Abstract

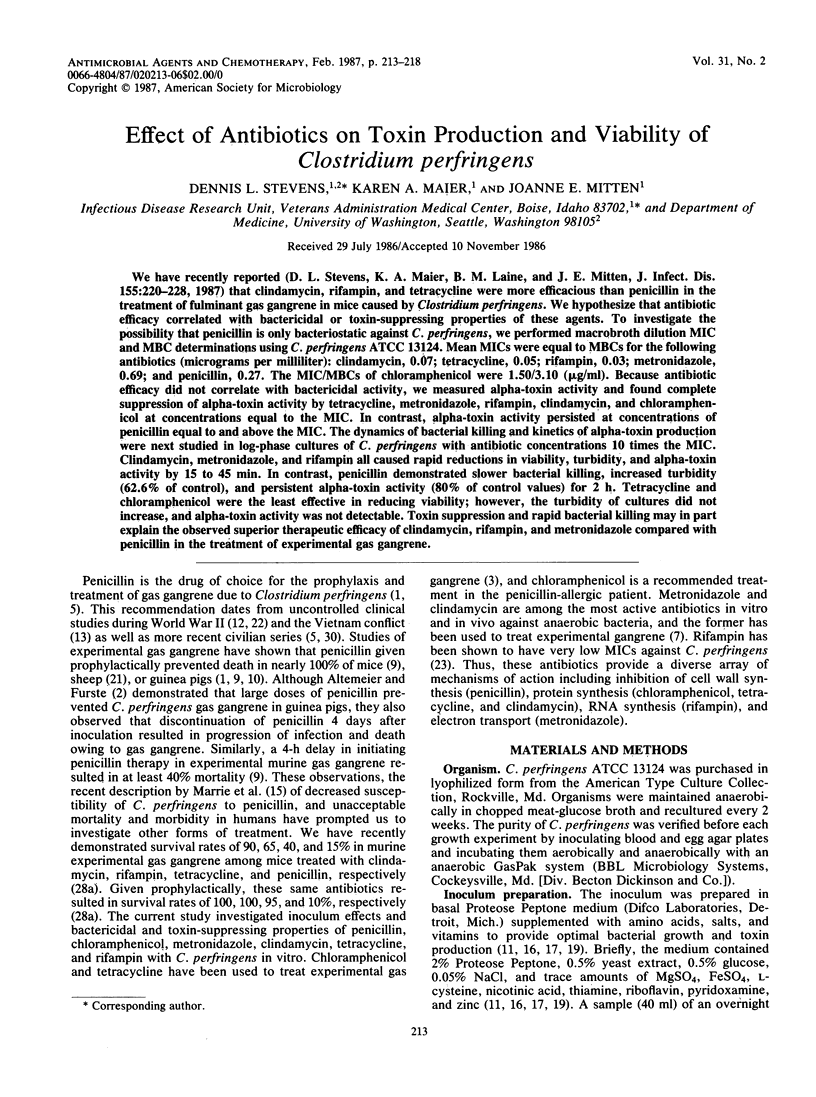

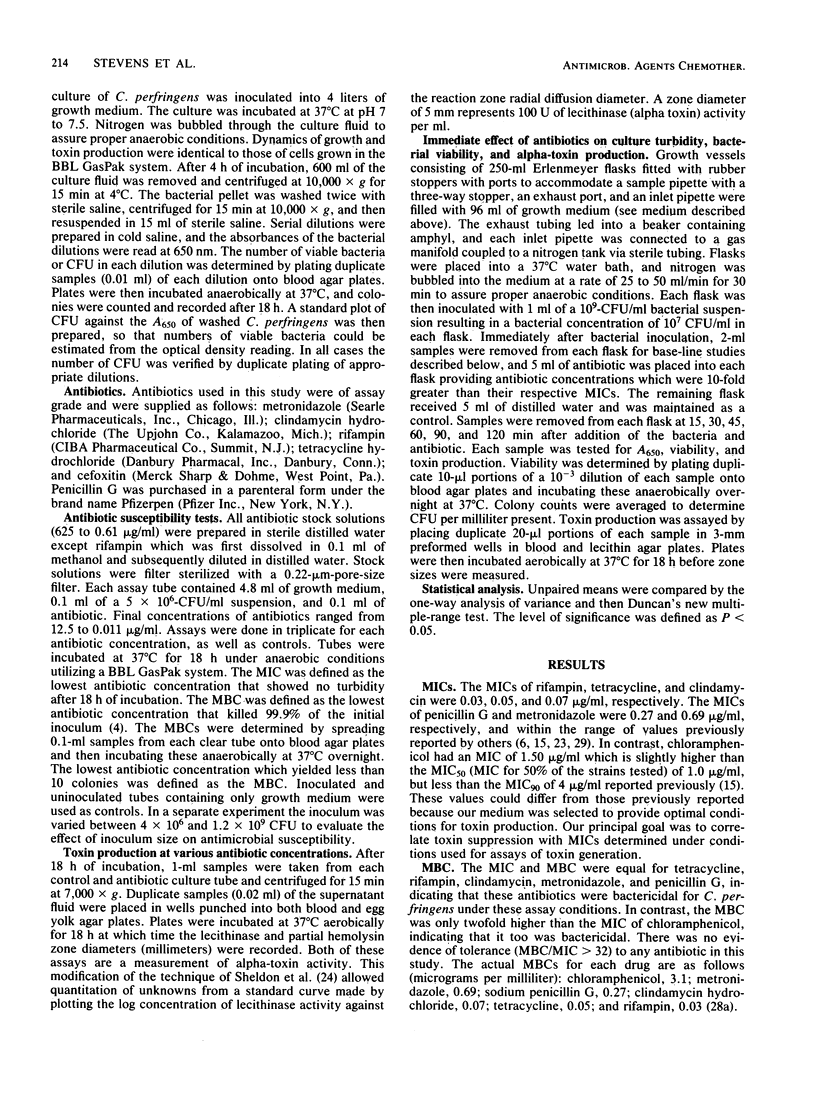

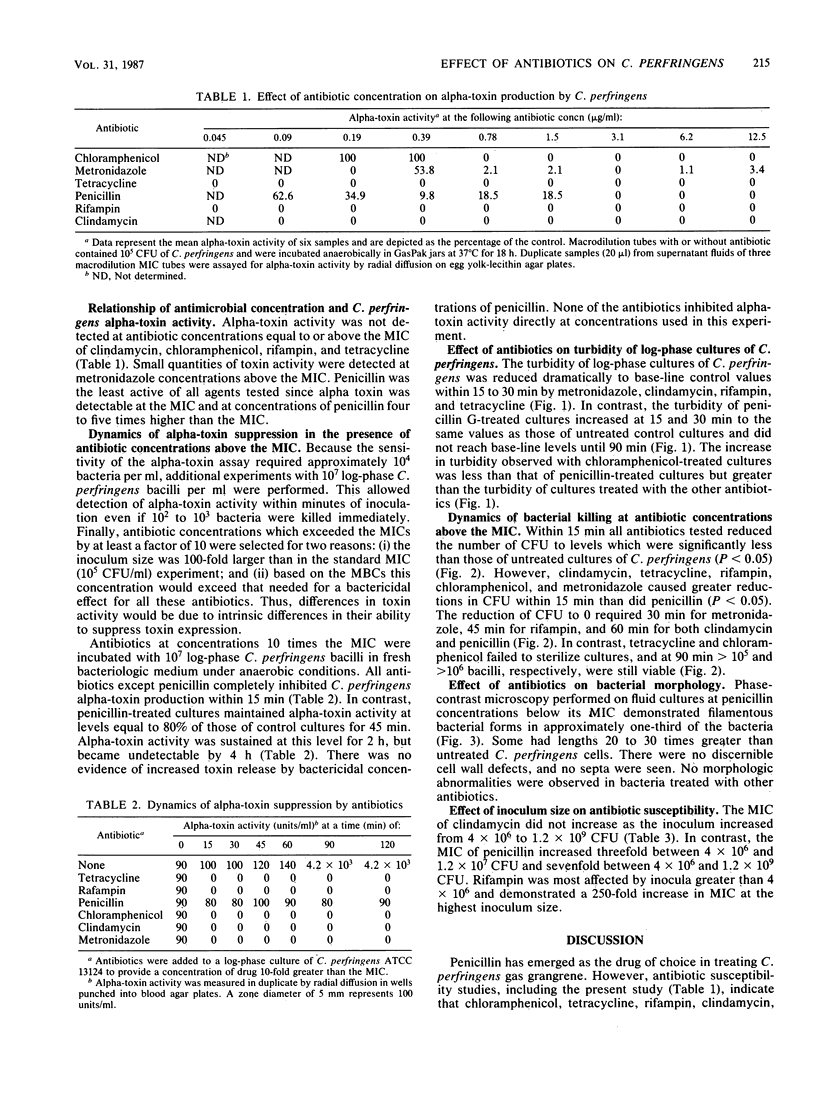

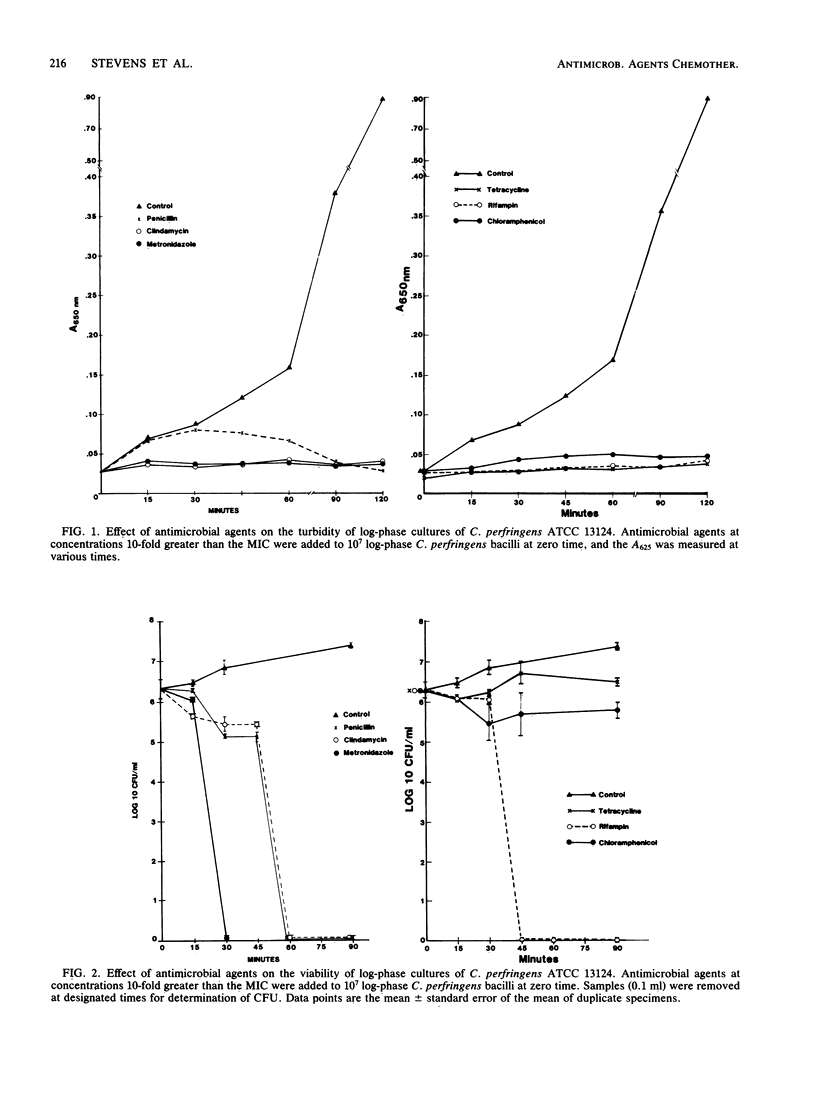

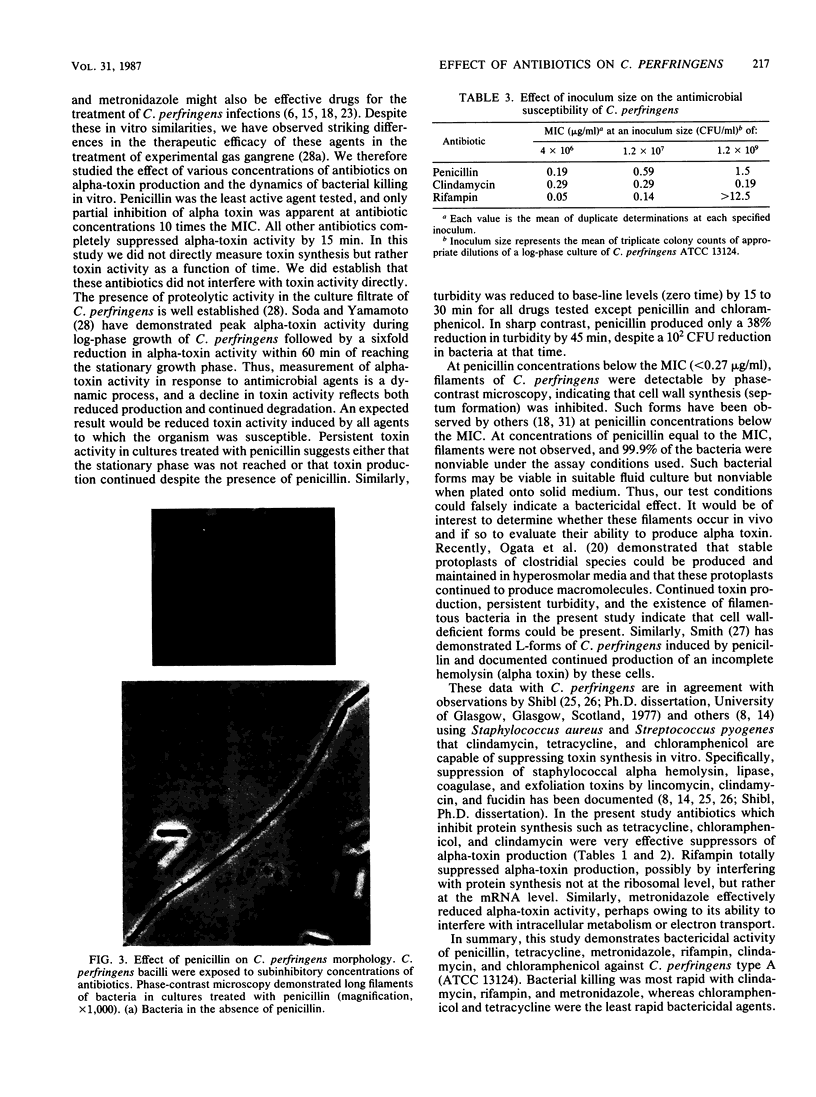

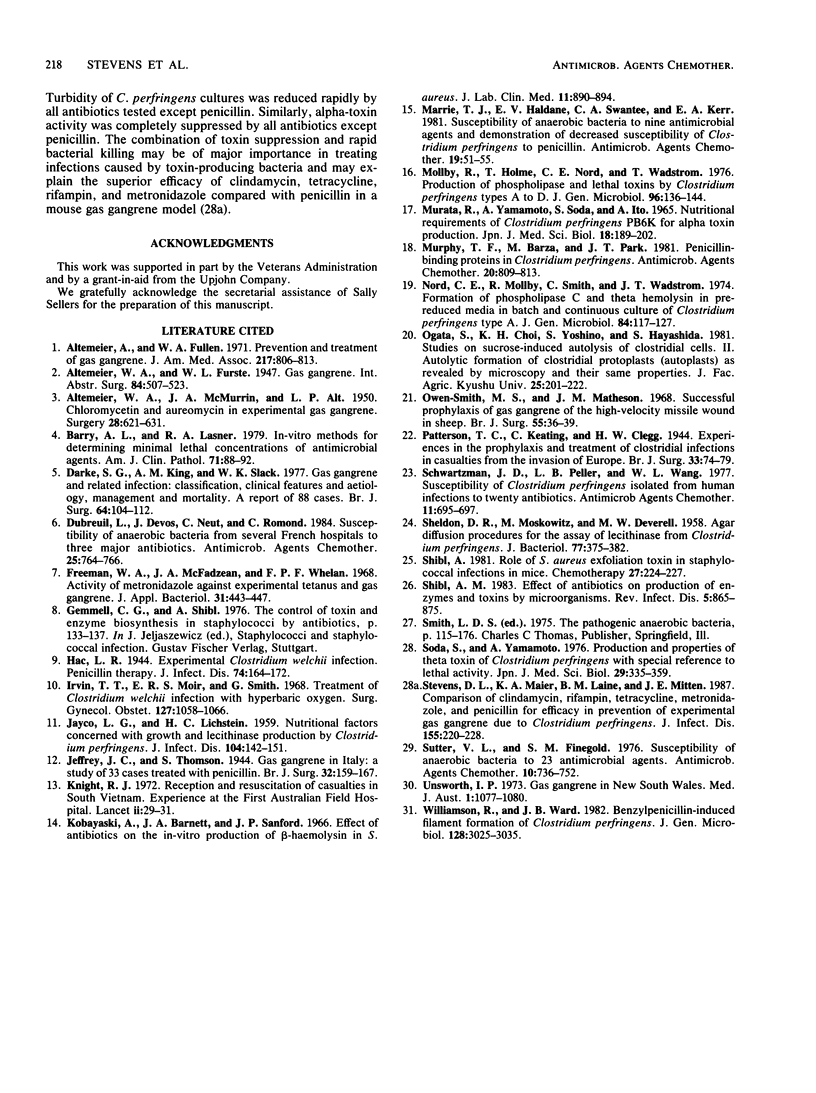

We have recently reported (D.L. Stevens, K.A. Maier, B.M. Laine, and J.E. Mitten, J. Infect. Dis. 155:220-228, 1987) that clindamycin, rifampin, and tetracycline were more efficacious than penicillin in the treatment of fulminant gas gangrene in mice caused by Clostridium perfringens. We hypothesize that antibiotic efficacy correlated with bactericidal or toxin-suppressing properties of these agents. To investigate the possibility that penicillin is only bacteriostatic against C. perfringens, we performed macrobroth dilution MIC and MBC determinations using C. perfringens ATCC 13124. Mean MICs were equal to MBCs for the following antibiotics (micrograms per milliliter): clindamycin, 0.07; tetracycline, 0.05; rifampin, 0.03; metronidazole, 0.69; and penicillin, 0.27. The MIC/MBCs of chloramphenicol were 1.50/3.10 (micrograms/ml). Because antibiotic efficacy did not correlate with bactericidal activity, we measured alpha-toxin activity and found complete suppression of alpha-toxin activity by tetracycline, metronidazole, rifampin, clindamycin, and chloramphenicol at concentrations equal to the MIC. In contrast, alpha-toxin activity persisted at concentrations of penicillin equal to and above the MIC. The dynamics of bacterial killing and kinetics of alpha-toxin production were next studied in log-phase cultures of C. perfringens with antibiotic concentrations 10 times the MIC. Clindamycin, metronidazole, and rifampin all caused rapid reductions in viability, turbidity, and alpha-toxin activity by 15 to 45 min. In contrast, penicillin demonstrated slower bacterial killing, increased turbidity (62.6% of control), and persistent alpha-toxin activity (80% of control values) for 2 h. Tetracycline and chloramphenicol were the least effective in reducing viability; however, the turbidity of cultures did not increase, and alpha-toxin activity was not detectable. Toxin suppression and rapid bacterial killing may in part explain the observed superior therapeutic efficacy of clindamycin, rifampin, and metronidazole compared with penicillin in the treatment of experimental gas gangrene.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- ALTEMEIER W. A., McMURRIN J. A., ALT L. P. Chloromycetin and aureomycin in experimental gas gangrene. Surgery. 1950 Oct;28(4):621–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altemeier W. A., Fullen W. D. Prevention and treatment of gas gangrene. JAMA. 1971 Aug 9;217(6):806–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barry A. L., Lasner R. A. In-vitro methods for determining minimal lethal concentrations of antimicrobial agents. Am J Clin Pathol. 1979 Jan;71(1):88–92. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/71.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darke S. G., King A. M., Slack W. K. Gas gangrene and related infection: classification, clinical features and aetiology, management and mortality. A report of 88 cases. Br J Surg. 1977 Feb;64(2):104–112. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800640207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubreuil L., Devos J., Neut C., Romond C. Susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria from several French hospitals to three major antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1984 Jun;25(6):764–766. doi: 10.1128/aac.25.6.764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman W. A., McFadzean J. A., Whelan J. P. Activity of metronidazole against experimental tetanus and gas gangrene. J Appl Bacteriol. 1968 Dec;31(4):443–447. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.1968.tb00393.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvin T. T., Moir E. R., Smith G. Treatment of Clostridium welchii infection with hyperbaric oxygen. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1968 Nov;127(5):1058–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAYKO L. G., LICHSTEIN H. C. Nutritional factors concerned with growth and lecithinase production by Clostridium perfringens. J Infect Dis. 1959 Mar-Apr;104(2):142–151. doi: 10.1093/infdis/104.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight R. J. Reception and resuscitation of casualties in South Vietnam. Experience at the First Australian Field Hospital. Lancet. 1972 Jul 1;2(7766):29–31. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)91287-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrie T. J., Haldane E. V., Swantee C. A., Kerr E. A. Susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to nine antimicrobial agents and demonstration of decreased susceptibility of Clostridium perfringens to penicillin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Jan;19(1):51–55. doi: 10.1128/aac.19.1.51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy T. F., Barza M., Park J. T. Penicillin-binding proteins in Clostridium perfringens. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1981 Dec;20(6):809–813. doi: 10.1128/aac.20.6.809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Möllby R., Holme T., Nord C. E., Smyth C. J., Wadström T. Production of phospholipase C (alpha-toxin), haemolysins and lethal toxins by Clostridium perfringens types A to D. J Gen Microbiol. 1976 Sep;96(1):137–144. doi: 10.1099/00221287-96-1-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nord C. E., Möllby R., Smyth C., Wadström T. Formation of phospholipase C and theta-haemolysin in pre-reduced media in batch anc continuous culture of Clostridium perfringens type A. J Gen Microbiol. 1974 Sep;84(1):117–127. doi: 10.1099/00221287-84-1-117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen-Smith M. S., Matheson J. M. Successful prophylaxis of gas gangrene of the high-velocity missile wound in sheep. Br J Surg. 1968 Jan;55(1):36–39. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800550111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHELDON D. R., MOSKOWITZ M., DEVERELL M. W. Agar diffusion procedures for the assay of lecithinase from Clostridium perfringens. J Bacteriol. 1959 Apr;77(4):375–382. doi: 10.1128/jb.77.4.375-382.1959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartzman J. D., Reller L. B., Wang W. L. Susceptibility of Clostridium perfringens isolated from human infections to twenty antibiotics. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1977 Apr;11(4):695–697. doi: 10.1128/aac.11.4.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibl A. M. Effect of antibiotics on production of enzymes and toxins by microorganisms. Rev Infect Dis. 1983 Sep-Oct;5(5):865–875. doi: 10.1093/clinids/5.5.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibl A. M. Role of Staphylococcus aureus exfoliatin toxin in staphylococcal infections in mice. Chemotherapy. 1981;27(3):224–227. doi: 10.1159/000237982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soda S., Ito A., Yamamoto A. Production and properties of theta-toxin of Clostridium perfringens with special reference to lethal activity. Jpn J Med Sci Biol. 1976 Dec;29(6):335–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens D. L., Maier K. A., Laine B. M., Mitten J. E. Comparison of clindamycin, rifampin, tetracycline, metronidazole, and penicillin for efficacy in prevention of experimental gas gangrene due to Clostridium perfringens. J Infect Dis. 1987 Feb;155(2):220–228. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutter V. L., Finegold S. M. Susceptibility of anaerobic bacteria to 23 antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1976 Oct;10(4):736–752. doi: 10.1128/aac.10.4.736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unsworth I. P. Gas gangrene in New South Wales. Med J Aust. 1973 Jun 2;1(22):1077–1080. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1973.tb110943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson R., Ward J. B. Benzylpenicillin-induced filament formation of Clostridium perfringens. J Gen Microbiol. 1982 Dec;128(12):3025–3035. doi: 10.1099/00221287-128-12-3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]