Abstract

Aims—Patients without spleens are at increased risk of overwhelming infection. Recently, greater efforts, including the publication of national guidelines, have been made to improve the management of asplenic individuals. In theory, risks of serious sepsis can be reduced by good advice, immunisation, and antibiotic prophylaxis. In practice, such preventive measures might not be followed or may fail. A study of recent cases of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI) was undertaken to examine specific associated factors and to determine whether currently recommended preventive measures are being followed.

Methods—Cases of OPSI were identified and reported mainly by microbiologists across the country using a specifically designed proforma. Data including the nature of the infection and vaccination/antibiotic prophylaxis history since splenectomy were obtained.

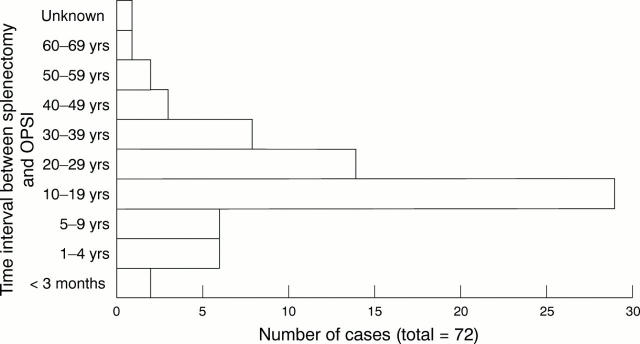

Results—Seventy seven cases were reported. The age range varied from 3 months (congenital asplenia) to 87 years. In those who had undergone surgical splenectomy, the time interval between surgery and OPSI varied from 24 days to 65 years. Overall mortality reached 50%, with underlying haematological malignancy associated with the highest death rate. Streptococcus pneumoniae caused approximately 90% episodes. Only 31% individuals had received pneumococcal vaccination before OPSI. Seven of 17 pneumococcal infections in immunised cases could be considered vaccine failures. Few patients had been adequately advised on antibiotic prophylaxis or other measures.

Conclusions—Currently accepted best practice for managing asplenic patients is not being followed. Some OPSI cases may still be preventable but many asplenic individuals remain unrecognised. The compilation of asplenic patient registers might help to implement agreed policies with audit necessary to evaluate compliance. More is needed to ensure optimal management for this cohort of the population.

Key Words: splenectomy • immunisation • overwhelming postsplenectomy infection • asplenic patient register

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (140.1 KB).

Figure 1 Time interval between splenectomy and sepsis in 72 cases of overwhelming postsplenectomy infection (OPSI).

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Abildgaard N., Nielsen J. L. Pneumococcal septicaemia and meningitis in vaccinated splenectomized adult patients. Scand J Infect Dis. 1994;26(5):615–617. doi: 10.3109/00365549409011821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullingford G. L., Watkins D. N., Watts A. D., Mallon D. F. Severe late postsplenectomy infection. Br J Surg. 1991 Jun;78(6):716–721. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding A. K. Prophylaxis against late infection following splenectomy and bone marrow transplant. Blood Rev. 1994 Sep;8(3):179–191. doi: 10.1016/0268-960x(94)90079-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch R. G., Read R. Long-term management after splenectomy. ... and may be ineffective. BMJ. 1994 Jan 8;308(6921):132–132. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6921.132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazlewood M., Kumararatne D. S. The spleen? Who needs it anyway? Clin Exp Immunol. 1992 Sep;89(3):327–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1992.tb06956.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenks Peter J., Jones Eleri. Infections in asplenic patients. Clin Microbiol Infect. 1996 Jun;1(4):266–272. doi: 10.1016/s1198-743x(15)60286-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassianos G. C. Managing patients with an absent or dysfunctional spleen. Uncertainty exists over frequency of blood tests to test antipneumococcal immunity. BMJ. 1996 May 25;312(7042):1360–1361. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7042.1360c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind E. A., Craft C., Fowles J. B., McCoy C. E. Pneumococcal vaccine administration associated with splenectomy: missed opportunities. Am J Infect Control. 1998 Aug;26(4):418–422. doi: 10.1016/s0196-6553(98)70038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klinge J., Hammersen G., Scharf J., Lütticken R., Reinert R. R. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection with vaccine-type Streptococcus pneumoniae in a 12-year-old girl despite vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis. Infection. 1997 Nov-Dec;25(6):368–371. doi: 10.1007/BF01740820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konradsen H. B., Henrichsen J. Pneumococcal infections in splenectomized children are preventable. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1991 Apr;80(4):423–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1991.tb11877.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long S. G., Smith A. G., Perry B. A., Leyland M. J., Milligan D. W. Implementing a policy for pneumococcal prophylaxis in a haematology unit after splenectomy. Qual Health Care. 1995 Sep;4(3):194–196. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.3.194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch A. M., Kapila R. Overwhelming postsplenectomy infection. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1996 Dec;10(4):693–707. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70322-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacInnes J., Waghorn D. J., Haworth E. Management of asplenic patients in South Buckinghamshire: an audit of local practice. Commun Dis Rep CDR Rev. 1995 Nov 10;5(12):R173–R177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong E. L., Hassan I. S., Snow M. H. Pneumococcal sepsis in a splenectomized patient. Br J Gen Pract. 1995 Sep;45(398):502–503. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen C., Ejstrud P., Hansen J. B., Konradsen H. B. Asplenic patients' knowledge of prophylactic measures against severe infections. Clin Infect Dis. 1997 Sep;25(3):738–738. doi: 10.1086/516937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read R. C., Finch R. G. Prophylaxis after splenectomy. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994 Jan;33(1):4–6. doi: 10.1093/jac/33.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarangi J., Coleby M., Trivella M., Reilly S. Prevention of post splenectomy sepsis: a population based approach. J Public Health Med. 1997 Jun;19(2):208–212. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz P. E., Sterioff S., Mucha P., Melton L. J., 3rd, Offord K. P. Postsplenectomy sepsis and mortality in adults. JAMA. 1982 Nov 12;248(18):2279–2283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shann F. Modern vaccines. Pneumococcus and influenza. Lancet. 1990 Apr 14;335(8694):898–901. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90489-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw J. H., Print C. G. Postsplenectomy sepsis. Br J Surg. 1989 Oct;76(10):1074–1081. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800761029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spelman D. W. Postsplenectomy overwhelming sepsis: reducing the risks. Med J Aust. 1996 Jun 3;164(11):648–648. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1996.tb122231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spickett G. P., Bullimore J., Wallis J., Smith S., Saunders P. Northern region asplenia register--analysis of first two years. J Clin Pathol. 1999 Jun;52(6):424–429. doi: 10.1136/jcp.52.6.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn D. J., Haworth E. Avoiding infection after splenectomy. Br J Gen Pract. 1996 Nov;46(412):691–691. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waghorn D. J. Prevention of postsplenectomy sepsis. Lancet. 1993 Jan 23;341(8839):248–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]