Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (193.3 KB).

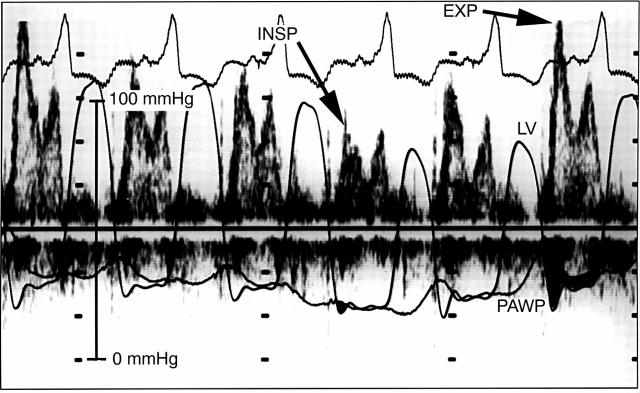

Figure 1 .

Transmitral flow velocity in a patient with constrictive pericarditis. During peak inspiration (INSP), there is a decrease in the early diastolic driving pressure across the mitral valve, seen as the initial gradient between the pressure in the left ventricle (LV) and the pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP). This results in a decrease in the initial E velocity on the transmitral flow velocity curve. During expiration (EXP), there is an increase in the transmitral gradient between the pressure in the LV and the PAWP, resulting in an increase in the initial E velocity and the transmitral flow velocity curve. Data were obtained simultaneously by Doppler echocardiography and high fidelity manometer tipped catheters.

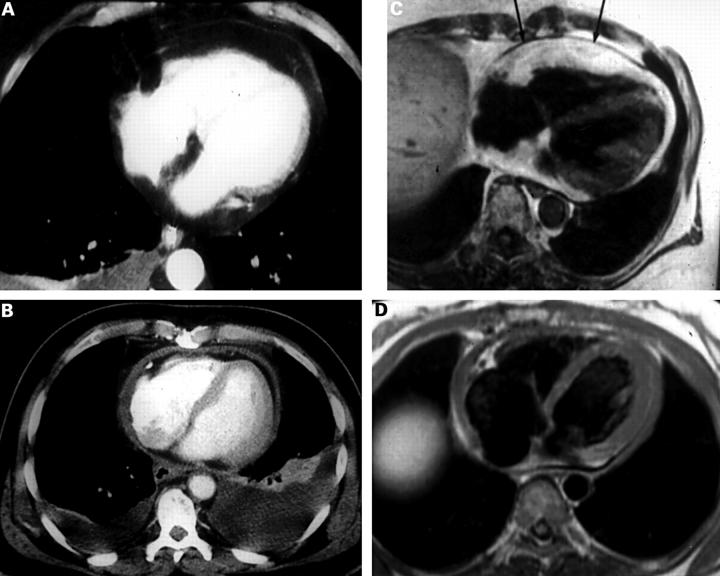

Figure 2 .

Normal and abnormal pericardium seen on computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies. (A) CT scan of normal pericardium. (B) CT scan of thickened pericardium. (C) MRI scan of normal thick pericardium (arrows). (D) MRI scan of a thickened pericardium. Reproduced from Breen18 with permission of Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

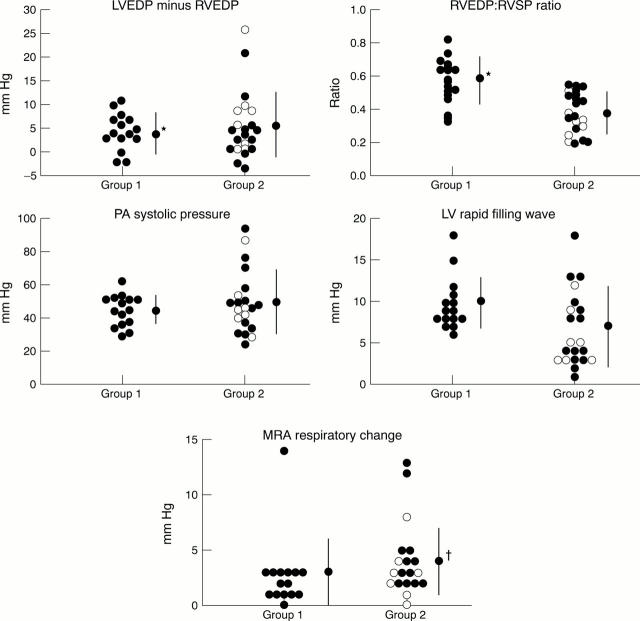

Figure 3 .

Conventional criteria at cardiac catheterisation. Group 1, patients with constrictive pericarditis; group 2, patients with restrictive cardiomyopathy or other types of cardiomyopathy and a normal pericardium. Although there are significant differences between the two groups, overlap makes it difficult to apply the criteria in an individual case. LVEDP, left ventricular end diastolic pressure; RVEDP, right ventricular end diastolic pressure; RVSP, right ventricular systolic pressure; PA, pulmonary artery; LV, left ventricular; MRA, mean right atrial pressure. Reproduced from Hurrell et al 7 with permission of the American Heart Association.

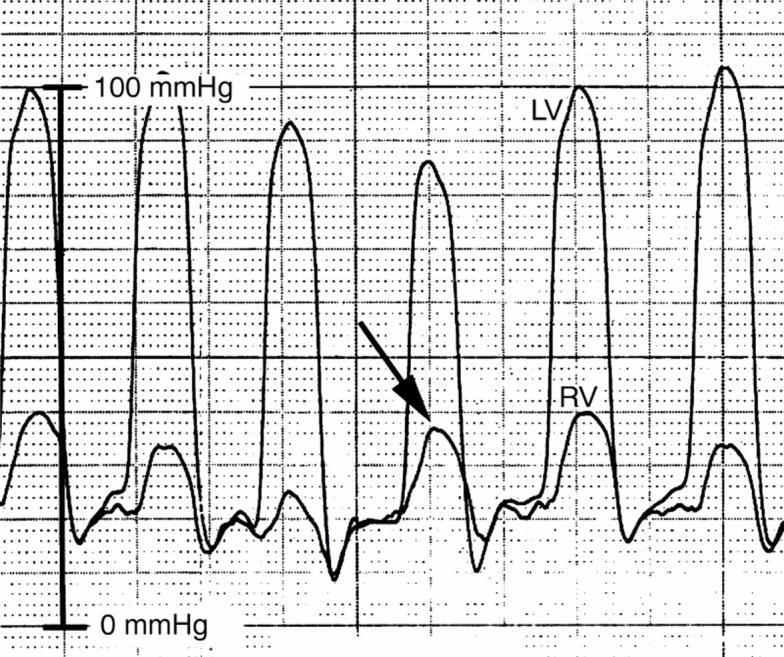

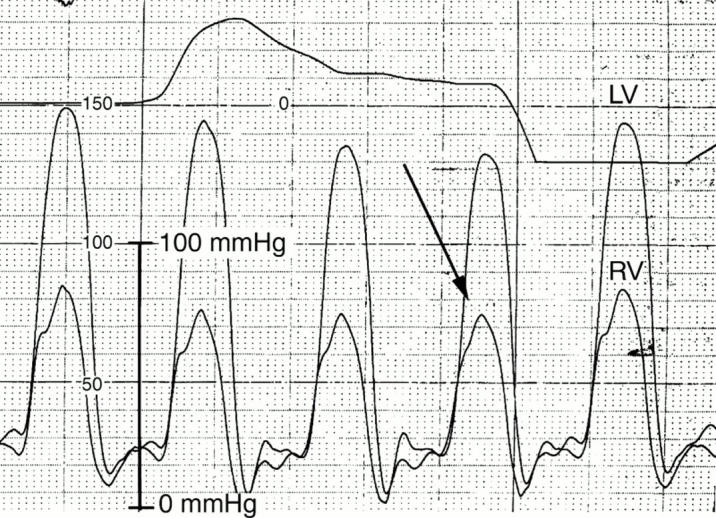

Figure 4 .

Pressures in the left (LV) and right ventricle (RV) of a patient with constrictive pericarditis. During peak inspiration (arrow), there is a decrease in LV pressure and a concomitant increase in RV pressure, indicating discordance of ventricular pressures.

Figure 5 .

Pressures in the left (LV) and right ventricle (RV) of a patient with restrictive cardiomyopathy. During peak inspiration (arrow) there is a decrease in LV pressure and a concomitant decrease in RV pressure, indicating concordance of ventricular pressures.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ammash N. M., Seward J. B., Bailey K. R., Edwards W. D., Tajik A. J. Clinical profile and outcome of idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2000 May 30;101(21):2490–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.21.2490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breen J. F. Imaging of the pericardium. J Thorac Imaging. 2001 Jan;16(1):47–54. doi: 10.1097/00005382-200101000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONNOLLY D. C., WOOD E. H. Cardiac catheterization in heart failure and cardiac constriction. Trans Am Coll Cardiol. 1957 Jan;7:191–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler N. O. Constrictive pericarditis: its history and current status. Clin Cardiol. 1995 Jun;18(6):341–350. doi: 10.1002/clc.4960180610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank H., Globits S. Magnetic resonance imaging evaluation of myocardial and pericardial disease. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1999 Nov;10(5):617–626. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1522-2586(199911)10:5<617::aid-jmri5>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatle L. K., Appleton C. P., Popp R. L. Differentiation of constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy by Doppler echocardiography. Circulation. 1989 Feb;79(2):357–370. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.79.2.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Himelman R. B., Lee E., Schiller N. B. Septal bounce, vena cava plethora, and pericardial adhesion: informative two-dimensional echocardiographic signs in the diagnosis of pericardial constriction. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1988 Sep-Oct;1(5):333–340. doi: 10.1016/s0894-7317(88)80007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell D. G., Nishimura R. A., Higano S. T., Appleton C. P., Danielson G. K., Holmes D. R., Jr, Tajik A. J. Value of dynamic respiratory changes in left and right ventricular pressures for the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis. Circulation. 1996 Jun 1;93(11):2007–2013. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.93.11.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L. H., Oh J. K., Schaff H. V., Danielson G. K., Mahoney D. W., Seward J. B., Tajik A. J. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1999 Sep 28;100(13):1380–1386. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.13.1380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling L. H., Oh J. K., Tei C., Click R. L., Breen J. F., Seward J. B., Tajik A. J. Pericardial thickness measured with transesophageal echocardiography: feasibility and potential clinical usefulness. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 May;29(6):1317–1323. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)82756-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masui T., Finck S., Higgins C. B. Constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992 Feb;182(2):369–373. doi: 10.1148/radiology.182.2.1732952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney E., Shabetai R., Bhargava V., Shearer M., Weidner C., Mangiardi L. M., Smalling R., Peterson K. Cardiac amyloidosis, contrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 1976 Nov 4;38(5):547–556. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(76)80001-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimura R. A., Tajik A. J. Evaluation of diastolic filling of left ventricle in health and disease: Doppler echocardiography is the clinician's Rosetta Stone. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1997 Jul;30(1):8–18. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(97)00144-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. K., Hatle L. K., Seward J. B., Danielson G. K., Schaff H. V., Reeder G. S., Tajik A. J. Diagnostic role of Doppler echocardiography in constrictive pericarditis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Jan;23(1):154–162. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh J. K., Tajik A. J., Appleton C. P., Hatle L. K., Nishimura R. A., Seward J. B. Preload reduction to unmask the characteristic Doppler features of constrictive pericarditis. A new observation. Circulation. 1997 Feb 18;95(4):796–799. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.95.4.796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabetai R. Controversial issues in restrictive cardiomyopathy. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68 (Suppl 1):S47–S51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shabetai R., Fowler N. O., Guntheroth W. G. The hemodynamics of cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1970 Nov;26(5):480–489. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(70)90706-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel R. J., Shah P. K., Fishbein M. C. Idiopathic restrictive cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 1984 Aug;70(2):165–169. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.70.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaitkus P. T., Kussmaul W. G. Constrictive pericarditis versus restrictive cardiomyopathy: a reappraisal and update of diagnostic criteria. Am Heart J. 1991 Nov;122(5):1431–1441. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(91)90587-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOOD P. Chronic constrictive pericarditis. Am J Cardiol. 1961 Jan;7:48–61. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(61)90422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]