Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To determine the cardiovascular and coronary risk thresholds at which aspirin for primary prevention of coronary heart disease is safe and worthwhile. DESIGN—Meta-analysis of four randomised controlled trials of aspirin for primary prevention. The benefit and harm from aspirin treatment were examined to determine: (1) the cardiovascular and coronary risk threshold at which benefit in prevention of myocardial infarction exceeds harm from significant bleeding; and (2) the absolute benefit expressed as number needed to treat (NNT) for aspirin net of cerebral haemorrhage and other bleeding complications at different levels of coronary risk. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES—Benefit from aspirin, expressed as reduction in cardiovascular events, myocardial infarctions, strokes, and total mortality; harm caused by aspirin in relation to significant bleeds and major haemorrhages. RESULTS—Aspirin for primary prevention significantly reduced all cardiovascular events by 15% (95% confidence interval (CI) 6% to 22%) and myocardial infarctions by 30% (95% CI 21% to 38%), and non-significantly reduced all deaths by 6% (95% CI −4% to 15%). Aspirin non-significantly increased strokes by 6% (95% CI −24% to 9%) and significantly increased bleeding complications by 69% (95% CI 38% to 107%). The risk of major bleeding balanced the reduction in cardiovascular events when cardiovascular event risk was 0.22%/year. The upper 95% CI for this estimate suggests that harm from aspirin is unlikely to outweigh benefit provided the cardiovascular event risk is 0.8%/year, equivalent to a coronary risk of 0.6%/year. At coronary event risk 1.5%/year, the five year NNT was 44 to prevent a myocardial infarction, and 77 to prevent a myocardial infarction net of any important bleeding complication. At coronary event risk 1%/year the NNT was 67 to prevent a myocardial infarction, and 182 to prevent a myocardial infarction net of important bleeding. CONCLUSIONS—Aspirin treatment for primary prevention is safe and worthwhile at coronary event risk ⩾ 1.5%/year; safe but of limited value at coronary risk 1%/year; and unsafe at coronary event risk 0.5%/year. Advice on aspirin for primary prevention requires formal accurate estimation of absolute coronary event risk. Keywords: aspirin; coronary heart disease; primary prevention; meta-analysis

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (1.2 MB).

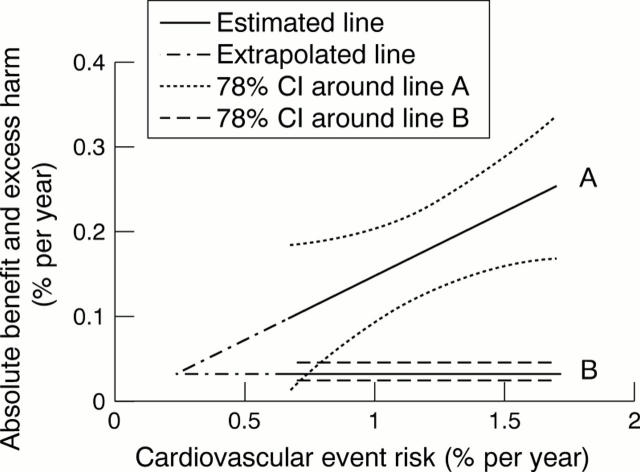

Figure 1 .

Absolute benefit (reduction in all cardiovascular events) (line A) and absolute harm (increase in major bleeds) (line B) from aspirin treatment, related to absolute cardiovascular event risk. The dotted lines show the 78% confidence regions. By extrapolation, benefit and harm from aspirin are equal when cardiovascular event risk is 0.22%/year, with an upper 95% confidence limit for this estimate at a cardiovascular event risk of approximately 0.8%/year.

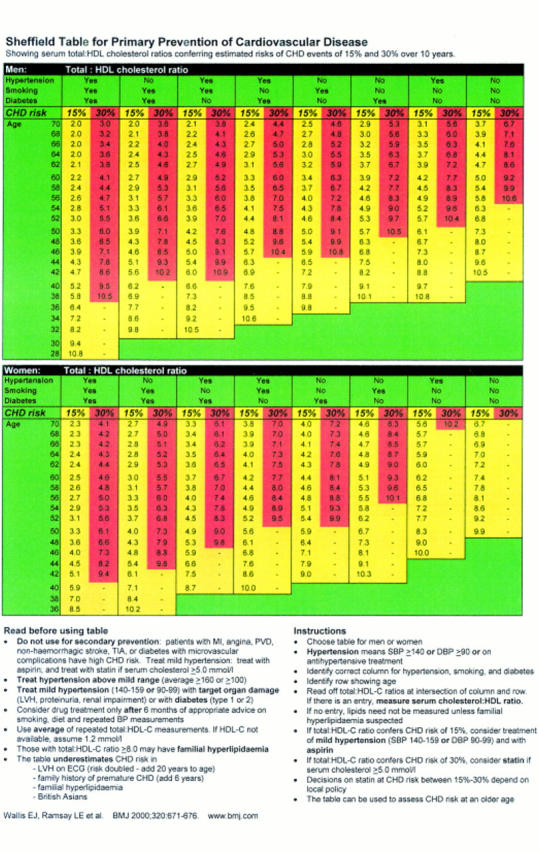

Figure 2 .

Sheffield table for primary prevention of cardiovascular diseases

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Altman D. G. Confidence intervals for the number needed to treat. BMJ. 1998 Nov 7;317(7168):1309–1312. doi: 10.1136/bmj.317.7168.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson K. M., Odell P. M., Wilson P. W., Kannel W. B. Cardiovascular disease risk profiles. Am Heart J. 1991 Jan;121(1 Pt 2):293–298. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90861-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissel J. P. Individualizing aspirin therapy for prevention of cardiovascular events. JAMA. 1998 Dec 9;280(22):1949–1950. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. A., Coupal L., Hu X. P. Identifying adults at increased risk of coronary disease. How well do the current cholesterol guidelines work? JAMA. 1995 Sep 13;274(10):801–806. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover S. A., Lowensteyn I., Esrey K. L., Steinert Y., Joseph L., Abrahamowicz M. Do doctors accurately assess coronary risk in their patients? Preliminary results of the coronary health assessment study. BMJ. 1995 Apr 15;310(6985):975–978. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6985.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansson L., Zanchetti A., Carruthers S. G., Dahlöf B., Elmfeldt D., Julius S., Ménard J., Rahn K. H., Wedel H., Westerling S. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998 Jun 13;351(9118):1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haq I. U., Ramsay L. E., Jackson P. R., Wallis E. J. Prediction of coronary risk for primary prevention of coronary heart disease: a comparison of methods. QJM. 1999 Jul;92(7):379–385. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.7.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J., Whelton P. K., Vu B., Klag M. J. Aspirin and risk of hemorrhagic stroke: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. JAMA. 1998 Dec 9;280(22):1930–1935. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.22.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hennekens C. H., Dyken M. L., Fuster V. Aspirin as a therapeutic agent in cardiovascular disease: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 1997 Oct 21;96(8):2751–2753. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.8.2751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isles C., Norrie J., Paterson J., Ritchie L. Risk of major gastrointestinal bleeding with aspirin. Lancet. 1999 Jan 9;353(9147):148–150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)76185-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly J. P., Kaufman D. W., Jurgelon J. M., Sheehan J., Koff R. S., Shapiro S. Risk of aspirin-associated major upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with enteric-coated or buffered product. Lancet. 1996 Nov 23;348(9039):1413–1416. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)01254-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kjeldsen S. E., Kolloch R. E., Leonetti G., Mallion J. M., Zanchetti A., Elmfeldt D., Warnold I., Hansson L. Influence of gender and age on preventing cardiovascular disease by antihypertensive treatment and acetylsalicylic acid. The HOT study. Hypertension Optimal Treatment. J Hypertens. 2000 May;18(5):629–642. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018050-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade T. W., Brennan P. J. Determination of who may derive most benefit from aspirin in primary prevention: subgroup results from a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2000 Jul 1;321(7252):13–17. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7252.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peto R., Gray R., Collins R., Wheatley K., Hennekens C., Jamrozik K., Warlow C., Hafner B., Thompson E., Norton S. Randomised trial of prophylactic daily aspirin in British male doctors. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1988 Jan 30;296(6618):313–316. doi: 10.1136/bmj.296.6618.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsay L. E., Williams B., Johnston G. D., MacGregor G. A., Poston L., Potter J. F., Poulter N. R., Russell G. British Hypertension Society guidelines for hypertension management 1999: summary. BMJ. 1999 Sep 4;319(7210):630–635. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7210.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis E. J., Ramsay L. E., Ul Haq I., Ghahramani P., Jackson P. R., Rowland-Yeo K., Yeo W. W. Coronary and cardiovascular risk estimation for primary prevention: validation of a new Sheffield table in the 1995 Scottish health survey population. BMJ. 2000 Mar 11;320(7236):671–676. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7236.671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weil J., Colin-Jones D., Langman M., Lawson D., Logan R., Murphy M., Rawlins M., Vessey M., Wainwright P. Prophylactic aspirin and risk of peptic ulcer bleeding. BMJ. 1995 Apr 1;310(6983):827–830. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6983.827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]