Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (135.7 KB).

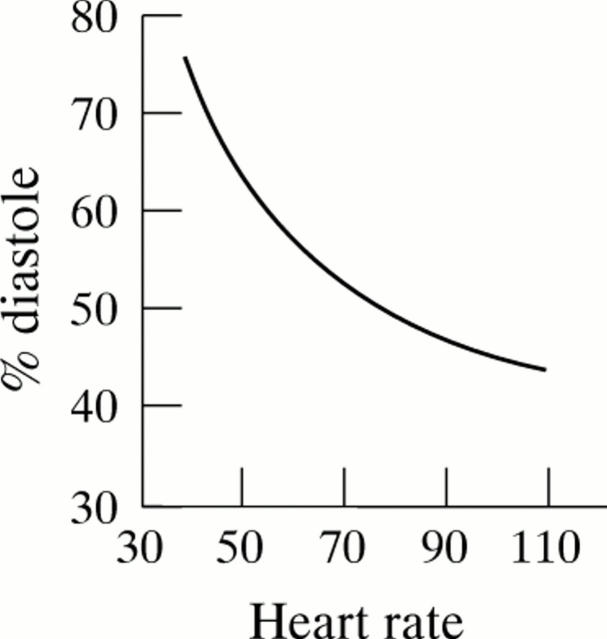

Figure 1 .

Relation between heart rate and percentage diastole. Because of the non-linearity of the relation, a small decrease in heart rate results, at lower heart rates especially, in a dramatic increase in the diastolic part of the cardiac cycle. (Reproduced from Boudoulas H, Rittgers SE, Lewis RP, et al. Circulation 1979;60:164-9, with permission of American Heart Association.)

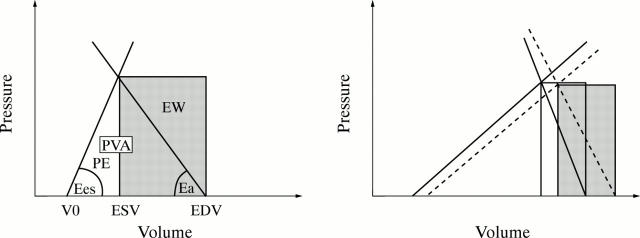

Figure 2 .

(Left) Work efficiency in normal subjects. Ees represents the slope of the left ventricular end systolic pressure−volume relation, and Ea the slope of the arterial end systolic pressure−stroke volume relation. External work (EW) (area in grey), the mechanical cardiac work, represents the area bounded by the pressure−volume trajectory of one beat. Pressure−volume area (PVA) represents the area bounded by the end systolic pressure−volume relation, the end diastolic pressure−volume relation, and the systolic pressure−volume trajectory of the contraction. Potential energy (PE) is the difference between PVA and EW. EW/PVA represents the work efficiency. ESV, end systolic volume; EDV, end diastolic volume; V0 is the volume axis intercept of the end systolic pressure−volume relation. (Right) Effect of a heart rate lowering drug on work efficiency in patients with heart failure. In comparison with basal conditions (solid lines and white area), negative chronotropic effect (dashed lines and grey area) considerably reduces Ea and Ees to a lower extent, resulting in a fall in the Ea/Ees ratio, so that EW/PVA significantly increases, meaning an increase in work efficiency. (Adapted from Yamakawa H, Takeuchi M, Takaoka H, et al. Circulation 1996;94:340-5, with permission of American Heart Association.)

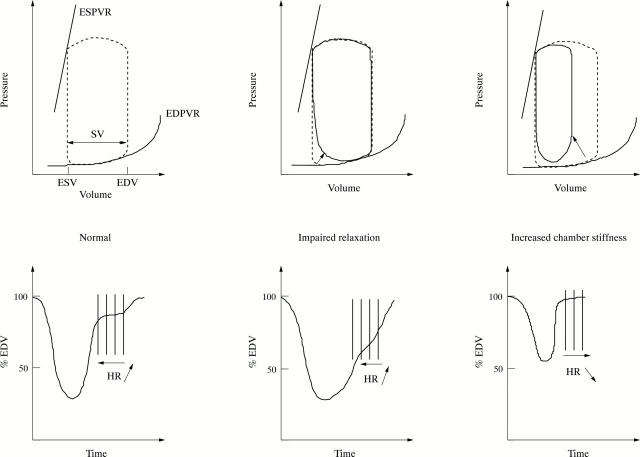

Figure 3 .

Force−frequency relation in human hearts. The figure displays the force−frequency relation developed by papillary muscles of six normal subjects and six patients with heart failure (cardiomyopathy) in response to a progressive increase in stimulation frequency. Force increases with the increase in stimulation frequency in normal subjects (open symbols), up to a critical frequency above which it decreases. In heart failure (filled symbols), the force−frequency slope is considerably decreased. Increasing the stimulation frequency does not produce a meaningful increase of force; furthermore, the point of inflexion occurs at a low frequency. This explains why, at high heart rates, the force of contraction of cardiac fibres of patients with heart failure is not increased, and may even be decreased. Negative chronotropic agents shift the operating frequencies during exercise to the left part of the axis, which may in part explain their beneficial effect on cardiac function. (Reproduced from Mulieri LA, Hasenfuss G, Leavitt B, et al. Circulation 1992;85:1743-50, with permission of American Heart Association.)

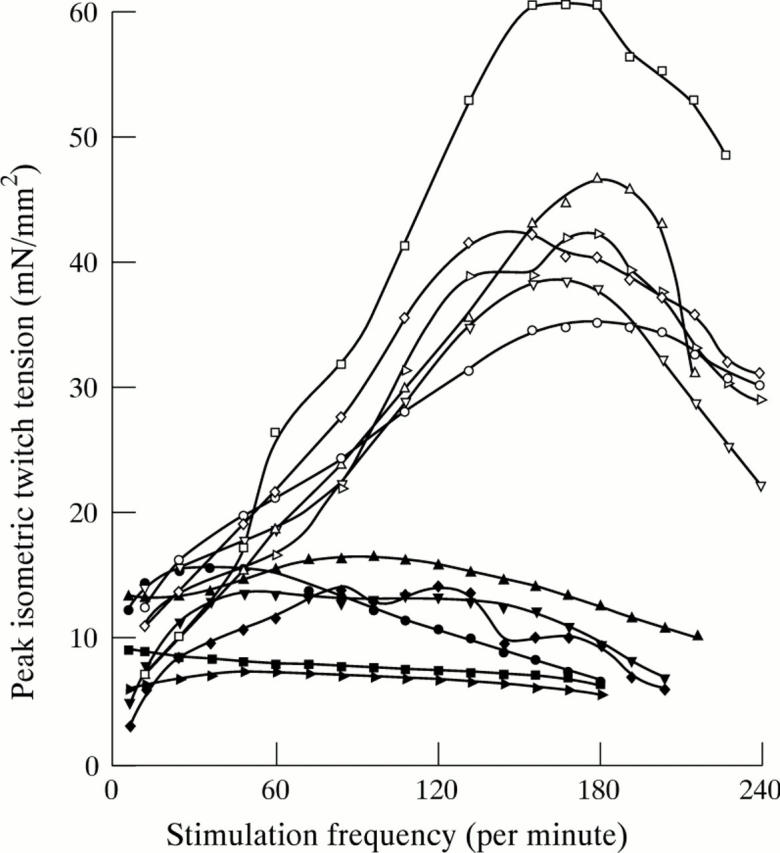

Figure 4 .

Effects of heart rate increase on left ventricular filling (the same model applies for the three parts of the figure). Top of figure: pressure−volume relation (ESV, end systolic volume; ESPVR, end systolic pressure−volume relation; EDV, end diastolic volume; EDVPR, end diastolic pressure−volume relation; SV, stroke volume). Bottom of figure: left ventricular volume changes (expressed in percentage end diastolic volume (EDV)) during one cardiac cycle. Vertical lines summarise the consequences of heart rate (HR) variations on left ventricular filling volume. Depending on the context, various increases in heart rate (leftward displacement of arrow) result in modifications of left ventricular volume filling. In normal subjects (left part of the figure) with normal pressure−volume relation (dashed line loop), modifications of heart rate mainly affect diastasis. Volume changes during this period are minor, with most of the filling occurring in early and late diastole, so that tachycardia, up to a critical limit, does not significantly affect ventricular volume. In patients with impaired relaxation (middle part of the figure), because of the delayed early diastolic rapid filling phase (solid line loop in the top of the figure), diastasis is shortened or abolished and atrial systolic filling is increased in compensation for the reduced contribution of rapid filling. So, inappropriate tachycardia will significantly reduce ventricular filling. This explains the benefit of heart rate lowering drugs in patients with impaired relaxation and heart failure caused by inappropriate tachycardia. Finally, in patients with increased chamber stiffness (right part of the figure), stroke volume is reduced (solid line loop in the top of the figure) and there is a leftward and upward displacement of the end diastolic pressure−volume relation (arrow). So, tachycardia represents a compensatory response to reduced systolic ejection volume. In these patients, a heart rate lowering drug may have a deleterious effect, by creating an important increase of pressure levels even with small volume variations, caused by the steep end diastolic pressure−volume relation.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aroesty J. M., McKay R. G., Heller G. V., Royal H. D., Als A. V., Grossman W. Simultaneous assessment of left ventricular systolic and diastolic dysfunction during pacing-induced ischemia. Circulation. 1985 May;71(5):889–900. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.71.5.889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asanoi H., Sasayama S., Kameyama T. Ventriculoarterial coupling in normal and failing heart in humans. Circ Res. 1989 Aug;65(2):483–493. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.2.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere P. A., Glagov S., Zarins C. K. Experimental atherosclerosis at the carotid bifurcation of the cynomolgus monkey. Localization, compensatory enlargement, and the sparing effect of lowered heart rate. Arterioscler Thromb. 1992 Nov;12(11):1245–1253. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.12.11.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beere P. A., Glagov S., Zarins C. K. Retarding effect of lowered heart rate on coronary atherosclerosis. Science. 1984 Oct 12;226(4671):180–182. doi: 10.1126/science.6484569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissel J. P., Leizorovicz A., Picolet H., Peyrieux J. C. Secondary prevention after high-risk acute myocardial infarction with low-dose acebutolol. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Aug 1;66(3):251–260. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90831-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudoulas H., Rittgers S. E., Lewis R. P., Leier C. V., Weissler A. M. Changes in diastolic time with various pharmacologic agents: implication for myocardial perfusion. Circulation. 1979 Jul;60(1):164–169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutsaert D. L., Sys S. U., Gillebert T. C. Diastolic failure: pathophysiology and therapeutic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Jul;22(1):318–325. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90850-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bønaa K. H., Arnesen E. Association between heart rate and atherogenic blood lipid fractions in a population. The Tromsø Study. Circulation. 1992 Aug;86(2):394–405. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.2.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll J. D., Hess O. M., Hirzel H. O., Krayenbuehl H. P. Exercise-induced ischemia: the influence of altered relaxation on early diastolic pressures. Circulation. 1983 Mar;67(3):521–528. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.3.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copie X., Hnatkova K., Staunton A., Fei L., Camm A. J., Malik M. Predictive power of increased heart rate versus depressed left ventricular ejection fraction and heart rate variability for risk stratification after myocardial infarction. Results of a two-year follow-up study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Feb;27(2):270–276. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00454-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty A. H., Naccarelli G. V., Gray E. L., Hicks C. H., Goldstein R. A. Congestive heart failure with normal systolic function. Am J Cardiol. 1984 Oct 1;54(7):778–782. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(84)80207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer A. R., Persky V., Stamler J., Paul O., Shekelle R. B., Berkson D. M., Lepper M., Schoenberger J. A., Lindberg H. A. Heart rate as a prognostic factor for coronary heart disease and mortality: findings in three Chicago epidemiologic studies. Am J Epidemiol. 1980 Dec;112(6):736–749. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn E. J., Heesch C. M., Barnett J. H., Alvarez L. G., Fass S. M., Grayburn P. A., Hatfield B. A., Marcoux L. G., Malloy C. R. Effect of metoprolol on myocardial function and energetics in patients with nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Nov 1;24(5):1310–1320. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M. D., Alderman J. D., Aroesty J. M., Royal H. D., Ferguson J. J., Owen R. M., Grossman W., McKay R. G. Depression of systolic and diastolic myocardial reserve during atrial pacing tachycardia in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. J Clin Invest. 1988 Nov;82(5):1661–1669. doi: 10.1172/JCI113778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman W. H., Gabor R., Pepine C., Cavusoglu E. Heart rate reduction in the treatment of chronic stable angina pectoris: experiences with a sinus node inhibitor. Am Heart J. 1996 Jan;131(1):204–210. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(96)90075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frishman W. H., Pepine C. J., Weiss R. J., Baiker W. M. Addition of zatebradine, a direct sinus node inhibitor, provides no greater exercise tolerance benefit in patients with angina taking extended-release nifedipine: results of a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. The Zatebradine Study Group. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Aug;26(2):305–312. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)80000-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasser S. P., Michie D. D., Thadani U., Baiker W. M. Effects of zatebradine (ULFS 49 CL), a sinus node inhibitor, on heart rate and exercise duration in chronic stable angina pectoris. Zatebradine Investigators. Am J Cardiol. 1997 May 15;79(10):1401–1405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth B. D., Heusch G., Seitelberger R., Ross J., Jr Elimination of exercise-induced regional myocardial dysfunction by a bradycardiac agent in dogs with chronic coronary stenosis. Circulation. 1987 Mar;75(3):661–669. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.75.3.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guth B. D., Heusch G., Seitelberger R., Ross J., Jr Mechanism of beneficial effect of beta-adrenergic blockade on exercise-induced myocardial ischemia in conscious dogs. Circ Res. 1987 May;60(5):738–746. doi: 10.1161/01.res.60.5.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasenfuss G., Holubarsch C., Hermann H. P., Astheimer K., Pieske B., Just H. Influence of the force-frequency relationship on haemodynamics and left ventricular function in patients with non-failing hearts and in patients with dilated cardiomyopathy. Eur Heart J. 1994 Feb;15(2):164–170. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a060471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B., Kannel C., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Cupples L. A. Heart rate and cardiovascular mortality: the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1987 Jun;113(6):1489–1494. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90666-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjekshus J. Heart rate reduction--a mechanism of benefit? Eur Heart J. 1987 Dec;8 (Suppl 50):115–122. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/8.suppl_l.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ku D. N., Giddens D. P. Pulsatile flow in a model carotid bifurcation. Arteriosclerosis. 1983 Jan-Feb;3(1):31–39. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.3.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechat P., Escolano S., Golmard J. L., Lardoux H., Witchitz S., Henneman J. A., Maisch B., Hetzel M., Jaillon P., Boissel J. P. Prognostic value of bisoprolol-induced hemodynamic effects in heart failure during the Cardiac Insufficiency BIsoprolol Study (CIBIS). Circulation. 1997 Oct 7;96(7):2197–2205. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine H. J. Rest heart rate and life expectancy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Oct;30(4):1104–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangoni A. A., Mircoli L., Giannattasio C., Ferrari A. U., Mancia G. Heart rate-dependence of arterial distensibility in vivo. J Hypertens. 1996 Jul;14(7):897–901. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199607000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mensink G. B., Hoffmeister H. The relationship between resting heart rate and all-cause, cardiovascular and cancer mortality. Eur Heart J. 1997 Sep;18(9):1404–1410. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura T., Miyazaki S., Guth B. D., Indolfi C., Ross J., Jr Heart rate and force-frequency effects on diastolic function of the left ventricle in exercising dogs. Circulation. 1994 May;89(5):2361–2368. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.5.2361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulieri L. A., Hasenfuss G., Leavitt B., Allen P. D., Alpert N. R. Altered myocardial force-frequency relation in human heart failure. Circulation. 1992 May;85(5):1743–1750. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.85.5.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nul D. R., Doval H. C., Grancelli H. O., Varini S. D., Soifer S., Perrone S. V., Prieto N., Scapin O. Heart rate is a marker of amiodarone mortality reduction in severe heart failure. The GESICA-GEMA Investigators. Grupo de Estudio de la Sobrevida en la Insuficiencia Cardiaca en Argentina-Grupo de Estudios Multicéntricos en Argentina. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 May;29(6):1199–1205. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Packer M., Bristow M. R., Cohn J. N., Colucci W. S., Fowler M. B., Gilbert E. M., Shusterman N. H. The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure. U.S. Carvedilol Heart Failure Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1996 May 23;334(21):1349–1355. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199605233342101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panza J. A., Diodati J. G., Callahan T. S., Epstein S. E., Quyyumi A. A. Role of increases in heart rate in determining the occurrence and frequency of myocardial ischemia during daily life in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1992 Nov 1;20(5):1092–1098. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(92)90363-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perski A., Olsson G., Landou C., de Faire U., Theorell T., Hamsten A. Minimum heart rate and coronary atherosclerosis: independent relations to global severity and rate of progression of angiographic lesions in men with myocardial infarction at a young age. Am Heart J. 1992 Mar;123(3):609–616. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(92)90497-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pozzoli M., Traversi E., Cioffi G., Stenner R., Sanarico M., Tavazzi L. Loading manipulations improve the prognostic value of Doppler evaluation of mitral flow in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 1997 Mar 4;95(5):1222–1230. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.5.1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prabhu S. D., Freeman G. L. Left ventricular energetics in closed-chest dogs. Am J Physiol. 1993 Oct;265(4 Pt 2):H1048–H1055. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1993.265.4.H1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quyyumi A. A., Wright C. A., Mockus L. J., Fox K. M. Mechanisms of nocturnal angina pectoris: importance of increased myocardial oxygen demand in patients with severe coronary artery disease. Lancet. 1984 Jun 2;1(8388):1207–1209. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91693-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J., Jr, Miura T., Kambayashi M., Eising G. P., Ryu K. H. Adrenergic control of the force-frequency relation. Circulation. 1995 Oct 15;92(8):2327–2332. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.8.2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sa Cunha R., Pannier B., Benetos A., Siché J. P., London G. M., Mallion J. M., Safar M. E. Association between high heart rate and high arterial rigidity in normotensive and hypertensive subjects. J Hypertens. 1997 Dec;15(12 Pt 1):1423–1430. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Wannamethee G., Macfarlane P. W., Walker M. Heart rate, ischaemic heart disease, and sudden cardiac death in middle-aged British men. Br Heart J. 1993 Jul;70(1):49–55. doi: 10.1136/hrt.70.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suga H. Total mechanical energy of a ventricle model and cardiac oxygen consumption. Am J Physiol. 1979 Mar;236(3):H498–H505. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1979.236.3.H498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viscoli C. M., Horwitz R. I., Singer B. H. Beta-blockers after myocardial infarction: influence of first-year clinical course on long-term effectiveness. Ann Intern Med. 1993 Jan 15;118(2):99–105. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-118-2-199301150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamakawa H., Takeuchi M., Takaoka H., Hata K., Mori M., Yokoyama M. Negative chronotropic effect of beta-blockade therapy reduces myocardial oxygen expenditure for nonmechanical work. Circulation. 1996 Aug 1;94(3):340–345. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]