Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To assess whether long term trends over time in acute coronary heart disease (CHD) event rates have influenced the burden of prevalent CHD in British men. DESIGN—Longitudinal cohort study. PARTICIPANTS—7735 men, aged 40-59 at entry (1978-80), selected from 24 British towns. METHODS—The prevalences of current angina symptoms and history of diagnosed CHD were ascertained by questionnaire in 1978-80, 1983-85, 1992, and 1996. New major CHD events (fatal and non-fatal) were ascertained throughout the study from National Health Service central registers and general practice record reviews. Age adjusted trends in CHD prevalence were compared with trends in major CHD event rates. RESULTS—From 1978-1996 there was a clear decline in the prevalence of current angina symptoms: the age adjusted annual percentage change in odds was -1.8% (95% confidence interval (CI) -2.8% to -0.8%). However, there was no evidence of a trend in the prevalence of history of diagnosed CHD (annual change in odds 0.1%, 95% CI -1.0% to 1.2%). Over the same period, the CHD mortality rate fell substantially (annual change -4.1%, 95% CI -6.5% to -1.6%); rates of non-fatal myocardial infarction, all major CHD events, and first major CHD event fell by -1.7% (95% CI -3.9% to 0.5%), -2.5% (95% CI -4.1% to -0.8%), and -2.4% (95% CI% -4.3 to -0.4%), respectively. CONCLUSIONS—These results suggest that middle aged British men are less likely to experience symptoms of angina than in previous decades but are just as likely to have a history of diagnosed CHD. Despite falling rates of new major events and falling symptom prevalence, the need for secondary prevention among middle aged men with established CHD is as great as ever. Keywords: coronary heart disease; angina; prevalence; trends

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (134.0 KB).

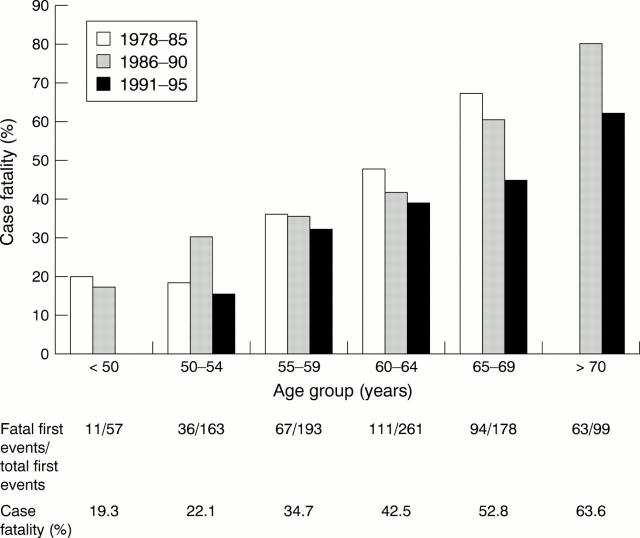

Figure 1 .

Prevalence of coronary heart disease (CHD) by age and questionnaire. (A) Current angina symptoms. (B) History of diagnosed CHD.

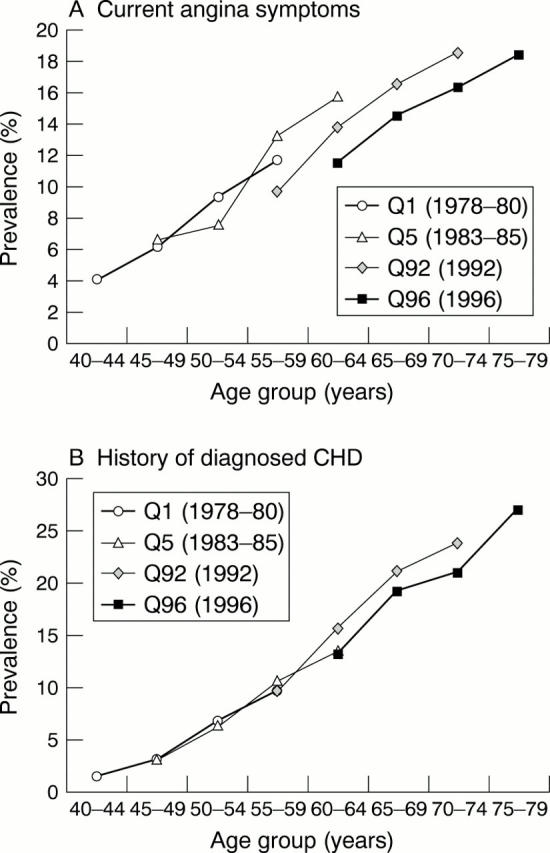

Figure 2 .

Case fatality (proportion of events fatal within 28 days) for first major CHD event by age at event and year of event.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Cook D. G., Shaper A. G., MacFarlane P. W. Using the WHO (Rose) angina questionnaire in cardiovascular epidemiology. Int J Epidemiol. 1989 Sep;18(3):607–613. doi: 10.1093/ije/18.3.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeStefano F., Merritt R. K., Anda R. F., Casper M. L., Eaker E. D. Trends in nonfatal coronary heart disease in the United States, 1980 through 1989. Arch Intern Med. 1993 Nov 8;153(21):2489–2494. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glader E. L., Stegmayr B. Declining prevalence of angina pectoris in middle-aged men and women. A population-based study within the Northern Sweden MONICA Project. Multinational Monitoring of Trends and Cardiovascular Disease. J Intern Med. 1999 Sep;246(3):285–291. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunink M. G., Goldman L., Tosteson A. N., Mittleman M. A., Goldman P. A., Williams L. W., Tsevat J., Weinstein M. C. The recent decline in mortality from coronary heart disease, 1980-1990. The effect of secular trends in risk factors and treatment. JAMA. 1997 Feb 19;277(7):535–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuulasmaa K., Tunstall-Pedoe H., Dobson A., Fortmann S., Sans S., Tolonen H., Evans A., Ferrario M., Tuomilehto J. Estimation of contribution of changes in classic risk factors to trends in coronary-event rates across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet. 2000 Feb 26;355(9205):675–687. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lampe F. C., Walker M., Lennon L. T., Whincup P. H., Ebrahim S. Validity of a self-reported history of doctor-diagnosed angina. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999 Jan;52(1):73–81. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00146-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osler M., Sørensen T. I., Sørensen S., Rostgaard K., Jensen G., Iversen L., Kristensen T. S., Madsen M. Trends in mortality, incidence and case fatality of ischaemic heart disease in Denmark, 1982-1992. Int J Epidemiol. 1996 Dec;25(6):1154–1161. doi: 10.1093/ije/25.6.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosamond W. D., Chambless L. E., Folsom A. R., Cooper L. S., Conwill D. E., Clegg L., Wang C. H., Heiss G. Trends in the incidence of myocardial infarction and in mortality due to coronary heart disease, 1987 to 1994. N Engl J Med. 1998 Sep 24;339(13):861–867. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199809243391301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose G., McCartney P., Reid D. D. Self-administration of a questionnaire on chest pain and intermittent claudication. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1977 Mar;31(1):42–48. doi: 10.1136/jech.31.1.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salomaa V., Miettinen H., Kuulasmaa K., Niemelä M., Ketonen M., Vuorenmaa T., Lehto S., Palomäki P., Mähönen M., Immonen-Räihä P. Decline of coronary heart disease mortality in Finland during 1983 to 1992: roles of incidence, recurrence, and case-fatality. The FINMONICA MI Register Study. Circulation. 1996 Dec 15;94(12):3130–3137. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.12.3130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sans S., Kesteloot H., Kromhout D. The burden of cardiovascular diseases mortality in Europe. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology on Cardiovascular Mortality and Morbidity Statistics in Europe. Eur Heart J. 1997 Aug;18(8):1231–1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Cook D. G., Walker M., Macfarlane P. W. Recall of diagnosis by men with ischaemic heart disease. Br Heart J. 1984 Jun;51(6):606–611. doi: 10.1136/hrt.51.6.606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaper A. G., Pocock S. J., Walker M., Cohen N. M., Wale C. J., Thomson A. G. British Regional Heart Study: cardiovascular risk factors in middle-aged men in 24 towns. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1981 Jul 18;283(6285):179–186. doi: 10.1136/bmj.283.6285.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigfusson N., Sigvaldason H., Steingrimsdottir L., Gudmundsdottir I. I., Stefansdottir I., Thorsteinsson T., Sigurdsson G. Decline in ischaemic heart disease in Iceland and change in risk factor levels. BMJ. 1991 Jun 8;302(6789):1371–1375. doi: 10.1136/bmj.302.6789.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigurdsson E., Thorgeirsson G., Sigvaldason H., Sigfusson N. Prevalence of coronary heart disease in Icelandic men 1968-1986. The Reykjavik Study. Eur Heart J. 1993 May;14(5):584–591. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/14.5.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sytkowski P. A., D'Agostino R. B., Belanger A., Kannel W. B. Sex and time trends in cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality: the Framingham Heart Study, 1950-1989. Am J Epidemiol. 1996 Feb 15;143(4):338–350. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall-Pedoe H., Kuulasmaa K., Mähönen M., Tolonen H., Ruokokoski E., Amouyel P. Contribution of trends in survival and coronary-event rates to changes in coronary heart disease mortality: 10-year results from 37 WHO MONICA project populations. Monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 1999 May 8;353(9164):1547–1557. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)04021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tunstall-Pedoe H., Vanuzzo D., Hobbs M., Mähönen M., Cepaitis Z., Kuulasmaa K., Keil U. Estimation of contribution of changes in coronary care to improving survival, event rates, and coronary heart disease mortality across the WHO MONICA Project populations. Lancet. 2000 Feb 26;355(9205):688–700. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)11181-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volmink J. A., Newton J. N., Hicks N. R., Sleight P., Fowler G. H., Neil H. A. Coronary event and case fatality rates in an English population: results of the Oxford myocardial infarction incidence study. The Oxford Myocardial Infarction Incidence Study Group. Heart. 1998 Jul;80(1):40–44. doi: 10.1136/hrt.80.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M., Shaper A. G., Cook D. G. Non-participation and mortality in a prospective study of cardiovascular disease. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987 Dec;41(4):295–299. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.4.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M., Shaper A. G., Lennon L., Whincup P. H. Twenty year follow-up of a cohort based in general practices in 24 British towns. J Public Health Med. 2000 Dec;22(4):479–485. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/22.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeiner-Henriksen T. Comparison of personal interview and postal inquiry methods for assessing prevalence of angina and possible infarction. J Chronic Dis. 1972 Aug;25(8):433–440. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(72)90206-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]