Abstract

Aims—There is a considerable discrepancy between data from the detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in atherosclerotic lesions obtained by means of immunocytochemistry and data obtained using the polymerase chain reaction. This study evaluated methods for the in situ detection and assessment of the viability of C pneumoniae bacteria.

Methods—Chlamydia pneumoniae membrane protein, heat shock protein 60, and lipopolysaccharide were detected by immunocytochemistry, and genomic DNA and 16S rRNA by in situ hybridisation in paraffin wax embedded sections of cultured HEp2 cells infected with C pneumoniae and of lungs from mice infected intranasally with C pneumoniae.

Results—Inclusions reactive for all three antigens, DNA, and 16S rRNA were seen in infected HEp2 cells, in all positive bronchus and alveolar epithelial cells, and in some of the positive infiltrate cells in the lungs of mice up to seven days after infection. In all alveolar macrophages and in the infiltrate cells positive for antigens only, the staining pattern was granularly dispersed throughout the cytoplasm up to seven days after infection. At 21 days after infection, only this granular staining pattern was seen for antigens in infiltrate cells and macrophages in the alveoli and bronchus associated lymphoid tissue. At this time point, DNA or 16S rRNA were detected sporadically, but always as inclusion-like staining.

Conclusions—Because antigens with an inclusion-like staining were detected only together with DNA and 16S rRNA, this type of staining pattern suggested the presence of viable bacteria. Thus, the granular staining pattern of antigens in the absence of staining for DNA and 16S is most likely caused by non-viable bacteria. In conclusion, these methods are suitable for the in situ detection of C pneumoniae and the assessment of its viability.

Key Words: Chlamydia pneumoniae • immunocytochemistry • in situ hybridisation • animal model

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (245.8 KB).

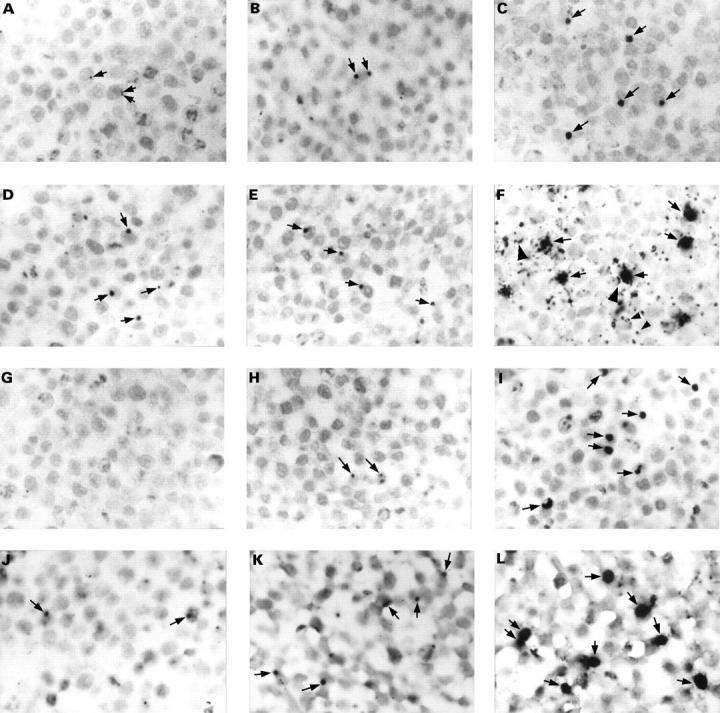

Figure 1 The detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in paraffin wax embedded sections of formalin fixed HEp2 cells infected with a multiplicity of infection of 0.1 inclusion forming units of C pneumoniae. Cells were fixed at 21 (A, D, G, and J), 29 (B, E, H, and K), and 46 (C, F, I, and L) hours after infection. Sections were immunostained for C pneumoniae membrane protein (A–C), LPS (D–F; with monoclonal antibody 16.3B6), or hsp60 (G–I), or hybridised for 16S rRNA (J–L). In the early stages of the developmental cycle of C pneumoniae, up to 29 hours post infection, only very small inclusions were seen (A, B, D, E, H, J, and K; arrows). No immunostaining was observed for hsp60 at 21 hours after infection (G). Inclusions were up to 10 times larger at a later stage of the developmental cycle (C, F, I, and L; arrows). Membranes of non-infected cells (F; large arrowheads) and vesicle-like structures (F; small arrowheads) were also immunostained for LPS. Counterstaining, nuclear fast red. Original magnification, x125 (A–L).

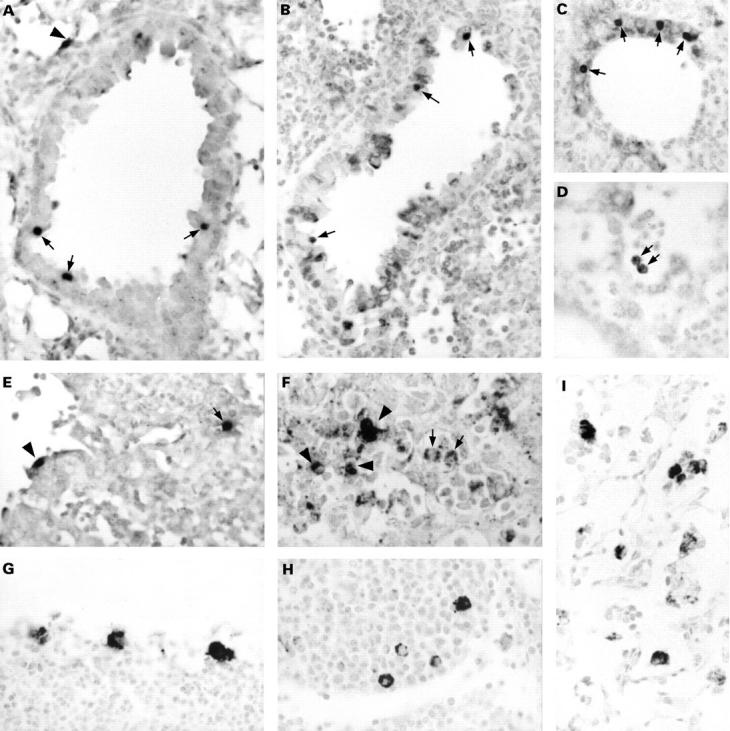

Figure 2 The detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae in paraffin wax embedded sections of formalin fixed lungs of mice intranasally infected with C pneumoniae. Results are from mice sacrificed at two (A–F) and 21 (G–I) days after infection. Sections were immunostained for membrane protein (G), lipopolysaccharide (B, F, and I; with monoclonal antibody 16.3B6), or hsp60 (C, D, and H), or hybridised for DNA (A) or 16S rRNA (E). In the early stages of infection, clearly recognisable inclusions were observed in bronchus epithelial cells (A–C; arrows) and in alveolar epithelial cells (A and E; arrowhead). Alveolar macrophages showed a vacuolised immunostaining pattern (D and F; arrows). Infiltrate cells were positive by immunostaining (F; arrowheads) and by in situ hybridisation (E; arrow). In the later stages of infection, macrophages in bronchus associated lymphoid tissue (G and H) and alveolar macrophages (I) showed a granular immunostaining pattern dispersed throughout their cytoplasm. Counterstaining, nuclear fast red. Original magnification, x125 (A–I).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alakärppä H., Surcel H. M., Laitinen K., Juvonen T., Saikku P., Laurila A. Detection of Chlamydia pneumoniae by colorimetric in situ hybridization. APMIS. 1999 Apr;107(4):451–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beatty W. L., Byrne G. I., Morrison R. P. Morphologic and antigenic characterization of interferon gamma-mediated persistent Chlamydia trachomatis infection in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993 May 1;90(9):3998–4002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.3998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutler A. M., Schumacher H. R., Jr, Whittum-Hudson J. A., Salameh W. A., Hudson A. P. Case report: in situ hybridization for detection of inapparent infection with Chlamydia trachomatis in synovial tissue of a patient with Reiter's syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 1995 Nov;310(5):206–213. doi: 10.1097/00000441-199511000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell S., Richmond S. J., Yates P. S., Storey C. C. Lipopolysaccharide in cells infected by Chlamydia trachomatis. Microbiology. 1994 Aug;140(Pt 8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1099/13500872-140-8-1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutilh B., Bébéar C., Taylor-Robinson D., Grimont P. A. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis by in situ hybridization with sulphonated total DNA. Ann Inst Pasteur Microbiol. 1988 Jan-Feb;139(1):115–127. doi: 10.1016/0769-2609(88)90099-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredricks D. N., Relman D. A. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch's postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996 Jan;9(1):18–33. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaydos C. A., Summersgill J. T., Sahney N. N., Ramirez J. A., Quinn T. C. Replication of Chlamydia pneumoniae in vitro in human macrophages, endothelial cells, and aortic artery smooth muscle cells. Infect Immun. 1996 May;64(5):1614–1620. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1614-1620.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grayston J. T., Kuo C. C., Coulson A. S., Campbell L. A., Lawrence R. D., Lee M. J., Strandness E. D., Wang S. P. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR) in atherosclerosis of the carotid artery. Circulation. 1995 Dec 15;92(12):3397–3400. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.12.3397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson L. A., Campbell L. A., Kuo C. C., Rodriguez D. I., Lee A., Grayston J. T. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from a carotid endarterectomy specimen. J Infect Dis. 1997 Jul;176(1):292–295. doi: 10.1086/517270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo C. C., Jackson L. A., Campbell L. A., Grayston J. T. Chlamydia pneumoniae (TWAR). Clin Microbiol Rev. 1995 Oct;8(4):451–461. doi: 10.1128/cmr.8.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meddens M. J., Quint W. G., van der Willigen H., Wagenvoort J. T., v Dijk W. C., Lindeman J., Herbrink P. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in culture and urogenital smears by in situ DNA hybridization using a biotinylated DNA probe. Mol Cell Probes. 1988 Dec;2(4):261–269. doi: 10.1016/0890-8508(88)90010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A., Vallinga C. E., Ossewaarde J. M. A microcarrier culture method for the production of large quantities of viable Chlamydia pneumoniae. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 1996 Sep;46(2):132–137. doi: 10.1007/s002530050794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer A., van Der Vliet J. A., Roholl P. J., Gielis-Proper S. K., de Vries A., Ossewaarde J. M. Chlamydia pneumoniae in abdominal aortic aneurysms: abundance of membrane components in the absence of heat shock protein 60 and DNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1999 Nov;19(11):2680–2686. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.19.11.2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moazed T. C., Kuo C., Grayston J. T., Campbell L. A. Murine models of Chlamydia pneumoniae infection and atherosclerosis. J Infect Dis. 1997 Apr;175(4):883–890. doi: 10.1086/513986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulder J. W. Interaction of chlamydiae and host cells in vitro. Microbiol Rev. 1991 Mar;55(1):143–190. doi: 10.1128/mr.55.1.143-190.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde J. M., Manten J. W., Hooft H. J., Hekker A. C. An enzyme immunoassay to detect specific antibodies to protein and lipopolysaccharide antigens of Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol Methods. 1989 Oct 24;123(2):293–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ossewaarde J. M., Meijer A. Molecular evidence for the existence of additional members of the order Chlamydiales. Microbiology. 1999 Feb;145(Pt 2):411–417. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-2-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puolakkainen M., Parker J., Kuo C. C., Grayston J. T., Campbell L. A. Further characterization of Chlamydia pneumoniae specific monoclonal antibodies. Microbiol Immunol. 1995;39(8):551–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1995.tb02241.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radinsky R., Bucana C. D., Ellis L. M., Sanchez R., Cleary K. R., Brigati D. J., Fidler I. J. A rapid colorimetric in situ messenger RNA hybridization technique for analysis of epidermal growth factor receptor in paraffin-embedded surgical specimens of human colon carcinomas. Cancer Res. 1993 Mar 1;53(5):937–943. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez J. A. Isolation of Chlamydia pneumoniae from the coronary artery of a patient with coronary atherosclerosis. The Chlamydia pneumoniae/Atherosclerosis Study Group. Ann Intern Med. 1996 Dec 15;125(12):979–982. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-12-199612150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saikku P., Leinonen M., Mattila K., Ekman M. R., Nieminen M. S., Mäkelä P. H., Huttunen J. K., Valtonen V. Serological evidence of an association of a novel Chlamydia, TWAR, with chronic coronary heart disease and acute myocardial infarction. Lancet. 1988 Oct 29;2(8618):983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90741-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sminia T., van der Brugge-Gamelkoorn G. J., Jeurissen S. H. Structure and function of bronchus-associated lymphoid tissue (BALT). Crit Rev Immunol. 1989;9(2):119–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stille W., Dittmann R., Just-Nübling G. Atherosclerosis due to chronic arteritis caused by Chlamydia pneumoniae: a tentative hypothesis. Infection. 1997 Sep-Oct;25(5):281–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01720397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson A. F., Kuo C. C. Evidence that the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis is glycosylated. Infect Immun. 1991 Jun;59(6):2120–2125. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.6.2120-2125.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theil D., Hoop R., Herring A. J., Pospischil A. Detection of Chlamydia in formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded avian tissue by in situ hybridization. A comparison between in situ hybridization and peroxidase-antiperoxidase labelling. Zentralbl Veterinarmed B. 1996 Aug;43(6):365–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0450.1996.tb00327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. P., Cummings P. K., Patton D. L., Kuo C. C. Ultrastructural lung pathology of experimental Chlamydia pneumoniae pneumonitis in mice. J Infect Dis. 1994 Aug;170(2):464–467. doi: 10.1093/infdis/170.2.464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. P., Kuo C. C., Grayston J. T. A mouse model of Chlamydia pneumoniae strain TWAR pneumonitis. Infect Immun. 1993 May;61(5):2037–2040. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2037-2040.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Y., Lyng K., Zhang Y. X., Rockey D. D., Morrison R. P. Monoclonal antibodies define genus-specific, species-specific, and cross-reactive epitopes of the chlamydial 60-kilodalton heat shock protein (hsp60): specific immunodetection and purification of chlamydial hsp60. Infect Immun. 1992 Jun;60(6):2288–2296. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2288-2296.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]