Abstract

Hypoxia activates a number of gene products through degradation of the transcriptional coactivator cAMP response element binding protein (CREB). Other transcriptional regulators (e.g., β-catenin and NF-κB) are controlled through phosphorylation-targeted proteasomal degradation, and thus, we hypothesized a similar degradative pathway for CREB. Differential display analysis of mRNA derived from hypoxic epithelia revealed a specific and time-dependent repression of protein phosphatase 1 (PP1), a serine phosphatase important in CREB dephosphorylation. Subsequent studies identified a previously unappreciated proteasomal-targeting motif within the primary structure of CREB (DSVTDS), which functions as a substrate for PP1. Ambient hypoxia resulted in temporally sequential CREB serine phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation (in vitro and in vivo). HIV-tat peptide-facilitated loading of intact epithelia with phosphopeptides corresponding to this proteasome targeting motif resulted in inhibition of CREB ubiquitination. Further studies revealed that PP1 inhibitors mimicked hypoxia-induced gene expression, whereas proteasome inhibitors reversed the hypoxic phenotype. Thus, hypoxia establishes conditions that target CREB to proteasomal degradation. These studies may provide unique insight into a general mechanism of transcriptional regulation by hypoxia.

Diminished tissue oxygen supply (hypoxia) is a common physiologic and pathophysiologic occurrence (1). Consequently, adaptation to hypoxia has been a major goal of evolutionary development (2). Transcriptional responses to hypoxia may result in the induction of adaptive or inflammatory cellular phenotypes (1). Adaptive responses to hypoxia generally are mediated by the hypoxia-inducible factor 1 transcriptional regulator (3–5). Alternatively, activation of NF-κB and repression of the cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) together mediate induction of an hypoxia-elicited proinflammatory phenotype (1, 6, 7). Pathways that regulate CREB expression remain unclear.

Proteasomal degradation represents a primary mechanism of controlled proteolysis and is necessary for cellular function and viability (8, 9). Targeted proteasomal degradation is important in the regulated expression of a number of transcription factors including activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2; refs. 10 and 11), hypoxia inducible factor-1 (12, 13), and NF-κB (14). For example, activation of NF-κB signaling depends on the proteasomal degradation of its inhibitory subunit, IκB. A specific recognition motif in IκB is phosphorylated before degradation and represents a specific targeting mechanism to ubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal degradation (14, 15). A similar targeting sequence exists within the primary structure of the transcriptional regulator β-catenin (16). This work revealed a distinct class of E3 ubiquitin ligases, termed SCF (Skp1-Cullin-1/Cdc53-Fbox) complexes, composed of the subunits Skp1, Rbx1, and Cdc53 and any of a large number of Fbox proteins (17, 18).

We investigated the impact of hypoxia on phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and degradation of CREB. We demonstrate that CREB shares a homologous targeting motif with IκB and β-catenin (15). This motif is dephosphorylated by members of the protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) family. Furthermore, hypoxia specifically depletes PP1 levels, resulting in hyperphosphorylation, ubiquitination, and proteasomal degradation of CREB. These studies reveal a targeting mechanism by which regulatory proteins may be deployed specifically toward degradation under conditions of cellular hypoxia.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Hypoxia.

T84 cells were maintained as described (19, 20). Exposure to hypoxia was performed as described (6) by using standard hypoxic conditions [pO2 20 torr (1 torr = 133 Pa), pCO2 35 torr, with a balance of N2 and water vapor]. Normoxic controls were exposed to the same experimental protocols under conditions of atmospheric O2 concentrations (pO2 147 torr and pCO2 35 torr).

Differential mRNA Analysis.

T84 cells were exposed to hypoxia (0, 8, and 16 h). Total RNA was extracted as described (7). Two approaches were used to examine differentially expressed genes. First, stable cDNA fragments were generated by using the Heiroglyph mRNA profile system (Becton Coulter), and cDNA fragments were resolved by high-resolution electrophoresis. HeLa cell RNA functioned as a control. Fluorescently tagged cDNA was scanned by using a Genomyx SC fluorescent scanner (Genomyx, Foster City, CA), and bands were excised, reamplified by PCR, and sequenced. Second, the transcriptional profile was assessed by using quantitative genechip expression arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA; ref. 21).

Analysis of mRNA Levels by PCR.

Total cellular RNA was obtained and purified as described above, and reverse transcription–PCR analysis was performed as described (7). The PCR for human PP1γ contained 50 pM each of the sense primer (5′-AGTTTGACAATGCAGGTGCC-3′) and the antisense primer (3′-GCTTTGTGATCATACCCCTTGG-5′), 1 μl of cDNA from the reverse transcriptase reaction, 76 μl of DEPC H2O, 10 μl of 10× reaction mix buffer [100 mM KCl/100 mM (NH4)2SO4/100 mM Tris, pH 8.8/20 mM MgSO4] 2 μl of dNTP (0.2 mM each), and 1 μl of 50× advantage polymerase mix. The amplification reaction included a 3-min denaturation at 95°C, followed by 26–32 cycles at 94°C for 30 sec, 60°C for 30 sec, and 72°C for 1 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Human β-actin was used as a control for each amplification, with sense (5′-TGACGGGGTCACCCACACTGTGCCCATCTA-3′) and antisense primer (5′-CTAGAAGCATTTGCGGTGGACGATGGAGGG-3′) in identical reactions (661-bp-amplified fragment).

Western Blotting.

Whole-cell extracts (for examination of CREB) were prepared as described (7). For Western blotting, anti-CREB (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY), anti-PP1γ (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), anti-phosphoserine (Zymed), or antiubiquitin (StressGen Biotechnologies, Victoria, Canada) were added for 3 h; blots were washed; and species-matched peroxidase-conjugated secondary Ab was added (Cappell) as described (22). Labeled bands were detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham Pharmacia).

Phosphopeptide Treatment.

HIV-tat peptide-facilitated loading of cells with phosphopeptides was performed as described (23, 24), with modifications. Synthetic peptides were generated by Synpep Corporation (Dublin, CA). Peptide sequences were HIV-tat peptide, YGRKKRRQRRRG; unphosphorylated CREB targeting sequence, VDSVTDSQKR; single-phosphorylated CREB targeting sequence, VDS(PO3)VTDSQKR; double-phosphorylated CREB targeting sequence, VDS(PO3)VTDS(PO3)QKR; or scrambled peptide control, STKVDSQRDV. All peptides were made as stock concentration of 10 mM in DMSO. Equimolar concentrations of HIV-tat peptide and test peptide were coincubated for 10 min before addition to cells. Peptides (final concentration 10 μM) were added apically by using equivolume DMSO as a vehicle control, and peptides were incubated with cells for 15 min before cell incubation in hypoxia.

Phosphatase Assay.

PP1-dependent dephosphorylation of peptide sequences was estimated by using a phosphatase assay (Upstate Biotechnology). Peptides were coincubated for 30 min with purified PP1 in the presence and absence of the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and calyculin A. After incubation, malachite green solution was used to detect free phosphate generated as a result of phosphatase activity. An internal phosphopeptide control was used.

To investigate the dephosphorylation of synthetic phosphopeptides by normoxic and hypoxic cell lysates, HPLC was used. Briefly, T84 cells were exposed to hypoxia (24 h) and washed in ice cold PBS, and cell lysates were prepared by sonication. The double-phosphorylated peptide (10 μM) was added to the lysates and brought to 37°C, and the reaction was allowed to continue for 5 min (optimized from pilot experiments) before termination by snap freezing in liquid nitrogen. Lysate/peptide mixes were thawed, and the profile of phosphopeptides remaining was determined by HPLC. Peptide levels were measured with a 10–90% (vol/vol) H2O/CH3CN gradient (30 min) mobile phase (1 ml/min) on a reverse-phase HPLC column (Luna 5-μ C18, 150 × 4.6 mm; Phenomenex, Torrence, CA). Absorbance was monitored at 220 nm. UV absorption spectra were collected, and peptides were identified by their chromatographic elements (retention time, UV spectra, and coelution with standards).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbant Assays (ELISAs).

Cells grown on 5-cm2 permeable membrane supports were treated with hypoxia (as described in Cell Culture and Hypoxia), okadaic acid (0–1 μM), calyculin A (0–300 nM), lactacystin (0–10 nM), N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-Methioninal (ALLM; 100 μM), or N-acetyl-Leu-Leu-norleucinal (ALLN; 100 μM). Basolateral supernatants were collected, cellular debris was removed by centrifugation, and cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) levels were quantified by capture ELISA as described (6, 25).

Generation of Retroviral CREB-Overexpressing Cells.

As described (7), retroviral-mediated gene transfer of T84 cells with CREB and mutant CREB [S → A mutation at position 133, the protein kinase (PKA) phosphorylation site, a kind gift from Dr. Marc Montminy, Salk Institute, La Jolla, CA] was performed (26) .

Animal Model of Hypoxia.

In experiments investigating whole animal hypoxia, mice were exposed to 8% oxygen (balance N2) for 6 h. After mice were killed, colonic tissue was removed and dissected at the mesenteric border, and mucosal scrapings were made by using a spatula. This protocol was in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of live animals and was approved by institutional animal care and use committee at Brigham and Women's hospital. Mucosal scrapings were resuspended in Western blot lysis buffer, vortex mixed, and incubated end-over-end for 1 h before centrifugation (16,000 × g for 5 min). Supernatants were removed for analysis of CREB by immunoprecipitation/Western blotting.

CREB-Dependent Reporter Gene Assay.

Caco-2 cells were grown to ≈80% confluence on Petri dishes and transfected with a reporter plasmid containing the luciferase reporter gene under the control of a basic promoter element (TATA) plus a defined inducible cis-enhancer element containing four cAMP response element (CRE) motifs (Stratagene). Where indicated, cells were also cotransfected with a plasmid containing the cAMP-dependent PKA gene. Transfections were performed overnight by using Effectene transfection reagent (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). After transfection, cells were exposed to hypoxia (0–48 h), and where indicated, were exposed to forskolin (10 μM; or DMSO vehicle control) for 6 h. Luciferase activity was assessed (Topcount-NXT; Packard), in all cells by using a luciferase assay kit (Stratagene).

Data Presentation.

Cytokine ELISA data were compared by one-way ANOVA and by Student's t test with P < 0.05 considered significant. All values are given as means ± SEM for n experiments.

Results

Hypoxia Down-Regulates PP1γ Expression.

Previous studies determined that hypoxia represses CREB expression in epithelial cells (7) and that such repression activates transcription of select CRE-bearing gene products. To gain insight into potential pathways of CREB repression, differential mRNA display methods were used. RNA derived from epithelial cells exposed to hypoxia (0–16 h) were compared by arbitrary upstream/anchored downstream primer design and by quantitative gene array methods. This analysis revealed that the vast majority of genes remained unaltered in response to hypoxia (84% unaltered by arbitrary primer design and 96% unaltered by gene array). Of interest to our hypothesis that CREB repression is targeted to proteasomal degradation, both the arbitrary-primer and gene-array methods revealed significant down-regulation of PP1γ (27, 28), a serine/threonine phosphatase previously associated with the dephosphorylation of CREB (29). Thus, we hypothesized that PP1 depletion may account for the hypoxia-induced hyperphosphorylation of CREB and subsequent phosphorylation-dependent proteasomal degradation (15).

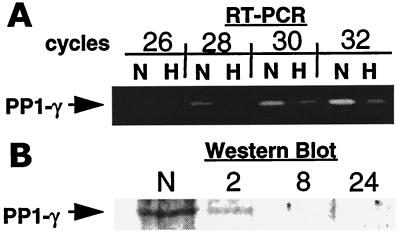

To confirm that hypoxia decreases PP1γ expression, we investigated PP1γ mRNA levels and protein expression by semiquantitative PCR and Western blotting, respectively. mRNA levels for PP1γ were decreased significantly in response to hypoxia (Fig. 1A). Furthermore, protein expression was decreased rapidly in a time-dependent manner (decreased expression by 2 h; Fig. 1B). These results confirm our initial observation that hypoxia elicits decreased expression of PP1γ.

Figure 1.

Hypoxia decreases expression of PP1γ. (A) Reverse transcription–PCR (RT-PCR) was used to confirm results obtained in differential mRNA display. PP1γ message was detected in T84 cells. Samples were obtained after 26, 28, 30, or 32 PCR cycles. PP1γ mRNA was diminished in hypoxic cells (H) when compared with normoxic controls (N). (B) Western blot analysis was performed to determine the impact of hypoxia on PP1γ expression in T84 cells. Data from A and B are representative of three experiments.

Sequence Homology in Phosphorylation-Targeted Degradation of Transcription Factors.

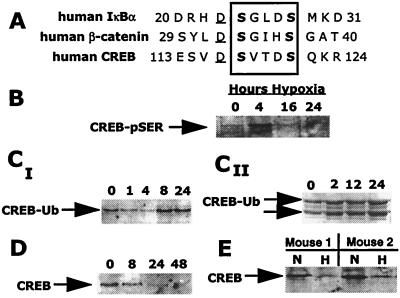

Previous work by others has identified an amino acid consensus within the primary structure of IκB and β-catenin critical for phosphorylation-dependent targeting to proteasomal degradation (DS*UXXS*, where D is aspartic acid, S* is phosphoserine, U is a hydrophobic amino acid, and X is any amino acid; Fig. 2A; refs. 14 and 15). A search for a homologous sequence within the primary structure of CREB identified a motif between residues D115 and S121 (DSVTDS), which provides a potential site for phosphorylation-dependent targeting of CREB to proteasomal degradation.

Figure 2.

In vitro and in vivo localization of phosphorylation-dependent proteasomal-targeting motif in CREB. (A) Homologous serine phosphorylation sites within IκB, β-catenin, and CREB may represent phosphorylation-dependent targeting sites to ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (15). (B–D) Sequential serine phosphorylation (CREB-pSER), ubiquitination (CREB-Ub), and expression of CREB. (B) Exposure of T84 cells to hypoxia results in the transient serine phosphorylation of CREB, maximal at 4 h. (CI) Time-dependent CREB ubiquitination with onset at 8 h. (CII) Multiple ubiquitinated CREB species. (D) CREB is diminished in epithelial cells with a significant decrease observed by 24 h. (E) CREB levels are decreased in mucosal scrapings (epithelial enriched) from mice exposed to hypoxia. Data shown are representative of at least three experiments.

Hypoxia Elicits Phosphorylation, Ubiquitination, and Subsequent Degradation of CREB.

We next investigated whether hypoxia elicited the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of CREB. Initially, CREB immunoprecipitates were analyzed by Western blotting and immunodetected with anti-phosphoserine. These studies revealed that CREB is rapidly and transiently phosphorylated (maximum 4 h) at one or more serine phosphorylation sites (Fig. 2B) in response to hypoxia. It is unlikely that such serine phosphorylation represents the PKA binding site (Ser133), because T84 cells engineered to express stably mutated CREB [retroviral-mediated gene transfer of a Ser-Ala mutation at the previously described PKA phosphorylation site (Ser133)] were phosphorylated to an extent equivalent to that of cells overexpressing the wild-type protein (data not shown). These data suggest that ambient hypoxia establishes intracellular conditions for serine phosphorylation on CREB at sites independent of the PKA binding site.

We next investigated whether CREB is sequentially ubiquitinated. Epithelia were exposed to increasing periods of hypoxia and lysed, and CREB immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS/PAGE, Western blotted, and immunoprobed for ubiquitin. As shown in Fig. 2C, hypoxia elicited the ubiquitination of CREB in a time-dependent manner and occurred temporally downstream of CREB phosphorylation (maximum by 8 h). Important in this regard, basal CREB ubiquitination was observed consistently in control cells (i.e., normoxic exposure; Fig. 2C), suggesting that this motif may function in the native turnover of CREB.

Subsequently, we investigated the impact of hypoxia on total CREB expression. Consistent with previous work (7), CREB expression was repressed in a hypoxia-time-dependent manner (Fig. 2D). Decreased CREB expression was detectable by 8 h and nearly complete by 24 h. Furthermore, in colonic mucosal scrapings from mice exposed to hypoxic conditions for 8 h, CREB levels were reduced dramatically (Fig. 2E).

In contrast to the above data, the CREB-like transcription factor ATF2 does not bear a homologous proteasomal targeting motif, and ATF2 expression was stable during similar periods of hypoxia (data not shown). Importantly, studies have indicated that ATF2 is ubiquitinated before proteasomal degradation (10, 11). These data suggest that the targeting mechanism for ATF2 to ubiquitination is clearly different from that of CREB. Taken together, these results indicate a degree of specificity for this proteasomal targeting motif and the presence of a specific phosphorylation-dependent targeting sequence within the primary structure of a number of transcription factors. Thus, hypoxia elicits the phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of CREB in a temporally sequential manner.

Phosphopeptides Corresponding to CREB Proteasomal Targeting Sequence Inhibit CREB Ubiquitination.

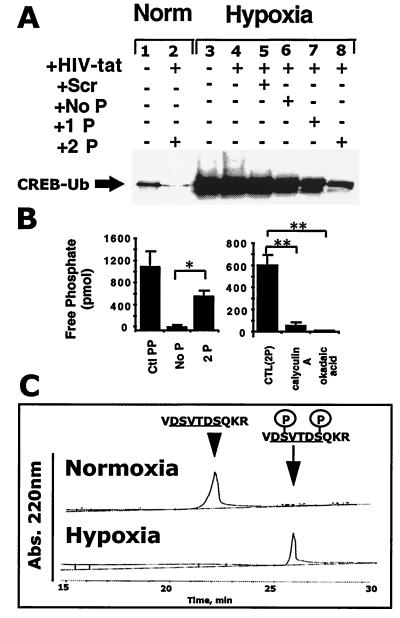

To investigate a direct role for proteasomal targeting motifs in CREB ubiquitination during hypoxia, epithelial cells were loaded with peptides corresponding to the CREB targeting sequence. As shown in Fig. 3A, HIV-tat peptide-facilitated loading of intact epithelia with differentially phosphorylated peptides resulted in significant decreases in hypoxia-elicited CREB ubiquitination. Although the scrambled peptide resulted in no ubiquitination inhibition (99.3 ± 9.8% of hypoxic control by densitometry), the unphosphorylated (73.4 ± 1.9%), the single-phosphorylated (47.0 ± 21.3%), and particularly the double phosphorylated peptide (19.7 ± 14.0%) strongly inhibited CREB ubiquitination (Fig. 3A). HIV-tat peptide, alone or in combination with scrambled peptide, did not influence ubiquitination significantly, suggesting a high degree of specificity for the proteasomal targeting motif. These data indicate a direct role for the targeting of CREB to proteasomal degradation through hypoxia-elicited phosphorylation of a specific sequence between residues D115 and S121.

Figure 3.

Synthetic CREB targeting phosphopeptide sequences inhibit CREB ubiquitination in a phosphorylation-dependent manner. (A) Baseline level of CREB ubiquitination is detectable in T84 cells (Lane 1). Lane 2 represents normoxic CREB in the presence of the double-phosphorylated CREB-targeting phosphopeptide. Lane 3 represents hypoxic CREB in the absence of peptide treatment, and lanes 4–8 (left to right) represent CREB from hypoxia-treated cells in the presence of the HIV-tat peptide alone, HIV-tat with scrambled peptide, HIV-tat with the unphosphorylated CREB-targeting peptide, HIV-tat with the single-phosphorylated CREB-targeting peptide, and HIV-tat with the double-phosphorylated CREB-targeting peptide, respectively. Data are representative of two experiments. (B) The CREB targeting sequence is a substrate for PP1 dephosphorylation. (Left) Coincubation of the phosphorylated form of the CREB-targeting sequence (2P) with purified PP1 results in the liberation of free phosphate when compared with the unphosphorylated control (Ctl; No P; n = 6, P < 0.05). A threonine phosphopeptide (Ctl PP) served as a positive control. (Right) The phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid (4 μM) and calyculin A (400 nM) abolished PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of the phosphorylated targeting sequence of CREB (n = 6, P < 0.05). (C) Hypoxia decreases phosphopeptide dephosphorylation. Coincubation of the double-phosphorylated CREB-targeting sequence (2P) with normoxic T84 (Upper) but not hypoxic (Lower) lysates results in peptide dephosphorylation as measured by HPLC (representative tracings of two experiments). Abs., absorbance.

The CREB Targeting Sequence Is a Substrate for PP1.

We next determined whether the targeting sequence within CREB is a direct substrate for PP1 activity. To make this determination, phosphopeptides corresponding to the proposed target sequence of CREB were incubated with purified PP1 and examined for the liberation of free phosphate as a readout of phosphatase activity. As shown in Fig. 3B, the phosphorylated, but not the unphosphorylated, form of the target sequence resulted in a significant increase in free phosphate liberation (P < 0.025 by Student's t test). Specificity was determined through the use of the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid (4 μM) or calyculin A (400 nM; Fig. 3B) and revealed that both calyculin A (P < 0.01 by Student's t test) and okadaic acid (P < 0.01) significantly inhibited PP1-mediated dephosphorylation of the double-phosphorylated peptide. As additional evidence, we examined the direct dephosphorylation of synthetic phosphopeptides by whole-cell lysates derived from normoxic or hypoxic T84 cells. As shown in Fig. 3C, HPLC analysis revealed a near complete loss of dephosphorylating activity in hypoxic lysates (mean 4.9% conversion in 5 min, n = 2) compared with normoxic lysates (mean 68.6% conversion in 5 min, n = 2). As a control for these experiments, addition of okadaic acid (1 μM) during incubation of phosphopeptide with normoxic lysate resulted in a 91.8% inhibition of dephosphorylation (data not shown). These data indicate that proteasomal targeting motifs in CREB serve as substrates for PP1.

Biological Function Attributed to Proteasomal Targeting of CREB.

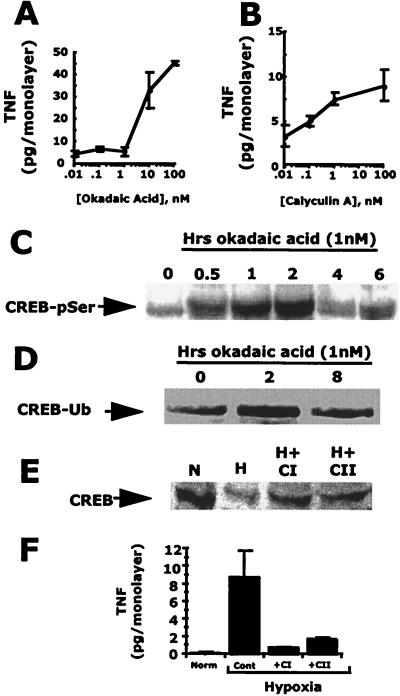

We next determined whether decreased PP1γ activity and targeted proteasomal activity correlate with a CREB-dependent biological activity. The pharmacological inhibitors okadaic acid and calyculin A were used to block protein phosphatase activity in normoxic cells, and predictive readouts of hypoxia were assessed. In this case, polarized release of TNFα was used as a readout. We have previously demonstrated that CREB functions as a repressor for TNFα gene expression and, further, that the loss of CREB during hypoxia results in functional TNFα protein expression (6, 7). As shown in Fig. 4, in a concentration-dependent manner, both okadaic acid (Fig. 4A, P < 0.05) and calyculin A (Fig. 4B, P < 0.05) induced TNFα release in normoxic epithelial monolayers. Furthermore, treatment of cells with okadaic acid alone resulted in serine phosphorylation (Fig. 4C) and ubiquitination (Fig. 4D) of CREB. Pharmacological inhibition of proteasome function with the peptide aldehydes ALLM [100 μM] and ALLN [100 μM] (22), respectively, resulted in diminished CREB degradation in hypoxia and decreased TNFα release. As shown in Fig. 4E, CREB degradation by hypoxia (59.1 ± 0.15% normoxic control) was inhibited by both ALLM and ALLN (112.8 ± 37.6 and 89.2 ± 13.1% of normoxic controls, respectively; Fig. 4E), and the induction of epithelial TNFα was similarly blocked (Fig. 4F; P < 0.05; n = 3 in each case). The more specific proteasome inhibitor lactacystin also inhibited hypoxia-elicited TNFα release by 41 ± 2% (P < 0.05; n = 5; data not shown). Such results support a role for both PP1γ and proteasomes in biological activity mediated by hypoxia.

Figure 4.

Pharmacological inhibition of protein phosphatase induces the hypoxic phenotype. Treatment of T84 cells grown on permeable support inserts with okadaic acid (A) or calyculin A (B) results in the concentration-dependent induction of TNFα. Treatment of T84 cells with okadaic acid (1 nM) resulted in a time-dependent serine phosphorylation (CREB-pSer) (C) and ubiquitination (CREB-Ub) (D) of CREB. (D) T84 cells exposed to hypoxia have decreased levels of nuclear CREB (lane 2) when compared with normoxic controls (lane 1). In the presence of ALLN or ALLM (100 μM each), hypoxia-elicited CREB depletion is decreased. (E) Hypoxia elicits release of TNFα. In the presence of ALLN or ALLM, hypoxia-elicited TNFα release is inhibited significantly (n = 3–6; P < 0.05 in each case). T84 cells exposed to hypoxia have decreased levels of nuclear CREB (lane 2) when compared with normoxic controls (lane 1). In the presence of ALLN (CI) or ALLM (CII; 100 μM each), hypoxia-elicited CREB depletion is decreased. (F) ALLN or ALLM inhibit hypoxia-elicited TNFα release (n = 3–6; P < 0.05 in each case).

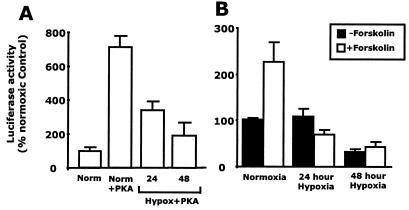

Impact of Hypoxia on CREB-Dependent Transcriptional Activity.

As additional evidence, we investigated the impact of hypoxia CREB-dependent transcriptional activity. Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells were transfected with a CREB-dependent luciferase reporter, with or without cotransfection with a PKA plasmid, and exposed to hypoxia. Luciferase activity in cotransfected cells was increased significantly (715 ± 60% of control; P < 0.001) when compared with that in cells transfected with the reporter plasmid alone. This PKA-activated luciferase expression was diminished by hypoxia in a time-dependent manner at 24 and 48 h (346 ± 45% and 197 ± 70% of cells transfected with the reporter plasmid alone, respectively; P < 0.005; Fig. 5A). Furthermore, luciferase activity was increased (227 ± 40% of control) in normoxic cells transfected with the reporter plasmid and cAMP agonist forskolin (2 μM). Hypoxia inhibited this forskolin response in a time-dependent manner at 24 h and further at 48 h (70 ± 8% and 43 ± 10% of control, respectively; Fig. 5B). Such data provide additional evidence for a functional loss of CREB in hypoxia.

Figure 5.

Hypoxia inhibits CREB-dependent gene transcription. (A) T84 cells were cotransfected with a CRE-luciferase reporter gene and cAMP-dependent PKA. Normoxic cotransfectants (Norm + PKA) demonstrated increased luciferase activity when compared with cells transfected with the luciferase reporter gene alone (Norm). Cells exposed to hypoxia for 24 and 48 h showed a time-dependent decrease in luciferase activity. (B) T84 cells were transfected with a CRE-luciferase reporter gene and exposed to hypoxia (0–48 h). Cells were then exposed to forskolin (2 μM). In normoxic cells, forskolin stimulated a significant increase in luciferase gene expression. Data shown are representative of three experiments.

Discussion

Significant evidence supports a role for cellular hypoxia in the maintenance of inflammation in a number of disease states (1). In previous work, we demonstrated that hypoxia elicits the expression of a specific subset of genes in epithelia. This set of genes was restricted primarily to those involved in proinflammatory events (6, 7). Because the presence of a CREB-binding motif seems to be necessary for transcriptional induction of proinflammatory genes by hypoxia, we explored mechanisms of CREB degradation and transcriptional activation.

The ubiquitin/proteasome pathway represents a mechanism by which targeted proteins, including transcription factors, specifically signal through degradative pathways (30). Initial insight into potential mechanisms of CREB degradation were gained by our previous studies indicating that hypoxia elicits coincidental NF-κB activation in epithelia (7). The role of NF-κB in hypoxia-elicited responses in vivo remains unclear. Other groups have implicated tyrosine phosphorylation of IκB (31) or oxygen radicals (32, 33) in mediating NF-κB activation. Similarly, other transcription factors known to associate with CREB in transcriptional complexes have been demonstrated to be degraded by the proteasome. These transcription factors include hypoxia-inducible factor 1α (12, 13) and ATF2 (10, 11), and, importantly, CREB may cooperate as an activation signal for these complexes during hypoxia, such as occurs with the lactate dehydrogenase-A gene (34). Recent work has revealed that at least one level of specificity includes phosphorylation-dependent targeting to the proteasome pathway and identified an amino acid-consensus motif that, when phosphorylated, served as a substrate for ubiquitination (14–16). On closer examination of the primary structure of CREB, it was revealed that a homologous sequence existed (amino acid residues 115 and 121, DSVTDS). This consensus does not exist within the CREB-related ATF2 transcription factor or the hypoxia-inducible factor 1α structure (unpublished observation), which are presumably targeted to ubiquitination via a different signaling mechanism. Because CREB expresses such a targeting sequence and is degraded during exposure to hypoxia, we hypothesized that this targeting sequence confers sensitivity to phosphorylation-dependent targeting to proteasomal degradation.

As proof of principle for this hypothesis, it was necessary to establish that these events (CREB phosphorylation, ubiquitination, degradation, and transcriptional activity) occur in a temporal fashion, that phosphopeptides corresponding to the CREB targeting motif block ubiquitination, and that we could reproduce such findings by using a pharmacological approach. Our studies initially focused on determining potential targets responsible for hypoxia-elicited CREB hyperphosphorylation and degradation. Included among the genes differentially expressed in hypoxia was PP1γ, an enzyme involved in a range of serine/threonine dephosphorylation reactions (31). Important in this regard, work by Alberts et al. (29) demonstrated that PP1 was the protein phosphatase involved in the regulation of CREB dephosphorylation and subsequent control of transcriptional activity. Subsequent studies revealed that hypoxia elicited a time-dependent depletion of CREB expression and that phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and subsequent degradation of CREB occur, respectively, in a manner that is temporally consistent with sequential events. Work by Beitner-Johnson and Millhorn (35) has demonstrated that brief periods of mild hypoxia elicit the phosphorylation of CREB at the PKA phosphorylation site Ser133 (within the RRPSY consensus), resulting in induction of transcriptional events. These authors did not, however, examine CREB levels at later time points of hypoxia, making comparison of results difficult. Nonetheless, in our studies, hypoxia-elicited phosphorylation of CREB does not seem to be restricted to this site, because stable cell lines expressing CREB mutated at Ser133 (Ser-Ala mutation) did not display decreased serine phosphorylation when compared with wild-type CREB cell lines.

To define the direct role of the phosphorylation-consensus motif, phosphopeptides corresponding to this targeting domain in CREB (DSVTDS) were loaded into intact cells before hypoxia. Difficulties in accessing the intracellular compartment with the peptides were overcome by coincubation of cells with peptides in the presence of HIV-tat peptide that, through an as yet unknown mechanism, facilitates efficient uptake of peptides into cells (36, 37). Phosphopeptides corresponding to the proposed target sequences inhibited hypoxia-elicited CREB ubiquitination in a manner dependent on the phosphorylation state of the peptide.

Additional evidence was provided by using the phosphatase inhibitors okadaic acid and calyculin A. Although not specific for PP1γ, these compounds nonetheless mimicked the hypoxia phenotype in control cells, and, importantly, the CREB ubiquitination peptides were demonstrated to serve as a direct substrate for PP1 (phosphatase assay). Furthermore, dephosphorylation of these phosphopeptides was reduced significantly in hypoxia, likely indicating that diminished specific CREB dephosphorylation in hypoxia. To demonstrate a direct impact of hypoxia on CREB-dependent gene transcription, a transient transfection approach was adopted. Hypoxia significantly diminished both basal and stimulated CREB-dependent transcriptional activity in cells transfected with a luciferase reporter gene under the control of CREB. Taken together, these data indicate that hypoxia establishes intracellular conditions favorable for the stable phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of CREB, an event that mediates alterations in basal transcriptional activity.

It is only recently that substrate-targeted degradation processes have been studied, and significant questions remain unanswered regarding the specificity of this process. For example, what enzyme complexes recognize phosphorylated CREB, and to what degree are they specific? Previous studies with phosphorylated IκB suggested that the E3 family of ubiquitin-substrate ligase family of enzymes likely mediate IκB degradation; however, it was also suggested that E3 is unlikely to target single substrates (38). Rather, it was suggested that individual ligases may recognize similar, but not identical, substrates and thus may provide both specificity and flexibility in this particular reaction. Recent work, in fact, identified an Fbox/WD (Trp-Asp) domain protein belonging to a recently distinguished family of beta-TrCP/Slimb proteins, called E3RS (IκB), that may specifically target IκB ubiquitination and degradation (14). Whether similar enzymes or enzyme complexes provide equivalent specificity for CREB remains to be seen.

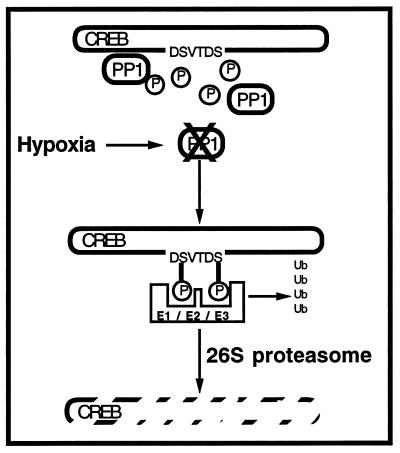

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that hypoxia-elicited targeting of transcription factors may account for a mechanism by which specific targeting to the proteasome-degradation pathway mediates the induction of the hypoxic phenotype (Fig. 6). Furthermore, these data identify a specific degradative targeting mechanism for proteins under conditions of hypoxia.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of phosphorylation-dependent targeting of CREB to proteasomal degradation by hypoxia. Hypoxia elicits the rapid depletion of PP1, resulting in decreased dephosphorylation of proteins within the targeting sequence. Resultant hyperphosphorylation of proteins attracts ubiquitination (Ub) through the coordinated activities of E1, E2, and E3. Ubiquitination of targeted peptides leads to degradation via the 26S proteasome. Proteins degraded through this targeting system in hypoxia include transcriptional modulators important in transformation to the hypoxic phenotype.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge assistance from Robyn Carey. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK50189, DE13499, and HL60569 to S.P.C., DK02682 to C.T.T., and DK02564 to G.T.F., and by the Crohn's and Colitis Foundation of America.

Abbreviations

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- PP1

protein phosphatase 1

- ATF2

activating transcription factor 2

- PKA

cAMP-dependent protein kinase

- CRE

cAMP response element

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Article published online before print: Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 10.1073/pnas.220211797.

Article and publication date are at www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.220211797

References

- 1.Taylor C T, Colgan S P. Pharm Res. 1999;16:1498–1505. doi: 10.1023/a:1011936016833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunn HF, Poyton RO. Physiol Rev. 1996;6:839–885. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.3.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Semenza G L. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1998;8:588–594. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(98)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang G L, Jiang B H, Rue E A, Semenza G L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5510–5514. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.12.5510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang G L, Semenza G L. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:1230–1237. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.3.1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taylor C T, Dzus A L, Colgan S P. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:657–668. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70579-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taylor C T, Fueki N, Agah A, Hershberg R M, Colgan S P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19447–19454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.27.19447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bochtler M, Ditzl L, Groll M, Hartman C, Huber R. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1999;28:295–317. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeMartino G N, Slaughter C A. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:22123–22126. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.32.22123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Firestein R, Feuerstein N. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:5892–5902. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fuchs S Y, Ronai Z. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:3289–3298. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.5.3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang L E, Gu J, Schau M, Bunn H F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7987–7992. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.14.7987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sutter C H, Laughner E, Semenza G L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4748–4753. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080072497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yaron A, Hatzubai A, Davis M, Lavon I, Amit S, Manning A M, Andersen J S, Mann M, Mercurio F, Yinon B N. Nature (London) 1998;396:590–594. doi: 10.1038/25159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laney JD, Hochstrasser M. Cell. 1999;97:427–430. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80752-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aberle H, Bauer A, Stappert J, Kispert A, Kemler R. EMBO J. 1997;16:3797–3804. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.13.3797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Craig K L, Tyers M. Prog Biophys Mol Biol. 1999;72:299–328. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(99)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deshaies R J. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:435–467. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dharmsathaphorn K, Madara J L. Methods Enzymol. 1990;192:354–389. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)92082-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dharmsathaphorn K, McRoberts J, Mandel K G, Tisdale L D, Masui H. Am J Physiol. 1984;246:G204–G208. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1984.246.2.G204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lockhart D J, Dong H, Byrne M C, Follettie M T, Gallo M V, Chee M S, Mittmann M, Wang C, Kobayashi M, Horton H, et al. Nat Biotechnol. 1996;14:1675–1680. doi: 10.1038/nbt1296-1675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zünd G, Uezono S, Stahl G L, Dzus A L, McGowan F X, Hickey P R, Colgan S P. Am J Physiol. 1997;273:C1571–C1580. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fawell S, Seery J, Daikh Y, Moore C, Chen L L, Pepinsky B, Barsoum J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:664–668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vives E, Brodin P, Lebleu B. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16010–16017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Colgan S P, Dzus A L, Parkos C A. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1003–1015. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.3.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hershberg R M, Framson P E, Cho D H, Lee L Y, Kovats S, Beitz J, Blum J S, Nepom G T. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:204–215. doi: 10.1172/JCI119514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Norman S A, Mott D M. Mamm Genome. 1994;5:41–45. doi: 10.1007/BF00360567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barker H M, Craig S P, Spurr N K, Cohen P T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1178:228–233. doi: 10.1016/0167-4889(93)90014-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alberts A S, Montminy M, Shenolikar S, Feramisco J R. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:4398–4407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.7.4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tansey P. Mol Med. 1999;5:773–782. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koong A C, Chen E Y, Giaccia A J. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1425–1430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ho E, Chen G, Bray T M. FASEB J. 1999;13:1845–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Das D K, Maulik N, Sato M, Ray P S. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999;196:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Firth J D, Ebert B L, Ratcliffe P J. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:21021–21027. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.36.21021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Beitner-Johnson D, Millhorn D E. J Biol Chem. 1999;273:19834–19839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.31.19834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hawiger J. Curr Opin Immunol. 1997;9:189–194. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(97)80134-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwarze S R, Ho A, Vocero-Akbani A, Dowdy S F. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaron A, Gonen H, Alkalay I, Hatzubai A, Jung S, Beyth S, Mercurio F, Manning A M, Ciechanover A, Ben-Neriah Y. EMBO J. 1997;16:6486–6494. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.21.6486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]