Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To develop and test a cardiac prevention and rehabilitation programme for achieving sustained lifestyle, risk factor, and therapeutic targets in patients presenting for the first time with exertional angina, acute coronary syndromes, or coronary revascularisation. DESIGN—A descriptive study. SETTING—A hospital based 12 week outpatient programme. INTERVENTIONS—A multiprofessional family based programme of lifestyle and risk factor modification. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES—Non-smoking status, body mass index, blood pressure, plasma cholesterol, use of prophylactic drugs. RESULTS—158 patients (82% of 194 possible cases) were recruited over 15 months, with 72% completing the programme. Targets for achieving non-smoking status, blood pressure < 140/90 mm Hg, and total cholesterol < 4.8 mmol/l were achieved in 92%, 73%, and 62%, respectively, and the proportion on aspirin, β blockers, and lipid lowering treatment was 95%, 58%, and 64% on referral back to general practice for continuing care. CONCLUSIONS—A comprehensive cardiac prevention and rehabilitation programme can be offered to all patients presenting for the first time with coronary heart disease, including those with exertional angina who are normally managed in primary care. Lifestyle, risk factor, and therapeutic targets can be successfully achieved in most patients with such a hospital based programme. Keywords: preventive policy; rehabilitation; coronary artery disease

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (147.8 KB).

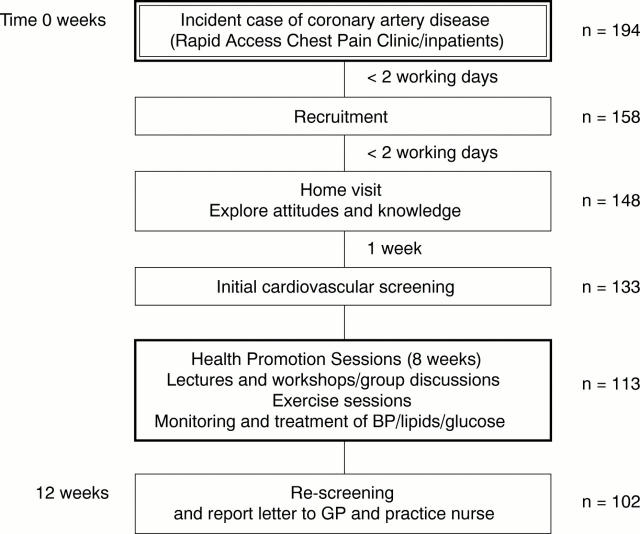

Figure 1 .

The Changes for Life programme and the flow of patients.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Campbell N. C., Ritchie L. D., Thain J., Deans H. G., Rawles J. M., Squair J. L. Secondary prevention in coronary heart disease: a randomised trial of nurse led clinics in primary care. Heart. 1998 Nov;80(5):447–452. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.5.447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A., Lloyd G., Weinman J., Jackson G. Why patients do not attend cardiac rehabilitation: role of intentions and illness beliefs. Heart. 1999 Aug;82(2):234–236. doi: 10.1136/hrt.82.2.234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cupples M. E., McKnight A. Randomised controlled trial of health promotion in general practice for patients at high cardiovascular risk. BMJ. 1994 Oct 15;309(6960):993–996. doi: 10.1136/bmj.309.6960.993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feder G., Griffiths C., Eldridge S., Spence M. Effect of postal prompts to patients and general practitioners on the quality of primary care after a coronary event (POST): randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999 Jun 5;318(7197):1522–1526. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7197.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freemantle N., Cleland J., Young P., Mason J., Harrison J. beta Blockade after myocardial infarction: systematic review and meta regression analysis. BMJ. 1999 Jun 26;318(7200):1730–1737. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7200.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gandhi M. M., Lampe F. C., Wood D. A. Incidence, clinical characteristics, and short-term prognosis of angina pectoris. Br Heart J. 1995 Feb;73(2):193–198. doi: 10.1136/hrt.73.2.193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jolly K., Bradley F., Sharp S., Smith H., Thompson S., Kinmonth A. L., Mant D. Randomised controlled trial of follow up care in general practice of patients with myocardial infarction and angina: final results of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). The SHIP Collaborative Group. BMJ. 1999 Mar 13;318(7185):706–711. doi: 10.1136/bmj.318.7185.706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law M., Tang J. L. An analysis of the effectiveness of interventions intended to help people stop smoking. Arch Intern Med. 1995 Oct 9;155(18):1933–1941. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackett D. L., Anderson G. D., Milner R., Feinleib M., Kannel W. B. Concordance for coronary risk factors among spouses. Circulation. 1975 Oct;52(4):589–595. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.52.4.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks F. M., Pfeffer M. A., Moye L. A., Rouleau J. L., Rutherford J. D., Cole T. G., Brown L., Warnica J. W., Arnold J. M., Wun C. C. The effect of pravastatin on coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events Trial investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996 Oct 3;335(14):1001–1009. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199610033351401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R. L., Pyke S. D., Scott E. A., Thompson S. G., Wood D. A. Dietary change after smoking cessation: a prospective study. Br J Nutr. 1995 Jul;74(1):27–38. doi: 10.1079/bjn19950104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Sleight P., Pogue J., Bosch J., Davies R., Dagenais G. Effects of an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, ramipril, on cardiovascular events in high-risk patients. The Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation Study Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2000 Jan 20;342(3):145–153. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001203420301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf S., Zucker D., Peduzzi P., Fisher L. D., Takaro T., Kennedy J. W., Davis K., Killip T., Passamani E., Norris R. Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet. 1994 Aug 27;344(8922):563–570. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]