Abstract

Background—Study of the vascular response to stent implantation has been hampered by difficulties in sectioning metal and tissue without distortion of the tissue stent interface. The metal is often removed before histochemical processing, causing a loss of arterial architecture. Histological and immunohistochemical sections should be 5 µm with an intact tissue stent interface. Objectives—To identify the most suitable cutting and grinding equipment, embedding resin, and slides for producing thin sections of stented arteries with the stent wires in situ for histological, immunohistochemical, and transmission electron microscopic (TEM) analyses. Methods—20 balloon stainless steel stents were implanted in the coronary arteries of 10 pigs. Twenty eight days later the stented arterial segments were excised, formalin fixed, embedded in five different resins (Epon 812, LR white, T9100, T8100, and JB4), and sectioned with two different high speed saws and a grinder for histological, immunohistochemical, and TEM analyses. Five stented human arteries were obtained at necropsy and processed using the best of the reported methods. Results—The Isomet precision saw and grinder/polisher unit reliably produced 5 µm sections with most embedding resins; minimum section thickness with the horizontal saw was 400 µm. Resin T8100, a glycol methacrylate, enabled satisfactory sectioning, grinding, and histological (toluidine blue, haematoxylin and eosin, and trichromatic and polychromatic stains) and immunohistochemical analyses (α smooth muscle actin, von Willebrand factor, vimentin, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, and CD68 (mac 387)). T9100 and T8100 embedded stented sections were suitable for ultrastructural examination with TEM. Stented human arterial sections showed preserved arterial architecture with the struts in situ. Conclusion—This study identified the optimal methods for embedding, sawing, grinding, and slide mounting of stented arteries to achieve 5 µm sections with an intact tissue metal interface, excellent surface qualities, histological and immunohistochemical staining properties, and suitability for TEM examination. The technique is applicable to experimental and clinical specimens. Keywords: stents; resin; histology; immunohistochemistry; transmission electron microscopy

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (301.9 KB).

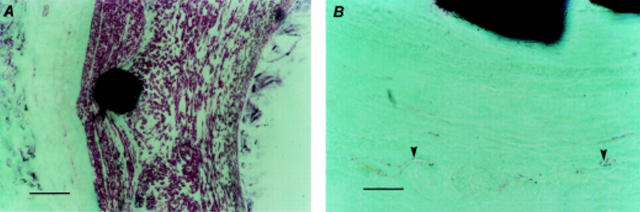

Figure 1 .

Histological staining of stented arterial sections. (A) Haematoxylin and eosin stained section (scale bar = 500 µm) showing preserved arterial wall architecture and stent struts in situ; and (B) at higher magnification (scale bar = 100 µm) with an intact internal elastic lamina (arrowheads). (C) Toluidine blue stained section (scale bar = 100 µm) showing varying spatial orientation of cells within the neointimal layer. (D) Trichromatic stained section (scale bar = 100 µm) showing struts in situ, preserved arterial architecture, and an intact internal elastic lamina (arrowheads); and (E) at higher magnification (scale bar = 50 µm) showing cells around the strut arranged in clusters, unlike cells nearer the lumen. (F) Haematoxylin stained section (scale bar = 5 µm) showing an intact tissue metal interface with neointimal cells around the strut arranged in clusters.

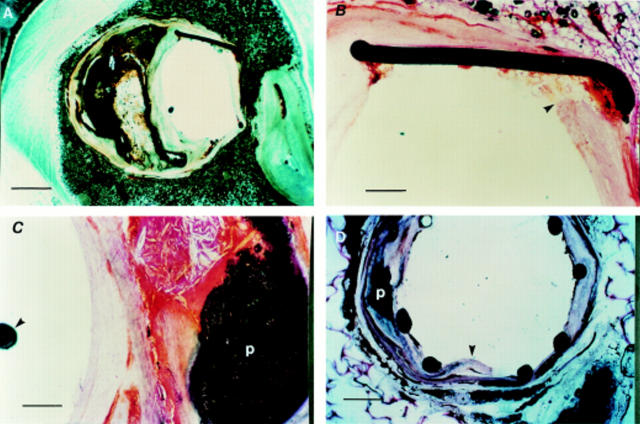

Figure 2 .

Immunohistochemical staining of stented arterial sections. (A) α Smooth muscle actin staining (scale bar = 100 µm): α smooth muscle actin positive cells are stained red (New Fuchsin Red), the counterstain is methyl green. All cells within the neointima, with distinctly differing spatial orientation, and media are positive for a smooth muscle actin. (B) von Willebrand Factor staining (scale bar = 50 µm): endothelium (arrowheads) of the vasa vasorum of the adventitia is stained red (New Fuchsin Red), the counterstain is methyl green.

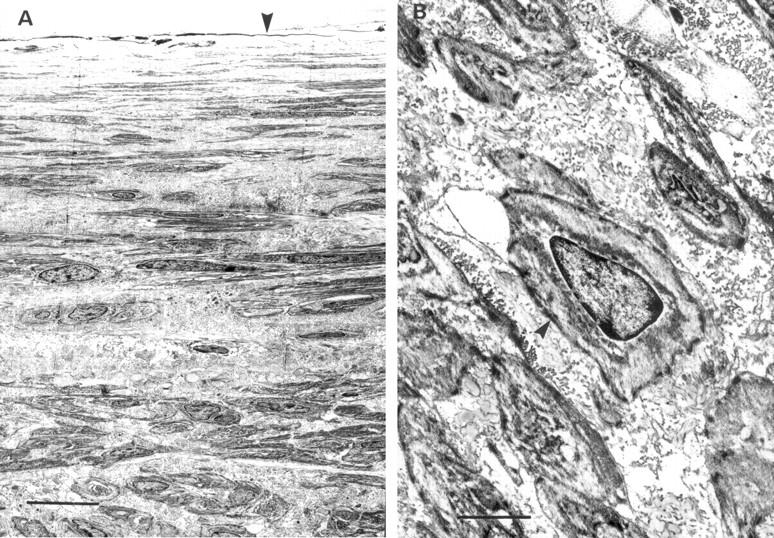

Figure 3 .

Transmission electron micrographs of stented coronary artery sections. (A) Neointimal layer 28 days after stenting with abundant extracellular matrix and interspersed smooth muscle cells (scale bar = 0.5 µm) arranged in distinctly different spatial orientation. Arrowhead indicates the luminal surface. (B) Phenotype of the neointimal cells is confirmed as smooth muscle cells (scale bar = 0.18 µm). Note characteristic cytoplasmic motor regions of these cells (arrowhead).

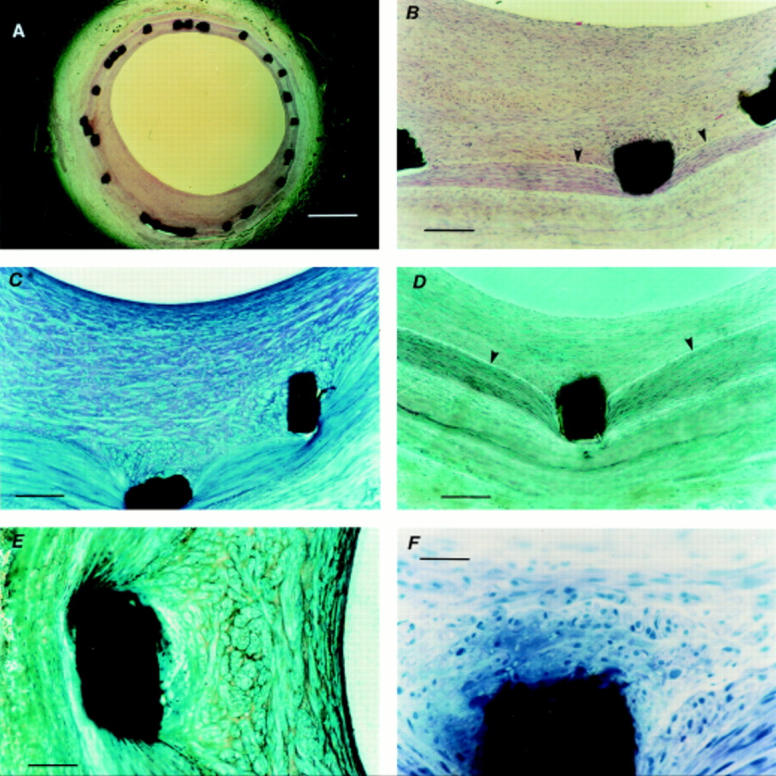

Figure 4 .

Stented human arterial sections. (A) Stented left anterior descending artery (LAD) section (scale bar = 500 µm), without histological staining showing preserved arterial wall architecture with an eccentric calcified plaque and stent struts in situ. (B) Haematoxylin and eosin stained section (scale bar = 50 µm) showing the stent strut embedded into relatively normal part of the arterial wall (arrowhead). (C) Haematoxylin and eosin staining showing complex calcified plaque (p) with an intact capsule (scale bar = 50 µm). Note position of the guidewire (arrowhead) in the arterial lumen. (D) Unstained LAD section, obtained at necropsy from another patient, showing preserved arterial architecture and stent struts in situ. The dissection (arrowhead) mostly involves the relatively normal area of the arterial wall. Note the adjacent calcified plaque (p).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barth K. H., Virmani R., Strecker E. P., Savin M. A., Lindisch D., Matsumoto A. H., Teitelbaum G. P. Flexible tantalum stents implanted in aortas and iliac arteries: effects in normal canines. Radiology. 1990 Apr;175(1):91–96. doi: 10.1148/radiology.175.1.2315508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsboom P. C., Wolfs B. H., Leydsman H., Doorn N., ten Bosch J. J., Liem K. G. A machine for sawing 80-micrometer slices of carious enamel. Stain Technol. 1987 Mar;62(2):119–125. doi: 10.3109/10520298709107978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio V. L., Pignoloni P., Baroni C. D. Immunohistology of bone marrow: a modified method of glycol-methacrylate embedding. Histopathology. 1991 Jan;18(1):37–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1991.tb00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bär F. W., van Oppen J., de Swart H., van Ommen V., Havenith M., Daemen M., Leenders P., van der Veen F. H., van Lankveld M., Verduin M. Percutaneous implantation of a new intracoronary stent in pigs. Am Heart J. 1991 Dec;122(6):1532–1541. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90268-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey T. T., Cousar J. B., Collins R. D. A simplified plastic embedding and immunohistologic technique for immunophenotypic analysis of human hematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Am J Pathol. 1988 May;131(2):183–189. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crochet D., Grossetête R., Bach-Lijour B., Sagan C., Lecomte E., Leurent B., Brunel P., Le Nihouannen J. C. Plasma treatment effects on the tantalum Strecker stent implanted in femoral arteries of sheep. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1994 Sep-Oct;17(5):285–291. doi: 10.1007/BF00192453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donath K., Breuner G. A method for the study of undecalcified bones and teeth with attached soft tissues. The Säge-Schliff (sawing and grinding) technique. J Oral Pathol. 1982 Aug;11(4):318–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0714.1982.tb00172.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman D. L., Leon M. B., Baim D. S., Schatz R. A., Savage M. P., Penn I., Detre K., Veltri L., Ricci D., Nobuyoshi M. A randomized comparison of coronary-stent placement and balloon angioplasty in the treatment of coronary artery disease. Stent Restenosis Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1994 Aug 25;331(8):496–501. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves P. H., Banning A. P., Penny W. J., Lewis M. J., Cheadle H. A., Newby A. C. Kinetics of smooth muscle cell proliferation and intimal thickening in a pig carotid model of balloon injury. Atherosclerosis. 1995 Sep;117(1):83–96. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(95)05562-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves P. H., Banning A. P., Penny W. J., Newby A. C., Cheadle H. A., Lewis M. J. The effects of exogenous nitric oxide on smooth muscle cell proliferation following porcine carotid angioplasty. Cardiovasc Res. 1995 Jul;30(1):87–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunn J., Holt C. M., Francis S. E., Shepherd L., Grohmann M., Newman C. M., Crossman D. C., Cumberland D. C. The effect of oligonucleotides to c-myb on vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointima formation after porcine coronary angioplasty. Circ Res. 1997 Apr;80(4):520–531. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.4.520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehrlein C., Gollan C., Dönges K., Metz J., Riessen R., Fehsenfeld P., von Hodenberg E., Kübler W. Low-dose radioactive endovascular stents prevent smooth muscle cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia in rabbits. Circulation. 1995 Sep 15;92(6):1570–1575. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.6.1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird J. R., Carter A. J., Kufs W. M., Hoopes T. G., Farb A., Nott S. H., Fischell R. E., Fischell D. R., Virmani R., Fischell T. A. Inhibition of neointimal proliferation with low-dose irradiation from a beta-particle-emitting stent. Circulation. 1996 Feb 1;93(3):529–536. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmaz J. C., Windeler S. A., Garcia F., Tio F. O., Sibbitt R. R., Reuter S. R. Atherosclerotic rabbit aortas: expandable intraluminal grafting. Radiology. 1986 Sep;160(3):723–726. doi: 10.1148/radiology.160.3.2942964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugliarello M. C., Vittur F., de Bernard B., Bonucci E., Ascenzi A. Analysis of bone composition at the microscopic level. Calcif Tissue Res. 1973;12(3):209–216. doi: 10.1007/BF02013735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson K. A., Roubin G., King S., Siegel R., Rodgers G., Apkarian R. P. Correlated microscopic observations of arterial responses to intravascular stenting. Scanning Microsc. 1989 Jun;3(2):665–679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoian E. C., King S. B., 3rd Intravascular stents, intimal proliferation and restenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Mar 15;19(4):877–879. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90535-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schatz R. A., Palmaz J. C., Tio F. O., Garcia F., Garcia O., Reuter S. R. Balloon-expandable intracoronary stents in the adult dog. Circulation. 1987 Aug;76(2):450–457. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.76.2.450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz R. S., Huber K. C., Murphy J. G., Edwards W. D., Camrud A. R., Vlietstra R. E., Holmes D. R. Restenosis and the proportional neointimal response to coronary artery injury: results in a porcine model. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Feb;19(2):267–274. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90476-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serruys P. W., de Jaegere P., Kiemeneij F., Macaya C., Rutsch W., Heyndrickx G., Emanuelsson H., Marco J., Legrand V., Materne P. A comparison of balloon-expandable-stent implantation with balloon angioplasty in patients with coronary artery disease. Benestent Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994 Aug 25;331(8):489–495. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408253310801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Fard A., Galeo A., Hutchinson H. G., Vermani P., Dodge G. R., Hall D. J., Shaheen F., Zalewski A. Transcatheter delivery of c-myc antisense oligomers reduces neointimal formation in a porcine model of coronary artery balloon injury. Circulation. 1994 Aug;90(2):944–951. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.2.944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Pieniek M., Fard A., O'Brien J., Mannion J. D., Zalewski A. Adventitial remodeling after coronary arterial injury. Circulation. 1996 Jan 15;93(2):340–348. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigwart U., Puel J., Mirkovitch V., Joffre F., Kappenberger L. Intravascular stents to prevent occlusion and restenosis after transluminal angioplasty. N Engl J Med. 1987 Mar 19;316(12):701–706. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198703193161201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamiya H., Batsford S. R., Tokunaga J., Vogt A. Immunohistological staining of antigens on semithin sections of specimens embedded in plastic (GMA-Quetol 523). J Immunol Methods. 1979;30(3):277–288. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(79)90102-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamiya H., Bodemer W., Vogt A. Masking of protein antigen by modification of amino groups with carbobenzoxychloride (benzyl chloroformate) and demasking by treatment with nonspecific protease. J Histochem Cytochem. 1978 Nov;26(11):914–920. doi: 10.1177/26.11.82572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tominaga R., Kambic H. E., Emoto H., Harasaki H., Sutton C., Hollman J. Effects of design geometry of intravascular endoprostheses on stenosis rate in normal rabbits. Am Heart J. 1992 Jan;123(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90742-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Giessen W. J., Serruys P. W., van Beusekom H. M., van Woerkens L. J., van Loon H., Soei L. K., Strauss B. H., Beatt K. J., Verdouw P. D. Coronary stenting with a new, radiopaque, balloon-expandable endoprosthesis in pigs. Circulation. 1991 May;83(5):1788–1798. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.5.1788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]