Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To determine the role of healed plaque disruption in the generation of chronic high grade coronary stenosis. METHODS—Coronary arteries obtained at necropsy were perfuse fixed with formal saline for 24 hours at 100 mg Hg. The percentage lumen diameter stenosis was measured in each 3 mm segment containing a plaque, using the lumen size at the nearest histologically normal segment as the reference point. Each segment was prepared for histological examination and stained with Sirius red and immunohistochemistry for smooth muscle actin. Healed disruption was considered to be present when under polarised light there was a break in the yellow-white dense collagen of the cap filled in by more loosely arranged green collagen. Increased smooth muscle density in the green staining areas was required. Each section was read independently by two observers; any segment with discordant views was considered negative. MATERIAL—31 men aged 51-69 dying suddenly of ischaemic heart disease. 39 coronary arteries were studied containing 256 separate plaques, after excluding coronary arteries with old total occlusions, an acute culprit thrombotic lesion, diffuse disease without normal arterial segments, and arteries related to old myocardial scars. RESULTS—16 of 99 plaques causing < 20% diameter stenosis had prior disruption. In the 21-50% stenosis range 16 of 86 plaques showed healed disruption. Stenosis ⩾ 51% by diameter was present in 71 plaques, 52 of which showed a healed disruption pattern. The difference between stenosis < 50% and stenosis ⩾ 51% was significant by the χ2 test (p < 0.001). CONCLUSIONS—Subclinical episodes of plaque disruption followed by healing are a stimulus to plaque growth that occurs suddenly and is a major factor in causing chronic high grade coronary stenosis. This mechanism would explain the phasic rather than linear progression of coronary disease observed in angiograms carried out annually in patients with chronic ischaemic heart disease. Keywords: atherosclerosis; stenosis; plaque disruption

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (128.3 KB).

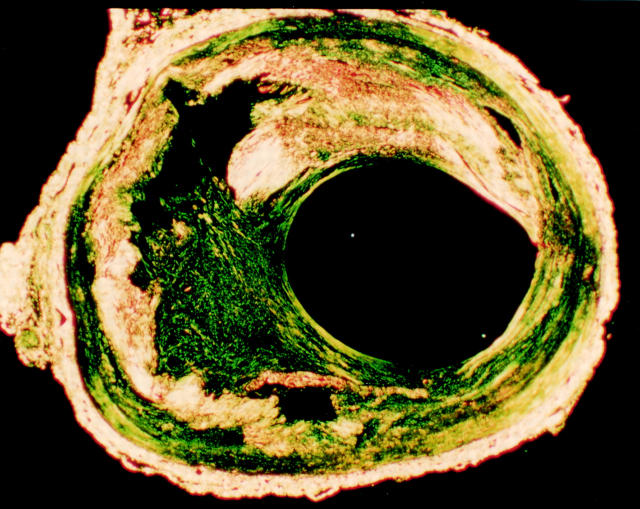

Figure 1 .

A cross section of a healed disruption in a human coronary plaque stained by Sirius red and viewed under polarised light. Much of the plaque collagen is yellow-white. A residual lipid core is present. Within the plaque cap there is a large defect filled with more loosely arranged green staining collagen.

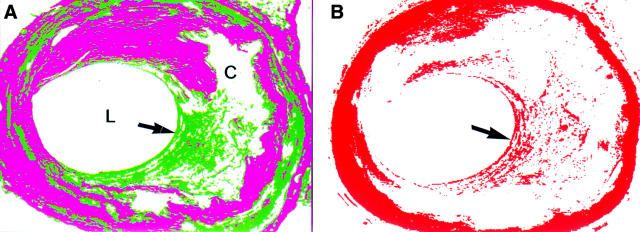

Figure 2 .

(A) Using image analysis and colour segmentation a computer image can be produced in which the dense older collagen is magenta in colour and the more loosely arranged collagen green (L, lumen; C, core). The area of healing in the cap (arrow) is clearly delineated. (B) Immunohistochemistry for smooth muscle actin (red). The media stains completely due to its smooth muscle content. In the area of healing of the plaque cap (arrow) there is an increased concentrate of smooth muscle cells.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alderman E. L., Corley S. D., Fisher L. D., Chaitman B. R., Faxon D. P., Foster E. D., Killip T., Sosa J. A., Bourassa M. G. Five-year angiographic follow-up of factors associated with progression of coronary artery disease in the Coronary Artery Surgery Study (CASS). CASS Participating Investigators and Staff. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Oct;22(4):1141–1154. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90429-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose J. A., Fuster V. The risk of coronary occlusion is not proportional to the prior severity of coronary stenoses. Heart. 1998 Jan;79(1):3–4. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose J. A., Tannenbaum M. A., Alexopoulos D., Hjemdahl-Monsen C. E., Leavy J., Weiss M., Borrico S., Gorlin R., Fuster V. Angiographic progression of coronary artery disease and the development of myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Jul;12(1):56–62. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrose J. A., Winters S. L., Arora R. R., Haft J. I., Goldstein J., Rentrop K. P., Gorlin R., Fuster V. Coronary angiographic morphology in myocardial infarction: a link between the pathogenesis of unstable angina and myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1985 Dec;6(6):1233–1238. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(85)80207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold A. E., Simoons M. L., Van de Werf F., de Bono D. P., Lubsen J., Tijssen J. G., Serruys P. W., Verstraete M. Recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator and immediate angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction. One-year follow-up. The European Cooperative Study Group. Circulation. 1992 Jul;86(1):111–120. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.86.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azen S. P., Mack W. J., Cashin-Hemphill L., LaBree L., Shircore A. M., Selzer R. H., Blankenhorn D. H., Hodis H. N. Progression of coronary artery disease predicts clinical coronary events. Long-term follow-up from the Cholesterol Lowering Atherosclerosis Study. Circulation. 1996 Jan 1;93(1):34–41. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.1.34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. L., Hibbs M. S., Kearney M., Loushin C., Isner J. M. Identification of 92-kD gelatinase in human coronary atherosclerotic lesions. Association of active enzyme synthesis with unstable angina. Circulation. 1995 Apr 15;91(8):2125–2131. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.8.2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruschke A. V., Kramer J. R., Jr, Bal E. T., Haque I. U., Detrano R. C., Goormastic M. The dynamics of progression of coronary atherosclerosis studied in 168 medically treated patients who underwent coronary arteriography three times. Am Heart J. 1989 Feb;117(2):296–305. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(89)90772-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Bland J. M., Hangartner J. R., Angelini A., Thomas A. C. Factors influencing the presence or absence of acute coronary artery thrombi in sudden ischaemic death. Eur Heart J. 1989 Mar;10(3):203–208. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a059467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J. Stability and instability: two faces of coronary atherosclerosis. The Paul Dudley White Lecture 1995. Circulation. 1996 Oct 15;94(8):2013–2020. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.8.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies M. J., Thomas A. C. Plaque fissuring--the cause of acute myocardial infarction, sudden ischaemic death, and crescendo angina. Br Heart J. 1985 Apr;53(4):363–373. doi: 10.1136/hrt.53.4.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escaned J., van Suylen R. J., MacLeod D. C., Umans V. A., de Jong M., Bosman F. T., de Feyter P. J., Serruys P. W. Histologic characteristics of tissue excised during directional coronary atherectomy in stable and unstable angina pectoris. Am J Cardiol. 1993 Jun 15;71(16):1442–1447. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(93)90609-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flugelman M. Y., Virmani R., Correa R., Yu Z. X., Farb A., Leon M. B., Elami A., Fu Y. M., Casscells W., Epstein S. E. Smooth muscle cell abundance and fibroblast growth factors in coronary lesions of patients with nonfatal unstable angina. A clue to the mechanism of transformation from the stable to the unstable clinical state. Circulation. 1993 Dec;88(6):2493–2500. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.6.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frink R. J. Chronic ulcerated plaques: new insights into the pathogenesis of acute coronary disease. J Invasive Cardiol. 1994 Jun;6(5):173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haft J. I., Haik B. J., Goldstein J. E., Brodyn N. E. Development of significant coronary artery lesions in areas of minimal disease. A common mechanism for coronary disease progression. Chest. 1988 Oct;94(4):731–736. doi: 10.1378/chest.94.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchins G. M., Bulkley B. H., Ridolfi R. L., Griffith L. S., Lohr F. T., Piasio M. A. Correlation of coronary arteriograms and left ventriculograms with postmortem studies. Circulation. 1977 Jul;56(1):32–37. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.56.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junqueira L. C., Bignolas G., Brentani R. R. Picrosirius staining plus polarization microscopy, a specific method for collagen detection in tissue sections. Histochem J. 1979 Jul;11(4):447–455. doi: 10.1007/BF01002772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafont A., Guzman L. A., Whitlow P. L., Goormastic M., Cornhill J. F., Chisolm G. M. Restenosis after experimental angioplasty. Intimal, medial, and adventitial changes associated with constrictive remodeling. Circ Res. 1995 Jun;76(6):996–1002. doi: 10.1161/01.res.76.6.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little W. C., Constantinescu M., Applegate R. J., Kutcher M. A., Burrows M. T., Kahl F. R., Santamore W. P. Can coronary angiography predict the site of a subsequent myocardial infarction in patients with mild-to-moderate coronary artery disease? Circulation. 1988 Nov;78(5 Pt 1):1157–1166. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.78.5.1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann J. M., Davies M. J. Assessment of the severity of coronary artery disease at postmortem examination. Are the measurements clinically valid? Br Heart J. 1995 Nov;74(5):528–530. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.5.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishioka T., Luo H., Eigler N. L., Berglund H., Kim C. J., Siegel R. J. Contribution of inadequate compensatory enlargement to development of human coronary artery stenosis: an in vivo intravascular ultrasound study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1996 Jun;27(7):1571–1576. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(96)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz J. N., Kong Y., Hackel D. B., Bartel A. G. Comparison of angiographic and postmortem findings in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1975 Aug;36(2):174–178. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(75)90522-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varnava A. Coronary artery remodelling. Heart. 1998 Feb;79(2):109–110. doi: 10.1136/hrt.79.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters D., Craven T. E., Lespérance J. Prognostic significance of progression of coronary atherosclerosis. Circulation. 1993 Apr;87(4):1067–1075. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.87.4.1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White C. J., Ramee S. R., Collins T. J., Escobar A. E., Karsan A., Shaw D., Jain S. P., Bass T. A., Heuser R. R., Teirstein P. S. Coronary thrombi increase PTCA risk. Angioscopy as a clinical tool. Circulation. 1996 Jan 15;93(2):253–258. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]