Abstract

RNA interference (RNAi) has emerged as a powerful tool to generate loss-of-function phenotypes in a variety of organisms. Combined with the sequence information of almost completely annotated genomes, RNAi technologies have opened new avenues to conduct systematic genetic screens for every annotated gene in the genome. As increasing large datasets of RNAi-induced phenotypes become available, an important challenge remains the systematic integration and annotation of functional information. Genome-wide RNAi screens have been performed both in Caenorhabditis elegans and Drosophila for a variety of phenotypes and several RNAi libraries have become available to assess phenotypes for almost every gene in the genome. These screens were performed using different types of assays from visible phenotypes to focused transcriptional readouts and provide a rich data source for functional annotation across different species. The GenomeRNAi database provides access to published RNAi phenotypes obtained from cell-based screens and maps them to their genomic locus, including possible non-specific regions. The database also gives access to sequence information of RNAi probes used in various screens. It can be searched by phenotype, by gene, by RNAi probe or by sequence and is accessible at http://rnai.dkfz.de

INTRODUCTION

RNA interference (RNAi) has opened new avenues for the systematic analysis of phenotypes. With the completion of many whole genome sequences, RNAi allows the depletion of gene products in a wide range of organisms, thus enabling reverse genetic approaches where genetic tools are lacking. The molecular mechanism of RNAi-mediated gene silencing is conserved from plants to higher animals and studies in many organisms have benefited tremendously from the availability of RNAi libraries. Compared to classical genetic screens, RNAi has the advantage to provide a link from phenotype to gene without the need for positional cloning of mutant alleles, but it lacks the possibility to make stable mutations and may display non-specific off-target effects.

Depending on the experimental system, RNAi approaches are amenable for high-throughput screening, thereby allowing complete genomes to be queried for specific phenotypes. Screens can be performed for whole organism phenotypes, which has been done in Caenorhabditis elegans (1,2). Cell-based RNAi experiments have become widely used in particular in Drosophila and to a smaller extent in vertebrates, organisms for which many cell lines are available (3–6). Cell-based phenotypes can be measured using simple fluorescent or luminescence reporters or more complex phenotypes as can be detected by immunofluorescence and microscopy (7). However each phenotypic readout method has its specific analysis method and a generally accepted ontology for phenotypes is still missing.

In the past few years different RNAi libraries have been constructed that cover large parts of many genomes. For invertebrates, such as C.elegans and Drosophila, libraries can be produced relatively cheaply, since long double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) can be generated by in vitro transcription. In addition, use of dsRNA in these organisms does not elicit an interferon response (8,9). Expression of dsRNA in bacteria that are fed to C.elegans is sufficient to produce an efficient knock-down of target transcripts (9). In Drosophila cells, simple addition of long dsRNA to the cell culture medium is sufficient for cells to take up the dsRNAs and intracellularly dice them in many different 21–23 bp siRNAs (8). The efficiency of RNAi in invertebrates is likely due to the diversity of siRNA species that are intracellularly produced.

Drosophila cell-based assays are widely used since the genome is well-annotated and many cellular pathways are conserved from flies to man (10,11). Moreover, Drosophila lacks a redundancy of factors often found in mammalian genomes. For example, depleting Dsh by RNAi is sufficient to fully recapitulate a Wg loss-of-function phenotype, whereas it is necessary to deplete all three homologs (Dvl1–3) in human cells to observe a Wnt phenotype (D. Ingelfinger and M. Boutros, unpublished data). Such examples occur in many cellular pathways and it might be necessary in mammalian cells to pool RNAi reagents for multiple candidates to generate a loss-of-function phenotype. While this is technically possible, it will significantly increase the complexity of screens.

More than 20 genome-wide (or genome-scale) screens in Drosophila cells have been published since 2003 and a key challenge remains to integrate and compare different datasets. Since many screens have been performed using different RNAi libraries and readouts, a proper annotation using minimal information for RNAi experiments would be required. The equivalent of a MIAME convention is currently lacking and the breadth and quality of data provided for screens varies. Data structures and databases will be needed to cross-correlate phenotypic information.

As large-scale studies remain largely untested in follow-up experiments for a certain period of time, it is crucial to systematically integrate phenotypes and annotation information to estimate false positive and false negative rates. A comparison across multiple screens can also be used to evaluate the reliability of a phenotype or a particular RNAi reagent used in these studies. Ultimately, phenotypic profiles of many screens can serve to cluster unknown genes and provide guideposts for follow-up analysis (12). Since most cell-based RNAi screens have been published using Drosophila RNAi libraries, these screens can serve as a model for the organization of data produced in large-scale RNAi experiments.

Here we describe a publicly accessible database to integrate annotation of RNAi reagents and functional information obtained from large-scale RNAi experiments. The database allows the user to access phenotype data from published screens and the sequences of their underlying perturbation reagents. Specificity and other sequence features are displayed in the context of the genomic location of the targeted gene model. GenomeRNAi also facilitates the design of new experiments, using previously designed RNAi reagents from independent libraries and links to a design program of RNAi constructs for independent retests (13). The database structure is flexible and allows adding large-scale cell-based phenotypic datasets from other organisms once they become available.

DATABASE CONTENT

The database integrates the sequence information of the RNAi reagents with phenotypic information based on genome-scale and genome-wide published RNAi screens. It contains 90 998 RNAi probes that have been designed by various groups. These include libraries used in Heidelberg and Boston (4,14), by groups in San Francisco and others (15). Using the sequence information, all RNAi constructs were computationally mapped onto the latest genomic sequence using BLAST and MUMmer (16,17) and gene and isoform annotations were derived through the mapping process. All probe information is visualized using an implementation of the Generic Genome Browser (GBrowse) (18). Additional information was added to describe the specificity of dsRNAs. To this end, we have generated all possible 19mer sequences of annotated gene models (in total >40 Mio.) and identified homologous sequences in the complete genome. These are annotated as ‘tracks’ in GBrowse and allow evaluation of the specificity of RNAi probe sequences. In addition, GBrowse tracks are included that show other types of non-specific regions, such as low complexity and repetitive elements in the gene model which should be avoided in the design of RNAi probes. Phenotypes mapping to such elements should also be treated with caution until further confirmatory data is available. Furthermore, for every single 19mer sequence we have calculated an RNAi efficiency score (19) which is shown as a ‘RNAi efficiency’ column in the database. The average predicted efficiency is shown for individual RNAi probes from various libraries as well as a ‘track’ for complete gene models in the GBrowse interface. Specificity and efficiency information can also be used to guide the design of new RNAi probes for follow-up experiments.

RNAi phenotypes of large-scale screens from our own lab and all to-date published screens were curated from the author's websites or the Supplementary Data. To date, the database contains 24 genome-scale screens which were performed with different genome-wide and subset RNAi libraries. A total of 5436 phenotypes are currently stored in GenomeRNAi, which will be expanded as more data becomes available. Phenotype frequency varies among the screens from 23 to >1000 hits per screen. A list of all currently available screens can be accessed at http://www.dkfz.de/signaling/screens/.

DATA QUERY

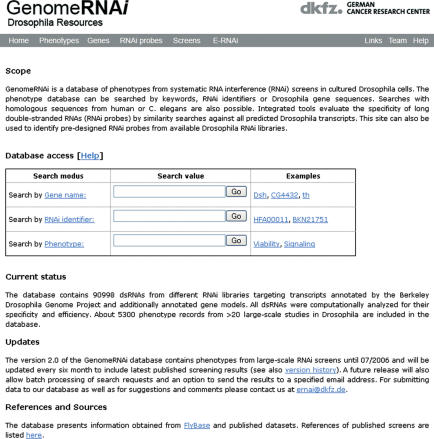

The database can be accessed through various routes. Individual gene entries can be directly accessed via a linkout (‘Heidelberg RNAi’) from Flybase (20). From the entry webpage of the database, user can search by gene identifier, by RNAi probe ID (if known) or by phenotype (Figure 1). For all these search options more detailed web pages are available which offer advanced input options (e.g. sequence homology search). Through the ‘phenotype’ entry page a complete list of all phenotypes can be requested by clicking the ‘Display list of all phenotypes’ link. This can then be used to access an individual gene or probe list. A second way to search for phenotypes and RNAi probe information is by sequence similarity. In the ‘Gene’ or ‘Probe’ menu page, the user can enter a Drosophila (or heterologous) nucleotide or protein sequence which is mapped by using BLAST against the BDGP transcript file or probe files. This allows for example to search for phenotypes of a homolog of human cdc2 or can be used to find all RNAi probes from various libraries that overlap with a query sequence.

Figure 1.

Entry page of the GenomeRNAi database. This page allows direct access to search function by gene, RNAi ID or phenotype. More detailed search pages which allow for example to search by sequence homology can be accessed via the main menu.

DATA OUTPUT

Information with respect to genes or RNAi probes is subsequently retrieved from the database. In case of gene query, the database retrieves all mapped RNAi probes and displays them as a table (Figure 2A), including information of phenotypes that were reported, the calculated target transcripts and whether all isoforms are targeted (columns ‘Transcripts’ and ‘Specificity’). This view shows also how many in silico diced siRNAs map to gene model and whether additional transcripts are targeted (column ‘Other Targets’) by the dsRNA. The database allows then to drill down and retrieve more detailed information, including primer and amplicon sequences (Figure 2B) by following the ‘RNAi probe’ link as well as more detailed information on other targets by following the corresponding link. The completeness of available RNAi constructs in their genomic context is summarized in an interactive GBrowse implementation, which shows the gene model, the RNAi probes of all available libraries and tracks that allow evaluating the efficiency and specificity of probe sequences (Figure 2C). Other GBrowse functions can then be used to extract for example non-targeted regions, common exons, regions with high specificity or regions of low-complexity. Information can be extracted as text or XML files.

Figure 2.

Example of a database search using the Web interface. (A) The table shows the search results from a user query for all probes targeting the CG6210 transcripts. The ‘Specificity’ column summarizes how many of the theoretical possible diced 21mer sequences hit the transcript. (B) Drill down to access sequence information associated with a particular RNAi probe. This information can also be used to redesign RNAi reagents. (C) GBrowse image of all RNAi probes that target a particular gene model. Different libraries are shown in tracks. Specificity and other information are shown below the RNAi probes. If RNAi probes target other genes in addition to the intended one, this information is displayed below the RNAi probes [e.g. FBgn0036141 (CG6210) + 24 other targets].

An example of a database session is shown in Figure 2. In this case, the user searched for RNAi probes that target CG6210 (FBgn0036141), a factor required for the secretion of Wg/Wnt ligands (3). Figure 2A shows that multiple RNAi probes are available in different libraries and also links to FlyBase, if more information on CG6210 is requested. When the user selects the HFA10605 RNAi probe, the database shows more detailed information, such as primer sequences used to amplify a template for in vitro transcription, the length and sequence of the amplicon. This page also shows all other phenotypes that were observed with this RNAi probe, allowing evaluation of the specificity of the RNAi experiment. When selecting the GBrowse image, the user can locate other RNAi probes in relation to the gene model; for example, whereas for CG6210 six dsRNAs from different libraries have a similar location, a single dsRNA (‘AMC-Amplicon’) targets only one splice variant (CG6210-RA) and might give only a partial phenotype. These assignments are even more complex for gene models that have a larger number of splice variants and/or overlapping transcripts.

The database can also be accessed through searching for phenotypes or selecting from an all phenotypes list which can be retrieved from phenotype search menu.

Through these pages, the database provides gene annotation by comparing phenotypes in the light of the sequence content of probes targeting the gene of interest. Furthermore, individual gene models are linked to external databases such as FlyBase and FLIGHT for other functional information. A link to E-RNAi (13) is provided to allow a direct redesign of independent RNAi probes.

CONCLUSIONS AND OUTLOOK

The GenomeRNAi database presents phenotype information of large-scale screens in the context of associated sequence information. We believe that this is an important issue since in contrast to genetic mutants, RNAi phenotypes depend on the specificity of the used siRNAs or dsRNAs (21–23). Furthermore, with changes in gene models, RNAi phenotypes attributed to a specific gene may be linked to a different gene in the future. Similar limitations apply to RNAi reagents targeting specific splice variants of genes. RNAi libraries evolve, as we learn more about the RNAi mechanism and potential pitfalls such as off-target effects second generation libraries will incorporate these findings into design rules and attempt to generate more specific reagents and make them publicly available (T. Horn, A. Kiger, M. Boutros, unpublished data).

The GenomeRNAi database is linked to other databases, such as FLIGHT and FlyRNAi (24,25). While all these databases contain RNAi phenotype information, the focus of GenomeRNAi is to present phenotypes in the context of genomic information, which should facilitate the analysis of RNAi phenotypes with respect to gene models and specificity information. GenomeRNAi has an integrated pipeline for mapping of RNAi probes and phenotypes and integrating the information of different RNAi libraries, but the focus is less on the integration of different genomic datasets as provided by FLIGHT.

A major issue in representing RNAi phenotypes remains a lack of standards on minimal information which need to be provided for small and large-scale screening approaches, as well as an ontology to properly describe cellular phenotypes. With time we expect that the community will develop such standards which will become a prerequisite for publication. The same holds true for the analysis of numerical data associated with phenotypic information, which can be analyzed in different ways and which may lead to different ‘phenotype lists’ depending on the arbitrary threshold that is being used as a cut-off. Compendia that include both primary data and the analysis route could alleviate analysis diversity and enable the re-analysis of datasets when new algorithms will be available or datasets will be cross-correlated (26,27).

In the future, we plan to add cell-based phenotypes from other species, such as human, including sequence information which is currently largely not available due to proprietary restrictions. Cross-specific comparisons should provide a useful means to extract functional and highly confirmed phenotypes.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available at NAR online.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Anan Ragab, David Kuttenkeuler, Dorothee Nickles, Florian Fuchs and Sandra Steinbrink for helpful comments on the manuscript and members of the Boutros lab for critical suggestions and discussions throughout the project. We are grateful to Tobias Reber for support with server infrastructure. T.H. was supported by a fellowship of the Studienstiftung des deutschen Volkes. The research was funded by the Emmy Noether Program of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and a Research Grant of the Human Frontier Science Program to M.B.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kamath R.S., Fraser A.G., Dong Y., Poulin G., Durbin R., Gotta M., Kanapin A., Le Bot N., Moreno S., Sohrmann M., et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sonnichsen B., Koski L.B., Walsh A., Marschall P., Neumann B., Brehm M., Alleaume A.M., Artelt J., Bettencourt P., Cassin E., et al. Full-genome RNAi profiling of early embryogenesis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 2005;434:462–469. doi: 10.1038/nature03353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bartscherer K., Pelte N., Ingelfinger D., Boutros M. Secretion of Wnt ligands requires Evi, a conserved transmembrane protein. Cell. 2006;125:523–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boutros M., Kiger A.A., Armknecht S., Kerr K., Hild M., Koch B., Haas S.A., Consortium H.F., Paro R., Perrimon N. Genome-wide RNAi analysis of growth and viability in Drosophila cells. Science. 2004;303:832–835. doi: 10.1126/science.1091266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiger A.A., Baum B., Jones S., Jones M., Coulson A., Echeverri C., Perrimon N. A functional genomic analysis of cell morphology using RNA interference. J. Biol. 2003;2:27. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kittler R., Putz G., Pelletier L., Poser I., Heninger A.K., Drechsel D., Fischer S., Konstantinova I., Habermann B., Grabner H., et al. An endoribonuclease-prepared siRNA screen in human cells identifies genes essential for cell division. Nature. 2004;432:1036–1040. doi: 10.1038/nature03159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuchs F., Boutros M. Cellular phenotyping by RNAi. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 2006;5:52–56. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/ell007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens J.C., Worby C.A., Simonson-Leff N., Muda M., Maehama T., Hemmings B.A., Dixon J.E. Use of double-stranded RNA interference in Drosophila cell lines to dissect signal transduction pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:6499–6503. doi: 10.1073/pnas.110149597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fire A., Xu S., Montgomery M.K., Kostas S.A., Driver S.E., Mello C.C. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature. 1998;391:806–811. doi: 10.1038/35888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Misra S., Crosby M.A., Mungall C.J., Matthews B.B., Campbell K.S., Hradecky P., Huang Y., Kaminker J.S., Millburn G.H., Prochnik S.E., et al. Annotation of the Drosophila melanogaster euchromatic genome: a systematic review. Genome Biol. 2002;3 doi: 10.1186/gb-2002-3-12-research0083. RESEARCH0083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bier E. Drosophila, the golden bug, emerges as a tool for human genetics. Nature Rev. Genet. 2005;6:9–23. doi: 10.1038/nrg1503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gunsalus K.C., Ge H., Schetter A.J., Goldberg D.S., Han J.D., Hao T., Berriz G.F., Bertin N., Huang J., Chuang L.S., et al. Predictive models of molecular machines involved in Caenorhabditis elegans early embryogenesis. Nature. 2005;436:861–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arziman Z., Horn T., Boutros M. E-RNAi: a web application to design optimized RNAi constructs. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:W582–W588. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hild M., Beckmann B., Haas S., Koch B., Solovyev V., Busold C., Fellenberg K., Boutros M., Vingron M., Sauer F., et al. An integrated gene annotation and transcriptional profiling approach towards the full gene content of the Drosophila genome. Genome Biol. 2003;5:R3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-5-1-r3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foley E., O'Farrell P.H. Functional dissection of an innate immune response by a genome-wide RNAi screen. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:E203. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul S.F., Gish W., Miller W., Myers E.W., Lipman D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Delcher A.L., Phillippy A., Carlton J., Salzberg S.L. Fast algorithms for large-scale genome alignment and comparison. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:2478–2483. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.11.2478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein L.D., Mungall C., Shu S., Caudy M., Mangone M., Day A., Nickerson E., Stajich J.E., Harris T.W., Arva A., et al. The generic genome browser: a building block for a model organism system database. Genome Res. 2002;12:1599–1610. doi: 10.1101/gr.403602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reynolds A., Leake D., Boese Q., Scaringe S., Marshall W.S., Khvorova A. Rational siRNA design for RNA interference. Nat. Biotechnol. 2004;22:326–330. doi: 10.1038/nbt936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drysdale R.A., Crosby M.A., Gelbart W., Campbell K., Emmert D., Matthews B., Russo S., Schroeder A., Smutniak F., Zhang P., et al. FlyBase: genes and gene models. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D390–D395. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma Y., Creanga A., Lum L., Beachy P.A. Prevalence of off-target effects in Drosophila RNA interference screens. Nature. 2006;443:359–363. doi: 10.1038/nature05179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kulkarni M.M., Booker M., Silver S.J., Friedman A., Hong P., Perrimon N., Mathey-Prevot B. Evidence of off-target effects associated with long dsRNAs in Drosophila melanogaster cell-based assays. Nature Methods. 2006;3:833–838. doi: 10.1038/nmeth935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Echeverri C.J., Beachy P.A., Baum B., Boutros M., Buchholz F., Chanda S.K., Downward J., Ellenberg J., Fraser A.G., Hacohen N., et al. Minimizing the risk of reporting false positives in large-scale RNAi screens. Nature Methods. 2006;3:777–779. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1006-777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sims D., Bursteinas B., Gao Q., Zvelebil M., Baum B. FLIGHT: database and tools for the integration and cross-correlation of large-scale RNAi phenotypic datasets. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D479–D483. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Flockhart I., Booker M., Kiger A., Boutros M., Armknecht S., Ramadan N., Richardson K., Xu A., Perrimon N., Mathey-Prevot B. FlyRNAi: the Drosophila RNAi screening center database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D489–D494. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boutros M., Bras L., Huber W. Analysis of cell-based RNAi screens. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R66. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-7-r66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mansmann U., Ruschhaupt M., Huber W. Reproducible statistical analysis in microarray profiling studies. Methods Inf. Med. 2006;45:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]