Abstract

BACKGROUND—With the increasing use of quality of life measures in evaluations of cardiac interventions, criteria are needed for selecting appropriate quality of life measures. An important criterion is the sensitivity of a measure for detecting clinically important changes. OBJECTIVES—To compare the sensitivity of four measures when used in a group of cardiac patients undergoing the same intervention. METHODS—The short form 36 (SF-36), the quality of life index-cardiac version (QLI), the quality of life after myocardial infarction questionnaire (QLMI), and the schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life (SEIQoL) were used to evaluate quality of life in a group of 22 patients after myocardial infarction or coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), at the beginning of rehabilitation and six weeks later. Analysable data were obtained from 16 patients. RESULTS—A significant improvement over time was only observed for the SF-36 subscale, vitality (p < 0.05). Five of the eight SF-36 subscales and one of the four QLMI subscales showed modest sensitivity (index: > 0.2 and < 0.5), while all other subscales showed poor sensitivity (index: < 0.2). Using SEIQoL, family was most often nominated as an area of importance to quality of life (n = 13), followed by health (n = 10), leisure/hobbies (n = 8), marriage (n = 8), and work (n = 6). CONCLUSIONS—All four QOL measures used in this study were found to lack sensitivity to change. Further research is needed using other cardiac populations and interventions in order to verify these findings, with a view to developing more sensitive quality of life scales. Keywords: quality of life; heart disease; short form 36; quality of life index-cardiac version; quality of life after myocardial infarction questionnaire; schedule for the evaluation of individual quality of life

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (115.0 KB).

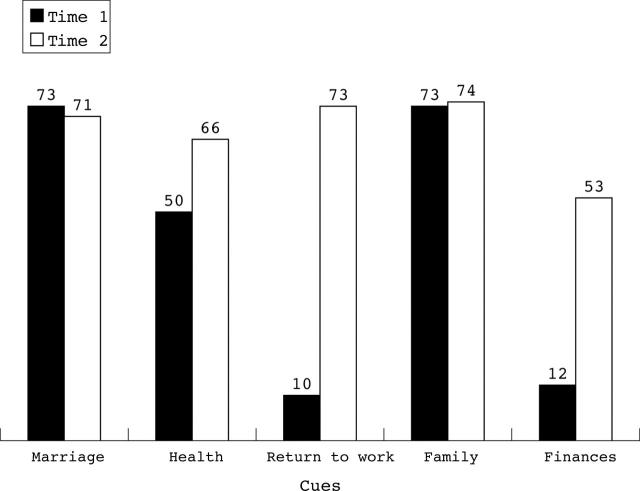

Figure 1 .

SEIQoL cue levels (on a scale of 0-100, where higher scores reflect higher quality of life) for one patient at time 1 and time 2. Cue weights at times 1 and 2: marriage 35%; health 30%; return to work 10%; family 20%; finances 5%.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Dougherty C. M., Dewhurst T., Nichol W. P., Spertus J. Comparison of three quality of life instruments in stable angina pectoris: Seattle Angina Questionnaire, Short Form Health Survey (SF-36), and Quality of Life Index-Cardiac Version III. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998 Jul;51(7):569–575. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00028-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrans C. E., Powers M. J. Quality of life index: development and psychometric properties. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 1985 Oct;8(1):15–24. doi: 10.1097/00012272-198510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill T. M., Feinstein A. R. A critical appraisal of the quality of quality-of-life measurements. JAMA. 1994 Aug 24;272(8):619–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt G. H., Naylor C. D., Juniper E., Heyland D. K., Jaeschke R., Cook D. J. Users' guides to the medical literature. XII. How to use articles about health-related quality of life. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 1997 Apr 16;277(15):1232–1237. doi: 10.1001/jama.277.15.1232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hickey A. M., Bury G., O'Boyle C. A., Bradley F., O'Kelly F. D., Shannon W. A new short form individual quality of life measure (SEIQoL-DW): application in a cohort of individuals with HIV/AIDS. BMJ. 1996 Jul 6;313(7048):29–33. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7048.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks F. D., Larson J. L., Ferrans C. E. Quality of life after liver transplant. Res Nurs Health. 1992 Apr;15(2):111–119. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770150205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillers T. K., Guyatt G. H., Oldridge N., Crowe J., Willan A., Griffith L., Feeny D. Quality of life after myocardial infarction. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994 Nov;47(11):1287–1296. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90134-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazis L. E., Anderson J. J., Meenan R. F. Effect sizes for interpreting changes in health status. Med Care. 1989 Mar;27(3 Suppl):S178–S189. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney C. A., Ware J. E., Jr, Lu J. F., Sherbourne C. D. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): III. Tests of data quality, scaling assumptions, and reliability across diverse patient groups. Med Care. 1994 Jan;32(1):40–66. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199401000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldridge N., Gottlieb M., Guyatt G., Jones N., Streiner D., Feeny D. Predictors of health-related quality of life with cardiac rehabilitation after acute myocardial infarction. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998 Mar-Apr;18(2):95–103. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199803000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D. L., Deyo R. A. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989 Mar;27(3 Suppl):S217–S232. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spertus J. A., Winder J. A., Dewhurst T. A., Deyo R. A., Fihn S. D. Monitoring the quality of life in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1994 Dec 15;74(12):1240–1244. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(94)90555-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor R., Kirby B., Burdon D., Caves R. The assessment of recovery in patients after myocardial infarction using three generic quality-of-life measures. J Cardiopulm Rehabil. 1998 Mar-Apr;18(2):139–144. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199803000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware J. E. Measuring patients' views: the optimum outcome measure. BMJ. 1993 May 29;306(6890):1429–1430. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6890.1429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]