Abstract

BACKGROUND—Dietary fibres have been proposed as protective agents against colon cancer but results of both epidemiological and experimental studies are inconclusive. AIMS—Hypothesising that protection against colon cancer may be restricted to butyrate producing fibres, we investigated the factors needed for long term stable butyrate production and its relation to susceptibility to colon cancer. METHODS—A two part randomised blinded study in rats, mimicking a prospective study in humans, was performed using a low fibre control diet (CD) and three high fibre diets: starch free wheat bran (WB), type III resistant starch (RS), and short chain fructo-oligosaccharides (FOS). Using a randomised block design, 96 inbred rats were fed for two, 16, 30, or 44 days to determine the period of adaptation to the diets, fermentation profiles, and effects on the colon, including mucosal proliferation on day 44. Subsequently, 36 rats fed the same diets for 44 days were injected with azoxymethane and checked for aberrant crypt foci 30 days later. RESULTS—After fermentation had stabilised (44 days), only RS and FOS produced large amounts of butyrate, with a trophic effect in the large intestine. No difference in mucosal proliferation between the diets was noted at this time. In the subsequent experiment one month later, fewer aberrant crypt foci were present in rats fed high butyrate producing diets (RS, p=0.022; FOS, p=0.043). CONCLUSION—A stable butyrate producing colonic ecosystem related to selected fibres appears to be less conducive to colon carcinogenesis. Keywords: fibre; fermentation; butyrate; colon carcinogenesis; aberrant crypt foci; rat

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (242.0 KB).

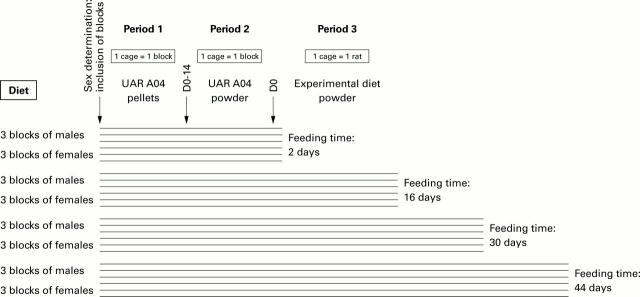

Figure 1 .

Protocol for the study of experimental diet fermentation. Rats (n=96) were randomised before the start of the experiment into 24 blocks (six blocks for each feeding period), one block representing a group of four rats of the same litter and sex. Staggered inclusion of blocks allowed the processing of only one block per sacrifice day, within a period (about one hour) short enough to ensure that all contents could be considered as at the same stage of fermentation. As a possible "experimenter effect" related to the long study period could not be eliminated, inclusion of the 24 blocks was randomised so that all sacrifice days were determined before the experiment began. Blocks were included (median age 46 days) after sex determination and according to these criteria. The four rats of each block, housed in a single cage, were fed successively A03 breeding diet and A04 maintenance diet (UAR). Two weeks before day 0 (D0), rats were housed one per cage and fed powdered maintenance diet. At D0 (median age 72 days), each animal from a block received one of the four experimental diets (table of permutated randomised blocks) and underwent the feeding period allocated by randomisation. Animals were weighed weekly throughout the experiment, from week 1 (at D2) to the day of sacrifice: D16, D30, or D44. Previous studies showed that short chain fatty acid concentrations increased following consumption of the meal and then stabilised during the 8-12 hour postprandial period. Even fed at libitum, rats had the highest consumption of food at the beginning of the dark period. Rats were thus sacrificed 10 hours later, one block at a time, in the order of their codes.

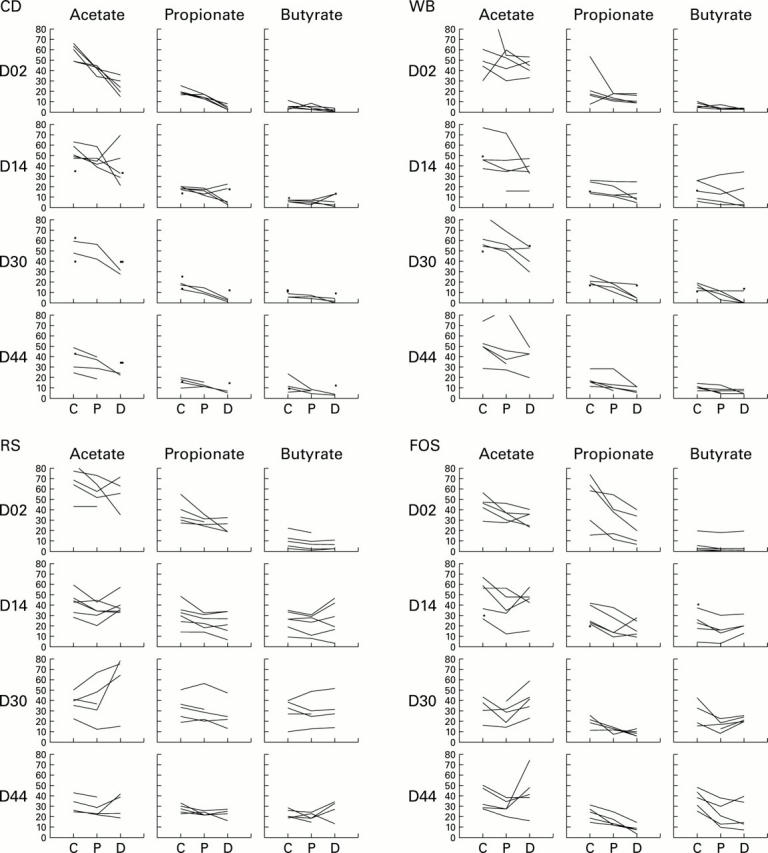

Figure 2 .

Changes over time in the fermentation of the four diets (low fibre control diet (CD), starch free wheat bran enriched diet (WB), type III resistant starch enriched diet (RS), and short chain fructo-oligosaccharide enriched diet (FOS)) along the large intestine. Twenty one blocks (84 rats) instead of 24 were used for this part of the study as some samples were lost. On the y axis are the concentrations of short chain fatty acids (acetate, propionate, and butyrate), expressed in µmol/g wet content. Values from the caecum (C), and proximal (P) and distal (D) colon of each rat are linked together, each line thus representing the individual fermentation pattern along the large intestine of one rat. When there were missing values for proximal colon concentrations (low content), points were plotted to mark the concentrations in the caecum and distal colon, but not linked.

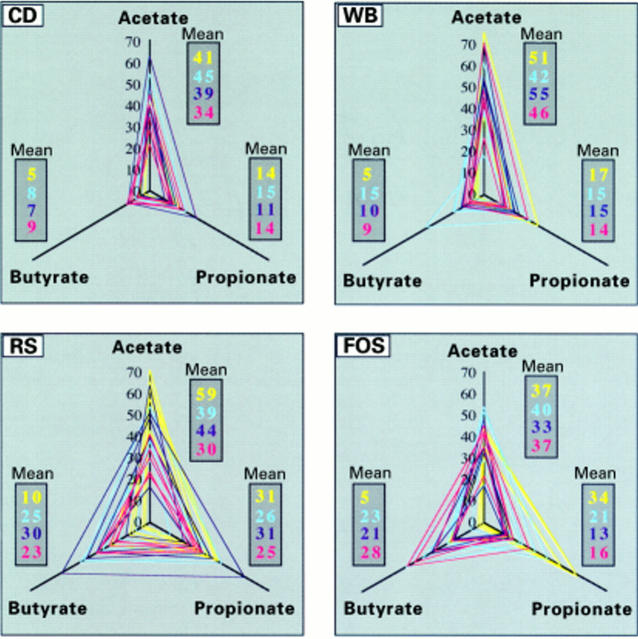

Figure 3 .

Changes over time in the relationships between the major short chain fatty acids (SCFAs) issued from fermentation of the four diets (low fibre control diet (CD), starch free wheat bran enriched diet (WB), type III resistant starch enriched diet (RS), and short chain fructo-oligosaccharide enriched diet (FOS)). The axes indicate individual mean large intestine concentrations (an average of caecum, and proximal and distal colon concentrations, expressed in µmol/g wet content) of acetate, propionate, and butyrate for each rat. These values are linked to form a triangle representing the mean fermentation pattern of the rat. The triangle area is proportional to global SCFA production, and the ratio (relative concentration) of each SCFA can be determined from the shape of the triangle, regardless of its size: the more acute the angle, the higher the ratio. Each dark gray box indicates the mean values of one SCFA concentration for a given time and diet. Colour coding for feeding periods is yellow for D2, blue for D16, dark blue for D30, and red for D44.

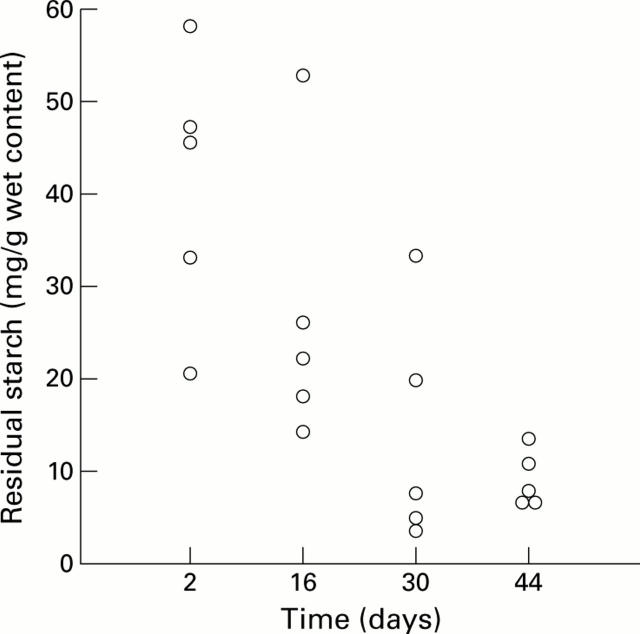

Figure 4 .

Residual starch concentration in the caecum of rats fed the resistant starch enriched diet (RS) for 2, 16, 30, or 44 days. Each point represents one rat.

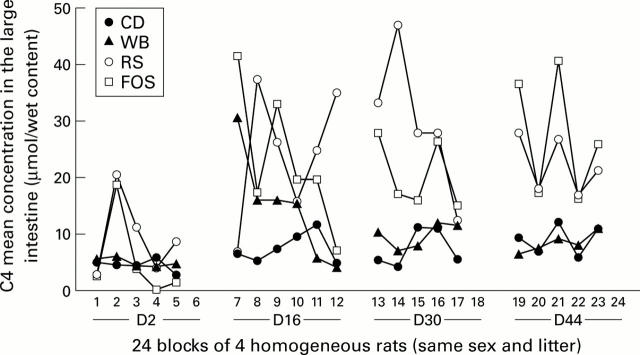

Figure 5 .

Time and interindividual effects on the mean butyrate large intestine concentration (µmol/g wet content) in rats from the 21 blocks (four rats of the same litter, sex, and feeding period) in this part of the study. The four rats of one block are on the same vertical. To facilitate interpretation, lines have been drawn linking the butyrate concentrations of animals fed the same diet for a given period. On D44, mean butyrate concentrations were higher for the short chain fructo-oligosaccharide enriched diet (FOS) than for the type III resistant starch enriched diet (RS), but this was only due to higher caecal concentrations.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alabaster O., Tang Z., Shivapurkar N. Dietary fiber and the chemopreventive modelation of colon carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1996 Feb 19;350(1):185–197. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00114-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alabaster O., Tang Z., Shivapurkar N. Inhibition by wheat bran cereals of the development of aberrant crypt foci and colon tumours. Food Chem Toxicol. 1997 May;35(5):517–522. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(97)00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barsoum G. H., Thompson H., Neoptolemos J. P., Keighley M. R. Dietary calcium does not reduce experimental colorectal carcinogenesis after small bowel resection despite reducing cellular proliferation. Gut. 1992 Nov;33(11):1515–1520. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.11.1515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird R. P. Observation and quantification of aberrant crypts in the murine colon treated with a colon carcinogen: preliminary findings. Cancer Lett. 1987 Oct 30;37(2):147–151. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(87)90157-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boisteau O., Gautier F., Cordel S., Henry F., Harb J., Douillard J. Y., Vallette F. M., Meflah K., Grégoire M. Apoptosis induced by sodium butyrate treatment increases immunogenicity of a rat colon tumor cell line. Apoptosis. 1997;2(4):403–412. doi: 10.1023/a:1026461825570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourquin L. D., Titgemeyer E. C., Garleb K. A., Fahey G. C., Jr Short-chain fatty acid production and fiber degradation by human colonic bacteria: effects of substrate and cell wall fractionation procedures. J Nutr. 1992 Jul;122(7):1508–1520. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.7.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce W. R., Archer M. C., Corpet D. E., Medline A., Minkin S., Stamp D., Yin Y., Zhang X. M. Diet, aberrant crypt foci and colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 1993 Nov;290(1):111–118. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(93)90038-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caderni G., Luceri C., Lancioni L., Tessitore L., Dolara P. Slow-release pellets of sodium butyrate increase apoptosis in the colon of rats treated with azoxymethane, without affecting aberrant crypt foci and colonic proliferation. Nutr Cancer. 1998;30(3):175–181. doi: 10.1080/01635589809514660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caderni G., Stuart E. W., Bruce W. R. Dietary factors affecting the proliferation of epithelial cells in the mouse colon. Nutr Cancer. 1988;11(3):147–153. doi: 10.1080/01635588809513982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. M., Fahey G. C., Jr, Wolf B. W. Selected indigestible oligosaccharides affect large bowel mass, cecal and fecal short-chain fatty acids, pH and microflora in rats. J Nutr. 1997 Jan;127(1):130–136. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.1.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Bingham S. A. Dietary fibre, fermentation and large bowel cancer. Cancer Surv. 1987;6(4):601–621. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings J. H., Englyst H. N. Fermentation in the human large intestine and the available substrates. Am J Clin Nutr. 1987 May;45(5 Suppl):1243–1255. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/45.5.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschner E. E., Ruperto J. F., Lupton J. R., Newmark H. L. Dietary butyrate (tributyrin) does not enhance AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Lett. 1990 Jun 30;52(1):79–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(90)90080-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards C. A., Wilson R. G., Hanlon L., Eastwood M. A. Effect of the dietary fibre content of lifelong diet on colonic cellular proliferation in the rat. Gut. 1992 Aug;33(8):1076–1079. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.8.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Englyst H. N., Kingman S. M., Cummings J. H. Classification and measurement of nutritionally important starch fractions. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1992 Oct;46 (Suppl 2):S33–S50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson L. R., Harris P. J. Studies on the role of specific dietary fibres in protection against colorectal cancer. Mutat Res. 1996 Feb 19;350(1):173–184. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(95)00105-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming S. E., Fitch M. D., De Vries S. The influence of dietary fiber on proliferation of intestinal mucosal cells in miniature swine may not be mediated primarily by fermentation. J Nutr. 1992 Apr;122(4):906–916. doi: 10.1093/jn/122.4.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folino M., McIntyre A., Young G. P. Dietary fibers differ in their effects on large bowel epithelial proliferation and fecal fermentation-dependent events in rats. J Nutr. 1995 Jun;125(6):1521–1528. doi: 10.1093/jn/125.6.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel W. L., Zhang W., Singh A., Klurfeld D. M., Don S., Sakata T., Modlin I., Rombeau J. L. Mediation of the trophic effects of short-chain fatty acids on the rat jejunum and colon. Gastroenterology. 1994 Feb;106(2):375–380. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90595-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs C. S., Giovannucci E. L., Colditz G. A., Hunter D. J., Stampfer M. J., Rosner B., Speizer F. E., Willett W. C. Dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. N Engl J Med. 1999 Jan 21;340(3):169–176. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901213400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee J. M., Faulks R. M., Johnson I. T. Physiological effects of retrograded, alpha-amylase-resistant cornstarch in rats. J Nutr. 1991 Jan;121(1):44–49. doi: 10.1093/jn/121.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson G. R., Willems A., Reading S., Collins M. D. Fermentation of non-digestible oligosaccharides by human colonic bacteria. Proc Nutr Soc. 1996 Nov;55(3):899–912. doi: 10.1079/pns19960087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad J. S., Mathers J. C. Large bowel fermentation in rats given diets containing raw peas (Pisum sativum). Br J Nutr. 1990 Sep;64(2):569–587. doi: 10.1079/bjn19900057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlad R. A., Ratcliffe B., Fordham J. P., Wright N. A. Does dietary fibre stimulate intestinal epithelial cell proliferation in germ free rats? Gut. 1989 Jun;30(6):820–825. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.6.820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs L. R. Relationship between dietary fiber and cancer: metabolic, physiologic, and cellular mechanisms. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986 Dec;183(3):299–310. doi: 10.3181/00379727-183-42423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstantakos A. K., Siu I. M., Pretlow T. G., Stellato T. A., Pretlow T. P. Human aberrant crypt foci with carcinoma in situ from a patient with sporadic colon cancer. Gastroenterology. 1996 Sep;111(3):772–777. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8780584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kritchevsky D. In vitro binding properties of dietary fibre. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1995 Oct;49 (Suppl 3):S113–S115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lajvardi A., Mazarin G. I., Gillespie M. B., Satchithanandam S., Calvert R. J. Starches of varied digestibilities differentially modify intestinal function in rats. J Nutr. 1993 Dec;123(12):2059–2066. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.12.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton J. R., Kurtz P. P. Relationship of colonic luminal short-chain fatty acids and pH to in vivo cell proliferation in rats. J Nutr. 1993 Sep;123(9):1522–1530. doi: 10.1093/jn/123.9.1522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlane G. T., Macfarlane S. Factors affecting fermentation reactions in the large bowel. Proc Nutr Soc. 1993 Aug;52(2):367–373. doi: 10.1079/pns19930072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciorowski K. G., Turner N. D., Lupton J. R., Chapkin R. S., Shermer C. L., Ha S. D., Ricke S. C. Diet and carcinogen alter the fecal microbial populations of rats. J Nutr. 1997 Mar;127(3):449–457. doi: 10.1093/jn/127.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBurney M. I., Thompson L. U. Fermentative characteristics of cereal brans and vegetable fibers. Nutr Cancer. 1990;13(4):271–280. doi: 10.1080/01635589009514069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre A., Gibson P. R., Young G. P. Butyrate production from dietary fibre and protection against large bowel cancer in a rat model. Gut. 1993 Mar;34(3):386–391. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntyre A., Young G. P., Taranto T., Gibson P. R., Ward P. B. Different fibers have different regional effects on luminal contents of rat colon. Gastroenterology. 1991 Nov;101(5):1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mortensen P. B., Hove H., Clausen M. R., Holtug K. Fermentation to short-chain fatty acids and lactate in human faecal batch cultures. Intra- and inter-individual variations versus variations caused by changes in fermented saccharides. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991 Dec;26(12):1285–1294. doi: 10.3109/00365529108998626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin P., Cassagnau E., Burg C., Patry Y., Vavasseur F., Harb J., Le Pendu J., Douillard J. Y., Galmiche J. P., Bornet F. An interleukin 2/sodium butyrate combination as immunotherapy for rat colon cancer peritoneal carcinomatosis. Gastroenterology. 1994 Dec;107(6):1697–1708. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pierre F., Perrin P., Bassonga E., Bornet F., Meflah K., Menanteau J. T cell status influences colon tumor occurrence in min mice fed short chain fructo-oligosaccharides as a diet supplement. Carcinogenesis. 1999 Oct;20(10):1953–1956. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.10.1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pories S. E., Ramchurren N., Summerhayes I., Steele G. Animal models for colon carcinogenesis. Arch Surg. 1993 Jun;128(6):647–653. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1993.01420180045009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretlow T. P., Barrow B. J., Ashton W. S., O'Riordan M. A., Pretlow T. G., Jurcisek J. A., Stellato T. A. Aberrant crypts: putative preneoplastic foci in human colonic mucosa. Cancer Res. 1991 Mar 1;51(5):1564–1567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pretlow T. P., O'Riordan M. A., Somich G. A., Amini S. B., Pretlow T. G. Aberrant crypts correlate with tumor incidence in F344 rats treated with azoxymethane and phytate. Carcinogenesis. 1992 Sep;13(9):1509–1512. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.9.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy B. S., Maruyama H. Effect of dietary fish oil on azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in male F344 rats. Cancer Res. 1986 Jul;46(7):3367–3370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto J., Nakaji S., Sugawara K., Iwane S., Munakata A. Comparison of resistant starch with cellulose diet on 1,2-dimethylhydrazine-induced colonic carcinogenesis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jan;110(1):116–120. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T. Effects of indigestible dietary bulk and short chain fatty acids on the tissue weight and epithelial cell proliferation rate of the digestive tract in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1986 Aug;32(4):355–362. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.32.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata T. Stimulatory effect of short-chain fatty acids on epithelial cell proliferation in the rat intestine: a possible explanation for trophic effects of fermentable fibre, gut microbes and luminal trophic factors. Br J Nutr. 1987 Jul;58(1):95–103. doi: 10.1079/bjn19870073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salyers A. A. Breakdown of polysaccharides by human intestinal bacteria. J Environ Pathol Toxicol Oncol. 1985 Jul;5(6):211–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W., Bartram H. P., Richter F. Role of short-chain fatty acids in the prevention of colorectal cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1995 Jul-Aug;31A(7-8):1077–1080. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00165-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W., Bartram P., Richter A., Richter F., Liepold H., Dusel G., Hofstetter G., Rüthlein J., Kasper H. Effect of short-chain fatty acids on the human colonic mucosa in vitro. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1992 Jan-Feb;16(1):43–48. doi: 10.1177/014860719201600143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheppach W., Fabian C., Sachs M., Kasper H. The effect of starch malabsorption on fecal short-chain fatty acid excretion in man. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1988 Aug;23(6):755–759. doi: 10.3109/00365528809093945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine K., Ushida Y., Kuhara T., Iigo M., Baba-Toriyama H., Moore M. A., Murakoshi M., Satomi Y., Nishino H., Kakizoe T. Inhibition of initiation and early stage development of aberrant crypt foci and enhanced natural killer activity in male rats administered bovine lactoferrin concomitantly with azoxymethane. Cancer Lett. 1997 Dec 23;121(2):211–216. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(97)00358-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivapurkar N., Tang Z. C., Alabaster O. The effect of high-risk and low-risk diets on aberrant crypt and colonic tumor formation in Fischer-344 rats. Carcinogenesis. 1992 May;13(5):887–890. doi: 10.1093/carcin/13.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen A. M. Starch and dietary fibre: their physiological and epidemiological interrelationships. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991 Jan;69(1):116–120. doi: 10.1139/y91-017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tudek B., Bird R. P., Bruce W. R. Foci of aberrant crypts in the colons of mice and rats exposed to carcinogens associated with foods. Cancer Res. 1989 Mar 1;49(5):1236–1240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varecha R., Barry J., Martingale J. Laboring to manage care. Bus Health. 1991 Aug;9(8):35, 38, 40-1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasan H. S., Goodlad R. A. Fibre-supplemented foods may damage your health. Lancet. 1996 Aug 3;348(9023):319–320. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)01401-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver G. A., Krause J. A., Miller T. L., Wolin M. J. Cornstarch fermentation by the colonic microbial community yields more butyrate than does cabbage fiber fermentation; cornstarch fermentation rates correlate negatively with methanogenesis. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992 Jan;55(1):70–77. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/55.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver G. A., Tangel C., Krause J. A., Alpern H. D., Jenkins P. L., Parfitt M. M., Stragand J. J. Dietary guar gum alters colonic microbial fermentation in azoxymethane-treated rats. J Nutr. 1996 Aug;126(8):1979–1991. doi: 10.1093/jn/126.8.1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteley L. O., Purdon M. P., Ridder G. M., Bertram T. A. The interactions of diet and colonic microflora in regulating colonic mucosal growth. Toxicol Pathol. 1996 May-Jun;24(3):305–314. doi: 10.1177/019262339602400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcox D. K., Higgins J., Bertram T. A. Colonic epithelial cell proliferation in a rat model of nongenotoxin-induced colonic neoplasia. Lab Invest. 1992 Sep;67(3):405–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada K., Yoshitake K., Sato M., Ahnen D. J. Proliferating cell nuclear antigen expression in normal, preneoplastic, and neoplastic colonic epithelium of the rat. Gastroenterology. 1992 Jul;103(1):160–167. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)91109-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young G. P., McIntyre A., Albert V., Folino M., Muir J. G., Gibson P. R. Wheat bran suppresses potato starch--potentiated colorectal tumorigenesis at the aberrant crypt stage in a rat model. Gastroenterology. 1996 Feb;110(2):508–514. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8566598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]