Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To determine the importance of the duration and intensity of "warm up" exercise for reducing ischaemia during second exercise in patients with exertional angina. DESIGN—Randomised crossover comparison of three warm up exercise protocols. PATIENTS—18 subjects with stable ischaemic heart disease and > 0.1 mV ST segment depression on treadmill exercise testing. INTERVENTIONS—The warm up protocols were 20 minutes of slow exercise at 2.7 km/h, symptom limited graded exercise for a mean of 7.4 (range 5.0 to 10.5) minutes, and three minutes of symptom limited fast exercise of similar maximum intensity. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES—ST segment depression during graded treadmill exercise undertaken 10 minutes after each warm up protocol or no warm up exercise. RESULTS—Compared with exercise with no warm up, the duration of graded exercise after earlier slow warm up increased by 4.9% (95% confidence interval (CI), −3.3% to 13.7%), after graded warm up by 10.3% (95% CI, 5.6% to 15.2%), and after fast warm up by 16% (95% CI, 6.2% to 26.7%). ST segment depression at equivalent submaximal exercise decreased after slow warm up by 27% (95% CI, 5% to 44%), after graded warm up by 31% (95% CI, 17% to 44%), and after fast warm up by 47% (95% CI, 27% to 61%). Compared with slow warm up exercise, the more intense graded and fast warm up protocols significantly increased the duration of second exercise (p = 0.0072) and reduced both peak ST depression (p = 0.0026) and the rate of increase of ST depression (p = 0.0069). CONCLUSIONS—In patients with exertional angina the size of the warm up response is related to the maximum intensity rather than the duration of first exercise. Keywords: exercise; angina; warm up; preconditioning

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (80.1 KB).

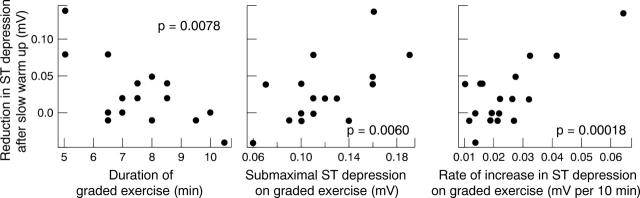

Figure 1 .

Mean percentage difference with 95% confidence intervals for graded exercise after slow, graded, and fast warm up protocols compared with graded exercise with no preceding warm up exercise.

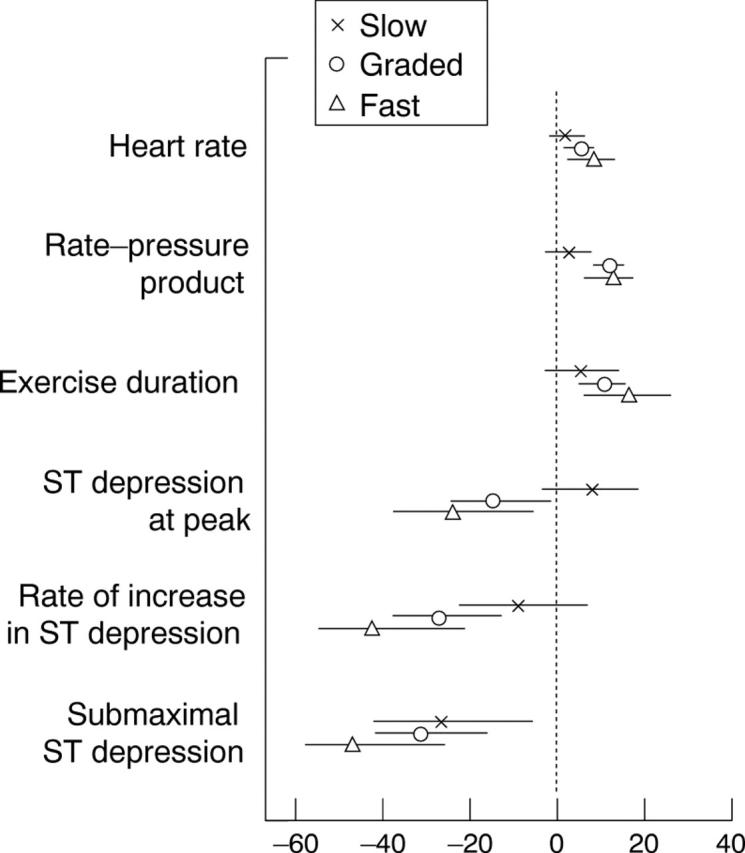

Figure 2 .

Relation between ST segment depression on graded exercise with no warm up and the magnitude of warm up induced by the slow exercise protocol. Warm up is measured as the reduction in ST depression at an equivalent submaximal stage of exercise; p values test if the slope of the regression line through the points on the plot is significantly different from zero.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blair S. N., Kohl H. W., 3rd, Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Clark D. G., Cooper K. H., Gibbons L. W. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989 Nov 3;262(17):2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBusk R. F., Stenestrand U., Sheehan M., Haskell W. L. Training effects of long versus short bouts of exercise in healthy subjects. Am J Cardiol. 1990 Apr 15;65(15):1010–1013. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)91005-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher G. F., Balady G., Froelicher V. F., Hartley L. H., Haskell W. L., Pollock M. L. Exercise standards. A statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Writing Group. Circulation. 1995 Jan 15;91(2):580–615. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hambrecht R., Niebauer J., Marburger C., Grunze M., Kälberer B., Hauer K., Schlierf G., Kübler W., Schuler G. Various intensities of leisure time physical activity in patients with coronary artery disease: effects on cardiorespiratory fitness and progression of coronary atherosclerotic lesions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Aug;22(2):468–477. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakicic J. M., Wing R. R., Butler B. A., Robertson R. J. Prescribing exercise in multiple short bouts versus one continuous bout: effects on adherence, cardiorespiratory fitness, and weight loss in overweight women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995 Dec;19(12):893–901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joy M., Cairns A. W., Sprigings D. Observations on the warm up phenomenon in angina pectoris. Br Heart J. 1987 Aug;58(2):116–121. doi: 10.1136/hrt.58.2.116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloner R. A., Bolli R., Marban E., Reinlib L., Braunwald E. Medical and cellular implications of stunning, hibernation, and preconditioning: an NHLBI workshop. Circulation. 1998 May 12;97(18):1848–1867. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.18.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marber M. S., Joy M. D., Yellon D. M. Is warm-up in angina ischaemic preconditioning? Br Heart J. 1994 Sep;72(3):213–215. doi: 10.1136/hrt.72.3.213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maybaum S., Ilan M., Mogilevsky J., Tzivoni D. Improvement in ischemic parameters during repeated exercise testing: a possible model for myocardial preconditioning. Am J Cardiol. 1996 Nov 15;78(10):1087–1091. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(96)90057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittleman M. A., Maclure M., Tofler G. H., Sherwood J. B., Goldberg R. J., Muller J. E. Triggering of acute myocardial infarction by heavy physical exertion. Protection against triggering by regular exertion. Determinants of Myocardial Infarction Onset Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1993 Dec 2;329(23):1677–1683. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris J. N., Clayton D. G., Everitt M. G., Semmence A. M., Burgess E. H. Exercise in leisure time: coronary attack and death rates. Br Heart J. 1990 Jun;63(6):325–334. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.6.325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niebauer J., Hambrecht R., Velich T., Hauer K., Marburger C., Kälberer B., Weiss C., von Hodenberg E., Schlierf G., Schuler G. Attenuated progression of coronary artery disease after 6 years of multifactorial risk intervention: role of physical exercise. Circulation. 1997 Oct 21;96(8):2534–2541. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor G. T., Buring J. E., Yusuf S., Goldhaber S. Z., Olmstead E. M., Paffenbarger R. S., Jr, Hennekens C. H. An overview of randomized trials of rehabilitation with exercise after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1989 Aug;80(2):234–244. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.80.2.234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki Y., Kodama K., Sato H., Kitakaze M., Hirayama A., Mishima M., Hori M., Inoue M. Attenuation of increased regional myocardial oxygen consumption during exercise as a major cause of warm-up phenomenon. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Jun;21(7):1597–1604. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90374-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldridge N. B., Guyatt G. H., Fischer M. E., Rimm A. A. Cardiac rehabilitation after myocardial infarction. Combined experience of randomized clinical trials. JAMA. 1988 Aug 19;260(7):945–950. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siscovick D. S., Weiss N. S., Fletcher R. H., Lasky T. The incidence of primary cardiac arrest during vigorous exercise. N Engl J Med. 1984 Oct 4;311(14):874–877. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198410043111402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart R. A., Simmonds M. B., Williams M. J. Time course of "warm-up" in stable angina. Am J Cardiol. 1995 Jul 1;76(1):70–73. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willich S. N., Lewis M., Löwel H., Arntz H. R., Schubert F., Schröder R. Physical exertion as a trigger of acute myocardial infarction. Triggers and Mechanisms of Myocardial Infarction Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1993 Dec 2;329(23):1684–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312023292302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto H., Tomoike H., Shimokawa H., Nabeyama S., Nakamura M. Development of collateral function with repetitive coronary occlusion in a canine model reduces myocardial reactive hyperemia in the absence of significant coronary stenosis. Circ Res. 1984 Nov;55(5):623–632. doi: 10.1161/01.res.55.5.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamanishi K., Fujita M., Ohno A., Sasayama S. Importance of myocardial ischaemia for recruitment of coronary collateral circulation in dogs. Cardiovasc Res. 1990 Apr;24(4):271–277. doi: 10.1093/cvr/24.4.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]