Abstract

The trigger initiating an autoimmune response against melanocytes in vitiligo remains unclear. Patients frequently experience stress to the skin prior to depigmentation. 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP) was used as a model compound to study the effects of stress on melanocytes. Heat shock protein (HSP)70 generated and secreted in response to 4-TBP was quantified. The protective potential of stress proteins generated following 4-TBP exposure was examined. It was studied whether HSP70 favors dendritic cell (DC) effector functions as well. Melanocytes were more sensitive to 4-TBP than fibroblasts, and HSP70 generated in response to 4-TBP exposure was partially released into the medium by immortalized vitiligo melanocyte cell line PIG3V. Stress protein HSP70 in turn induced membrane tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression and activation of DC effector functions towards stressed melanocytes. Melanocytes exposed to 4-TBP demonstrated elevated TRAIL death receptor expression. DC effector functions were partially inhibited by blocking antibodies to TRAIL. TRAIL expression and infiltration by CD11c + cells was abundant in perilesional vitiligo skin. Stressed melanocytes may mediate DC activation through release of HSP70, and DC effector functions appear to play a previously unappreciated role in progressive vitiligo.

Keywords: autoimmune diseases, skin pigmentation, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

Abbreviations: DC, dendritic cell; FACS, fluorescence activated cell sorting; FaSL, Fas ligand; HSP, heat shock protein; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; JAM, just another method; 4-TBP, 4-tertiary butyl phenol; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

Vitiligo is an acquired skin disorder, involving an autoimmune response against melanocytes (Boissy, 2001; Le Poole et al, 2004). It remains to be explained as to what triggers the autoimmune response to melanocytes. Patients frequently refer to skin trauma as an initiating factor for their disease. Melanocyte overexposure to ultraviolet rays may cause deregulation of melanization and/or of mitosis, inducing a stress response in the pigment cell (Jean et al, 2001). Sites of mechanical stress will express elevated levels of stress proteins (Kippenberger et al, 1999). Burns and cuts have been documented as initiation sites for progressive depigmentation, and the Koebner phenomenon is often observed in vitiligo patients (Le Poole and Boissy, 1997). Finally, in individuals sensitive to bleaching phenols, exposure to phenolic compounds in the workplace can cause what has been coined “occupational vitiligo” (Boissy and Manga, 2004). Skin trauma leads to oxidative stress, and accumulation of H2O2 has been observed in vitiligo lesional skin (Schallreuter et al, 1999). These conditions will induce expression of stress proteins including heat shock protein (HSP)70 and will enhance the activity of anti-oxidative enzymes to protect skin cell viability (Currie and Tanguay, 1991; Calabrese et al, 2001; Renis et al, 2003). In this study, 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP) was chosen as a model compound to address stress protein expression and its involvement in initiating an autoimmune response to melanocytes by dendritic cells (DC).

It has been hypothesized that bleaching compound 4-TBP can serve as an alternative substrate for tyrosinase, which would explain its inhibitory effect on melanin synthesis (Yang and Boissy, 1999). Competitive inhibition of tyrosinase, the rate-limiting enzyme involved in melanogenesis, occurs at low 4-TBP concentrations. Conversion of 4-TBP into semiquinone free radicals can contribute to cellular stress (Boissy and Manga, 2004). Cytotoxic responses occur at a higher concentration of 4-TBP and are independent of the degree of pigmentation of melanocytes (Yang et al, 2000). Expression of the A2b receptor for adenosine was enhanced in response to 4-TBP, and expression of this receptor may sensitize melanocytes to apoptosis (Le Poole et al, 1999).

Stressed cells are characterized by elevated expression of stress proteins. Stress proteins include the HSP family upregulated in response to elevated environmental temperatures and other forms of stress. Stress proteins are evolutionarily very well conserved, and they function as chaperone molecules protecting cellular proteins from premature degradation by supporting proper protein folding (Houry, 2001). Cells with elevated levels of stress proteins are protected from the consequences of subsequent stress episodes (Mestril and Dillmann, 1995).

Contrary to the cytoprotective effect of intracellular stress proteins, once released into the extracellular milieu stress proteins can induce an immune response to the very cells from which they were derived. Stress proteins are immunogenic and were shown to serve as antigens in certain autoimmune diseases, which is best explained by the extensive homology observed between human and bacterial stress proteins or “antigen mimicry” (Bell, 1996; Xu, 2003).

Besides serving as antigens, stress proteins also enhance an immune response by inducing phagocytosis and processing of chaperoned antigens by DC (Noessner et al, 2002). Consequently, stress proteins have been included as adjuvants in tumor vaccines (Srivastava and Amato, 2001).

Recently, it was reported that DC can specifically kill tumor cells whereas surrounding, healthy cells are left untouched (Janjic et al, 2002; Lu et al, 2002). DC-mediated killing was found to be mediated by expression of tumor necrosis factor (TNF) family members on the DC surface, accompanied by the expression of the appropriate receptors by tumor cells (Lu et al, 2002). Healthy control cells do not express the same levels of such receptors, and are thus protected from DC-mediated killing (Lu et al, 2002). The hypothesis under study is that DC are equally capable of killing stressed melanocytes to initiate an autoimmune response resulting in progressive depigmentation of the skin.

The direct effects of 4-TBP exposure on cell viability of control and vitiligo-derived melanocytes was measured. Induction of HSP70 induction was assessed, and expression of HSP70 was artificially elevated by adenoviral overexpression to evaluate its cytoprotective effect. DC exposed to activating stress proteins or activated by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) were reacted with stressed and unstressed melanocytes, and resulting melanocyte death was measured. The cytotoxicity observed was correlated to membrane expression of TNF family members by DC, and to corresponding death receptors on stressed melanocytes. Finally, the results were correlated to observations in vitiligo skin by immunohistology. These studies were performed to evaluate a possible role of stress proteins and of DC in initiating depigmentation.

Results

Viability of cells in the presence and absence of 4-TBP

In Fig 1, the viability of normal melanocyte culture Mc0009 P12, as well as immortalized cell lines PIG1 and PIG3V, and normal fibroblast culture Ff9929 P7 was shown in the presence or absence of 4-TBP. At relatively low concentrations of 4-TBP (250 μM), the viability of both immortalized cell lines, PIG1 and particularly PIG3V, was significantly reduced (to 59.1% and 37.5%, respectively). The difference in viability among PIG1 and PIG3V cells was not considered significant at p = 0.11 in a t test. The viability of primary fibroblast and melanocyte cell cultures was not affected at 250 μM of 4-TBP. Overall, fibroblasts were less sensitive to 4-TBP than melanocytes and a significant reduction in fibroblast viability was noted only at 1 mM of 4-TBP (p = 0.001).

Figure 1. Reduced viability of skin cells in the presence of 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP).

Cultured melanocytes Mc0009 P12, fibroblasts Ff9929 P7, immortalized normal PIG1, and vitiligo PIG3V melanocyte cell lines were subjected to 4-TBP exposure at different concentrations for 72 h. Cell viability ( ± SEM) was measured in a just another method (JAM) assay. At 250 μM of 4-TBP, both immortalized cell lines experienced significantly reduced viability compared with untreated cells (p = 0.013 or 0.009 for PIG1 cells and PIG3V cells, respectively). Representative experiment of three performed.

Induction of HSP70 expression by 4-TBP

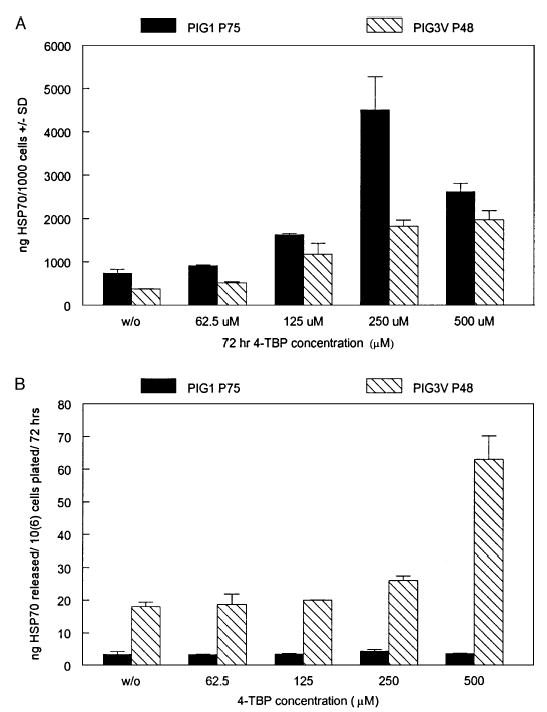

Expression of HSP70 by immortalized melanocytes cultured in the presence or absence of 4-TBP is shown in Fig 2A. It can be observed that the level of intracellular HSP70 increased up to 6.1-fold in PIG1 control melanocytes and 5.2-fold in PIG3V vitiligo melanocytes in the presence of 4-TBP when compared with untreated cells. Interestingly, a 3.3-fold increase in the release of HSP70 was also observed for PIG3V vitiligo melanocytes following treatment with 500 μM 4-TBP as shown in Fig 2B. Moreover, a 5.3-fold increase in the HSP70 content of the medium was noted for PIG3V versus PIG1 melanocytes, further supporting that the vitiligo melanocytes secrete a relatively larger proportion of the stress proteins.

Figure 2. Induction of heat shock protein (HSP)70 expression by 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP).

Immortalized normal control melanocytes PIG1 and vitiligo PIG3V melanocytes were subjected to 4-TBP exposure for 72 h, followed by analysis of (A) intracellular HSP70 expression and (B) HSP70 within the media by ELISA and expressed as HSP70 content ( ± SD). Intracellular expression over untreated control was increased significantly for PIG1 cells at 125 μM of 4-TBP and higher (p = 0.006) and for PIG3V at 62.5 μM and higher (p = 0.016). A significant increase in HSP70 within the media following 4-TBP exposure was noted only for PIG3V cells at 250 (p = 0.030) and 500 μM 4-TBP (p = 0.013).

Protection from 4-TBP exposure by adenoviral overexpression of HSP27 or HSP70

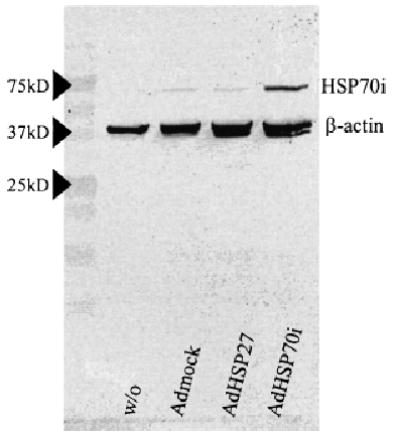

Melanocytes overexpressing HSP27 or HSP70 were treated with 4-TBP in the range of 0–1000 μM for 72 h prior to measuring cell viability. Adenoviral overexpression of HSP70 by melanocytes following adenoviral infection was confirmed by western blotting as shown in Fig 3. A 3.7-fold increase in HSP70 content was demonstrated only for cells exposed to AdHSP70, with no increase observed following exposure to other adenoviruses. Western blot analysis of HSP27 expression revealed that the stress of the adenoviral infection procedure per se upregulated HSP27 expression to a similar extent in all three samples compared with untreated cells (not shown). Similar results were observed for PIG1 cells (not shown). As shown in Fig 4, it was observed that adenoviral overexpression of either HSP27 or HSP70 did not adequately protect the cells from 4-TBP-induced cell death at any of the concentrations tested. The same results were obtained when testing PIG3V, demonstrating that a lack of protection by stress proteins also occurred in vitiligo cells (results not shown).

Figure 3. Adenoviral overexpression of heat shock proteins (HSP).

Overexpression of HSP70i by normal human melanocytes (Mc0009 P13) shown by western blotting following infection with adenovirus, as compared with β-actin content. Relative band intensities support a 3.7-fold increase following adenoviral infection AdHSP70i.

Figure 4. Lack of protection from apoptosis by heat shock proteins (HSP).

Cell viability was measured by trypan blue exclusion of transfected Mc0009 P12 melanocytes following exposure to 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP) for 72 h. Overexpression of either HSP27 or HSP70 did not protect melanocytes from 4-TBP-induced cell death at any of the concentrations tested.

DC-mediated killing of melanocytes

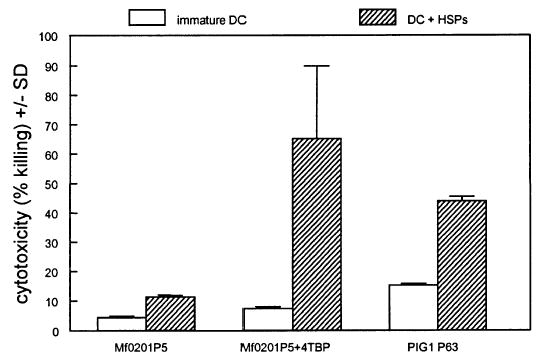

In Fig 5, the cytotoxicity of DC toward normal melanocytes and immortalized PIG1 cells is shown. Normal melanocyte culture Mf0201 P5 was pretreated with or without 250 μM 4-TBP for 24 h. DC were either immature DC or cells activated in the presence of 1 μg per mL of HSP 27, 60, and 70 for 48 h. Pre-treatment of DC with HSP clearly activated the cytotoxic ability of the DC, increasing cell death for both target cell types, most notably for melanocytes exposed to 4-TBP (from 7.4% to 65.2%). Melanocytes cultured in the presence of 4-TBP were sensitized to killing by HSP-activated DC, increasing the cytotoxicity 5.8-fold when chromium release was measured after 48 h compared with cells not treated with the bleaching agent.

Figure 5. Dendritic cell (DC)-mediated killing of stressed melanocytes.

PIG1 immortalized melanocytes or normal melanocytes (Mf0201 P5) pre-treated without or with 250 μM 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP) for 24 h were exposed to immature or heat shock protein-(HSP-) activated DC at an effector:target ratio of 5:1. Cytotoxicity was measured by chromium release at 48 h. DC activated by a cocktail of endotoxin-free HSP 27, 60, and 70 (1 μg per mL for 48 h) were more capable than immature DC of killing 4-TBP-treated melanocyte targets (p = 0.036) and were more effective against 4-TBP-exposed cells than against untreated targets (p = 0.043).

Membrane expression of TNF family molecules and receptors

In Fig 6, upregulation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptors 1 and 2 (TRAILR1 and TRAILR2), and TNF receptors 1 and 2 (TNFR1 and TNFR2) was shown after exposing melanocytes to 4-TBP. The mean fluorescence intensities were increased to 8.5-, 6.3-, 1.8-, and 2.9-fold over untreated cells, respectively, in the presence of 4-TBP, suggesting a potential role in sensitizing melanocytes to DC-mediated killing. Meanwhile, Fas expression was reduced to 0.6-fold at 250 μM 4-TBP. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) histograms also show upregulation of the HSP receptor CD91 (1.7-fold) and more so of tyrosinase-related protein (TRP)-1 (2.2-fold) at 125 μM 4-TBP. Finally, suppression of stem cell factor receptor c-KIT was observed for both 4-TBP concentrations, reducing expression to 0.3-fold at 250 μM 4-TBP.

Figure 6. Melanocyte marker expression modified of 4-tertiary butyl phenol (4-TBP).

Normal melanocytes (Mc0009 P8) were exposed to 0 (Rows 1 and 4), 125 (Rows 2 and 5), or 250 (Rows 3 and 6) μM 4-TBP for 72 h, followed by immunostaining and fluorescence activated cell sorting analysis of expression of tumor necrosis factor-(TNF-) related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor (R)1, TRAILR2, TNFR1, TNFR2, Fas, CD91, tyrosinase-related protein (TRP-1), and c-KIT. Upregulation of TRAIL and TNF receptors as well as CD91 and TRP-1 is accompanied by reduced expression of Fas and c-KIT in response to 4-TBP.

A 2.2-fold increase in the mean fluorescence intensity for TRAIL expression by IFN-γ treated DC was shown in Fig 7. TNF and Fas ligand (FasL) expressions were not upregulated by IFN-γ on the DC membrane. Similar upregulation of TRAIL expression was observed by DC exposed to a cocktail of HSP 27, 60, and 70 (not shown). Histograms representing TRAIL expression in the absence and presence of 4-TBP demonstrate that 4-TBP exposure cannot directly mediate TRAIL upregulation by DC (not shown).

Figure 7. Dendritic cell (DC) tumor necrosis factor- (TNF-) related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression enhanced by interferon-γ (IFN-γ).

Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of DC untreated or activated by exposure to IFN-γ (1000 U per mL for 48 h) revealing enhanced expression of TRAIL, but not Fas or TNF-α. Mean fluorescence intensities ± coefficient of variation (CV) are shown.

Antibody-mediated blocking of TRAIL activity

Melanocytes were exposed to soluble killer TRAIL or to activated DC, in the presence and or absence of TRAIL-reactive antibodies as shown in Fig 8. Killer TRAIL was cytotoxic for up to 37% of PIG1 melanocytes, and this effect was negated in the presence of the anti-TRAIL Ab RIK-2, which restored viability to 95%. More killing of PIG1 cells was observed in the presence of activated DC (53%) than by soluble killer TRAIL, and this response was only partially inhibited by RIK-2, restoring viability to 62%. This suggests that other mechanisms in addition to TRAIL contribute to melanocyte killing by DC.

Figure 8. Killing of immortalized melanocytes by soluble tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL).

Tritium-labeled PIG1 melanocytes were cultured in the presence of 200 ng per mL soluble TRAIL or interferon-γ (IFN-γ) activated dendritic cells (DC) (DCIFN), in the presence or absence of 5 μg per mL blocking antibody to TRAIL (AbTRAIL) for 72 h. Cell viability ( ± SD) was measured. t tests indicated that melanocyte viability was significantly reduced by TRAIL (p = 0.011) and significantly restored by anti-TRAIL antibody (p = 0.018). The viability of PIG1 melanocytes was also significantly reduced in the presence of DC (p = 0.0002). Partial retrieval of melanocyte viability observed for DC-exposed melanocytes incubated in the presence of the blocking Ab to TRAIL was also significant(p= 0.034).

DC infiltration of vitiligo skin

An increase in the number of infiltrating CD11c + DC was observed in perilesional skin (78.03 cells per mm epidermis) when compared with with non-lesional skin from the same patients (37.35 cells per mm epidermis). This difference was found to be significant in a one-tailed paired t test (n = 4; p = 0.026). It should be noted that it was not known whether these patients were exposed to bleaching phenols prior to the onset of their vitiligo. In Figs 9A and B, perilesional skin sections were shown with representative examples of focal infiltration CD11c + and TRAIL + cells, respectively. In Fig 9C, co-detection of CD11c (red) and TRAIL (blue) is depicted. Examples of cells co-expressing both markers are highlighted by purple arrows. These results suggested that TRAIL-expressing DC specifically infiltrate perilesional skin of vitiligo patients with active disease. Expression of TRAILR1 was confined to cells in the basal layer of the epidermis directly adjacent to the border of the lesion. An example of gp100 + melanocytes (blue) expressing TRAILR1 (red) is shown in Fig 9D. Expression was typically observed in a region spanning up to ten melanocytes directly adjacent to the lesion. It is possible that some of the TRAILR1 expression observed should be assigned to interspersing keratinocytes; however, keratinocytes are expected to be less affected by TRAILR1 expression than melanocytes because of their high turnover rate. Expression of TRAILR2 was not observed in vitiligo perilesional skin (not shown).

Figure 9. Support for in vivo involvement of dendritic cell-mediated melanocyte killing in vitiligo.

Immunostaining of perilesional vitiligo skin with antibodies to CD11c (A), tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) (B), or both, with CD11c in red and TRAIL in blue (C), and immuno double staining for melanocyte marker gp100 (blue) and TRAILR1 (red) (D). Results are representative of frozen sections analyzed from four different patients. Purple arrows: examples of double-stained cells. Scale bar = 70 μM (A), 40 μM (B), 20 μM (C), and 40 μM (D).

Discussion

Topically applied phenolic compounds, including 4-TBP, can selectively damage melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis and can lead to progressive skin depigmentation in some individuals. At higher concentrations (>100 μM), 4-TBP is cytotoxic to melanocytes more so than to keratinocytes (Yang et al, 2000). PIG3V vitiligo melanocytes showed a tendency to be more sensitive to 4-TBP than control melanocyte cell line PIG1. The putative cytoprotective effect of stress proteins was inadequate to prevent cell death in either cell line as adenoviral overexpression of either HSP27 or HSP70 failed to protect PIG1 or PIG3V melanocytes from 4-TBP-induced cell death. Such a lack of protection can possibly be explained by inadequate activation of antioxidant enzymes, as supported by the therapeutic potential of pseudocatalase in vitiligo (Schallreuter et al, 1999). Both the PIG1 and PIG3V cell lines upregulated HSP70 expression in response to 4-TBP, and vitiligo melanocytes released a larger proportion of HSP70 into the media. HSP70 released into the medium is likely the result of active secretion by vitiligo melanocytes, as (a) increased release by vitiligo melanocytes over control melanocytes was observed at non-toxic 4-TBP concentrations and (b) HSP70 release was increased by vitiligo melanocytes but not control melanocytes at 500 μM 4-TBP, a concentration that was equally cytotoxic to both cell types. It is of interest that this observation is paralleled by less homogeneous HSP70 immunostaining in perilesional epidermis from three vitiligo patients than in non-lesional skin from the same individuals (not shown), suggesting that release of HSP70 may occur from progressive vitiligo epidermis in vivo.

Release of HSP70 from viable cells was reported for the constitutive as well as the inducible form of HSP70 (Barreto et al, 2003; Broquet et al, 2003). The mechanism reportedly involves the release of membrane-bound HSP70 from lipid rafts (Broquet et al, 2003). For the constitutive form of HSP70, it was demonstrated that release was inducible by a variety of cytokines, most notably IFN-γ (Barreto et al, 2003). The latter cytokine is generated in perilesional vitiligo skin by infiltrating T cells (Le Poole et al, 2003; Wankowicz-Kalinska et al, 2003).

Exposure to 4-TBP enhanced HSP70 expression by melanocytes. Stress proteins occasionally secreted by viable cells have been coined “chaperokines”, reflecting the intercellular effects commonly assigned to cytokines while chaperoning peptides specific to the cell type from which they were derived (Asea et al, 2000; Asea, 2003). This may reflect an early phase of an immune response, as HSP70 was shown to induce secretion of primary cytokines IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α by monocytes/macrophages in a C14-dependent fashion (Asea et al, 2000). It was previously shown that melanocytes can generate primary cytokines as well (Kruger-Krasagakes et al, 1995). As the FACS data shown in Fig 6 support upregulated expression of HSP receptor CD91 by melanocytes in response to 4-TBP, cytokine release from melanocytes may be indirectly increased following 4-TBP exposure.

Following induction of an innate immune response, stress proteins induce antigen-specific immunity by enhancing antigen uptake and processing by DC (Noessner et al, 2002). In this study it was demonstrated that HSP likewise induce DC effector functions. Similarly, HSP70 was shown to enhance natural killer cell cytolytic activity (Multhoff et al, 1999). Results obtained with purified HSP must be considered with some caution as commercial preparations continue to improve in purity, and the effects of HSP on DC activation have been assigned to contaminants (in particular lipopolysaccharide) by others (Bausinger et al, 2002). Commercially obtained purified low-endotoxin HSP used in this study contained <50 EU per mg endotoxin. In accordance with earlier reports, IFN-γ was also shown to activate DC effector functions (Fanger et al, 1999).

Cell surface expression of different TNF family molecules has been implicated in DC effector functions (Lu et al, 2002). Our results indicate that TRAIL is a major player in DC-mediated cytotoxicity toward stressed melanocytes. This is supported by previous reports of a crucial role for TRAIL in DC-mediated killing of tumor cells (Fanger et al, 1999). Here, DC activation was accompanied by enhanced expression of TRAIL, but not of TNF or FasL by DC. Direct exposure to 4-TBP did not induce TRAIL expression by DC (not shown). Exposure of target melanocytes to 4-TBP did induce expression of TRAIL receptors as well as TNF-α receptors, but not Fas. Enhanced receptor expression sensitizes melanocytes to DC-mediated killing, as observed in cytotoxicity assays. TRAIL expressing DC could be replaced at least in part by soluble killer TRAIL, supporting a contribution for TRAIL in melanocyte cytotoxicity. DC-mediated cytotoxicity is commonly thought to be restricted to tumor cells, whereas normal tissue cells remain unaffected. It has been shown, however, that certain preparations of soluble TRAIL are less selective toward malignantly transformed cells (Qin et al, 2001).

Here it was shown, that TRAIL expressing DC can likewise be cytotoxic towards stressed yet untransformed tissue cells. As 4-TBP selectively targets melanocytes, it is likely that 4-TBP-induced epidermal stress can lead to selective killing of epidermal melanocytes by DC. This may instigate a systemic autoimmune response to melanocytes when the same DC return to draining lymph nodes, recruiting melanocyte-reactive cytotoxic T cells to the skin. Our own preliminary data indicate that HSP-treated DC are more efficient at inducing mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) responses than untreated, immature DC (unpublished). The T cell infiltrate resulting from such an interaction may in turn be more effective as stress proteins can ultimately enhance T cell cytotoxicity and induce autoimmunity in vivo (Millar et al, 2003). Taken together, our results indicate that DC-mediated killing of stressed epidermal melanocytes may represent an early and previously unrecognized event contributing to progressive skin depigmentation in vitiligo.

Materials and Methods

Cell culture

Normal human melanocytes were cultured in M154 medium with human melanocyte growth supplements (HMGS; Cascade Biologicals, Portland, Oregon) and with 100 IU per mL penicillin, 100 μg per mL streptomycin, and 250 ng per mL amphotericinB (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, California).

Immortalized human melanocyte cell lines PIG1 (control cell line) and PIG3V (vitiligo cell line) were similarly cultured in M154 with HMGS. These cell lines were immortalized by retroviral introduction of HPV16 E6 and E7 genes (Le Poole et al, 2000).

Normal human dermal fibroblasts were cultured in DMEM with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU per mL penicillin, 100 μg per mL streptomycin, and 250 ng per mL amphotericinB (Invitrogen).

Human adherent monocyte-derived DC were generated from leukapheresed peripheral blood mononuclear cells, and cultured in AIMV medium (Invitrogen) in the presence of 25 ng per mL IL-4 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota) and 100 ng per mL granulocyte macrophage-colony stimulating factor (Immunex, Seattle, Washington) for 7 d. DC were activated in the presence of 1 μg per mL HSP27, HSP60, and HSP70 each (Stressgen, Victoria, British Columbia, Canada) or 1000 U per mL of human IFN-γ (R&D Systems) for the last 48 h of culture.

Viability testing

Cultured cells were treated with 4-TBP in concentrations ranging from 0 to 1000 μM for 72 h. The viability of the resulting cell cultures was assessed by trypan blue exclusion, and expressed as a percentage of the total number of cells observed. Alternatively, cells were plated at 10,000 cells per well of a 96-well plate, labeled with 1 μCi per well of 3H-thymidine (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, New Jersey), and treated in the presence and absence of 4-TBP for 72 h. The plates were then harvested in a Packard Filtermate 196-cell harvester (Minneapolis, Minnesota) and tritium incorporated in the DNA of viable cells was counted in a Packard Top Count microplate scintillation and luminescence counter.

HSP70 detection

Western blotting to assess the levels of stress proteins was performed by denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of cell homogenates in a 10% gel, and subsequent indirect immunostaining of the resulting gel blot by anti-human HSP70i antibody SPA-810 (Stressgen Biotechnologies, San Diego, California) as well as by C4 anti-actin antibody (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohio), followed by alkaline phosphatase-labeled IgG1-specific antibodies. Antibodies were diluted according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Alkaline phosphatase activity was revealed with 0.15 g per mL 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate and 0.3 mg per mL nitro blue tetrazolium (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri).

ELISA testing was used to accurately quantify the amount of HSP70 generated and secreted by melanocytes and fibroblasts in response to 4-TBP exposure. ELISA kits were purchased from Stressgen to measure HSP70 content of cell homogenates and conditioned cell supernatants according to the manufacturer’ instructions. Briefly, experimental samples or different protein concentrations of recombinant HSP70 were added to wells of a 96-well plate pre-coated with a monoclonal antibody to inducible HSP70. After removal of the samples, the washed plate was incubated with biotinylated polyclonal antibody to inducible HSP70 followed by peroxidase-conjugated avidin, and tetramethylbenzidine was used as a substrate for peroxidase. Peroxidase activity was measured at 450 nm in an EL312E microplate reader (Bio-Tech Instruments, Winooski, Vermont). HSP70 content of individual samples was calculated from the HSP70 standard curve.

Cytoprotection following adenoviral HSP overexpression

Cells were incubated with 107 pfu of adenovirus encoding HSP27, HSP70, or neither (mock virus) per 106 melanocytes in 2% FBS in M154 for 2 h at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The adenovirus-containing medium was removed and replaced with M154 and HMGS, and cells were left to express the adenoviral genes for 48 h prior to testing. Overexpression of HSP by this treatment was assessed by western blotting as described above. The cytoprotective effect of stress protein overexpression was measured by viability assays following 3 d of 4-TBP exposure by counting the percentage of trypan blue-excluding cells.

Cytotoxicity assessment

For quantitative measurements of DC cytotoxicity, just another method (JAM) assays were used (Matzinger, 1991). Briefly, target cells were pre-labeled with 3H-thymidine at 1 μCi per 10,000 cells for 16 h. Immature or activated DC were added to target cells, and DC-mediated cytotoxicity was measured 72 h after adding DC to the labeled target cells by comparing radioactivity retained by viable cells among individual sample wells. In some experiments, cytotoxicity was measured following exposure of target cells to apoptosis-inducing molecules. Alternatively, target cells were labeled with 5 μCi/well of 51Cr (sodium chromate) (Amersham Biotechnologies, Quebec, Canada), and cytotoxicity was measured as γ radiation released into the supernatant by dying cells. The latter method was replaced by JAM assays where long incubation times led to high background counts as a result of spontaneous chromium release.

Expression of TNF family molecules and their receptors

Expression of TNF, TRAIL, and FasL on the cell surface of adherent monocyte-derived human DC was assessed by FACS analysis. Similarly, FACS staining was used to probe target melanocytes for expression of TNFR1 and TNFR2, TRAILR1 and TRAILR2 and decoy receptors 3 and 4, and Fas. Primary antibodies reactive with human antigens include M-301 to TNF (Endogen, Woburn, Massachusetts), rabbit polyclonal antiserum to TRAIL (Calbiochem, San Diego, California), NOK-1 mouse monoclonal antibody to FasL (Caltag, Burlingame, California), MAB225 mouse monoclonal antibody to TNFR1 (R&D Systems), MAB226 mouse monoclonal antibody to TNFR2 (R&D Systems), mouse monoclonal antibody 32A1380 to TRAILR1 (Imgenex, San Diego, California), mouse monoclonal antibody 54B1005 to TRAILR2 (Imgenex), rabbit polyclonal antiserum to TRAILR3 (Orbigen, San Diego, California), goat polyclonal antiserum to TRAILR4 (R&D Systems), and MAB142 mouse monoclonal antibody to Fas (R&D Systems) at empirically determined concentrations within the range provided by the manufacturer. Membrane expression was assessed by indirect immunostaining of scraped cells, using biotinylated species-specific secondary Abs and phycoerythrin-labeled streptavidin as a fluorescent label. The mean fluorescence intensities and percentage of stained cells among at least 5000 cells were measured by a FACSCalibur benchtop flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, California) equipped with a 15 mW argon–ion laser for detection of fluorescence plus right and forward angle scatter, using CellQuest software to control data acquisition.

TRAIL-mediated killing of immortalized melanocytes

PIG1 cells were plated at 10,000 cells per well in a 96-well plate, labeled with 3H-thymidine at 1 μCi/well for 16 h, and subsequently exposed to recombinant human soluble killer TRAIL (AxxoraLLC, San Diego, California) at 200 ng per mL, RIK-2 antibody to TRAIL (eBioScience, San Diego, California) at 5 μg per mL, and DC activated by IFN-γ pre-treatment (1000 U per mL for 48 h), or combinations thereof. Cell viability was measured after 72 h as described under “cytotoxicity assessment”.

Immunohistology of DC in vitiligo

Four millimeter biopsies were obtained from non-lesional and perilesional skin of four patients with progressive vitiligo. Participants gave their written informed consent; the study was conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki principles and the Institutional Review Board of Loyola University Medical Center approved all described studies. The abundance of DC among the skin samples was assessed by immunohistology. Frozen sections fixed in cold acetone were exposed to primary antibodies MAB1971 to CD11c (Chemicon, Temecula, California) and 4C4.9 to S100 (Cell Marque Corporation, Austin, Texas) reactive with human DC. The number of CD11c + per mm of epidermal length was quantified in three skin sections from each biopsy. The presence or absence of melanocytes was confirmed using antibodies NKI-Beteb to human gp100 (Caltag) and M2-9E3 to human MART-1 (NeoMarkers, Fremont, California). Expression of TNF, TRAIL, and FasL as well as its receptors was assessed using antibodies described above under FACS analysis except for MAB687 to human TRAIL (R&D Systems). Single and double stainings were completed as previously described (Le Poole et al, 1996). Briefly, in single immunostainings, incubation with the primary antibody was followed up with biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse antiserum (Dakopatts, Glostrup, Denmark) and peroxidase-labeled streptavidin (Dakopatts) diluted according to the manufacturers’ recommendations. In double stainings, enzyme-labeled isotype-specific secondary antibodies (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, Alabama) were combined to react with the primary antibodies of interest. Alkaline phosphatase activity was detected using Fast Blue BB (Sigma) as a substrate, and AEC (Sigma) was used as the substrate for peroxidase.

Statistical analysis

t Tests were used for a posteriori comparisons among experimental results to control values. Sample sizes for each comparison are as indicated in the figure legends.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 63rd Annual Meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology and at the 11th Annual Meeting of the Pan American Society for Pigment Cell Research.

The study was carried out at Department of Pathology/Oncology Institute, Loyola University, Chicago, Illinois, USA.

Support for these investigations was provided by NIH/NIAMS grant RO3-AR050137-01 (to CLP), R01-AR46115 (to REB), NCI PO-1 CA59327 (to BJN), and NIH/NHLBI HL067971 & HL61339 (to RM).

References

- Asea A. Chaperokine-induced signal transduction pathways. Exerc Immunol Rev. 2003;9:25–33. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asea A, Kabingu E, Stevenson MA, Calderwood SK. HSP70 peptide bearing and peptide-negative preparations act as chaperokines. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2000;5:425–431. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2000)005<0425:hpbapn>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barreto A, Gonzalez JM, Kabingu E, Asea A, Fiorentino S. Stress-induced release of HSC70 from human tumors. Cell Immunol. 2003;222:97–104. doi: 10.1016/s0008-8749(03)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bausinger H, Lipsker D, Ziylan U, et al. Endotoxin-free heat shock protein 70 fails to induce APC activation. Eur J Immunol. 2002;32:3708–3713. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3708::AID-IMMU3708>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CG. Do stress proteins have a regulatory role in autoimmune rheumatoid arthritis? Biochem Soc Trans. 1996;24:494S. doi: 10.1042/bst024494s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissy RE. Vitiligo. In: Theofilopoulos AN, Bona CA, editors. The Molecular Pathology of Autoimmunity. 2nd edn. Langhorne, PA: Gordon and Breach/Harwood Academic Publishers; 2001. pp. 773–780. [Google Scholar]

- Boissy RE, Manga P. On the etiology of contact/occupational vitiligo. Pigment Cell Res. 2004;17:208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00130.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broquet AH, Thomas G, Masliah J, Trugnan G, Bachelet M. Expression of the molecular chaperone Hsp70 in detergent-resistant microdomains correlates with its membrane delivery and release. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21601–21606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302326200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese V, Sapagnini G, Catalano C, Bates TE, Geraci D, Pennisi G, Giuffrida Stella AM. Regulation of heat shock protein synthesis in human skin fibroblasts in response to oxidative stress: Role of vitamin E. Int J Tissue React. 2001;23:127–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie RW, Tanguay RM. Analysis of RNA from transcripts for catalase and SP71 in rat hearts after in vivo hyperthermia. Biochem Cell Biol. 1991;69:375–382. doi: 10.1139/o91-057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanger NA, Maliszewski CR, Schooley K, Griffith TS. Human dendritic cells mediate cellular apoptosis via tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand (TRAIL) J Exp Med. 1999;190:1155–1164. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.8.1155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houry WA. Chaperone-assisted protein folding in the cell cytoplasm. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2001;2:227–244. doi: 10.2174/1389203013381134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janjic BM, Lu G, Pimenov A, Whiteside TL, Storkus WJ, Vujanovic NL. Innate direct anticancer effector function of human immature dendritic cells. I Involvement of an apoptosis-inducing pathway. J Immunol. 2002;168:1823–1830. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jean S, Bideau C, Bellon L, et al. TH expression of genes induced in melanocytes by exposure to 365-nm UVA: Study by cDNA arrays and real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2001;1522:89–96. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4781(01)00326-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kippenberger S, Bernd A, Loitsch S, Muller J, Guschel M, Kaufmann R. Cyclic stretch up-regulates proliferation and heat shock protein 90 expression in human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 1999;12:246–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1999.tb00757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger-Krasagakes S, Krasagakis K, Garbe C, Diamantstein T. Production of cytokines by human melanoma cells and melanocytes. Recent Results Cancer Res. 1995;139:155–168. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-78771-3_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole C, Boissy RE. Vitiligo. Seminar Cutan Med Surg. 1997;16:3–14. doi: 10.1016/s1085-5629(97)80030-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole IC, Boissy RE, Sarangarajan R, et al. PIG3V, an immortalized human vitiligo melanocyte cell line, expresses dilated rough endoplasmic reticulum. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim. 2000;36:309–319. doi: 10.1290/1071-2690(2000)036<0309:PAIHVM>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole IC, Stennett LS, Bonish BK, et al. Expansion of vitiligo lesions is associated with reduced epidermal CDw60 expression and increased expression of HLA-DR in perilesional skin. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149:739–748. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05539.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole IC, van den Wijngaard RMJGJ, Westerhof W, Das PK. Presence of T cells and macrophages in inflammatory vitiligo skin parallels melanocyte disappearance. Am J Pathol. 1996;148:1219–1228. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole IC, Wankowicz-Kalinska A, van den Wijngaard RMJGJ, Nickoloff BJ, Das PK. Autoimmune aspects of depigmentation in vitiligo. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2004;9:68–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1087-0024.2004.00825.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Poole IC, Yang F, Brown TL, Cornelius J, Babcock GF, Das PK, Boissy RE. Altered gene expression in melanocytes exposed to 4-tertiary butylphenol (4-TBP): Upregulation of the A2B receptor for adenosine. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:725–731. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G, Janjic BM, Janjic J, Whiteside TL, Storkus WJ, Vujanovic NL. Innate direct anticancer effector function of human dendritic cells. II Role of TNF, lymphotoxin-alpha(1)beta(2), Fas ligand and TNF-related apoptosis inducing ligand. J Immunol. 2002;168:1831–1839. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matzinger P. The JAM test. A simple assay for DNA fragmentation and cell death. J Immunol Methods. 1991;145:185–192. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90325-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mestril R, Dillmann WH. Heat shock proteins and protection against myocardial ischemia. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1995;27:45–52. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2828(08)80006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millar DG, Garza KM, Odermatt B, Elford A, Ono N, Li Z, Ohashi PS. Hsp70 promotes antigen-presenting cell function and converts tolerance to autoimmunity in vivo. Nat Med. 2003;9:1469–1476. doi: 10.1038/nm962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multhoff G, Mizzen L, Winchester CC, et al. Heat shock protein 70 (Hsp70) stimulates proliferation and cytolytic activity of natural killer cells. Exp Hematol. 1999;27:1627–1636. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(99)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noessner E, Gastpar R, Milani V, et al. Tumor-derived heat shock protein 70 peptide complexes are cross-presented by human dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:5424–5432. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.10.5424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J, Chaturvedi V, Bonish B, Nickoloff BJ. Avoiding premature apoptosis of normal epidermal cells. Nat Med. 2001;7:385–386. doi: 10.1038/86401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renis M, Cardille V, Grasso S, Palumbo M, Scifo C. Switching off HSP70 and INOS to study their role in normal and H2O2-stressed human fibroblasts. Life Sci. 2003;26:757–769. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schallreuter KU, Moore J, Wood JM, et al. In vivo and in vitro evidence for hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulation in the epidermis of patients with vitiligo and its successful removal by a UVB-activated pseudocatalase. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 1999;4:91–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsp.5640189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava PK, Amato RJ. Heat shock proteins: The ‘Swiss army knife’ vaccines against cancer and infectious agents. Vaccine. 2001;19:2590–2597. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(00)00492-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wankowicz-Kalinska A, van den Wijngaard RM, Tigges BJ, et al. Immunopolarization of CD4 + and CD8 + T cells to type-1 like is associated with melanocyte loss in human vitiligo. Lab Invest. 2003;83:683–695. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000069521.42488.1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q. Infections, heat shock proteins and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2003;18:245–252. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200307000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Boissy RE. Effects of 4-tertiairy butylphenol on the tyrosinase activity in human melanocytes. Pigment Cell Res. 1999;12:237–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0749.1999.tb00756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Sarangarajan R, Le Poole IC, Medrano EE, Boissy RE. The cytotoxicity and apoptosis induced by 4-tertiary butylphenol in human melanocytes are independent of tyrosinase activity. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;114:157–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00836.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]