Abstract

BACKGROUND—The involvement of nerves and calcium channels in the intestinal response to Clostridium difficile toxin A (luminal concentration 1 or 15 µg/ml) was studied in the small intestine of rats in vivo. METHODS—Inflammation was quantified by estimating myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the intestinal lumen, extravascular accumulation of Evan's blue (EB) in the intestine, and number of red blood cells (RBCs) in veins in histological sections. Intestinal damage was estimated using a histological grading system. In some experiments net fluid transport was recorded using a gravimetric technique. RESULTS—In acutely denervated intestines, toxin A caused marked destruction of the villi, increased luminal release of MPO activity, and augmentation of intestinal content of EB and venous RBCs. Denervating the intestine 3-4 weeks prior to the actual experiment prevented the development of villus damage and significantly decreased the number of RBCs in intestinal veins in experiments with a low toxin concentration, whereas no effect was demonstrated on luminal MPO activity. Using a high toxin concentration, chronic denervation decreased only the number of RBCs. Pretreatment with hexamethonium (low toxin concentration; acute denervation) attenuated the effect of toxin A on morphology, luminal MPO activity, and number of RBCs. Pretreatment with nifedipine (low toxin concentration; acute denervation) significantly decreased intestinal MPO activity and number of RBCs. Tissue accumulation of EB was not influenced by experimental manipulation. Net fluid transport was measured in experiments exposing the intestinal mucosa to a high toxin concentration. Fluid secretion caused by the toxin was significantly attenuated by intravenous hexamethonium whereas no effect was observed after administration of nifedipine or granisetron. CONCLUSIONS—At a low toxin concentration, intramural reflexes are involved in the inflammatory response whereas axon reflexes contribute to tissue damage. At a high toxin concentration no nervous involvement in the toxin A response was demonstrated except for fluid secretion evoked by the toxin. Keywords: cholera toxin; enteric nervous system; 5-hydroxytryptamine; myeloperoxidase; red blood cells

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (163.9 KB).

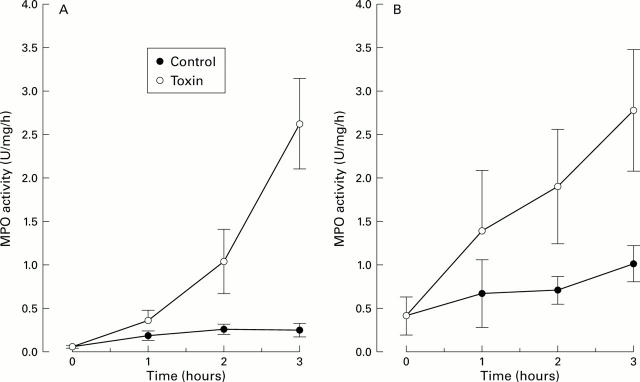

Figure 1 .

Effect of Clostridium difficile toxin A (1 µg/ml physiological saline) on myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity in the intestinal lumen at various times after exposing one segment to the toxin. A control segment was only exposed to physiological saline. (A) Experiments (n=6) in which the intestines were acutely denervated by cutting the periarterial nerves. (B) Results from the experiments (n=5) in which the intestines were denervated 4-6 weeks prior to the experiments ("chronic denervation"). Values are given as mean (SEM).

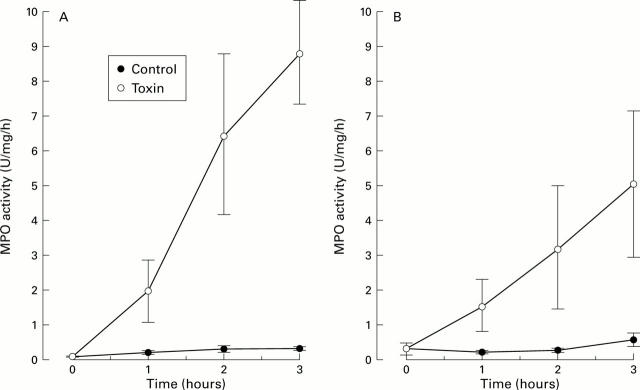

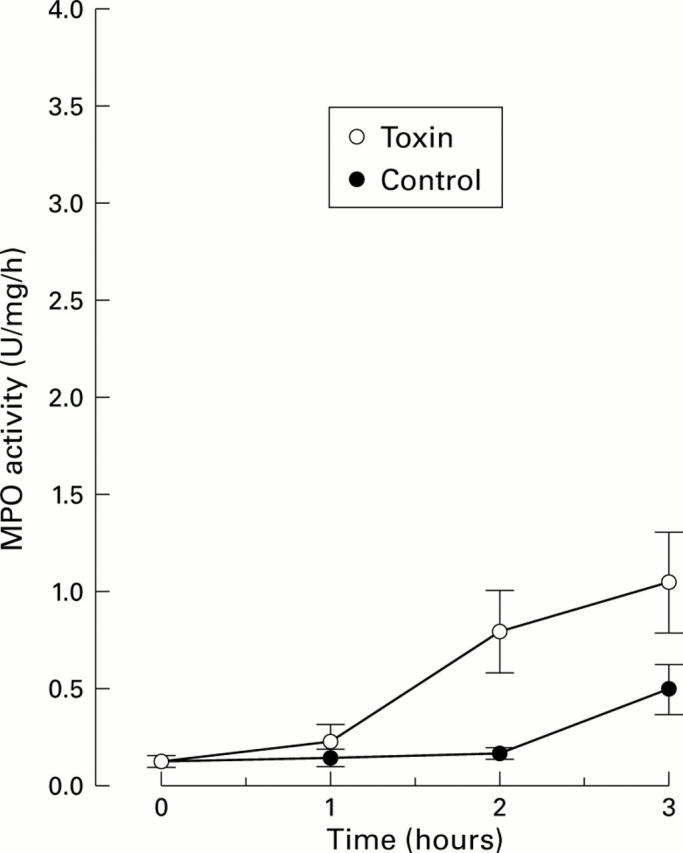

Figure 2 .

Effect of Clostridium difficile toxin A (15 µg/ml physiological saline) on myeoloperoxidase activity (MPO) in the intestinal lumen at various times after exposing one segment to the toxin. A control segment was only exposed to physiological saline. (A) Experiments (n=6) in which the intestines were acutely denervated by cutting the periarterial nerves. (B) Results from experiments (n=5) in which the intestines were denervated 4-6 weeks prior to the experiments ("chronic denervation"). Values are given as mean (SEM).

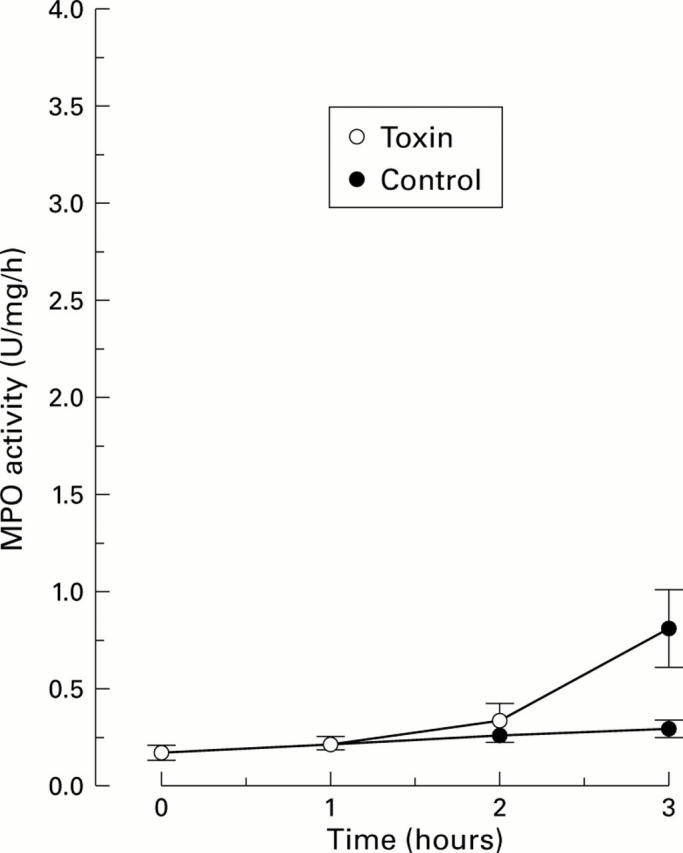

Figure 3 .

Effect of Clostridium difficile toxin A (1 µg/ml physiological saline) on myeoloperoxidase activity (MPO) in the lumen of acutely denervated intestinal segments of animals pretreated with hexamethonium, a nicotinic receptor blocker. MPO activity at various times after exposing one segment to the toxin is shown. A control segment was only exposed to physiological saline. MPO activity response to the toxin was markedly attenuated by the drug (compare figs 1 and 3). Values are mean (SEM); n=5.

Figure 4 .

Effect of Clostridium difficile toxin A (1 µg/ml physiological saline) on myeoloperoxidase activity (MPO) in the intestinal lumen in animals pretreated with nifedipine, a blocker of calcium channels of the L-type. Intestinal segments were acutely denervated. MPO activity at various times after exposing one segment to the toxin is shown. A control segment was only exposed to physiological saline. MPO activity response to the toxin was markedly attenuated by the drug (compare figs 1 and 4). Values are mean (SEM); n=6.

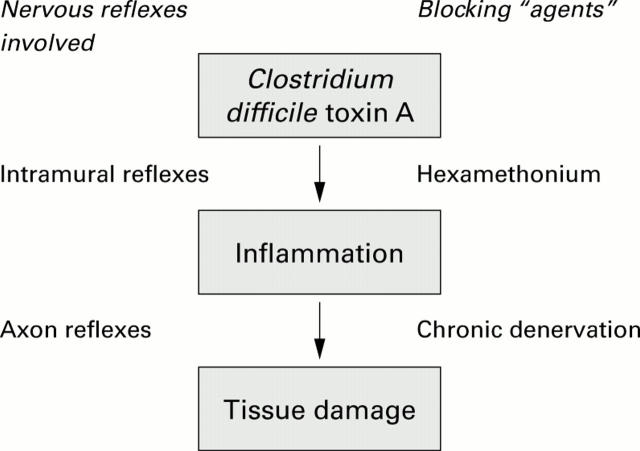

Figure 5 .

Hypothetical model based on the findings of the present study. Nerves participate both in the development of the inflammatory response and in the events leading to tissue damage, at least when toxin concentrations are not too high. The results of the present study suggest that an intramural reflex(es) is involved in the toxin response leading to inflammation whereas an axon reflex(es) participates in the development of tissue damage.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Arnon S. S., Mills D. C., Day P. A., Henrickson R. V., Sullivan N. M., Wilkins T. D. Rapid death of infant rhesus monkeys injected with Clostridium difficile toxins A and B: physiologic and pathologic basis. J Pediatr. 1984 Jan;104(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(84)80585-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beubler E., Horina G. 5-HT2 and 5-HT3 receptor subtypes mediate cholera toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion in the rat. Gastroenterology. 1990 Jul;99(1):83–89. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)91233-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein J. C., Furness J. B., Costa M. Sources of excitatory synaptic inputs to neurochemically identified submucous neurons of guinea-pig small intestine. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1987 Jan;18(1):83–91. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(87)90137-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley P. P., Priebat D. A., Christensen R. D., Rothstein G. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation: estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J Invest Dermatol. 1982 Mar;78(3):206–209. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsson I. Enteric nerves mediate the fluid secretory response due to Salmonella typhimurium R5 infection in the rat small intestine. Acta Physiol Scand. 1987 Dec;131(4):609–617. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsson I., Sjöqvist A., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Mechanisms underlying the intestinal fluid secretion evoked by nociceptive serosal stimulation of the rat. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1985 Feb;328(4):439–445. doi: 10.1007/BF00692913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunsson I., Sjöqvist A., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Mechanisms underlying the small intestinal fluid secretion caused by arachidonic acid, prostaglandin E1 and prostaglandin E2 in the rat in vivo. Acta Physiol Scand. 1987 Aug;130(4):633–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassuto J., Jodal M., Lundgren O. The effect of nicotinic and muscarinic receptor blockade on cholera toxin induced intestinal secretion in rats and cats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1982 Apr;114(4):573–577. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1982.tb07026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassuto J., Jodal M., Tuttle R., Lundgren O. 5-hydroxytryptamine and cholera secretion. Physiological and pharmacological studies in cats and rats. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1982 Aug;17(5):695–703. doi: 10.3109/00365528209181081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassuto J., Jodal M., Tuttle R., Lundgren O. On the role of intramural nerves in the pathogenesis of cholera toxin-induced intestinal secretion. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1981 Apr;16(3):377–384. doi: 10.3109/00365528109181984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagliuolo I., LaMont J. T., Letourneau R., Kelly C., O'Keane J. C., Jaffer A., Theoharides T. C., Pothoulakis C. Neuronal involvement in the intestinal effects of Clostridium difficile toxin A and Vibrio cholerae enterotoxin in rat ileum. Gastroenterology. 1994 Sep;107(3):657–665. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(94)90112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund S., Jodal M., Lundgren O. The enteric nervous system participates in the secretory response to the heat stable enterotoxins of Escherichia coli in rats and cats. Neuroscience. 1985 Feb;14(2):673–681. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90318-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentini C., Thelestam M. Clostridium difficile toxin A and its effects on cells. Toxicon. 1991;29(6):543–567. doi: 10.1016/0041-0101(91)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamse R., Holzer P., Lembeck F. Decrease of substance P in primary afferent neurones and impairment of neurogenic plasma extravasation by capsaicin. Br J Pharmacol. 1980 Feb;68(2):207–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb10409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzer P. Local effector functions of capsaicin-sensitive sensory nerve endings: involvement of tachykinins, calcitonin gene-related peptide and other neuropeptides. Neuroscience. 1988 Mar;24(3):739–768. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90064-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaup E. A., Timar Peregrin A., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Nervous control of alkaline secretion in the duodenum as studied by the use of cholera toxin in the anaesthetized rat. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998 Feb;162(2):165–174. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.0290f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodal M., Holmgren S., Lundgren O., Sjöqvist A. Involvement of the myenteric plexus in the cholera toxin-induced net fluid secretion in the rat small intestine. Gastroenterology. 1993 Nov;105(5):1286–1293. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90130-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jodal M., Wingren U., Jansson M., Heidemann M., Lundgren O. Nerve involvement in fluid transport in the inflamed rat jejunum. Gut. 1993 Nov;34(11):1526–1530. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.11.1526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlström L., Cassuto J., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Involvement of the enteric nervous system in the intestinal secretion induced by sodium deoxycholate and sodium ricinoleate. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1986 Apr;21(3):331–340. doi: 10.3109/00365528609003083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlström L., Cassuto J., Jodal M., Lundgren O. The importance of the enteric nervous system for the bile-salt-induced secretion in the small intestine of the rat. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1983 Jan;18(1):117–123. doi: 10.3109/00365528309181570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lum H., Malik A. B. Mechanisms of increased endothelial permeability. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996 Jul;74(7):787–800. doi: 10.1139/y96-081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellgård P., Jönsson A., Bojö L., Tarnow P., Cassuto J. Small-bowel obstruction and the effects of lidocaine, atropine and hexamethonium on inflammation and fluid losses. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1996 Mar;40(3):287–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-6576.1996.tb04435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peregrin A. T., Ahlman H., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Involvement of serotonin and calcium channels in the intestinal fluid secretion evoked by bile salt and cholera toxin. Br J Pharmacol. 1999 Jun;127(4):887–894. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pothoulakis Charalabos, Castagliuolo Ignazio, LaMont J. Thomas. Nerves and Intestinal Mast Cells Modulate Responses to Enterotoxins. News Physiol Sci. 1998 Apr;13(NaN):58–63. doi: 10.1152/physiologyonline.1998.13.2.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riegler M., Sedivy R., Pothoulakis C., Hamilton G., Zacherl J., Bischof G., Cosentini E., Feil W., Schiessel R., LaMont J. T. Clostridium difficile toxin B is more potent than toxin A in damaging human colonic epithelium in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1995 May;95(5):2004–2011. doi: 10.1172/JCI117885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rózsa Z., Sharkey K. A., Jancsó G., Varró V. Evidence for a role of capsaicin-sensitive mucosal afferent nerves in the regulation of mesenteric blood flow in the dog. Gastroenterology. 1986 Apr;90(4):906–910. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(86)90866-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schierwagen C., Bylund-Fellenius A. C., Lundberg C. Improved method for quantification of tissue PMN accumulation measured by myeloperoxidase activity. J Pharmacol Methods. 1990 May;23(3):179–186. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(90)90061-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöqvist A., Cassuto J., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Actions of serotonin antagonists on cholera-toxin-induced intestinal fluid secretion. Acta Physiol Scand. 1992 Jul;145(3):229–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1992.tb09360.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sjöqvist A. Interaction between antisecretory opioid and sympathetic mechanisms in the rat small intestine. Acta Physiol Scand. 1991 May;142(1):127–132. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1991.tb09137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timar Peregrin A., Ahlman H., Jodal M., Lundgren O. Effects of calcium channel blockade on intestinal fluid secretion: sites of action. Acta Physiol Scand. 1997 Aug;160(4):379–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1997.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timar Peregrin A., Svensson M., Ahlman H., Jodal M., Lundgren O. The effects on net fluid transport of noxious stimulation of jejunal mucosa in anaesthetized rats. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999 May;166(1):55–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00550.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsien R. W., Lipscombe D., Madison D. V., Bley K. R., Fox A. P. Multiple types of neuronal calcium channels and their selective modulation. Trends Neurosci. 1988 Oct;11(10):431–438. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(88)90194-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Eichel-Streiber C., Harperath U., Bosse D., Hadding U. Purification of two high molecular weight toxins of Clostridium difficile which are antigenically related. Microb Pathog. 1987 May;2(5):307–318. doi: 10.1016/0882-4010(87)90073-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]