Abstract

Objective—To compare the atrial and ventricular myoarchitecture in the normal heart and the heart with tricuspid atresia, and to investigate changes in the three dimensional arrangement of collagen fibrils. Methods—Blunt dissection and cell maceration with scanning electron microscopy were used to study the architecture of the atrial and ventricular musculature and the arrangement of collagen fibrils in three specimens with tricuspid atresia and six normal human hearts. Results—There were significant modifications in the myoarchitecture of the right atrium and the left ventricle, both being noticeably hypertrophied. The middle layer of the ventricle in the abnormal hearts was thicker than in the normal hearts. The orientation of the superficial layer in the left ventricle in hearts with tricuspid atresia was irregular compared with the normal hearts. Scanning electron microscopy showed coarser endomysial sheaths and denser perimysial septa in hearts with tricuspid atresia than in normal hearts. Conclusions—The overall architecture of the muscle fibres and its connective tissue matrix in hearts with tricuspid atresia differed from normal, probably reflecting modelling of the myocardium that is inherent to the malformation. This is in concordance with clinical observations showing deterioration in pump function of the dominant left ventricle from very early in life. Keywords: tricuspid atresia; congenital heart defects; connective tissue; fibrosis

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (388.6 KB).

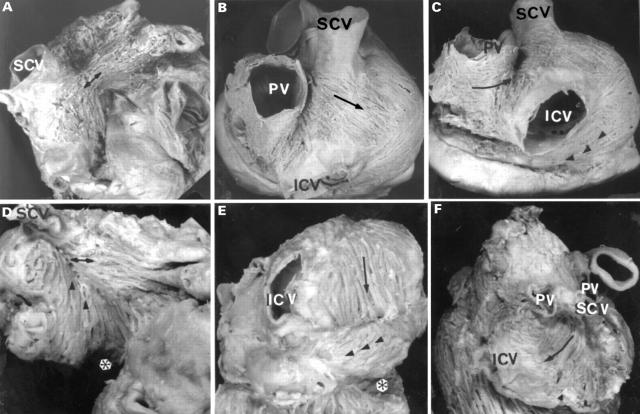

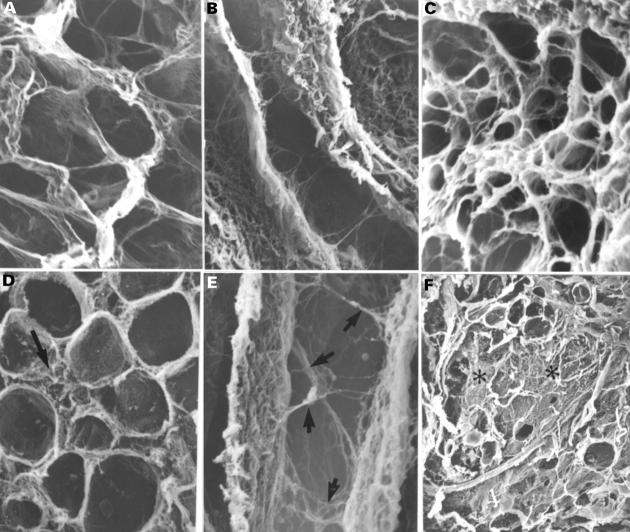

Figure 1 .

External views of the normal atria (A, B, C) and tricuspid atresia specimens (D, E, F), showing the arrangement of the subepicardial fibres on anterior (A, D) and posterior sectors (B, C, E, F). Note in panel A, Bachmann's bundle (double arrows) coursing horizontally from the cavoatrial junction to the left appendage. In contrast, in panel D the fibres of Bachmann's bundle tend to be aligned obliquely meeting with the fibres from the floor of the right atrium (arrowheads). In the posterior sector note (panel B) an intercaval bundle with a component of fibres obliquely from left to right (arrow) across the terminal groove, and an another component running obliquely from right to left (arrowheads in panel C) covered the dorsal wall of the coronary sinus. On the left atrium the fibres run circumferentially (arrow) into the posterior interatrial groove (panel C) and pass anteriorly to join the interatrial band. In contrast, in the specimens with tricuspid atresia, the intercaval bundle shows a preferentially longitudinal direction between the caval veins (arrow, panels E and F) and a horizontal component in the floor of the right atrium (arrowheads, panel E). In the left atrium the fibres were arranged irregularly without one clear direction. A, aorta; ICV, inferior caval vein; LA, left appendage; PV, right pulmonary veins; RA, right appendage; SVC, superior caval vein. *Absence of right atrioventricular connection.

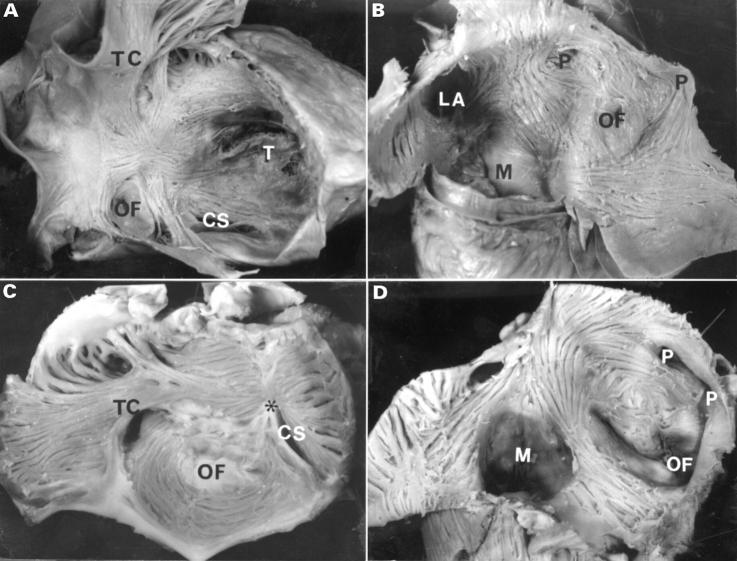

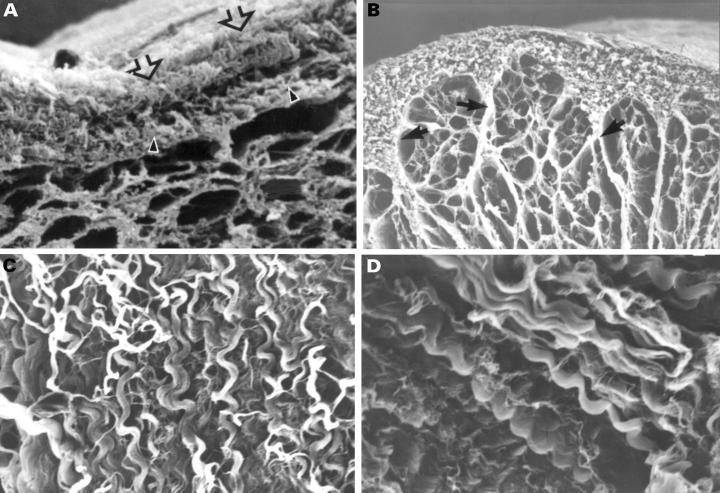

Figure 2 .

Internal view of the right atrium (A, C) and left atrium (B, D) after removal of the endocardium. Note in the normal right atrium (panel A) the arrangement of the fibres is distinctly different from that in the tricuspid atresia specimen (panel C). On the inner surface of the normal left atrium (panel B) fibres encircle the oval fossa, pulmonary veins, and the atrial appendage. Note in tricuspid atresia (panel D) there is a prominent circular pattern around the oval fossa and fewer longitudinal fibres toward the mitral valve. CS, orifice of the coronary sinus; LA, orifice of the left appendage; M, mitral valve; OF, oval fossa; P, orifices of pulmonary veins; T, tricuspid valve; TC, terminal crest. *Dimple.

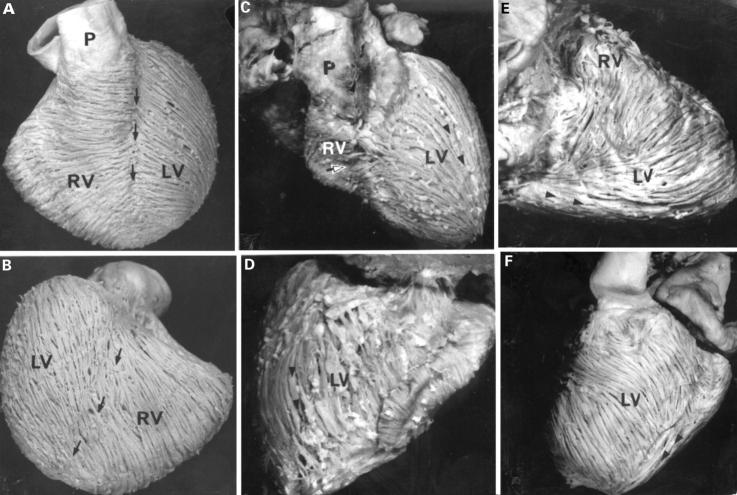

Figure 3 .

Views of the hearts of normal (A, B) and tricuspid atresia specimens (C, D, E, F), showing the arrangement of the ventricular fibres of the superficial layer. In panels A and B the fibres run obliquely across the interventricular grooves (arrows), although the posterior interventricular groove is less evident. The corresponding sternocostal surface (panel C) and diaphragmatic surface (panel D) of the heart with tricuspid atresia from a patient aged 8 years show lack of interventricular grooves. Note the longitudinal fibres (arrowheads) in the left ventricle. Panels E and F show right and left margins respectively of a heart from a one month old patient. The right ventricle is hypoplastic whereas the left ventricle is profoundly hypertrophied in this case. Note the longitudinal fibres (arrowheads) on the diaphragmatic surface. A, aorta; LV, left ventricle; P, pulmonary trunk; RV, right ventricle. Open arrow, horizontal fibres; arrowheads, longitudinal fibres.

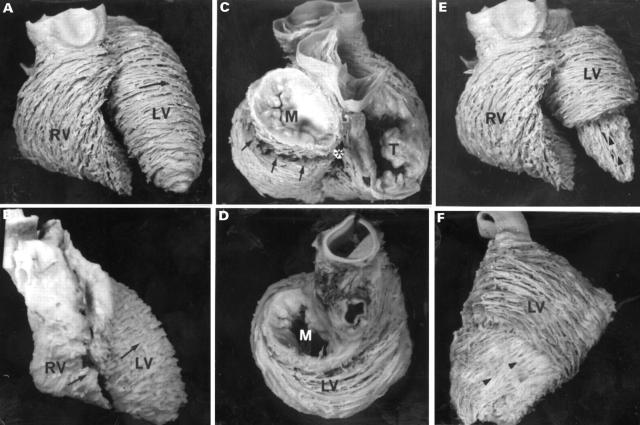

Figure 4 .

Views of the normal heart (A, C, E) and tricuspid atresia specimens (B, D, F), showing the arrangement of the ventricular fibres in the middle (A-D) and deep layers (E, F). The sternocostal aspects (panels A and E) show the circular arrangement (arrow) of the left ventricular fibres, in contrast to the oblique arrangement of the right ventricular fibres in the normal heart. A comparable view of the abnormal heart (panel B) shows circular fibres in both ventricles (arrows). The basal views (panels C and D) show the distinct invagination at the crux (asterix) and the basal aperture (arrows) in the normal heart, whereas the left ventricle predominates in the abnormal heart where there is no evidence whatever of the tricuspid valve (panel D). The deep layers (arrowheads) are revealed by removing the apical half of the middle layer (panels E and F). The heart with tricuspid atresia is rotated to show its left (obtuse) margin. A, aorta; LV, left ventricle; M, mitral valve; P, pulmonary trunk; RV, right ventricle; T, tricuspid valve.

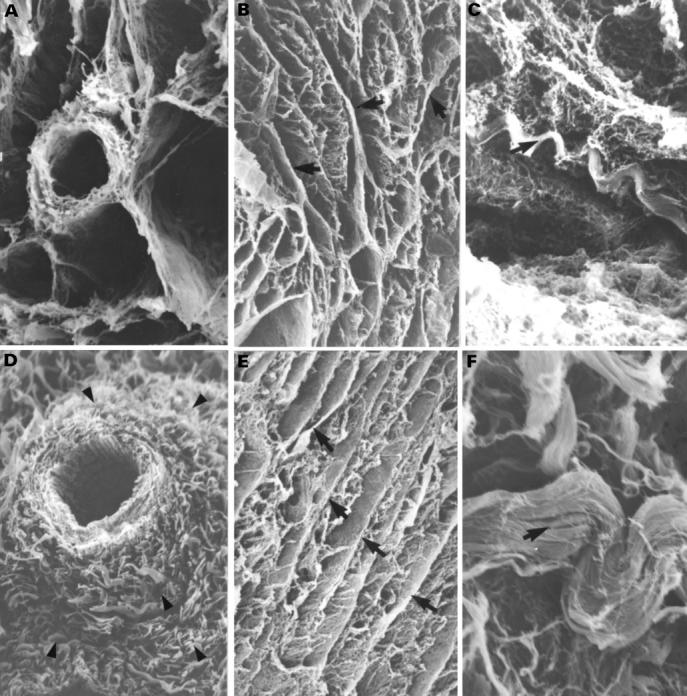

Figure 5 .

Scanning electron micrographs show the spatial arrangement of the endomysial component after NaOH digestion of the myocardial cells in the left ventricle of the normal heart (A, B, C) and tricuspid atresia specimen (D, E, F). Note in panel D the disrupted endomysial sheath (arrow), in panel E the network of struts (arrows), and in panel F the areas of interstitial fibrosis (asterisks). Magnifications: panels A and D, ×392; panels B and E, ×522; panels C and F, ×94. Normal: 1 month; tricuspid atresia: 2 months.

Figure 6 .

Scanning electron micrographs showing the spatial arrangement of the perimysial component around the blood vessel in a normal heart (A) and with perivascular fibrosis (arrowheads) in tricuspid atresia specimen (D). Structurally the perimysial component in the normal heart (B, C) and tricuspid atresia specimen (E, F) is composed of septa that separate muscle bundles (B, E) and spiral tracts (coiled perimysial fibres) (arrows) that run obliquely or parallel to the septa (C, F). The heart with tricuspid atresia show more numerous perimysial septa (arrows, panel E) and coarser spiral tracts (arrow, panel F). Magnifications: panels A and D, ×261; panels B and E, ×52; panel C, ×313; panel F, ×522. Normal: 4 months; tricuspid atresia: 4 months.

Figure 7 .

Scanning electron micrographs showing the epimysial component in normal (A, B, C) and tricuspid atresia specimens (D). The outer layer of the epimysium (panel A) has many spiral fibres (panel C) between epicardium (open arrow) and the inner layer of epimysium (arrowhead). The inner layer is continuous with perimysial septa (arrows, panel B). In tricuspid atresia specimens the spiral tracts were coarser than in normal hearts (panel D). Magnifications: panel A, ×73; panel B, ×52; panels C and D, ×311. Normal, panel A: 5 years; panels B and C: 1 month; tricuspid atresia: 2 years.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Baker E. J., Jones O. D., Joseph M. C., Maisey M. N., Tynan M. J. Radionuclide measurement of left ventricular ejection fraction in tricuspid atresia. Br Heart J. 1984 Nov;52(5):572–574. doi: 10.1136/hrt.52.5.572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carew T. E., Covell J. W. Fiber orientation in hypertrophied canine left ventricle. Am J Physiol. 1979 Mar;236(3):H487–H493. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield J. B., Borg T. K. The collagen network of the heart. Lab Invest. 1979 Mar;40(3):364–372. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caulfield J. B., Janicki J. S. Structure and function of myocardial fibrillar collagen. Technol Health Care. 1997 Apr;5(1-2):95–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contard F., Koteliansky V., Marotte F., Dubus I., Rappaport L., Samuel J. L. Specific alterations in the distribution of extracellular matrix components within rat myocardium during the development of pressure overload. Lab Invest. 1991 Jan;64(1):65–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Teran M. A., Hurle J. M. Myocardial fiber architecture of the human heart ventricles. Anat Rec. 1982 Oct;204(2):137–147. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092040207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRANT R. P. NOTES ON THE MUSCULAR ARCHITECTURE OF THE LEFT VENTRICLE. Circulation. 1965 Aug;32:301–308. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.32.2.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson D. G., Traill T. A., Brown D. J. Abnormal ventricular function in patients with univentricular heart. Cineangiographic study. Herz. 1979 Apr;4(2):226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenbaum R. A., Ho S. Y., Gibson D. G., Becker A. E., Anderson R. H. Left ventricular fibre architecture in man. Br Heart J. 1981 Mar;45(3):248–263. doi: 10.1136/hrt.45.3.248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho S. Y., Jackson M., Kilpatrick L., Smith A., Gerlis L. M. Fibrous matrix of ventricular myocardium in tricuspid atresia compared with normal heart. A quantitative analysis. Circulation. 1996 Oct 1;94(7):1642–1646. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.7.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones C. J., Song G. J., Gibson D. G. An echocardiographic assessment of atrial mechanical behaviour. Br Heart J. 1991 Jan;65(1):31–36. doi: 10.1136/hrt.65.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jouk P. S., Usson Y., Michalowicz G., Parazza F. Mapping of the orientation of myocardial cells by means of polarized light and confocal scanning laser microscopy. Microsc Res Tech. 1995 Apr 15;30(6):480–490. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070300605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund D. D., Twietmeyer T. A., Schmid P. G., Tomanek R. J. Independent changes in cardiac muscle fibres and connective tissue in rats with spontaneous hypertension, aortic constriction and hypoxia. Cardiovasc Res. 1979 Jan;13(1):39–44. doi: 10.1093/cvr/13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean M. R., Prothero J. Coordinated three-dimensional reconstruction from serial sections at macroscopic and microscopic levels of resolution: the human heart. Anat Rec. 1987 Dec;219(4):374-7, 434-9. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092190415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtani O., Ushiki T., Taguchi T., Kikuta A. Collagen fibrillar networks as skeletal frameworks: a demonstration by cell-maceration/scanning electron microscope method. Arch Histol Cytol. 1988 Jul;51(3):249–261. doi: 10.1679/aohc.51.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orie J. D., Anderson C., Ettedgui J. A., Zuberbuhler J. R., Anderson R. H. Echocardiographic-morphologic correlations in tricuspid atresia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Sep;26(3):750–758. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00250-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman E. S., Weber K. T., Janicki J. S., Pietra G. G., Fishman A. P. Muscle fiber orientation and connective tissue content in the hypertrophied human heart. Lab Invest. 1982 Feb;46(2):158–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redington A. N., Knight B., Oldershaw P. J., Shinebourne E. A., Rigby M. L. Left ventricular function in double inlet left ventricle before the Fontan operation: comparison with tricuspid atresia. Br Heart J. 1988 Oct;60(4):324–331. doi: 10.1136/hrt.60.4.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Quintana D., Anderson R. H., Ho S. Y. Ventricular myoarchitecture in tetralogy of Fallot. Heart. 1996 Sep;76(3):280–286. doi: 10.1136/hrt.76.3.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Quintana D., Garcia-Martinez V., Climent V., Hurle J. M. Morphological changes in the normal pattern of ventricular myoarchitecture in the developing human heart. Anat Rec. 1995 Dec;243(4):483–495. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092430411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach M. S., Dolber P. C., Heidlage J. F. Influence of the passive anisotropic properties on directional differences in propagation following modification of the sodium conductance in human atrial muscle. A model of reentry based on anisotropic discontinuous propagation. Circ Res. 1988 Apr;62(4):811–832. doi: 10.1161/01.res.62.4.811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spach M. S., Dolber P. C. Relating extracellular potentials and their derivatives to anisotropic propagation at a microscopic level in human cardiac muscle. Evidence for electrical uncoupling of side-to-side fiber connections with increasing age. Circ Res. 1986 Mar;58(3):356–371. doi: 10.1161/01.res.58.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoele D. G., Ursell P. C., Ho S. Y., Smith A., Bowman F. O., Gersony W. M., Anderson R. H. Atrial morphologic features in tricuspid atresia. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991 Oct;102(4):606–610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrent Guasp F. La estructuración macroscópica del miocardio ventricular. Rev Esp Cardiol. 1980;33(3):265–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K., Ho S. Y., Gibson D. G., Anderson R. H. Architecture of atrial musculature in humans. Br Heart J. 1995 Jun;73(6):559–565. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.6.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K. T., Brilla C. G. Pathological hypertrophy and cardiac interstitium. Fibrosis and renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system. Circulation. 1991 Jun;83(6):1849–1865. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.83.6.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber K. T., Janicki J. S. The heart as a muscle--pump system and the concept of heart failure. Am Heart J. 1979 Sep;98(3):371–384. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(79)90051-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]