated CD19+ B cell lamina propria lymphocytes in ulcerative colitis. Immunol Cell Biol. 1993 Aug;71(Pt 4):265–274. doi: 10.1038/icb.1993.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]