Abstract

Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) at membrane microdomains plays an essential role in the growth control of epidermal cells, including cancer cells derived therefrom. Ligand-dependent activation of EGFR tyrosine kinase is known to be inhibited by ganglioside GM3, but to a much lesser degree by other glycosphingolipids. However, the mechanism of the inhibitory effect of GM3 on EGFR tyrosine kinase has been ambiguous. The mechanism is now defined by binding of N-linked glycan having multiple GlcNAc termini to GM3 through carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction, based on the following data: (i) EGFR (molecular mass, ≈170 kDa) has N-linked glycan with GlcNAc termini, as probed by mAb (J1) or lectin (GS-II); (ii) GS-II-bound EGFR also bound to anti-EGFR Ab as well as to GM3-coated beads; (iii) GM3 inhibitory effect on EGFR tyrosine kinase was abrogated in vitro by coincubation with glycan having multiple GlcNAc termini and in cell culture in situ incubated with the same glycan; and (iv) cells treated with swainsonine, which increased expression of complex-type and hybrid-type glycans with GlcNAc termini, displayed higher inhibition of EGFR kinase by GM3 than swainsonine-untreated control cells. A similar effect was observed with 1-deoxymannojirimycin, which increased hybrid-type structure in addition to major accumulation of high mannose-type glycan. These findings indicate that N-linked glycan with GlcNAc termini linked to EGFR is the target to interact with GM3, causing inhibition of EGF-induced EGFR tyrosine kinase.

Keywords: carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction, N-linked glycan, glycosphingolipid, ganglioside, oligosaccharide Fr.B

Glycosphingolipids (GSLs), particularly ganglioside GM3, were initially found to induce refractoriness of fibroblast growth to fibroblast growth factor (FGF) in a chemically defined medium. GM3 was found to inhibit FGF internalization due to a change in FGF receptor function (1). This concept was extended to the inhibitory effects of GM3 and other gangliosides on tyrosine kinases in platelet-derived growth factor receptor (2, 3) and in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) (4). Since then, there have been many studies on the modulatory effects of various GSLs and sphingolipids on various types of receptors (refs. 5–7; see also Discussion).

The inhibitory effect of GM3 on EGFR tyrosine kinase is the best-studied example (8–12). For this effect, N-glycosylation of EGFR may be required (11) because N-glycosylation, particularly at domains 3 and 4, may induce conformational modification leading to receptor dimerization (12). The concept of receptor dimerization has been well accepted to explain ligand-induced receptor activation (13). Nevertheless, the mechanism by which GM3 interacts with EGFR and modulates its function is unknown. The present study addresses a specific type of N-glycosylation of the receptor, its role in receptor interaction with microenvironmental GM3, and how GM3 and N-glycosylation cooperatively regulate EGFR function. A few previous lines of investigation indicate that GM3 interacts with various carbohydrates, such as those with GalNAcβ 1–4Galβ 1–4Glc (14–17), with Galβ 1–4Glc (18, 19), with lactosylsphingosine (20), or with N-linked glycan having multivalent GlcNAc termini (21). We therefore studied the correlation between GM3 interaction and EGFR-associated N-linked glycan. We present evidence that interaction of GM3 with an N-linked glycan having multiple GlcNAc, i.e., specific carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction, controls signal transduction through EGFR function and receptor-associated tyrosine kinase activity.

Results

Presence of GlcNAc Termini in N-Linked Glycan of EGFR in A431 Cells, as Indicated by Multiple Western Blot Analyses.

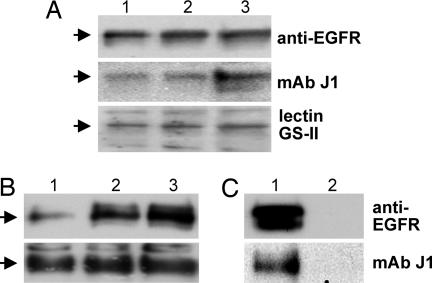

A major single band with a molecular mass of ≈170 kDa was stained by Western blot of A431 cell lysate using anti-EGFR IgG mAb, mAb J1 (22), or lectin from Griffonia simplicifolia (GS-II) (23). Both J1 and GS-II are directed to nonsubstituted GlcNAc termini of glycan. The intensity of band stained by these reagents was proportional to the amount of protein of the cell lysate applied for Western blot analysis (Fig. 1A). An identical band with molecular mass ≈170 kDa was detected when A431 cell lysate was precipitated with GS-II conjugated to agarose followed by Western blot with anti-EGFR and mAb J1 (Fig. 1B). Bands detected by Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb in Fig. 1 A and B were not due to contaminating mouse IgG (Fig. 1C). None of the control glycoproteins, fetuin (10 μg), transferrin (10 μg), or ovalbumin (12.5 μg), gave an ≈170-kDa band showing reactivity with anti-EGFR mAb, lectin GS-II, or mAb J1; control ovalbumin gave a major GS-II-stained ≈45-kDa band (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

EGFR of A431 cells expresses glycan(s) with terminal GlcNAc structure, probed by mAb J1 and by lectin GS-II. A431 cells were grown, harvested, pelleted, and lysed in RIPA buffer, and lysate was subjected to Western blot analysis as described in Materials and Methods. (A) EGFR band (≈170-kDa molecular mass) blotted by anti-EGFR mAb, mAb J1, and HRP-labeled GS-II lectin. Protein of cell lysate [25 μg (lane 1), 50 μg (lane 2), or 100 μg (lane 3)] was analyzed by Western blot with the respective Abs and lectin as indicated on the right. (B) GS-II/agarose binding moiety of lysate, Western blotted by anti-EGFR mAb and mAb J1. We washed 25 μl (lane 1), 50 μl (lane 2), and 100 μl (lane 3) of GS-II/agarose beads (4–5 mg of GS-II per milliliter of beads) twice with ice-cold PBS and incubated them with A431 cell lysate (0.5 mg of protein) in PBS containing 0.9 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM MnCl2 with tumbling for 1 h at 4°C. After centrifugation at 1,410 × g for 5 min at 4°C, the beads were washed three times with 1 ml of PBS containing 0.9 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM MnCl2, followed by centrifugation at 1,410 × g for 5 min. The bound fraction was released by boiling in SDS/PAGE sample buffer and analyzed by Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb and with mAb J1. (C) Absence of mouse IgG in A431 cell lysate. Because EGFR was probed by anti-human EGFR mouse IgG mAb, the possible presence of mouse IgG in original A431 cell lysate should be ruled out. For this purpose, A431 cell lysate (500 μg of protein) was precleared with 25 μl of protein A/G-agarose beads for 2 h at 4°C and centrifuged at 980 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was incubated with 4 μg of anti-EGFR (lane 1) or 4 μg of mouse IgG (lane 2) as a control overnight at 4°C. The supernatant was then added to 25 μl of protein A/G-agarose, tumbled for 2 h at 4°C, and centrifuged at 980 × g for 5 min at 4°C. The beads were washed twice with 1 ml of RIPA buffer, and the samples were prepared as above for SDS/PAGE and Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb and mAb J1. Note that immunoprecipitate by anti-EGFR (lane 1) but not by mouse IgG (lane 2) showed reactivity with anti-EGFR and J1. Arrows on the left indicate ≈170 kDa based on the positions of molecular mass markers.

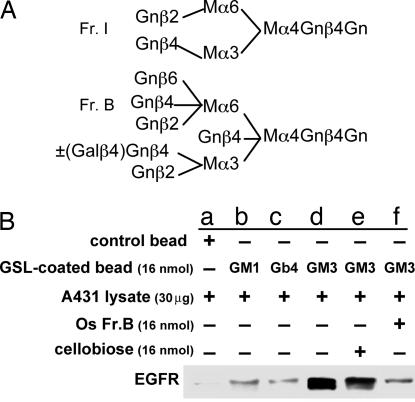

Interaction of GM3 and Other GSLs with EGFR, and Inhibition of This Interaction by Os Fr.B.

We showed previously (21) that GM3 binds strongly to an N-linked glycan with five to six GlcNAc termini [termed oligosaccharide (Os) Fr.B] and binds weakly to N-linked glycan with two GlcNAc termini (termed Os Fr.I). These structures are shown in Fig. 2A. Similar structures with GlcNAc termini are assumed to be present in EGFR N-linked glycan, as probed by GS-II and mAb J1 (Fig. 1 A and B). We therefore investigated whether EGFR binds selectively to GM3 rather than other GSLs and whether Os Fr.B can abrogate such binding. We studied binding of polystyrene beads (1 μm in diameter; 6.85 × 107 beads) coated with GM3, GM1, or Gb4 to EGFR, analyzed by Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb (see Fig. 2B legend). EGFR showed strong binding to beads coated with GM3 (Fig. 2B, lane d), weak binding to beads coated with GM1 or Gb4 (lanes b and c), and no binding to control beads (lane a). The GM3 to EGFR binding was not affected by coincubation with cellobiose (lane e) but was strongly inhibited by coincubation with Os Fr.B (lane f).

Fig. 2.

Binding of GM3 and other GSLs to EGFR and inhibition of this binding by Os Fr.B. (A) Isolation and characterization of structure (see ref. 21). Structure of Os Fr.I and Os Fr.B. Os Fr.B is a mixture of structures with and without Galβ4 substitution to a defined N-acetylglucosamine (Gn) as shown. M, mannose. (B) Interaction of GSL-coated polystyrene beads with EGFR and inhibition of this interaction by Os Fr.B. GM3, GM1, or Gb4 (16 nmol each) was dried, dissolved in 1 ml of an ethanol/water solution (9:1), mixed with 6.85 × 107 polystyrene beads [1 μm in diameter (Interfacial Dynamics, Portland, OR), previously washed in PBS, and suspended in ethanol], and incubated with tumbling for 1 h at room temperature. After being washed three times with 0.5 ml of PBS, the beads were incubated with 300 μl of 0.1% gelatin for 1 h with tumbling at room temperature to block nonspecific binding sites, centrifuged at 1,410 × g for 5 min, washed with TBS, and resuspended in 500 μl of TBS(+) [130 mM NaCl/10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 8.0) containing 0.9 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM MnCl2] containing A431 cell lysate (30 μg of protein). The mixture was kept overnight at 4°C with tumbling and then washed three times with TBS(+). Protein bound to GSL-coated beads was solubilized by boiling in SDS/PAGE sample buffer as above and analyzed by Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb. For effects of OS Fr.B, OS Fr.I, or cellobiose on binding of EGFR to GM3-coated beads, beads were resuspended in 500 μl of TBS(+) containing A431 cell lysate and 16 nmol of Os Fr.B (molecular weight, 2,211.3), 16 nmol of Os Fr.I (molecular weight, 1,317.4), or 16 nmol of cellobiose (molecular weight, 342.3). For a control, GSL-noncoated beads were incubated with A431 cell lysate in the absence of Os or cellobiose. EGFR bands in the Western blots in each lane are as follows. a, beads alone; b, beads coated with GM1; c, beads coated with Gb4; d, beads coated with GM3; e, beads coated with GM3 and incubated with cellobiose; f, beads coated with GM3 and incubated with Os Fr.B. Beads coated with GM3 and incubated with Os Fr.I showed reduced adsorption of EGFR, as in our previous study (ref. 21 and data not shown).

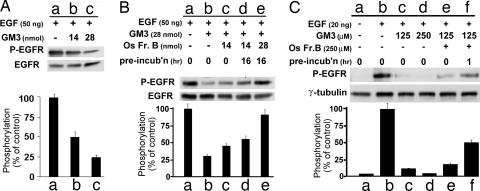

Os Fr.B Blocks GM3-Induced Inhibition of EGFR Tyrosine Phosphorylation in Vitro and in Situ.

EGFR tyrosine kinase activity induced by 50 ng of EGF [phosphorylated EGFR (P-EGFR)] in A431 cell membrane fraction was greatly reduced (to ≈20% or ≈50% of control level, respectively) by addition of 14 or 28 nmol of GM3 (Fig. 3A). The density of the P-EGFR bands (degree of phosphorylation) in Fig. 3A Upper as a percentage of the GM3-omitted control is shown as a bar graph in Fig. 3A Lower and is based on Scion image densitometry.

Fig. 3.

Inhibitory effect of GM3 on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation and its abrogation by Os Fr.B. (A) In vitro inhibitory effect of GM3 on P-EGFR. GM3 (14 and 28 nmol) in a 2:1 chloroform/methanol solution was dried under a nitrogen stream, dissolved in 30 μl of 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) by vigorous vortex mixing and sonication for 10 min, added to a 5-μl A431 cell membrane fraction (30 μg of protein), and incubated for 15 min at 22°C. After addition of 5 μl (50 ng) of EGF in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 22°C then further incubated on ice for 10 min. Phosphorylation was analyzed by Western blot with mAb PY20, and the same blot was reblotted by using anti-EGFR mAb as described in Materials and Methods. The density of the bands was analyzed as described in Materials and Methods, and the P-EGFR level was calculated as the density with PY20 divided by the density with anti-EGFR and is shown as the percentage of control value (without GM3) in Lower. Values are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (B) Os Fr.B abrogates an in vitro GM3 inhibitory effect on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation. GM3 (28 nmol) was dried and dissolved in 16 μl of 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) containing 2.5 mM MnCl2, 25 μM ZnCl2, 2.5 mM CaCl2, and 125 μM Na3VO4, as described above. Os Fr.B (14 and 28 nmol) in 14 μl of 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4) was added to the GM3 suspension and preincubated at 37°C for the indicated time. A 5-μl A431 cell membrane fraction (30 μg of protein) was added to the preincubated mixture and incubated for 15 min at 22°C. After addition of 5 μl of 10 μg/ml EGF in 20 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 22°C then incubated on ice for 10 min. P-EGFR was analyzed and calculated as shown in A. Values are shown as mean ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) In situ abrogating effect of Os Fr.B on the GM3 inhibitory effect on EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation in A431 cells. GM3 in a 2:1 chloroform/methanol solution was dried as above and dissolved in ethanol, dried again, and sonicated in serum-free DMEM for 10 min. Os Fr.B was dissolved in serum-free DMEM and preincubated with GM3 prepared as above at 37°C before use. A431 cells (1 × 105) were cultured in 12-well plates in DMEM containing 5% FCS for 24 h at 37°C, starved in 200 μl of serum-free DMEM for 24 h, washed three times with serum-free DMEM, and incubated with GM3, Os Fr.B, and a mixture of GM3 and Os Fr.B in 200 μl of serum-free DMEM for 24 h. Final concentrations of GM3 and Os Fr.B were 125 or 250 μM and 250 μM, respectively. Cells were washed three times with serum-free DMEM, and 200 μl of 100 ng/ml EGF in serum-free DMEM was added and incubated for 2 h at 37°C. Cells were washed five times with cold PBS and lysed in 200 μl of RIPA buffer. Protein (2 μg) was subjected to Western blot with mAb PY20, and membranes were reblotted with anti-γ-tubulin as a loading control. Results shown are representative of four independent experiments.

Under the same conditions of EGF (50 ng) and GM3 level (28 nmol), P-EGFR in the A431 cell membrane fraction was ≈25–30% of the control level (without GM3) (Fig. 3B, lane b). The inhibitory effect of GM3 was reduced in the presence of Os Fr.B (14 nmol) (lane c), further reduced after 16 h of incubation with the same amount of Os Fr.B (lane d), and almost completely abrogated (i.e., returned to control level without GM3) when GM3 was incubated with 28 nmol of Os Fr.B for 16 h (lane e).

A similar abrogating effect of Os Fr.B on GM3-dependent inhibition of P-EGFR was observed in cultured A431 cells, but concentrations of EGF, GM3, and Os Fr.B were different from the in vitro effect shown in Fig. 3 A and B. Cells in culture were stimulated with 20 ng of EGF (200 μl of 100 ng/ml EGF). The P-EGFR level was strongly enhanced (Fig. 3C, lane b) by this stimulation compared with control without EGF (lane a). Incubation with 125 and 250 μM GM3 strongly inhibited P-EGFR induced by 25 ng of EGF (lanes c and d), whereas addition of 250 μM Os Fr.B to 125 μM GM3 without preincubation slightly increased P-EGFR level (lane e), and the same incubation mixture with 1 h of preincubation significantly increased P-EGFR level (lane f). No significant effect was observed for Os Fr.I or cellobiose (data not shown).

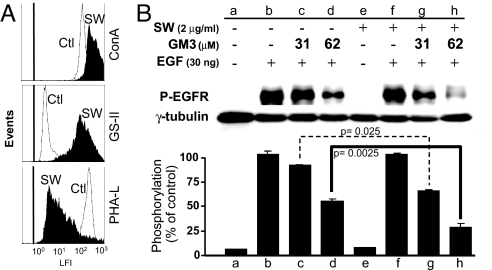

Effect of N-Glycosylation Modification in A431 Cells on GM3-Dependent Inhibition of EGF-Induced P-EGFR.

To confirm that the inhibitory effect of GM3 on EGF-induced P-EGFR is due to interaction of N-linked glycan of EGFR having GlcNAc termini with GM3 surrounding the receptor, the effect of modification of N-linked glycan processing (24) was examined. Swainsonine (SW), which inhibits α-mannosidase-II, caused accumulation of hybrid-type (25) having GlcNAc termini with a high level of GS-II binding sites (Fig. 4A) and enhanced the GM3-dependent inhibitory effect on EGF-induced EGFR kinase activity in situ using cells in culture (Fig. 4B). Addition of GM3, at a 31 or 62 μM concentration, showed greater inhibition of P-EGFR in SW-treated cells compared with control cells. The inhibitory effect of SW was significant in cells added with 62 μM GM3 (Fig. 4B, lane and bar h vs. d; P < 0.0025).

Fig. 4.

Effect of N-glycosylation processing inhibition on GM3-dependent EGFR kinase activity in A431 cells. A431 cells (1 × 105) were cultured in 12-well plates in DMEM containing 5% FCS at 37°C until reaching ≈30% confluency. The cells were then cultured with 1.0 ml of fresh medium containing 2 μg of glycosylation-processing inhibitor SW (which inhibits α-mannosidase-II) at 37°C for 24 h and further incubated with 1.0 ml of serum-free DMEM containing 2 μg of SW at 37°C for 24 h. Cells were subjected to flow cytometric analysis or to inhibition of EGFR phosphorylation by GM3. SW-treated cells showed no difference in morphology or viability compared with nontreated cells. (A) Flow cytometric analysis of SW-treated A431 cells was performed as described (25) using three types of probes: ConA-FITC (Top), GS-II-FITC (Middle), and Phaseolus vulgaris lectin-l (PHA-L)-FITC (Bottom). The vertical line on the left shows the peak position of control cells without lectin staining. (B) Effect of SW treatment on GM3 inhibition. Control and SW-treated A431 cells were preincubated with 31 and 62 μM GM3 and stimulated with EGF. EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation was measured, analyzed, and shown as described in Fig. 3C. γ-Tubulin was used as a loading control. The intensity of the band was determined by densitometry using Scion image program. Values are shown as means ± SD from three independent experiments. The significance of each difference is indicated as a P value.

1-Deoxymannojirimycin (1-DMJ), which inhibits α-mannosidase-I, caused accumulation of N-linked high-mannose type, and to a lesser extent, of hybrid-type having GlcNAc termini (25). Treatment with 1-DMJ also enhanced GM3-dependent inhibition of EGF-induced EGFR kinase (data not shown). Treatment with inhibitor did not show any significant toxic effect as assessed by morphology and by viability using trypan blue exclusion test.

Discussion

Growth factor receptors are characterized by common susceptibility to various types of gangliosides and GSLs that modulate specific tyrosine kinases associated with the receptors (5–7). We initially observed that addition of GM3 in chemically defined medium for fibroblasts inhibited internalization of FGF together with its receptor (1). At that time, the concept of tyrosine kinase associated with FGFR was not established. Recent studies on GM3 effect on FGFR indicate the occurrence of specific interaction of GM3 with FGFR at glycosynaptic microdomain, particularly in the presence of tetraspanins CD9 and CD81 in WI38 cells, which show clear contact inhibition of cell growth (26). In contrast, ganglioside GM1 promotes tyrosine phosphorylation of nerve growth factor receptor (Trk A) in PC12 cells (27). NeuAcnLc4 strongly inhibits insulin receptor kinase in insulin-sensitive human cell lines IM9, HL60, and K562 (28). In contrast, insulin receptor of mouse cell lines is susceptible to GM3 (29).

Essentially all GSLs and gangliosides in membrane are organized with cytoplasmic signal transducers, tetraspanins, and various growth factor receptors and integrins to form microdomains that control glycosylation-dependent cell adhesion, motility, and growth, termed “glycosynapse” (30, 31).

GM3 has been known since 1986 to inhibit EGFR tyrosine kinase (4, 8). However, the mechanism for this inhibitory process has been ambiguous. Results of the present study show that GM3 inhibits EGFR tyrosine kinase through binding to N-linked glycan having multivalent GlcNAc termini on EGFR. For example, (i) EGFR in A431 cells has N-linked glycan with GlcNAc termini, as probed by mAb J1 or lectin GS-II (Fig. 1). (ii) EGFR bound preferentially to GM3-coated polystyrene beads, and the binding was inhibited by Os Fr.B having GlcNAc termini (Fig. 2). (iii) GM3 inhibited EGFR tyrosine phosphorylation in dose-dependent fashion, and the inhibition was blocked by Os Fr.B in vitro and in situ (Fig. 3). (iv) Inhibitors of glycosylation processing such as SW or 1-DMJ cause an increased level of hybrid-type with GlcNAc termini, and the inhibitory effect of GM3 on tyrosine kinase is increased accordingly (Fig. 4). It is important to note that GM3 susceptibility of EGFR is highly dependent on the presence of N-glycosylation, because tunicamycin treatment abolishes GM3 susceptibility (11). The importance of N-glycosylation and ganglioside composition in defining integrin function is also well documented (25, 32–35). The effect of gangliosides GT1b and GD3 on α5β1 integrin in keratinocytes was ascribed to interaction of N-linked glycan (high-mannose type has been claimed) of α5 with ganglioside (34). Results of the present study are based on a different glycosylation system with different receptors in different types of cells but indicate a similar relationship, i.e., that GM3 to N-linked glycan interaction is the basic mechanism by which GM3 binds to a specific site in EGFR. This mechanism is essentially a form of carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction (CCI) within the same membrane plane and presumably within the same glycosynaptic microdomain.

Previous studies on CCI deal with cell-to-cell interaction, i.e., trans-CCI, which mediates homotypic recognition of interfacing embryonal carcinoma cells based on Lex-to-Lex interaction (36–39) or of interfacing sponge cells based on species-specific interaction of Os clusters (40, 41). Trans-CCI that mediates heterotypic recognition between GM3-expressing cells and Gg3-expressing cells has been studied in detail (14–17). In contrast, the present study deals with occurrence of CCI within the same cell membrane, possibly within the same microdomain, i.e., cis-CCI. The cis-CCI process may provide an important basis for glycosylation-dependent control of signal transduction leading to a series of phenotypic changes.

Materials and Methods

Os, GM3, Abs, and Other Reagents.

Two Os preparations, Os Fr.I and Os Fr.B, with multiple terminal GlcNAc, were purified from a ConA-nonbinding fraction of N-linked glycan of chicken ovalbumin (grade V), and their structures were determined by a 2D mapping technique of pyridylaminated (PA)-Os derivatives (42), by comparison with HPLC data of ≈500 reference PA-Os in a homemade Web application (www.glycoanalysis.info) (43). PA-Os derivatives were prepared based on the original procedure (44). GM3 and Gb4 were prepared in this laboratory from dog and human erythrocytes, respectively. GM1 was a gift from Sandro Sonnino (University of Milan, Milan, Italy).

Mouse IgG1 anti-EGFR mAb (clone F4, directed to the C-terminal domain) and control mouse IgG were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Control mouse IgM (TEPC 183), goat anti-mouse IgM, and mouse anti-γ-tubulin mAb were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). mAb anti-phospho-Tyr (PY20) was from BD Transduction (Franklin Lakes, NJ). mAb (mouse IgM) directed to GlcNAc termini of glycoproteins or GSLs was prepared from hybridoma J1 (22). Goat anti-mouse IgM-HRP and goat anti-mouse IgG-HRP were from Southern Biotech (Birmingham, AL). Lectins Phageolus vulgaris lectin-l-FITC, GS-II-HRP, GS-II-FITC, and GS-II/agarose (4–5 mg of GS-II per milliliter of beads) were from EY Laboratories (San Mateo, CA).

1-DMJ was from EMD Biosciences (La Jolla, CA). Recombinant human EGF was from Earth Chemical Co. (Tokyo, Japan). Protein concentration was determined with MicroBCA kit from Pierce (Rockford, IL) by using BSA as a standard. Solvents (HPLC grade) were from Fisher Scientific (Hampton, NH). Other reagents were from Sigma unless described otherwise.

Detection of Terminal GlcNAc Structure on EGFR.

Human epidermoid carcinoma A431 cells were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and cultured in DMEM with 10% FCS (HyClone, Logan, UT) as described (4), with the addition of 100 units/ml penicillin and 10 μg/ml streptomycin. To prepare whole-cell lysate, a cell pellet collected with a rubber scraper was washed with PBS, lysed with RIPA buffer (1% Triton X-100/0.1% SDS/0.5% sodium deoxycholic acid/5 mM tetrasodium pyrophosphate/50 mM sodium fluoride/1 mM Na3VO4/5 mM EDTA/150 mM NaCl/20 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/2 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride/0.076 trypsin inhibitor unit/ml aprotinin), and centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 10 min. Terminal GlcNAc on EGFR was assessed as follows: (i) Cell lysate was analyzed by Western blot with mAb J1 and by lectin blot with GS-II, as described below. (ii) Cell lysate was mixed with GS-II/agarose, and the bound fraction was analyzed by Western blot with anti-EGFR mAb and with mAb J1. For details of the procedure, see the Fig. 1B legend. (iii) Cell lysate was mixed with anti-EGFR mAb, and immunoprecipitate collected with protein A/G-agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) was analyzed by Western blot with mAb J1.

SDS/PAGE, Western Blot, and Lectin Blot.

All samples were prepared in SDS/PAGE sample buffer containing 5% 2-mercaptoethanol and boiled for 5 min. Proteins were separated on 8% gels, transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, Billerica, MA), and blotted with mAbs as described (34) by using a Supersignal chemiluminescence substrate kit (Pierce). For GS-II lectin blot, PVDF membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in TBS (140 mM NaCl/10 mM Tris·HCl, pH 8.0) for 1 h at room temperature, washed five times with TBS containing 0.9 mM CaCl2, 0.5 mM MgSO4, and 0.1 mM MnCl2 [TBS(+)], and incubated overnight at 4°C with 20 μg/ml GS-II-HRP in TBS(+). The membrane was washed gently five times with TBS(+) and incubated with a substrate kit as above.

For reprobing the same blots with more than one Ab, the blot was briefly rinsed with distilled water and then incubated with stripping buffer (2% SDS/62.6 mM Tris·HCl, pH 6.7/0.78% 2-mercaptoethanol) for 20 min at 60°C. After rinsing five times with TBS/0.05% of Tween 20 for 5 min each, the PVDF membrane was subjected to blocking procedure. All procedures after blocking were as described above. The intensity of bands was determined by densitometric analysis using a Scion imaging program.

Inhibitory Effect of GM3 on EGF-Induced P-EGFR Activity and Its Abrogation with Os Fr.B.

EGFR tyrosine kinase activity was assessed by EGFR autophosphorylation. For the in vitro assay, the cell membrane fraction from A431 cells was prepared and analyzed as described (4, 9), except that tyrosine phosphorylation was determined with mAb PY20 rather than 32P incorporation from γ-ATP. To assess the effect of Os Fr.B, GM3 and Os Fr.B were preincubated at 37°C for the indicated time (Fig. 3B) and added to the EGF-stimulated P-EGFR assay using the membrane fraction. The effect of Os Fr.B was further confirmed with A431 cells in situ. Preincubated mixture of GM3 and Os Fr.B was added to a monolayer of A431 cells and incubated for 24 h. After being washed, the cells were stimulated with EGF and then lysed with RIPA buffer for SDS/PAGE and Western blot to measure EGFR autophosphorylation.

Effect of N-Glycosylation Processing Modification.

A431 cells in a monolayer were pretreated with 2 μg/ml SW or 1 mM 1-DMJ for 48 h and observed by microscopy to evaluate the possible toxic effect. After detaching the cells with 1 mM EDTA/PBS, changes to the cell surface glycan profile were analyzed by staining with ConA-FITC, GS-II-FITC, and Phageolus vulgaris lectin-l-FITC as described (25), followed by flow cytometry (Beckman Coulter, Miami, FL). To evaluate the inhibitory effect of GM3 in cells treated with glycosylation inhibitors, pretreated monolayer cells were treated with GM3, and EGF-induced EGFR autophosphorylation was analyzed as above.

Acknowledgments

We thank Profs. Soledad Penades (Instituto de Investigaciones Quimicas, Seville, Spain) and Kazukiyo Kobayashi (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan) for comments on the manuscript.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- CCI

carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction

- 1-DMJ

1-deoxymannojirimycin

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- GS-II

Griffonia simplicifolia-II lectin

- GSL

glycosphingolipid

- Os

oligosaccharide

- P-EGFR

phosphorylated EGFR

- SW

swainsonine.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bremer EG, Hakomori S. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1982;106:711–718. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(82)91769-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bremer EG, Hakomori S, Bowen-Pope DF, Raines EW, Ross R. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:6818–6825. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yates AJ, VanBrocklyn J, Saqr HE, Guan Z, Stokes BT, O'Dorisio MS. Exp Cell Res. 1993;204:38–45. doi: 10.1006/excr.1993.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bremer EG, Schlessinger J, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1986;261:2434–2440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hakomori S, Igarashi Y. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1995;118:1091–1103. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miljan EA, Bremer EG. Science STKE. 2002;15:1–10. doi: 10.1126/stke.2002.160.re15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yates AJ, Rampersaud A. In: Sphingolipids as Signaling Modulators in the Nervous System. Ledeen RW, Hakomori S, Yates AJ, Schneider JS, Yu RK, editors. Vol 845. New York: New York Acad Sci; 1998. pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanai N, Nores GA, MacLeod C, Torres-Mendez C-R, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:10915–10921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhou Q, Hakomori S, Kitamura K, Igarashi Y. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1959–1965. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miljan EA, Meuillet EJ, Mania-Farnell B, George D, Yamamoto H, Simon HG, Bremer EG. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:10108–10113. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111669200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang X-Q, Sun P, O'Gorman M, Tai T, Paller AS. Glycobiology. 2001;11:515–522. doi: 10.1093/glycob/11.7.515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fernandes H, Cohen S, Bishayee S. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:5375–5383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005599200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ullrich A, Schlessinger J. Cell. 1990;61:203–212. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90801-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kojima N, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20159–20162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuura K, Kitakouji H, Tsuchida A, Sawada N, Ishida H, Kiso M, Kobayashi K. Chem Letters. 1998;27:1293–1294. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matsuura K, Kitakouji H, Sawada N, Ishida H, Kiso M, Kitajima K, Kobayashi K. J Am Chem Soc. 2000;122:7406–7407. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuura K, Kobayashi K. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:139–148. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000044845.64354.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kojima N, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:17552–17558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rojo J, Diaz V, de la Fuente JM, Segura I, Barrientos AG, Riese HH, Bernad A, Penades S. Chembiochem. 2004;5:291–297. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200300726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Santacroce PV, Basu A. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2003;42:95–98. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon S, Nakayama K, Takahashi N, Yagi H, Utkina N, Wang HY, Kato K, Sadilek M, Hakomori S. Glycoconj J. 2006 Nov 18; doi: 10.1007/s10719-006-9001-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Symington FW, Fenderson BA, Hakomori S. Mol Immunol. 1984;21:877–882. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(84)90142-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lyer PN, Wilkinson KD, Goldstein LJ. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1976;177:330–333. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(76)90444-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kornfeld R, Kornfeld S. In: The Biochemistry of Glycoproteins and Proteoglycans. Lennarz WJ, editor. New York: Plenum; 1980. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang Y, Zhao JH, Zhang XY, Guo HB, Liu F, Chen HL. Mol Cell Biochem. 2004;260:137–146. doi: 10.1023/b:mcbi.0000026065.84798.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Toledo MS, Suzuki E, Handa K, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34655–34664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M403857200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mutoh T, Tokuda A, Miyada T, Hamaguchi M, Fujiki N. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:5087–5091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.5087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nojiri H, Stroud MR, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:4531–4537. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tagami S, Inokuchi J, Kabayama K, Yoshimura H, Kitamura F, Uemura S, Ogawa C, Ishii A, Saito M, Ohtsuka Y, et al. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3085–3092. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103705200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hakomori S, Handa K. FEBS Lett. 2002;531:88–92. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hakomori S. Ann Braz Acad Sci. 2004;76:553–572. doi: 10.1590/s0001-37652004000300010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zheng M, Fang H, Tsuruoka T, Tsuji T, Sasaki T, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2217–2222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zheng M, Fang H, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:12325–12331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X, Sun P, Al-Qamari A, Tai T, Kawashima I, Paller AS. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8436–8444. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M006097200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gu J, Taniguchi N. Glycoconj J. 2004;21:9–15. doi: 10.1023/B:GLYC.0000043741.47559.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eggens I, Fenderson BA, Toyokuni T, Dean B, Stroud MR, Hakomori S. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:9476–9484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de la Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Rojas TC, Rojo J, Canada J, Fernandez A, Penades S. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2001;40:2259–2261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tromas C, Rojo J, de la Fuente JM, Barrientos AG, Garcia R, Penades S. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2001;40:3052–3055. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010817)40:16<3052::AID-ANIE3052>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gourier C, Pincet F, Perez E, Zhang Y, Zhu Z, Mallet JM, Sinay P. Angew Chem Intl Ed. 2005;44:1683–1687. doi: 10.1002/anie.200461224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haseley SR, Vermeer HJ, Kamerling JP, Vliegenthart JFG. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9419–9424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151111298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bucior I, Scheuring S, Engel A, Burger MM. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:529–537. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tomiya N, Awaya J, Kurono M, Endo S, Arata Y, Takahashi N. Anal Biochem. 1988;171:73–90. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi N, Kato K. Trends Glycosci Glycotechnol. 2003;15:235–251. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hase S, Ibuki T, Ikenaka T. J Biochem (Tokyo) 1984;95:197–203. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]