Abstract

Objective—To examine the validity of estimates of coronary heart disease (CHD) risk by the Framingham risk function, for European populations. Design—Comparison of CHD risk estimates for individuals derived from the Framingham, prospective cardiovascular Münster (PROCAM), Dundee, and British regional heart (BRHS) risk functions. Setting—Sheffield Hypertension Clinic. Patients—206 consecutive hypertensive men aged 35-75 years without preexisting vascular disease. Results—There was close agreement among the Framingham, PROCAM, and Dundee risk functions for average CHD risk. For individuals the best correlation was between Framingham and PROCAM, both of which use high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. When Framingham was used to target a CHD event rate > 3% per year, it identified men with mean CHD risk by PROCAM of 4.6% per year and all had CHD event risks > 1.5% per year. Men at lower risk by Framingham had a mean CHD risk by PROCAM of 1.5% per year, with 16% having a CHD event risk > 3.0% per year. BRHS risk function estimates of CHD risk were fourfold lower than those for the other three risk functions, but with moderate correlations, suggesting an important systematic error. Conclusion—There is close agreement between the Framingham, PROCAM, and Dundee risk functions as regards average CHD risk, and moderate agreement for estimates within individuals. Taking PROCAM as the external standard, the Framingham function separates high and low CHD risk groups and is acceptably accurate for northern European populations, at least in men. Keywords: ischaemic heart disease; prevention; risk factors

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (163.0 KB).

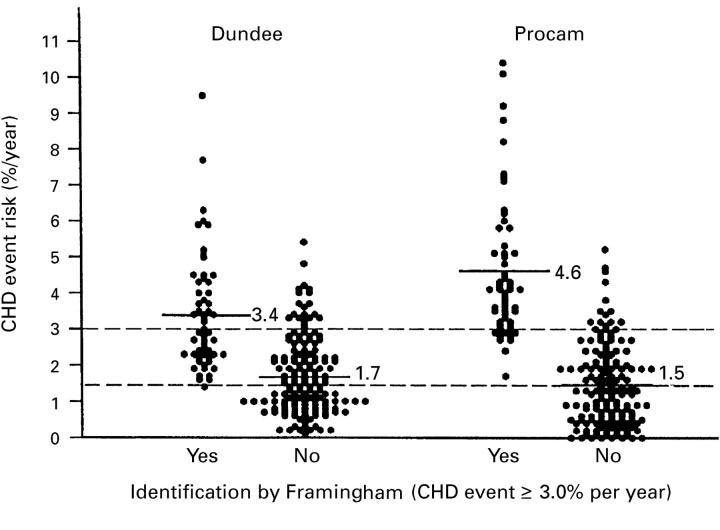

Figure 1 .

Individual risk estimates by the Framingham function v the PROCAM function. (A) Dashed line = line of identity; solid line = regression line. (B) Bland-Altman plot.

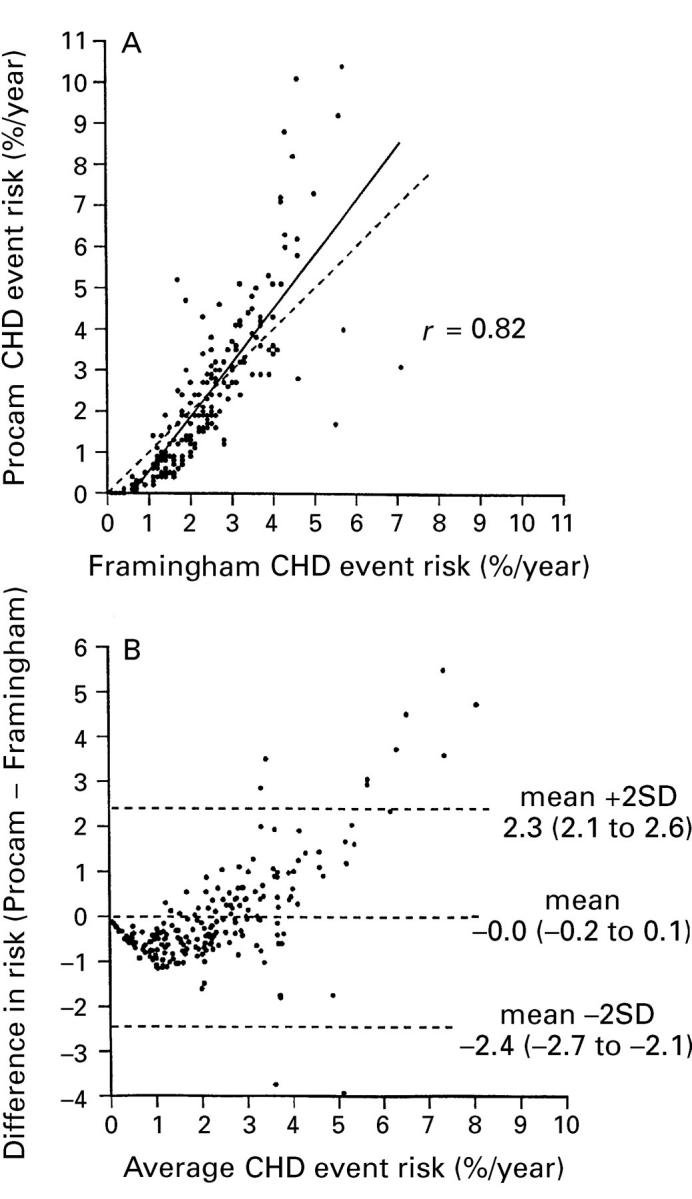

Figure 2 .

Individual risk estimates by the Framingham function v the Dundee function. (A) Dashed line = line of identity; solid line = regression line. (B) Bland-Altman plot.

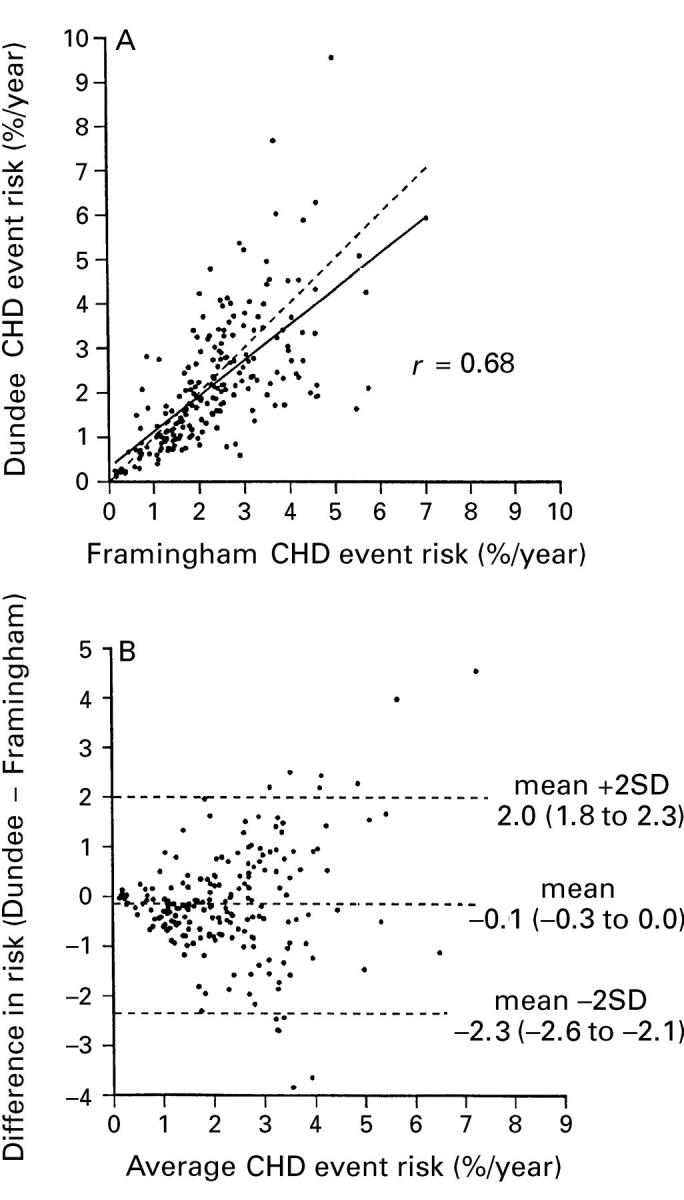

Figure 3 .

Individual risk estimates by the Framingham function v the BHRS function. (A) Dashed line = line of identity; solid line = regression line. (B) Bland-Altman plot.

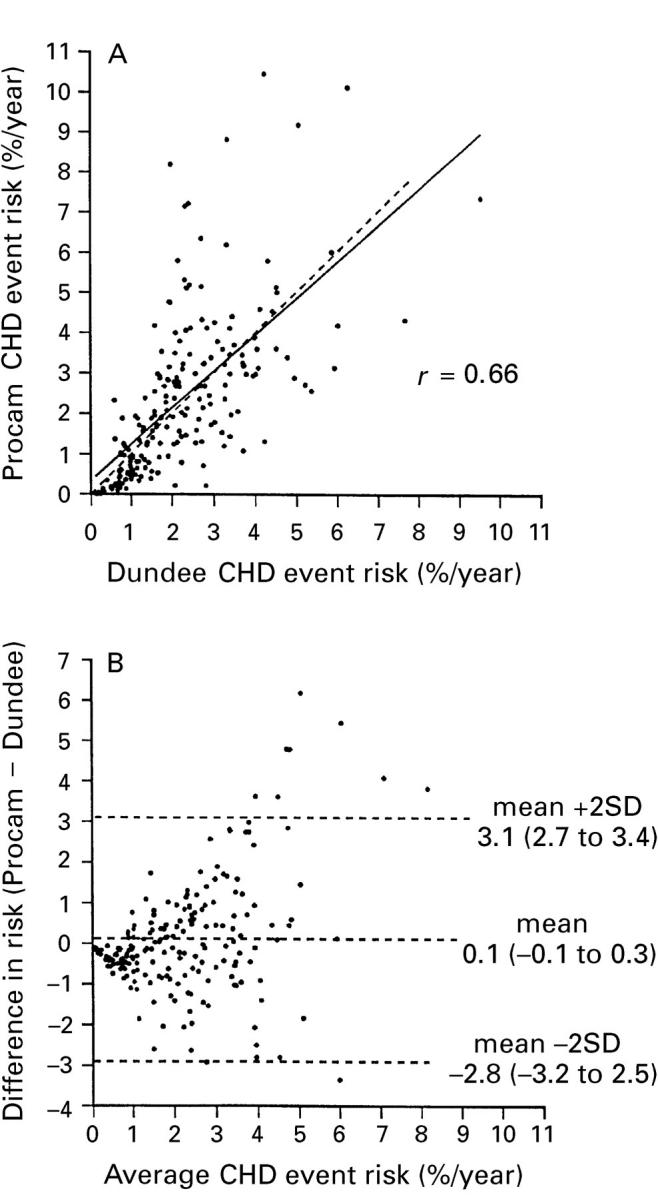

Figure 4 .

Individual risk estimates by the Dundee function v the PROCAM function. (A) Dashed line = line of identity; solid line = regression line. (B) Bland-Altman plot.

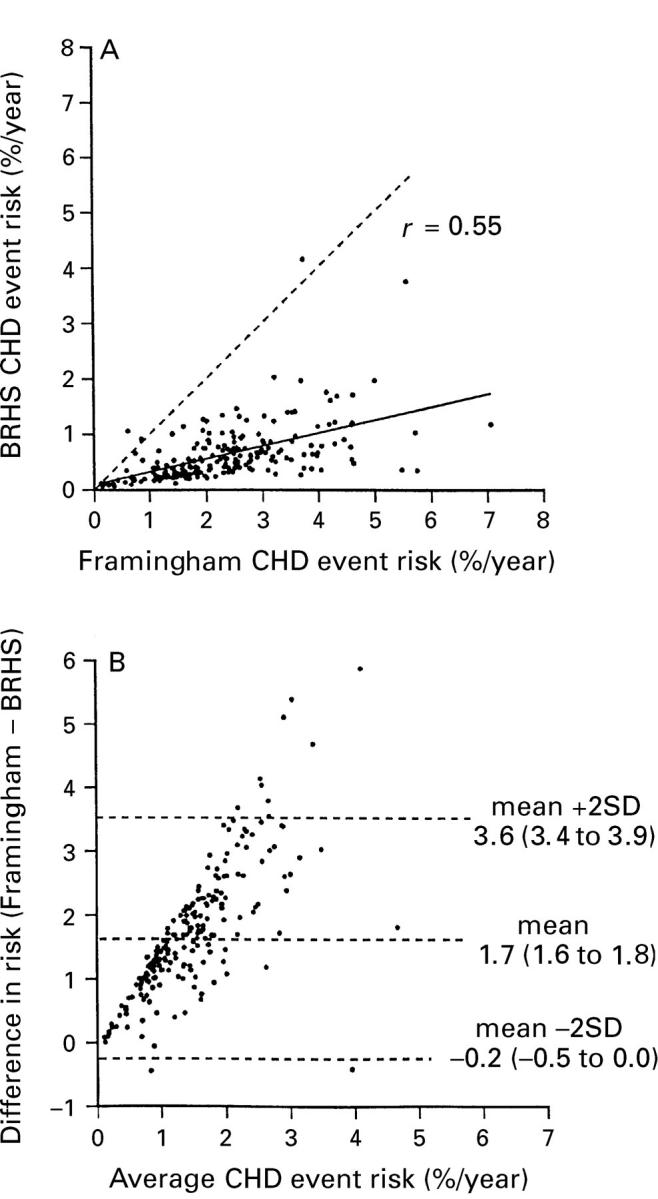

Figure 5 .

Distribution of risk estimates by the Dundee and PROCAM risk functions in individuals identified as having coronary risks above or below 3% per year by the Framingham risk function. Numbers are the mean risks estimated by the Dundee or PROCAM functions in each group.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Anderson K. M., Odell P. M., Wilson P. W., Kannel W. B. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991 Jan;121(1 Pt 2):293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland J. M., Altman D. G. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986 Feb 8;1(8476):307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand R. J., Rosenman R. H., Sholtz R. I., Friedman M. Multivariate prediction of coronary heart disease in the Western Collaborative Group Study compared to the findings of the Framingham study. Circulation. 1976 Feb;53(2):348–355. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.53.2.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambless L. E., Dobson A. J., Patterson C. C., Raines B. On the use of a logistic risk score in predicting risk of coronary heart disease. Stat Med. 1990 Apr;9(4):385–396. doi: 10.1002/sim.4780090410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook R. J., Sackett D. L. The number needed to treat: a clinically useful measure of treatment effect. BMJ. 1995 Feb 18;310(6977):452–454. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6977.452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon T., Garcia-Palmieri M. R., Kagan A., Kannel W. B., Schiffman J. Differences in coronary heart disease in Framingham, Honolulu and Puerto Rico. J Chronic Dis. 1974 Sep;27(7-8):329–344. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(74)90013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. A., Coupal L., Hu X. P. Identifying adults at increased risk of coronary disease. How well do the current cholesterol guidelines work? JAMA. 1995 Sep 13;274(10):801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. A., Lowensteyn I., Esrey K. L., Steinert Y., Joseph L., Abrahamowicz M. Do doctors accurately assess coronary risk in their patients? Preliminary results of the coronary health assessment study. BMJ. 1995 Apr 15;310(6985):975–978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6985.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq I. U., Jackson P. R., Yeo W. W., Ramsay L. E. Sheffield risk and treatment table for cholesterol lowering for primary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1995 Dec 2;346(8988):1467–1471. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92477-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson R., Barham P., Bills J., Birch T., McLennan L., MacMahon S., Maling T. Management of raised blood pressure in New Zealand: a discussion document. BMJ. 1993 Jul 10;307(6896):107–110. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6896.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrett R. J., Shipley M. J., Rose G. Weight and mortality in the Whitehall Study. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1982 Aug 21;285(6341):535–537. doi: 10.1136/bmj.285.6341.535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johannesson M. The cost effectiveness of hypertension treatment in Sweden. Pharmacoeconomics. 1995 Mar;7(3):242–250. doi: 10.2165/00019053-199507030-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A., Aravanis C., Blackburn H., Van Buchem F. S., Buzina R., Djordjevic B. S., Fidanza F., Karvonen M. J., Menotti A., Puddu V. Probability of middle-aged men developing coronary heart disease in five years. Circulation. 1972 Apr;45(4):815–828. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.45.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keys A., Menotti A., Aravanis C., Blackburn H., Djordevic B. S., Buzina R., Dontas A. S., Fidanza F., Karvonen M. J., Kimura N. The seven countries study: 2,289 deaths in 15 years. Prev Med. 1984 Mar;13(2):141–154. doi: 10.1016/0091-7435(84)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurier D., Nguyen P. C., Cazelles B., Segond P. Estimation of CHD risk in a French working population using a modified Framingham model. The PCV-METRA Group. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Dec;47(12):1353–1364. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leaverton P. E., Sorlie P. D., Kleinman J. C., Dannenberg A. L., Ingster-Moore L., Kannel W. B., Cornoni-Huntley J. C. Representativeness of the Framingham risk model for coronary heart disease mortality: a comparison with a national cohort study. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(8):775–784. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90129-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyörälä K., De Backer G., Graham I., Poole-Wilson P., Wood D. Prevention of coronary heart disease in clinical practice. Recommendations of the Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology, European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Hypertension. Eur Heart J. 1994 Oct;15(10):1300–1331. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay L. E., Haq I. U., Jackson P. R., Yeo W. W., Pickin D. M., Payne J. N. Targeting lipid-lowering drug therapy for primary prevention of coronary disease: an updated Sheffield table. Lancet. 1996 Aug 10;348(9024):387–388. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)05516-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay L. E., Haq I. U., Jackson P. R., Yeo W. W. The Sheffield table for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: corrected. Lancet. 1996 Nov 2;348(9036):1251–1251. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)65536-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay L. E., ul Haq I., Yeo W. W., Jackson P. R. Interpretation of prospective trials in hypertension: do treatment guidelines accurately reflect current evidence? J Hypertens Suppl. 1996 Dec;14(5):S187–S194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson J. Information needed to decide about cardiovascular treatment in primary care. BMJ. 1997 Jan 25;314(7076):277–280. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7076.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., Tunstall-Pedoe H. D., Heller R. F. UK heart disease prevention project: incidence and mortality results. Lancet. 1983 May 14;1(8333):1062–1066. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)91907-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Phillips A. N., Walker M. Identifying men at high risk of heart attacks: strategy for use in general practice. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986 Aug 23;293(6545):474–479. doi: 10.1136/bmj.293.6545.474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd J., Cobbe S. M., Ford I., Isles C. G., Lorimer A. R., MacFarlane P. W., McKillop J. H., Packard C. J. Prevention of coronary heart disease with pravastatin in men with hypercholesterolemia. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995 Nov 16;333(20):1301–1307. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199511163332001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson S. G., Pyke S. D., Wood D. A. Using a coronary risk score for screening and intervention in general practice. British Family Heart Study. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1996 Jun;3(3):301–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ul Haq I., Ramsay L. E., Pickin D. M., Yeo W. W., Jackson P. R., Payne J. N. Lipid-lowering for prevention of coronary heart disease: what policy now? Clin Sci (Lond) 1996 Oct;91(4):399–413. doi: 10.1042/cs0910399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]