Abstract

BACKGROUND—Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is associated with changes in colonic motility which may contribute to the pain and diarrhoea associated with exacerbations of this disease. These changes may be mediated by prostaglandins which are increased in this condition. Increased expression of the inducible isoform of cyclo-oxygenase (COX-2) has been found in active IBD although its cellular distribution remains uncertain. AIMS—To evaluate the cellular distribution of COX-2 in active IBD. PATIENTS AND METHODS—Using reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction, in situ hybridisation, and immunohistochemistry, COX-2 expression was evaluated in 12 colectomy specimens from patients with active ulcerative colitis (UC), and six specimens from patients with Crohn's colitis that had failed medical therapy. Histologically normal colon was obtained from 12 patients having resection for colorectal neoplasia and evaluated as above, acting as control specimens. RESULTS—All specimens expressed COX-2 mRNA, with some 6-8-fold increase in inflamed tissues on densitometric analysis (both UC and Crohn's) compared with controls. In situ hybridisation localised this mRNA to myenteric neural cells, surrounding smooth muscle cells, and inflammatory cells of the lamina propria in the IBD specimens, with some weaker labelling seen in the epithelium. No COX-2 labelling was seen in normal tissues. Immunohistochemistry confirmed these sites of COX-2 expression in all inflamed specimens, with absence of immunoreactivity in control tissues. CONCLUSIONS—These findings provide the first evidence of COX-2 expression in neural cells of the myenteric plexus in active IBD which, via increased prostaglandin synthesis at this site, may contribute to the dysmotilty seen in this condition. Keywords: inducible cyclo-oxygenase; prostaglandins; myenteric plexus; inflammatory bowel disease

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (197.0 KB).

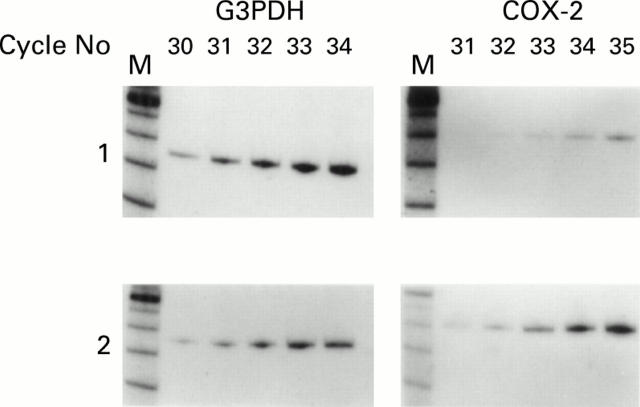

Figure 1 .

Example of kinetic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of COX-2 expression in normal (1) and ulcerative colitis (UC) (2) tissue. Densitometric analysis revealed greater expression (up to eightfold) of COX-2 product in 12/12 UC and 5/6 Crohn's specimens compared with normal tissue when standardised with respect to glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (G3PDH) levels. PCR cycle lengths: G3PDH 30-34, COX-2 31-35. M, DNA size markers from Gibco BRL, UK.

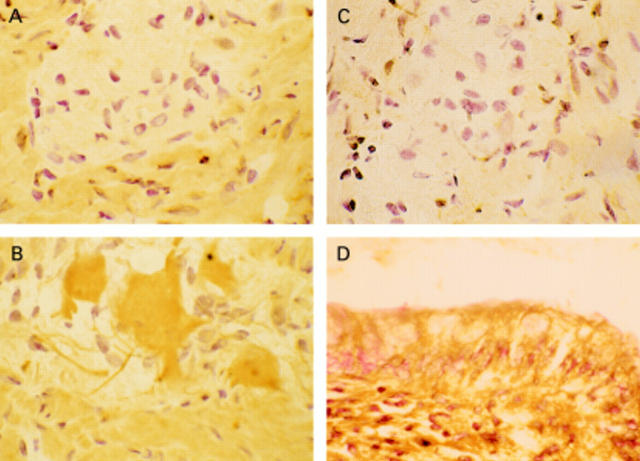

Figure 2 .

Example of COX-2 in situ hybridisation of surgical resection specimens. (A) Non-inflamed control tissue and antisense probe, with no labelling seen. (B) Diseased tissue (ulcerative colitis (UC) specimen) and sense probe—no labelling. (C) Diseased tissue (UC) and antisense probe with intense labelling of neural cells of the myenteric plexus. Similar results were obtained irrespective of the mode of inflammation—that is, in both UC and Crohn's specimens COX-2 mRNA was localised to the same cell types.

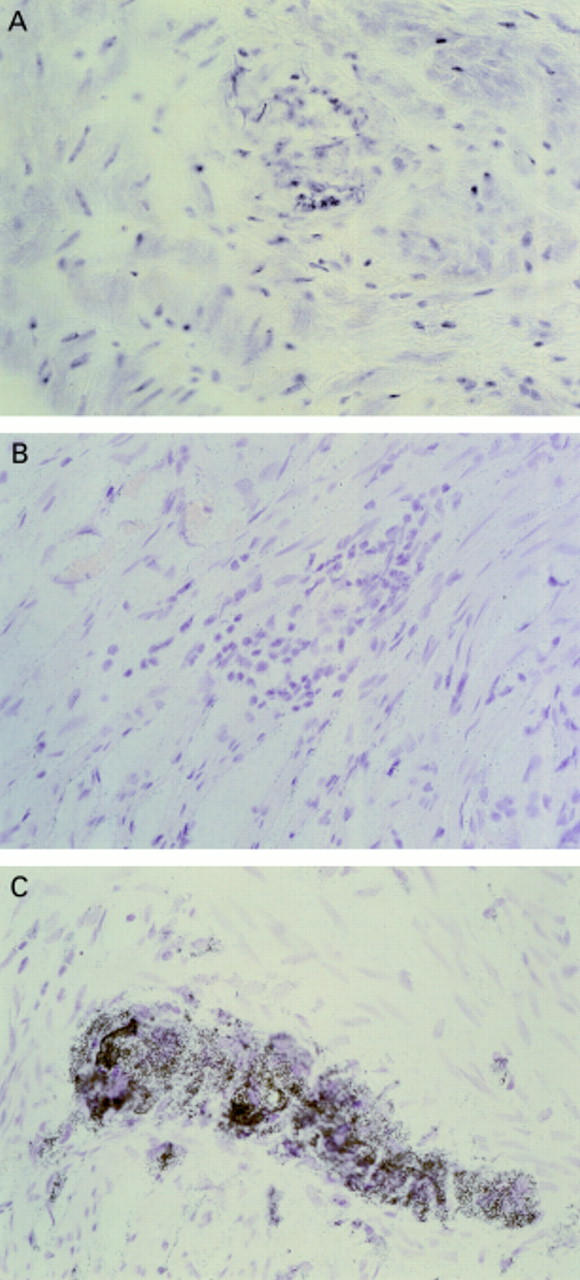

Figure 3 .

Example of immunolocalisation of COX-2. (A) Non-immune (control) serum-diseased tissue (ulcerative colitis (UC)), with no staining seen. (B) COX-2 labelling (brown stain) of neural cells of the myenteric plexus in diseased tissue (UC). (C) Absence of COX-2 labelling in myenteric plexus of normal tissue. (D) Labelling of epithelial cells with COX-2 in diseased tissue (UC).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Akai Y., Homma T., Burns K. D., Yasuda T., Badr K. F., Harris R. C. Mechanical stretch/relaxation of cultured rat mesangial cells induces protooncogenes and cyclooxygenase. Am J Physiol. 1994 Aug;267(2 Pt 1):C482–C490. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1994.267.2.C482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baccari M. C., Calamai F., Staderini G. Prostaglandin E2 modulates neurally induced nonadrenergic, noncholinergic gastric relaxations in the rabbit in vivo. Gastroenterology. 1996 Jan;110(1):129–138. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett A., Eley K. G., Stockley H. L. Modulation by prostaglandins of contractions in guinea-pig ileum. Prostaglandins. 1975 Mar;9(3):377–384. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(75)90142-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botella A., Delvaux M., Fioramonti J., Frexinos J., Bueno L. Stimulatory (EP1 and EP3) and inhibitory (EP2) prostaglandin E2 receptors in isolated ileal smooth muscle cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 1993 Jun 11;237(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90102-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chomczynski P., Sacchi N. Single-step method of RNA isolation by acid guanidinium thiocyanate-phenol-chloroform extraction. Anal Biochem. 1987 Apr;162(1):156–159. doi: 10.1006/abio.1987.9999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould S. R. Assay of prostaglandin-like substances in faeces and their measurement in ulcerative colitis. Prostaglandins. 1976 Mar;11(3):489–497. doi: 10.1016/0090-6980(76)90095-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossi L., McHugh K., Collins S. M. On the specificity of altered muscle function in experimental colitis in rats. Gastroenterology. 1993 Apr;104(4):1049–1056. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90273-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkey C. J., Karmeli F., Rachmilewitz D. Imbalance of prostacyclin and thromboxane synthesis in Crohn's disease. Gut. 1983 Oct;24(10):881–885. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.10.881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendel J., Nielsen O. H. Expression of cyclooxygenase-2 mRNA in active inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1997 Jul;92(7):1170–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt R. H., Dilawari J. B., Misiewicz J. J. The effect of intravenous prostaglandin F2 alpha and E2 on the motility of the sigmoid colon. Gut. 1975 Jan;16(1):47–49. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KERN F., Jr, ALMY T. P., ABBOT F. K., BOGDONOFF M. D. The motility of the distal colon in nonspecific ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1951 Nov;19(3):492–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R. A., Jones R. L., Wilson N. H. Characterization of receptors involved in the direct and indirect actions of prostaglandins E and I on the guinea-pig ileum. Br J Pharmacol. 1992 Feb;105(2):271–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masferrer J. L., Zweifel B. S., Manning P. T., Hauser S. D., Leahy K. M., Smith W. G., Isakson P. C., Seibert K. Selective inhibition of inducible cyclooxygenase 2 in vivo is antiinflammatory and nonulcerogenic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Apr 12;91(8):3228–3232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton S. J., Shorthouse M., Hunter J. O. Increased nitric oxide synthesis in ulcerative colitis. Lancet. 1993 Feb 20;341(8843):465–466. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90211-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mourelle M., Casellas F., Guarner F., Salas A., Riveros-Moreno V., Moncada S., Malagelada J. R. Induction of nitric oxide synthase in colonic smooth muscle from patients with toxic megacolon. Gastroenterology. 1995 Nov;109(5):1497–1502. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90636-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pairet M., Bouyssou T., Ruckebusch Y. Colonic formation of soft feces in rabbits: a role for endogenous prostaglandins. Am J Physiol. 1986 Mar;250(3 Pt 1):G302–G308. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1986.250.3.G302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy S. N., Bazzocchi G., Chan S., Akashi K., Villanueva-Meyer J., Yanni G., Mena I., Snape W. J., Jr Colonic motility and transit in health and ulcerative colitis. Gastroenterology. 1991 Nov;101(5):1289–1297. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90079-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter B. K., Asfaha S., Buret A., Sharkey K. A., Wallace J. L. Exacerbation of inflammation-associated colonic injury in rat through inhibition of cyclooxygenase-2. J Clin Invest. 1996 Nov 1;98(9):2076–2085. doi: 10.1172/JCI119013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rühl A., Berezin I., Collins S. M. Involvement of eicosanoids and macrophage-like cells in cytokine-mediated changes in rat myenteric nerves. Gastroenterology. 1995 Dec;109(6):1852–1862. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90752-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon P., Ligumsky M., Rachmilewitz D., Zor U. Role of prostaglandins in ulcerative colitis. Enhanced production during active disease and inhibition by sulfasalazine. Gastroenterology. 1978 Oct;75(4):638–640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer I. I., Kawka D. W., Schloemann S., Tessner T., Riehl T., Stenson W. F. Cyclooxygenase 2 is induced in colonic epithelial cells in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1998 Aug;115(2):297–306. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70196-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer I. I., Kawka D. W., Scott S., Weidner J. R., Mumford R. A., Riehl T. E., Stenson W. F. Expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase and nitrotyrosine in colonic epithelium in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 1996 Oct;111(4):871–885. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70055-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snape W. J., Jr, Matarazzo S. A., Cohen S. Abnormal gastrocolonic response in patients with ulcerative colitis. Gut. 1980 May;21(5):392–396. doi: 10.1136/gut.21.5.392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snape W. J., Jr, Williams R., Hyman P. E. Defect in colonic smooth muscle contraction in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Physiol. 1991 Dec;261(6 Pt 1):G987–G991. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1991.261.6.G987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]