Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To define the effects of β2 adrenergic receptor stimulation on ventricular repolarisation in vivo. DESIGN—Prospective study. SETTING—Tertiary referral centre. PATIENTS—85 patients with coronary artery disease and 22 normal controls. INTERVENTIONS—Intravenous and intracoronary salbutamol (a β2 adrenergic receptor selective agonist; 10-30 µg/min and 1-10 µg/min), and intravenous isoprenaline (a mixed β1/β2 adrenergic receptor agonist; 1-5 µg/min), infused during fixed atrial pacing. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES—QT intervals, QT dispersion, monophasic action potential duration. RESULTS—In patients with coronary artery disease, salbutamol decreased QTonset and QTpeak but increased QTend duration; QTonset-QTpeak and QTpeak-QTend intervals increased, resulting in T wave prolongation (mean (SEM): 201 (2) ms to 233 (2) ms; p < 0.01). There was a large increase in dispersion of QTonset, QTpeak, and QTend which was more pronounced in patients with coronary artery disease—for example, QTend dispersion: 50 (2) ms baseline v 98 (4) ms salbutamol (controls), and 70 (1) ms baseline v 108 (3) ms salbutamol (coronary artery disease); p < 0.001. Similar responses were obtained with isoprenaline. Monophasic action potential duration at 90% repolarisation shortened during intracoronary infusion of salbutamol, from 278 (4.1) ms to 257 (3.8) ms (p < 0.05). CONCLUSIONS—β2 adrenergic receptors mediate important electrophysiological effects in human ventricular myocardium. The increase in dispersion of repolarisation provides a mechanism whereby catecholamines acting through this receptor subtype may trigger ventricular arrhythmias. Keywords: β2 adrenergic receptors; ventricular repolarisation; QT dispersion; salbutamol; isoprenaline

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (157.1 KB).

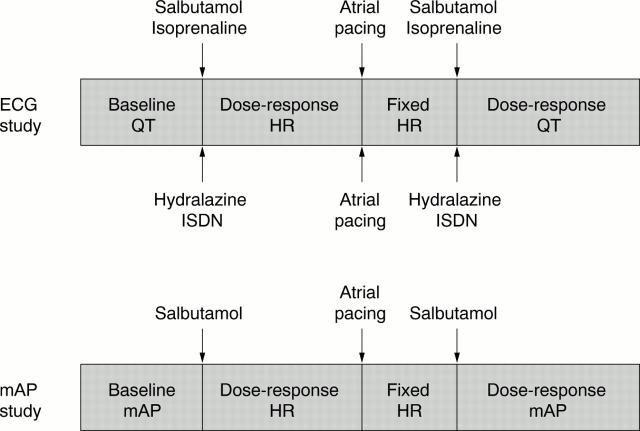

Figure 1 .

Experimental protocols for infusion schedules, ECG, and monophasic action potential (mAP) data collection. See text for details. HR, heart rate; ISDN, isosorbide dinitrate.

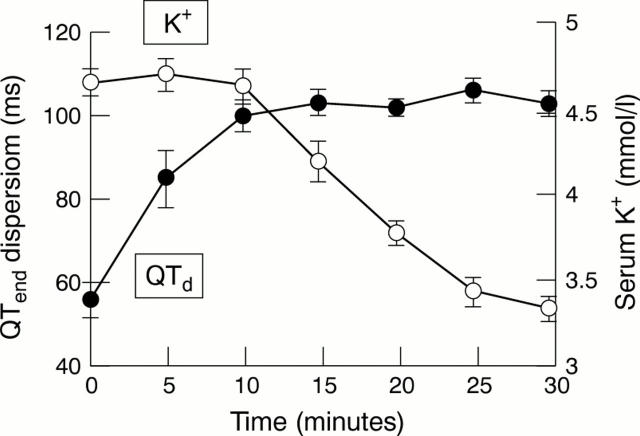

Figure 2 .

Blood pressure responses following (A) intravenous salbutamol (0-30 µg/min) and (B) intravenous isoprenaline (0-5 µg/min). Systolic, diastolic, and mean blood pressure responses are shown.

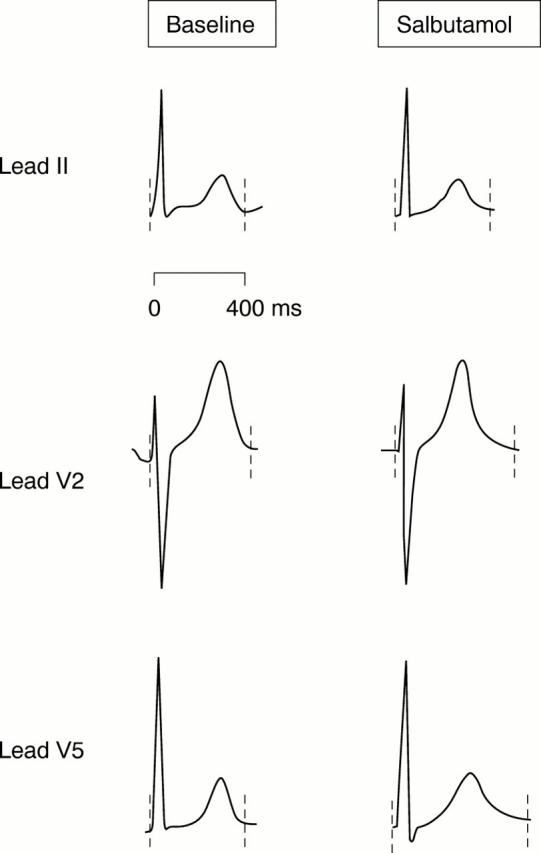

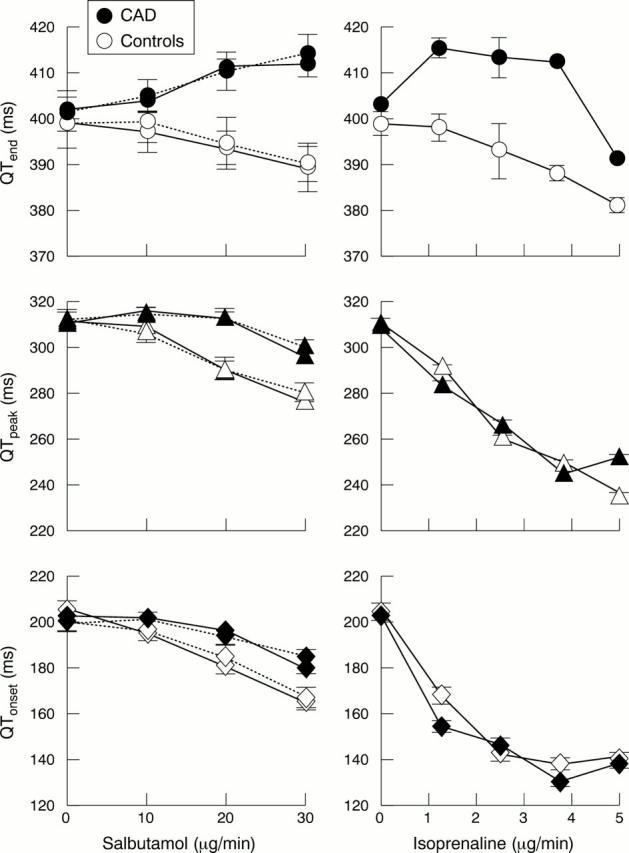

Figure 3 .

Typical ECG recordings obtained during fixed atrial pacing at baseline (left) and with intravenous salbutamol (30 µg/min) (right). QTend interval for each ECG complex indicated by broken lines.

Figure 4 .

Changes in mean QTend, QTpeak, and QTonset during salbutamol infusion (0-30 µg/min) (left panel) and isoprenaline infusion (0-5 µg/min) (right panel). Responses have been separated for patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) and controls, and those taking (broken lines) and not taking (unbroken lines) atenolol. There is a dose dependent decrease in QTonset and QTpeak, but an increase in QTend in coronary artery disease patients.

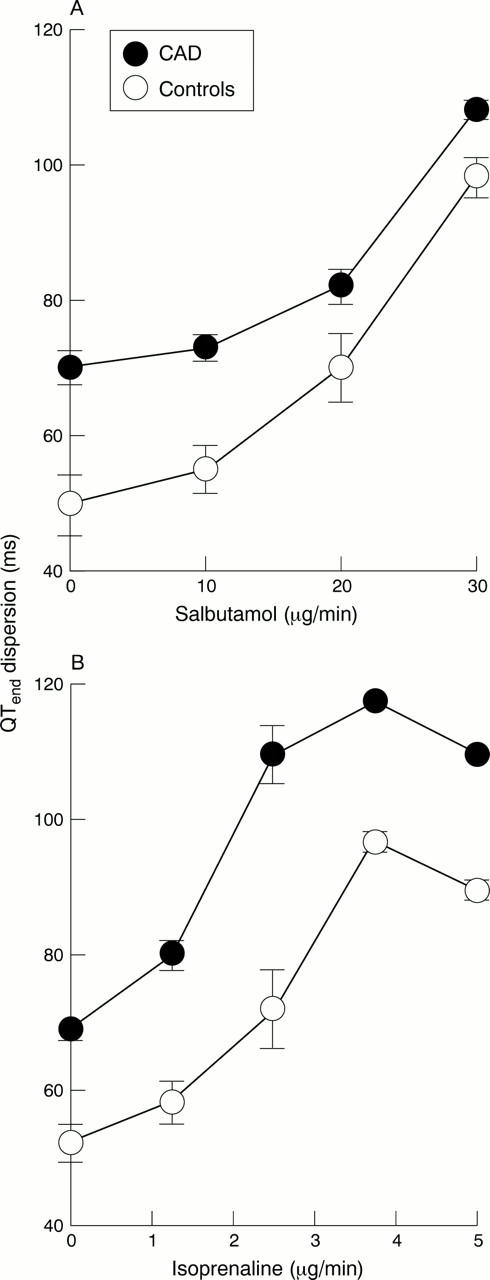

Figure 5 .

Changes in QTend dispersion following (A) intravenous salbutamol and (B) intravenous isoprenaline. There are large increases in QT dispersion following both salbutamol and isoprenaline in coronary artery disease and control patients.

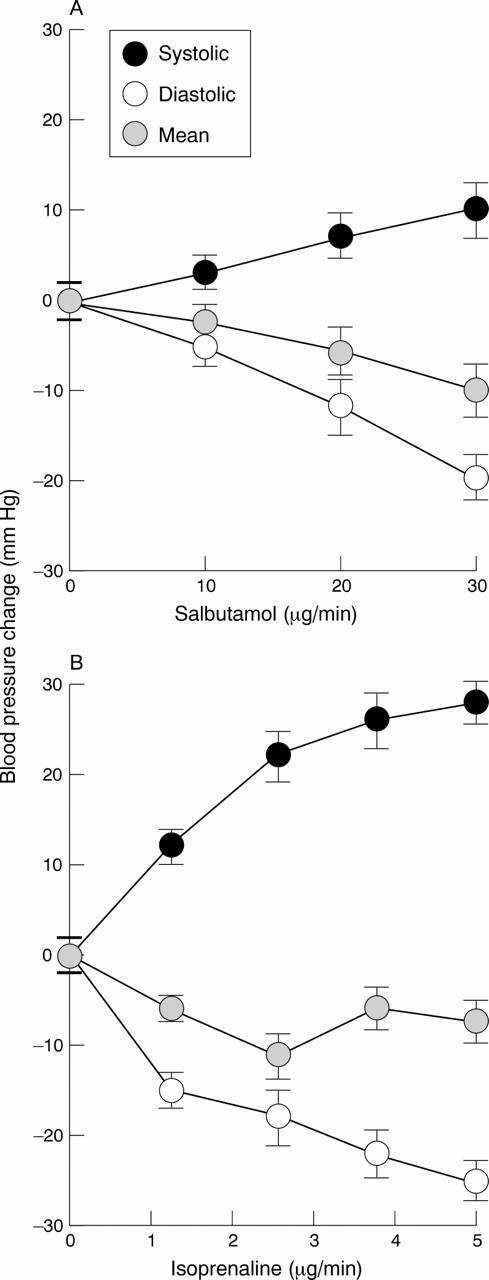

Figure 6 .

Changes in QTend dispersion (QTd) and serum potassium (K+) during initial high dose intravenous infusion of salbutamol. There is a pronounced increase in QTd before any significant decrease in serum potassium.

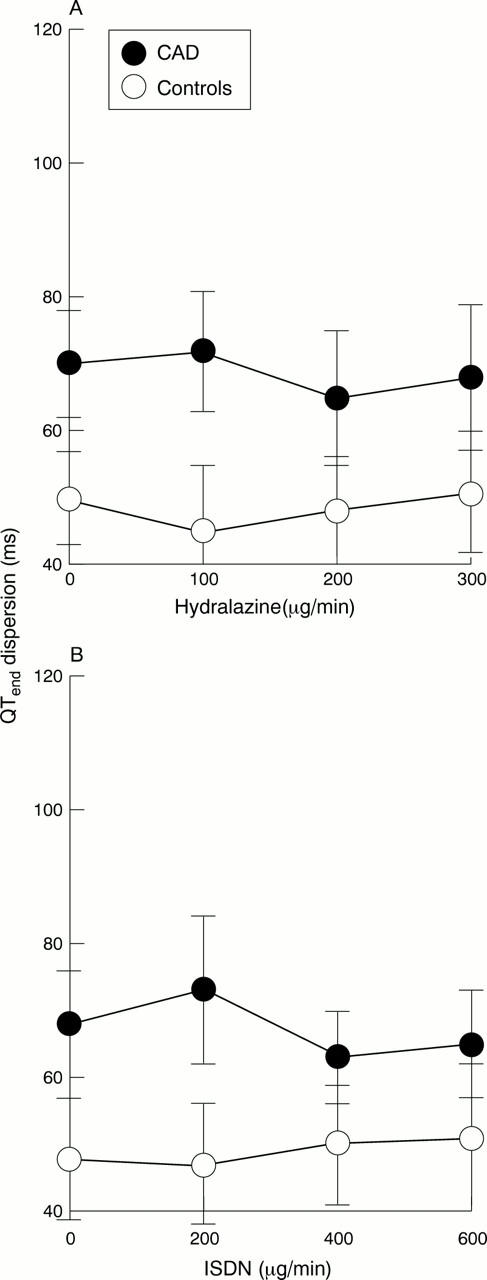

Figure 7 .

QTend dispersion following (A) intravenous hydralazine (0-300 µg/min) and (B) intravenous isosorbide dinitrate (ISDN) (0-600 µg/min). There were no significant changes seen during infusion with either agent.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barr C. S., Naas A., Freeman M., Lang C. C., Struthers A. D. QT dispersion and sudden unexpected death in chronic heart failure. Lancet. 1994 Feb 5;343(8893):327–329. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91164-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biberman L., Sarma R. N., Surawicz B. T-wave abnormalities during hyperventilation and isoproterenol infusion. Am Heart J. 1971 Feb;81(2):166–174. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(71)90127-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billman G. E., Castillo L. C., Hensley J., Hohl C. M., Altschuld R. A. Beta2-adrenergic receptor antagonists protect against ventricular fibrillation: in vivo and in vitro evidence for enhanced sensitivity to beta2-adrenergic stimulation in animals susceptible to sudden death. Circulation. 1997 Sep 16;96(6):1914–1922. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bristow M. R., Hershberger R. E., Port J. D., Gilbert E. M., Sandoval A., Rasmussen R., Cates A. E., Feldman A. M. Beta-adrenergic pathways in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 1990 Aug;82(2 Suppl):I12–I25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud F. S., Surawicz B., Gettes L. S. Effect of isoproterenol on the abnormal T wave. Am J Cardiol. 1972 Dec;30(8):810–819. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(72)90004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day C. P., McComb J. M., Campbell R. W. QT dispersion: an indication of arrhythmia risk in patients with long QT intervals. Br Heart J. 1990 Jun;63(6):342–344. doi: 10.1136/hrt.63.6.342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz M. R. Method and theory of monophasic action potential recording. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1991 May-Jun;33(6):347–368. doi: 10.1016/0033-0620(91)90002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAN J., GARCIADEJALON P., MOE G. K. ADRENERGIC EFFECTS ON VENTRICULAR VULNERABILITY. Circ Res. 1964 Jun;14:516–524. doi: 10.1161/01.res.14.6.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A., Kaumann A. J., Brown M. J. Selective beta 1-adrenoceptor blockade enhances positive inotropic responses to endogenous catecholamines mediated through beta 2-adrenoceptors in human atrial myocardium. Circ Res. 1990 Jun;66(6):1610–1623. doi: 10.1161/01.res.66.6.1610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A., Petch M. C., Brown M. J. In vivo demonstration of cardiac beta 2-adrenoreceptor sensitization by beta 1-antagonist treatment. Circ Res. 1991 Oct;69(4):959–964. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall J. A., Petch M. C., Brown M. J. Intracoronary injections of salbutamol demonstrate the presence of functional beta 2-adrenoceptors in the human heart. Circ Res. 1989 Sep;65(3):546–553. doi: 10.1161/01.res.65.3.546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel P. A. Seminars in medicine of the Beth Israel Hospital, Boston. Adrenergic receptors--evolving concepts and clinical implications. N Engl J Med. 1996 Feb 29;334(9):580–585. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsberg R. P., Cryer P. E., Roberts R. Serial plasma catecholamine response early in the course of clinical acute myocardial infarction: relationship to infarct extent and mortality. Am Heart J. 1981 Jul;102(1):24–29. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(81)90408-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann A. J., Lemoine H. Beta 2-adrenoceptor-mediated positive inotropic effect of adrenaline in human ventricular myocardium. Quantitative discrepancies with binding and adenylate cyclase stimulation. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1987 Apr;335(4):403–411. doi: 10.1007/BF00165555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann A. J., Sanders L. Both beta 1- and beta 2-adrenoceptors mediate catecholamine-evoked arrhythmias in isolated human right atrium. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1993 Nov;348(5):536–540. doi: 10.1007/BF00173215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaumann A., Bartel S., Molenaar P., Sanders L., Burrell K., Vetter D., Hempel P., Karczewski P., Krause E. G. Activation of beta2-adrenergic receptors hastens relaxation and mediates phosphorylation of phospholamban, troponin I, and C-protein in ventricular myocardium from patients with terminal heart failure. Circulation. 1999 Jan 5;99(1):65–72. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall M. J., Lynch K. P., Hjalmarson A., Kjekshus J. Beta-blockers and sudden cardiac death. Ann Intern Med. 1995 Sep 1;123(5):358–367. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-5-199509010-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. S., Munakata K., Reddy C. P., Surawicz B. Characteristics and possible mechanism of ventricular arrhythmia dependent on the dispersion of action potential durations. Circulation. 1983 Jun;67(6):1356–1367. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.67.6.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lechat P., Packer M., Chalon S., Cucherat M., Arab T., Boissel J. P. Clinical effects of beta-adrenergic blockade in chronic heart failure: a meta-analysis of double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trials. Circulation. 1998 Sep 22;98(12):1184–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.12.1184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B. T., Frame L. H., Molinoff P. B. Beta 2-adrenergic receptors contribute to catecholamine-stimulated shortening of action potential duration in dog atrial muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jul;82(13):4521–4525. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.13.4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCaffrey P. M., Riddell J. G., Shanks R. G. Selectivity of xamoterol, prenalterol and salbutamol as assessed by their effects in the presence and absence of ICI 118 551. Eur Heart J. 1990 Apr;11 (Suppl A):54–55. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/11.suppl_a.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merx W., Yoon M. S., Han J. The role of local disparity in conduction and recovery time on ventricular vulnerability to fibrillation. Am Heart J. 1977 Nov;94(5):603–610. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(77)80130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mettauer B., Rouleau J. L., Burgess J. H. Detrimental arrhythmogenic and sustained beneficial hemodynamic effects of oral salbutamol in patients with chronic congestive heart failure. Am Heart J. 1985 Apr;109(4):840–847. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90648-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morady F., Nelson S. D., Kou W. H., Pratley R., Schmaltz S., De Buitleir M., Halter J. B. Electrophysiologic effects of epinephrine in humans. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988 Jun;11(6):1235–1244. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(88)90287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss A. J., Zareba W., Benhorin J., Locati E. H., Hall W. J., Robinson J. L., Schwartz P. J., Towbin J. A., Vincent G. M., Lehmann M. H. ECG T-wave patterns in genetically distinct forms of the hereditary long QT syndrome. Circulation. 1995 Nov 15;92(10):2929–2934. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.10.2929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motomura S., Reinhard-Zerkowski H., Daul A., Brodde O. E. On the physiologic role of beta-2 adrenoceptors in the human heart: in vitro and in vivo studies. Am Heart J. 1990 Mar;119(3 Pt 1):608–619. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(05)80284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton G. E., Azevedo E. R., Parker J. D. Inotropic and sympathetic responses to the intracoronary infusion of a beta2-receptor agonist: a human in vivo study. Circulation. 1999 May 11;99(18):2402–2407. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.18.2402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perkiömäki J. S., Koistinen M. J., Yli-Mäyry S., Huikuri H. V. Dispersion of QT interval in patients with and without susceptibility to ventricular tachyarrhythmias after previous myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Jul;26(1):174–179. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00122-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schäfers R. F., Adler S., Daul A., Zeitler G., Vogelsang M., Zerkowski H. R., Brodde O. E. Positive inotropic effects of the beta 2-adrenoceptor agonist terbutaline in the human heart: effects of long-term beta 1-adrenoceptor antagonist treatment. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Apr;23(5):1224–1233. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomaselli G. F., Beuckelmann D. J., Calkins H. G., Berger R. D., Kessler P. D., Lawrence J. H., Kass D., Feldman A. M., Marban E. Sudden cardiac death in heart failure. The role of abnormal repolarization. Circulation. 1994 Nov;90(5):2534–2539. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.5.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wit A. L., Hoffman B. F., Rosen M. R. Electrophysiology and pharmacology of cardiac arrhythmias. IX. Cardiac electrophysiologic effects of beta adrenergic receptro stimulation and blockade. Part C. Am Heart J. 1975 Dec;90(6):795–803. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(75)90471-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao R. P., Lakatta E. G. Beta 1-adrenoceptor stimulation and beta 2-adrenoceptor stimulation differ in their effects on contraction, cytosolic Ca2+, and Ca2+ current in single rat ventricular cells. Circ Res. 1993 Aug;73(2):286–300. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M., Klingenheben T., Franz M. R., Hohnloser S. H. Assessment of QT dispersion for prediction of mortality or arrhythmic events after myocardial infarction: results of a prospective, long-term follow-up study. Circulation. 1998 Jun 30;97(25):2543–2550. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabel M., Portnoy S., Franz M. R. Electrocardiographic indexes of dispersion of ventricular repolarization: an isolated heart validation study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Mar 1;25(3):746–752. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00446-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipes D. P. Sympathetic stimulation and arrhythmias. N Engl J Med. 1991 Aug 29;325(9):656–657. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108293250911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bruyne M. C., Hoes A. W., Kors J. A., Hofman A., van Bemmel J. H., Grobbee D. E. QTc dispersion predicts cardiac mortality in the elderly: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 1998 Feb 10;97(5):467–472. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.5.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]