Abstract

Aims—To identify a model to assess general practitioner use of pathology services that could be applied to assess specific interventions designed to promote best practice.

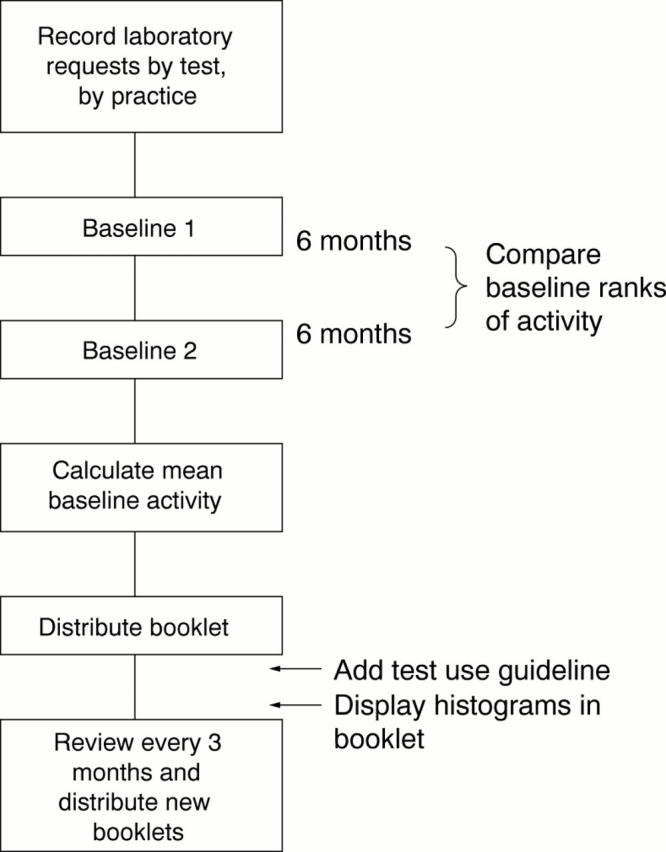

Methods—A database containing standardised requesting data for 22 general practices was constructed. The database contained 28 tests covering 95% of general practitioner activity, distributed across pathology, and it was evaluated during two sequential six month periods. A comparison of ranks of requesting activity between different time periods was undertaken by calculating Pearson rank correlation coefficients. Requesting numbers were also adjusted for patients' age and sex distributions within the 22 practices for a sample of three high volume tests. The effects of distributing requesting guidelines and details of requesting activity were assessed during two sequential three month periods.

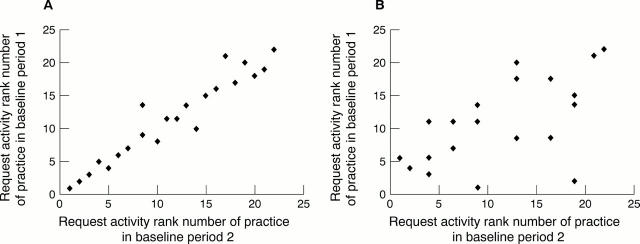

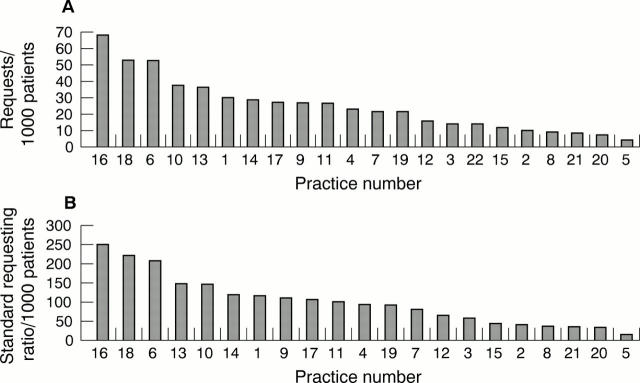

Results—Requesting activity was extremely stable during the two baseline periods for most tests (r > 0.80 for 20 of the 28 tests). Several less discriminatory tests were identified. Age and sex adjustment had minimal impact on the ranks of requesting activity. Requesting activity during the two three month periods after distributing guidelines and comparative details of individual requesting activity showed little change (overall correlation coefficient, 0.844 between baseline and intervention periods).

Conclusion—Ranking general practitioners requesting activity adjusted for practice list size provides a reproducible means of measuring requesting activity for most pathology tests performed in general practice. Activity was not influenced by age or sex of patients on the practice list. Distributing requesting guidelines and individual requesting activity on their own do not have any measurable impact on requesting activity. More innovative (possibly multiple) interventions might be required to influence general practitioner requesting practice.

Key Words: benchmarking • appropriateness • clinical governance

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (129.9 KB).

Figure 1 Study design.

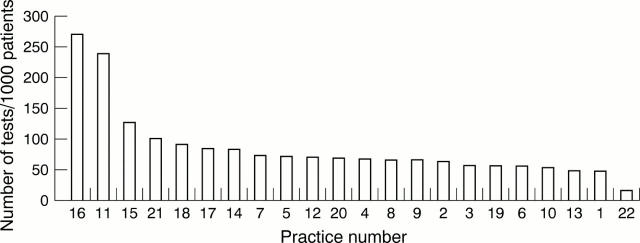

Figure 2 Sample graphical display of requesting figures (April to October 1997) for cholesterol for each 1000 patients on the general practitioner practice list for 22 general practices (numbered 1–22). Cholesterol screening is indicated in patients with established coronary heart disease, in primary prevention patients over 35 years of age, and in all patients with a family history of hypercholesterolaemia. Borderline results should be repeated annually, but acceptable results need not be repeated more frequently than every five years in primary prevention. On treatment follow up should be three monthly until targets are met, and six monthly thereafter. High users should consider whether they are screening patients that they are unlikely to treat. Category of evidence: consultant opinion from national guidelines and randomised controlled trials.

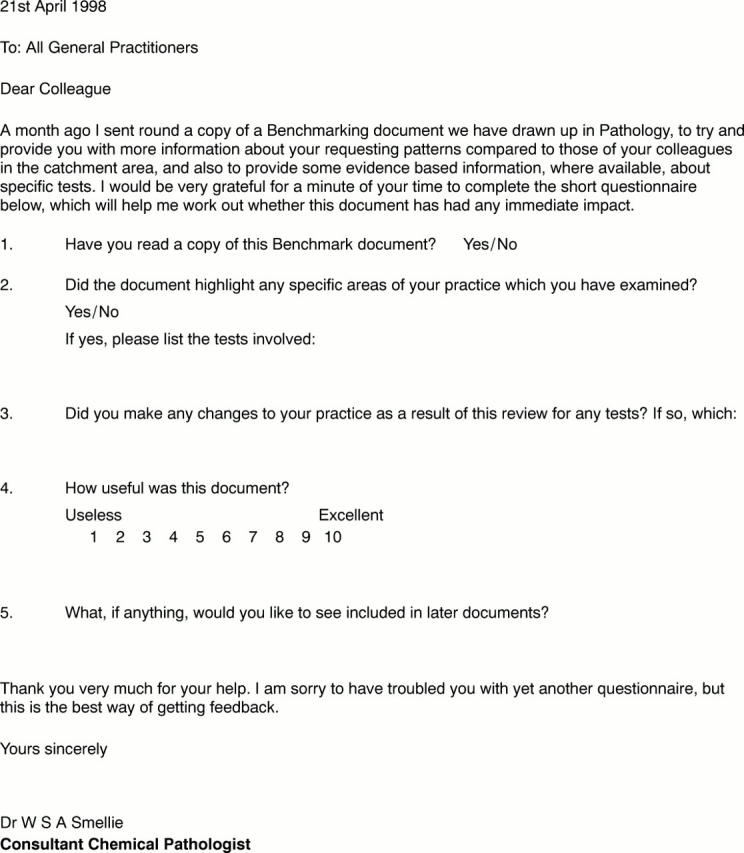

Figure 3 The questionnaire. This questionnaire was sent to each practice one month after the distribution of activity booklets to assess users' reactions to the data, and to record any changes described in response to the data.

Figure 4 Scatter plot for rankings of requesting activity for each 1000 patients for 22 practices during two six month baseline periods. (A) Highly discriminatory test (glucose); (B) poorly discriminatory test (rheumatoid factor).

Figure 5 The influence of age/sex adjustment on the distribution of requests for glucose tests in 22 practices (numbered 1–22). (A) Crude rates; (B) standard requesting ratio (adjusted for age and sex).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Benge H., Bodor G. S., Younger W. A., Parl F. F. Impact of managed care on the economics of laboratory operation in an academic medical center. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1997 Jul;121(7):689–694. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming K. A. Evidence-based pathology. J Pathol. 1996 Jun;179(2):127–128. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199606)179:2<127::AID-PATH519>3.0.CO;2-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R. A. Evidence-based clinical biochemistry. Ann Clin Biochem. 1997 Jan;34(Pt 1):3–7. doi: 10.1177/000456329703400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon D. H., Hashimoto H., Daltroy L., Liang M. H. Techniques to improve physicians' use of diagnostic tests: a new conceptual framework. JAMA. 1998 Dec 16;280(23):2020–2027. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Walraven C., Goel V., Chan B. Effect of population-based interventions on laboratory utilization: a time-series analysis. JAMA. 1998 Dec 16;280(23):2028–2033. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.23.2028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Walraven C., Naylor C. D. Do we know what inappropriate laboratory utilization is? A systematic review of laboratory clinical audits. JAMA. 1998 Aug 12;280(6):550–558. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.6.550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]