Abstract

Objective—To investigate the possible coexistence of mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations in patients with β myosin heavy chain (βMHC) linked hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) who develop congestive heart failure. Design—Molecular analysis of βMHC and mtDNA gene defects in patients with HCM. Setting—Cardiovascular molecular diagnostic and heart transplantation reference centre in north Italy. Patients—Four patients with HCM who underwent heart transplantation for end stage heart failure, and after pedigree analysis of 60 relatives, eight additional affected patients and 27 unaffected relatives. A total of 111 unrelated healthy adult volunteers served as controls. Disease controls included an additional 27 patients with HCM and 102 with dilated cardiomyopathy. Intervention—Molecular analysis of DNA from myocardial and skeletal muscle tissue and from peripheral blood specimens. Main outcome measures—Screening for mutations in βMHC (exons 3-23) and mtDNA tRNA (n = 22) genes with denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis or single strand conformational polymorphism followed by automated DNA sequencing. Results—One proband (kindred A) (plus seven affected relatives) had arginine 249 glutamine (Arg249Gln) βMHC and heteroplasmic mtDNA tRNAIle A4300G mutations. Another unrelated patient (kindred B) with sporadic HCM had identical mutations. The remaining two patients (kindred C), a mother and son, had a novel βMHC mutation (lysine 450 glutamic acid) (Lys450Glu) and a heteroplasmic missense (T9957C, phenylalanine (Phe)->leucine (Leu)) mtDNA mutation in subunit III of the cytochrome C oxidase gene. The amount of mutant mtDNA was higher in the myocardium than in skeletal muscle or peripheral blood and in affected patients than in asymptomatic relatives. Mutations were absent in the controls. Pathological and biochemical characteristics of patients with mutations Arg249Gln plus A4300G (kindreds A and B) were identical, but different from those of the two patients with Lys450Glu plus T9957C(Phe->Leu) mutations (kindred C). Cytochrome C oxidase activity and histoenzymatic staining were severely decreased in the two patients in kindreds A and B, but were unaffected in the two in kindred C. Conclusions—βMHC gene and mtDNA mutations may coexist in patients with HCM and end stage congestive heart failure. Although βMHC gene mutations seem to be the true determinants of HCM, both mtDNA mutations in these patients have known prerequisites for pathogenicity. Coexistence of other genetic abnormalities in βMHC linked HCM, such as mtDNA mutations, may contribute to variable phenotypic expression and explain the heterogeneous behaviour of HCM. Keywords: β myosin heavy chain; mitochondrial DNA; hypertrophic cardiomyopathy; oxidative phosphorylation; congestive heart failure

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (333.7 KB).

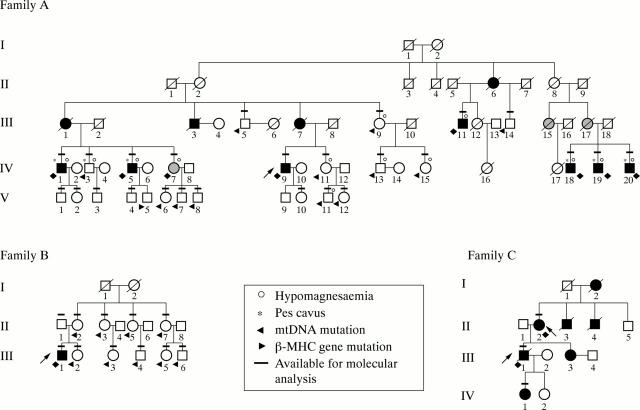

Figure 1 .

Three pedigrees showing familial (A and C) and non-familial (B) hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) with late dilating congestive evolution. Solid symbols indicate affected individuals, both symptomatic and asymptomatic. Horizontal bars indicate individuals whose DNA was tested. Probands are indicated by arrows. Family A. I: subjects 1 and 2 died of non-cardiac causes in old age; II: subjects 1, 2, 5, and 7-9 died of non-cardiac causes, subjects 3 and 4 may possibly have died of non-cardiac causes, and subject 6 died suddenly of heart disease at 48 years of age; III: subjects 1, 3, and 7 were clinically documented by medical records as affected by cardiomyopathy and died of congestive heart failure (III-1 and III-3) and of sudden death (III-7) at 47, 50, and 48 years of age, respectively; subjects 15 and 17 were probably affected by heart disease but were referred to as having died of non-cardiac causes; subjects 2, 6, 8, 10, 12, 16, and 18 died of non-cardiac causes in old age; IV: subject 16 died of hydrocephalia/ventricular malformation at 7 years of age; subject 17 died of unspecified malformations at 12 years of age. (Table 1 summarises information about other family members.) Family B. I: subjects 1 and 2 died of non-cardiac causes in old age. (Table 1 summarises information about other family members.) Family C. I: subject 1 died of non-cardiac causes in old age; subject 2 died of heart disease with congestive heart failure at 59 years of age; II: subject 3 died of "cardiomyopathy" with congestive heart failure at 18 years of age; subject 4 died suddenly at 32 years of age; III: subject 1 died after heart transplantation at 31 years of age; subject 3 had HCM with supraventricular arrhythmias; IV: subject 1 (8 years old) is affected by HCM.

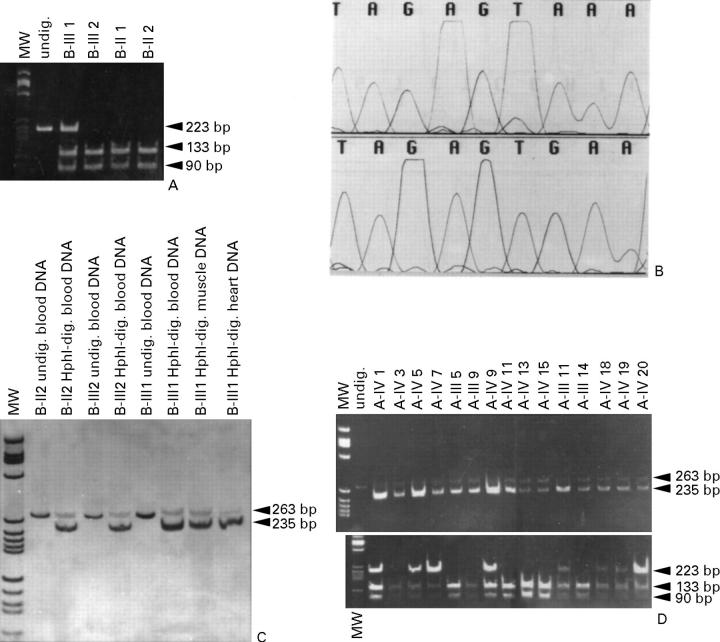

Figure 2 .

(A) Family B. PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses with EcoRI of the βMHC gene region encompassing exon 9: molecular weight (MW) marker pBR 322 digested with HaeIII. EcoRI digestion of the mutant DNA produces a 223 base pair (bp) fragment, which corresponds to the mutated, uncut allele, and two fragments of 133 and 90 bp, which correspond to the mutated allele. (B) Family A. Top: wild-type DNA sequence 4294-4302 (TAGAGTAAA) of the 5' region of mtDNA tRNAIle from a normal control. Bottom: the A4300G (TAGAGTGAA) transition. (C) Family B. PCR and RFLP analyses using HphI to assess heteroplasmy of A4300G. MW marker pBR 322 digested with HaeIII. HphI digestion of the PCR fragment generated by the mismatch primer (A4297G) in combination with mutation A4300G produces two fragments of 235 and 28 bp (the latter is not visible). The mutation is almost homoplasmic in heart mtDNA of proband III-1. (D) Family A-III and IV, live patients. Top: HphI digestion to assess heteroplasmy of the mtDNA A4300G transition. Severely affected patients IV-1, 5, and 9 have a very high amount of mutant DNA. Bottom: EcoRI digestion of the exon 9 region of βMHC. The mutation co-segregates with the phenotype, with the single exception of IV-7, for whom there was no echocardiographic evidence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and only negative T waves in V1-V3 were seen on the ECG.

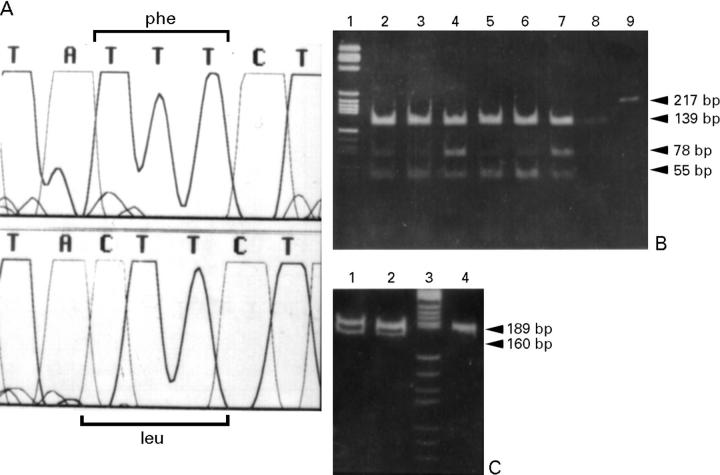

Figure 3 .

(A) Family C. Top: 9955-9961 wild-type sequence (TATTTCT) of the mtDNA COXIII gene from a normal control. Bottom: non-conservative T-C transition at position 9957 (TACTTCT) causes a Phe-Leu change. (B) PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analyses using RsaI digestion to detect heteroplasmy of mutation T9957C in the COX III gene; RsaI digestion of wild-type DNA produces two fragments of 139 and 78 bp, while RsaI digestion of the PCR product generated by the mismatch primer, in combination with the mutation, produces two further fragments of 55 and of 23 bp (the latter is not shown). Lane 1: molecular weight marker PBR 322 digested with HaeIII; lanes 2, 3, and 4: patient II-2, heart, muscle, and blood specimens of patient II-2; lanes 5, 6, and 7: patient III-1 heart, muscle, and blood specimens of patient III-1; lane 8: normal control; lane 9: undigested control. (C) PCR and RFLP analyses with AvaI of the βMHC gene region encompassing exon 14. Lane 3: MW marker pBR 322 digested with HaeIII. AvaI digestion of the mutant DNA amplified with a forward mismatch primer (5' ACG CGC ATC AAT GCC ACC CTG GAG CC '3, mismatch underlined) produces a 189 bp fragment, which corresponds to the wild-type, uncut allele, and two fragments of 160 and 29 bp (the latter is not seen), which correspond to the mutated allele. Lanes 1 and 2: patients II-2 and III-1; lane 4: normal control.

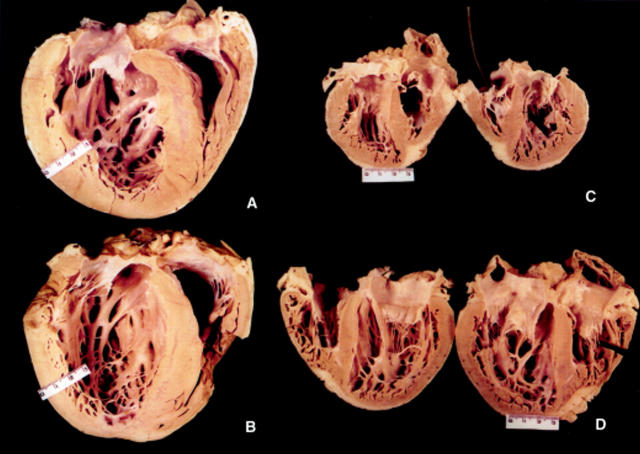

Figure 4 .

(A and B) Macroscopic views of the hearts excised at transplantation from the two probands of families A and B. Note the similar macroscopic pattern, intraseptal scarring, ventricular thickness, and dilatation. (C and D) Macroscopic views of the hearts excised at transplantation from the affected mother and son of family C. Septal hypertrophy is asymmetrical and more prominent in the mother's heart (II-2, C) than in the son's heart (III-1, D). Table 1 lists the height and body weight of patients.

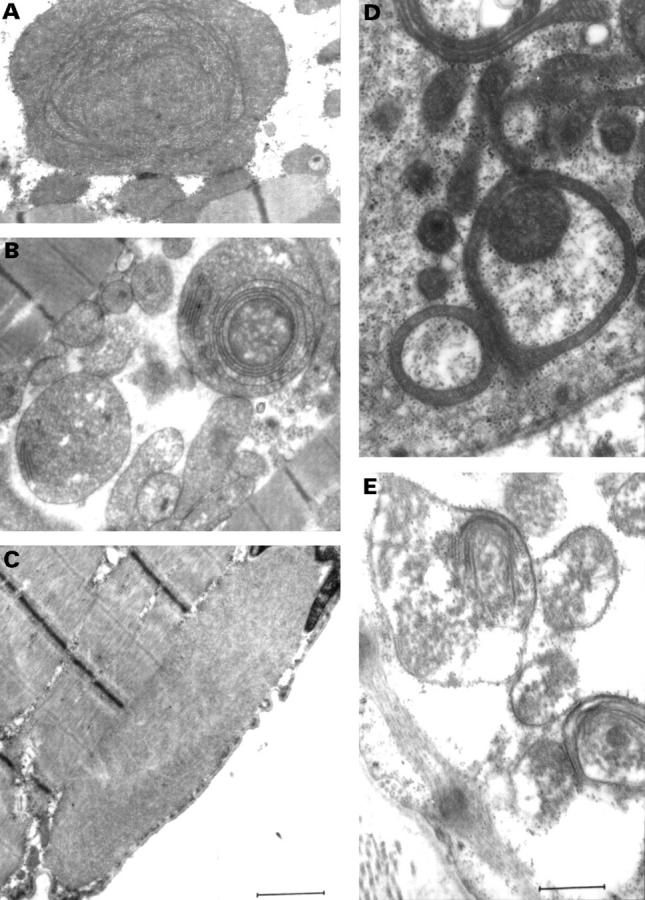

Figure 5 .

Electron micrographs of mitochondrial abnormalities. (A and B) Ring mitochondria, giant organelles with concentric cristae, and intramitochondrial inclusion bodies are seen in hearts of the two probands A IV-9 and B III-I (families A and B) (C) Hyaline bodies were seen in all skeletal muscle samples from the three families. (E) Mitochondria in the heart of the mother (family C) affected by hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Mitochondrial abnormalities in the heart of the mother and son of family C were identical. (Stain: uranyl acetate, lead citrate.) (Bar = 1.1 µm in A-C and 0.6 µm in D and E.)

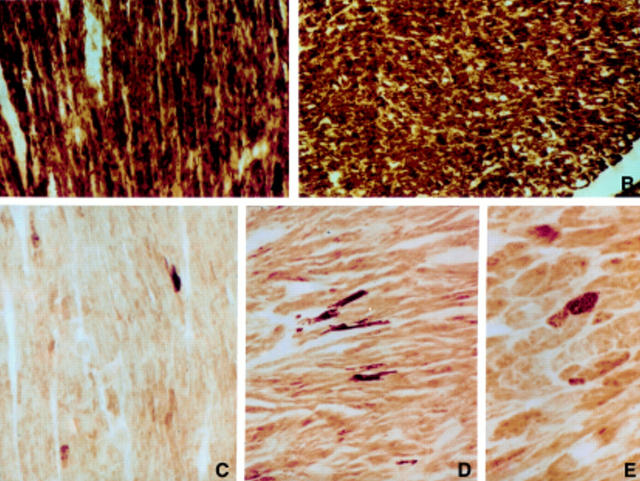

Figure 6 .

Light micrographs showing normal histochemical reactions for COX. (A) Donor heart biopsy specimen (original magnification ×160). (B) Heart of a patient with non-mitochondrial cardiomyopathy excised at transplantation (magnification ×120). (C-E) Histochemical reaction for COX in B-III-1, A-VI-1, and A-VI-9 compared with that in controls. The samples show a severe decrease in intensity of COX staining in most myocytes: very few fibres retain normal COX reaction (magnification C and D ×120, and E ×180).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anan R., Greve G., Thierfelder L., Watkins H., McKenna W. J., Solomon S., Vecchio C., Shono H., Nakao S., Tanaka H. Prognostic implications of novel beta cardiac myosin heavy chain gene mutations that cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1994 Jan;93(1):280–285. doi: 10.1172/JCI116957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S., Bankier A. T., Barrell B. G., de Bruijn M. H., Coulson A. R., Drouin J., Eperon I. C., Nierlich D. P., Roe B. A., Sanger F. Sequence and organization of the human mitochondrial genome. Nature. 1981 Apr 9;290(5806):457–465. doi: 10.1038/290457a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbustini E., Pucci A., Grasso M., Diegoli M., Pozzi R., Gavazzi A., Graziano G., Campana C., Goggi C., Martinelli L. Expression of natriuretic peptide in ventricular myocardium of failing human hearts and its correlation with the severity of clinical and hemodynamic impairment. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Oct 15;66(12):973–980. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90936-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bairoch A., Apweiler R. The SWISS-PROT protein sequence data bank and its new supplement TREMBL. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996 Jan 1;24(1):21–25. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black J. T., Judge D., Demers L., Gordon S. Ragged-red fibers. A biochemical and morphological study. J Neurol Sci. 1975 Dec;26(4):479–488. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(75)90048-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonne G., Carrier L., Bercovici J., Cruaud C., Richard P., Hainque B., Gautel M., Labeit S., James M., Beckmann J. Cardiac myosin binding protein-C gene splice acceptor site mutation is associated with familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Nat Genet. 1995 Dec;11(4):438–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1295-438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casali C., Santorelli F. M., D'Amati G., Bernucci P., DeBiase L., DiMauro S. A novel mtDNA point mutation in maternally inherited cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Aug 15;213(2):588–593. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coviello D. A., Maron B. J., Spirito P., Watkins H., Vosberg H. P., Thierfelder L., Schoen F. J., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Clinical features of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy caused by mutation of a "hot spot" in the alpha-tropomyosin gene. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Mar 1;29(3):635–640. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)00538-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A., Hammond H. A., Jin L., Caskey C. T., Chakraborty R. Genetic variation at five trimeric and tetrameric tandem repeat loci in four human population groups. Genomics. 1992 Feb;12(2):241–253. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(92)90371-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fananapazir L., Dalakas M. C., Cyran F., Cohn G., Epstein N. D. Missense mutations in the beta-myosin heavy-chain gene cause central core disease in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 May 1;90(9):3993–3997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaenicke T., Diederich K. W., Haas W., Schleich J., Lichter P., Pfordt M., Bach A., Vosberg H. P. The complete sequence of the human beta-myosin heavy chain gene and a comparative analysis of its product. Genomics. 1990 Oct;8(2):194–206. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(90)90272-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koga Y., Nonaka I., Sunohara N., Yamanaka R., Kumagai K. Variability in the activity of respiratory chain enzymes in mitochondrial myopathies. Acta Neuropathol. 1988;76(2):135–141. doi: 10.1007/BF00688097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfredi G., Schon E. A., Moraes C. T., Bonilla E., Berry G. T., Sladky J. T., DiMauro S. A new mutation associated with MELAS is located in a mitochondrial DNA polypeptide-coding gene. Neuromuscul Disord. 1995 Sep;5(5):391–398. doi: 10.1016/0960-8966(94)00079-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian A. J., Yu Q. T., Mares A., Jr, Hill R., Roberts R., Perryman M. B. Detection of a new mutation in the beta-myosin heavy chain gene in an individual with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1992 Dec;90(6):2156–2165. doi: 10.1172/JCI116101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maron B. J., Nichols P. F., 3rd, Pickle L. W., Wesley Y. E., Mulvihill J. J. Patterns of inheritance in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: assessment by M-mode and two-dimensional echocardiography. Am J Cardiol. 1984 Apr 1;53(8):1087–1094. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(84)90643-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merante F., Myint T., Tein I., Benson L., Robinson B. H. An additional mitochondrial tRNA(Ile) point mutation (A-to-G at nucleotide 4295) causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 1996;8(3):216–222. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(1996)8:3<216::AID-HUMU4>3.0.CO;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merante F., Tein I., Benson L., Robinson B. H. Maternally inherited hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to a novel T-to-C transition at nucleotide 9997 in the mitochondrial tRNA(glycine) gene. Am J Hum Genet. 1994 Sep;55(3):437–446. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolman J. C., Brink P. A., Corfield V. A. Identification of a new missense mutation at Arg403, a CpG mutation hotspot, in exon 13 of the beta-myosin heavy chain gene in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Hum Mol Genet. 1993 Oct;2(10):1731–1732. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.10.1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers R. M., Maniatis T., Lerman L. S. Detection and localization of single base changes by denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis. Methods Enzymol. 1987;155:501–527. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)55033-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obayashi T., Hattori K., Sugiyama S., Tanaka M., Tanaka T., Itoyama S., Deguchi H., Kawamura K., Koga Y., Toshima H. Point mutations in mitochondrial DNA in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am Heart J. 1992 Nov;124(5):1263–1269. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90410-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patella V., Marinò I., Lampärter B., Arbustini E., Adt M., Marone G. Human heart mast cells. Isolation, purification, ultrastructure, and immunologic characterization. J Immunol. 1995 Mar 15;154(6):2855–2865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poetter K., Jiang H., Hassanzadeh S., Master S. R., Chang A., Dalakas M. C., Rayment I., Sellers J. R., Fananapazir L., Epstein N. D. Mutations in either the essential or regulatory light chains of myosin are associated with a rare myopathy in human heart and skeletal muscle. Nat Genet. 1996 May;13(1):63–69. doi: 10.1038/ng0596-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayment I., Holden H. M., Sellers J. R., Fananapazir L., Epstein N. D. Structural interpretation of the mutations in the beta-cardiac myosin that have been implicated in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Apr 25;92(9):3864–3868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig A., Watkins H., Hwang D. S., Miri M., McKenna W., Traill T. A., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Preclinical diagnosis of familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy by genetic analysis of blood lymphocytes. N Engl J Med. 1991 Dec 19;325(25):1753–1760. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199112193252501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santorelli F. M., Mak S. C., El-Schahawi M., Casali C., Shanske S., Baram T. Z., Madrid R. E., DiMauro S. Maternally inherited cardiomyopathy and hearing loss associated with a novel mutation in the mitochondrial tRNA(Lys) gene (G8363A). Am J Hum Genet. 1996 May;58(5):933–939. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santorelli F. M., Mak S. C., Vàzquez-Acevedo M., González-Astiazarán A., Ridaura-Sanz C., González-Halphen D., DiMauro S. A novel mitochondrial DNA point mutation associated with mitochondrial encephalocardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995 Nov 22;216(3):835–840. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartore M., Grasso M., Piccolo G., Fasani R., Bergamaschi R., Malaspina A., Ceroni M., Kobayashi M., Semeraro A., Arbustini E. Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy (LHON)-related mitochondrial DNA sequence changes in italian patients presenting with sporadic bilateral optic neuritis. Biochem Mol Med. 1995 Oct;56(1):45–51. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1995.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestri G., Santorelli F. M., Shanske S., Whitley C. B., Schimmenti L. A., Smith S. A., DiMauro S. A new mtDNA mutation in the tRNA(Leu(UUR)) gene associated with maternally inherited cardiomyopathy. Hum Mutat. 1994;3(1):37–43. doi: 10.1002/humu.1380030107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sottocasa G. L., Kuylenstierna B., Ernster L., Bergstrand A. An electron-transport system associated with the outer membrane of liver mitochondria. A biochemical and morphological study. J Cell Biol. 1967 Feb;32(2):415–438. doi: 10.1083/jcb.32.2.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniike M., Fukushima H., Yanagihara I., Tsukamoto H., Tanaka J., Fujimura H., Nagai T., Sano T., Yamaoka K., Inui K. Mitochondrial tRNA(Ile) mutation in fatal cardiomyopathy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992 Jul 15;186(1):47–53. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(05)80773-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thierfelder L., Watkins H., MacRae C., Lamas R., McKenna W., Vosberg H. P., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Alpha-tropomyosin and cardiac troponin T mutations cause familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: a disease of the sarcomere. Cell. 1994 Jun 3;77(5):701–712. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikstrom K. L., Leinwand L. A. Contractile protein mutations and heart disease. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996 Feb;8(1):97–105. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H., McKenna W. J., Thierfelder L., Suk H. J., Anan R., O'Donoghue A., Spirito P., Matsumori A., Moravec C. S., Seidman J. G. Mutations in the genes for cardiac troponin T and alpha-tropomyosin in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1995 Apr 20;332(16):1058–1064. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199504203321603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H., Rosenzweig A., Hwang D. S., Levi T., McKenna W., Seidman C. E., Seidman J. G. Characteristics and prognostic implications of myosin missense mutations in familial hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. N Engl J Med. 1992 Apr 23;326(17):1108–1114. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199204233261703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H., Thierfelder L., Anan R., Jarcho J., Matsumori A., McKenna W., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Independent origin of identical beta cardiac myosin heavy-chain mutations in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Hum Genet. 1993 Dec;53(6):1180–1185. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watkins H., Thierfelder L., Hwang D. S., McKenna W., Seidman J. G., Seidman C. E. Sporadic hypertrophic cardiomyopathy due to de novo myosin mutations. J Clin Invest. 1992 Nov;90(5):1666–1671. doi: 10.1172/JCI116038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeviani M., Gellera C., Antozzi C., Rimoldi M., Morandi L., Villani F., Tiranti V., DiDonato S. Maternally inherited myopathy and cardiomyopathy: association with mutation in mitochondrial DNA tRNA(Leu)(UUR). Lancet. 1991 Jul 20;338(8760):143–147. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)90136-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]