Abstract

Otx2 is a paired type homeobox gene that plays essential roles in each step and site of head development in vertebrates. In the mouse, Otx2 expression in the anterior neuroectoderm is regulated primarily by two distinct enhancers: anterior neuroectoderm (AN) and forebrain/midbrain (FM) enhancers at 92 kb and 75 kb 5′of the Otx2 locus, respectively. The AN enhancer has activity in the entire anterior neuroectoderm at headfold and early somite stages, whereas the FM enhancer is subsequently active in the future caudal forebrain and midbrain ectoderm. In tetrapods, both AN and FM enhancers are conserved, whereas the AN region is missing in teleosts, despite overt Otx2 expression in the anterior neuroectoderm. Here, we show that zebrafish and fugu FM regions drive expression not only in the forebrain and midbrain but also in the anterior neuroectoderm at headfold stage. The analysis of coelacanth and skate genomic Otx2 orthologues suggests that the utilization of the two enhancers, AN and FM, is an ancestral condition. In contrast, the AN enhancer has been specifically lost in the teleost lineage with a compensatory establishment of AN activity within the FM enhancer. Furthermore, the AN activity in the fish FM enhancer was established by recruiting upstream factors different from those that direct the tetrapod AN enhancer, yet zebrafish FM enhancer is active in both mouse and zebrafish anterior neuroectoderm at the headfold stage.

Keywords: anterior neuroectoderm, coelacanth, enhancer, tetrapod, chondrichthyes

The vertebrate head is an evolutionary novelty called “new head” by Gans and Northcutt (1) that is characterized by structures that derive from the anterior neuroectoderm cells, cephalic neural crest cells, and placode cells. It is also a structure that has most dramatically changed during vertebrate evolution. Diversity in the animal body plan might have been brought about by changes in expression of a relatively limited number of key developmental regulators such as Hox genes in the trunk (2, 3). The Otx family of genes plays essential roles in head development (4–9). Otx genes encode a paired-type of homeoprotein homologous to a Drosophila head gap gene, otd. Gnathostomes possess three paralogues, Otx1, Otx2, and Otx5, whereas teleosts that underwent genome duplication could possess extra copies. In mouse, Otx2 plays major roles in each site of head development (5–11): epiblast, anterior visceral endoderm, anterior mesendoderm, anterior neuroectoderm, forebrain/midbrain, and cephalic neural crest cells. Fugu has two Otx2, but zebrafish has only one (9).

To elucidate the molecular mechanisms regulating Otx2 expression during mouse brain development, we have identified three enhancers: anterior neuroectoderm enhancer (AN), forebrain/midbrain enhancer (FM), and forebrain/midbrain enhancer 2 (FM2) at 90 kb and 75 kb upstream and 115 kb downstream of the Otx2 translational start site, respectively (8, 9). The AN enhancer is not active in the epiblast but becomes active at embryonic day (E) 7.0 in the entire anterior neuroectoderm. However, the AN activity is lost by E8.5, and subsequent Otx2 expression in the anterior neuroectoderm is regulated by FM and FM2 enhancers. The latter are not active in the ectoderm at headfold stage when the AN enhancer is active. FM and FM2 enhancers also do not have activity in the most rostral part of forebrain that corresponds to the future telencephalon and hypothalamus. In the mutant, Otx2ΔAN/−, which lacks the AN enhancer, the entire anterior neuroectoderm is unable to be maintained and is caudalized into Gbx2-positive metencephalon; the Emx2-positive telencephalon is not formed (8). The Otx2 expression under FM and FM2 enhancers overlaps with Otx1 expression, and, in the compound mutant that lacks the FM and FM2 enhancers and Otx1, Otx1−/−Otx2ΔFMΔFM2/ΔFMΔFM2 (Y. Sakurai, D.K., and S.A., unpublished data; and ref. 9), the anterior neuroectoderm is normally developing at E8.5, but the caudal forebrain and midbrain are subsequently caudalized into Gbx2-positive metencephalon; the mutant, however, develops Emx2-positive telencephalon where Otx1 or FM or FM2 enhancer has no activity.

Genomic homology searches and close sequence analysis have revealed that the AN enhancer is conserved among tetrapods (9). However, the enhancer has not been found in teleost fishes including zebrafish, fugu, and medaka. In contrast, the FM enhancer is conserved in both tetrapods and teleosts. The FM2 enhancer is unique to rodent and is not present in other mammals or vertebrates. We have been interested in the phylogenetic origins and the functional consequences of differences in Otx2 enhancer organization in brain development among vertebrates.

In this study, we first show that in zebrafish and fugu (which has no AN enhancer) the FM enhancer has the activity not only in the forebrain and midbrain at the pharyngeal stage but also in the anterior neuroectoderm at the headfold and early somite stages. Second, we show that this AN activity in zebrafish FM enhancer is apparently established with upstream factors that are different from those of tetrapod AN enhancers; however, these factors are present in mouse anterior neuroectoderm at headfold stage. Third, we analyzed the extended Otx2 genomic sequences of two outgroup species (clearnose skate, Raja eglanteria, and Indonesian coelacanth, Latimeria menadoensis) and infer that the ancestral gnathostome deployed two enhancers, AN and FM, for regulating brain development. Our findings suggest that the AN enhancer was specifically lost in the teleost lineage with the acquisition of AN activity by the FM enhancer.

Results

Enhancer Activities of Mouse and Zebrafish FM Regions in Mouse Embryos.

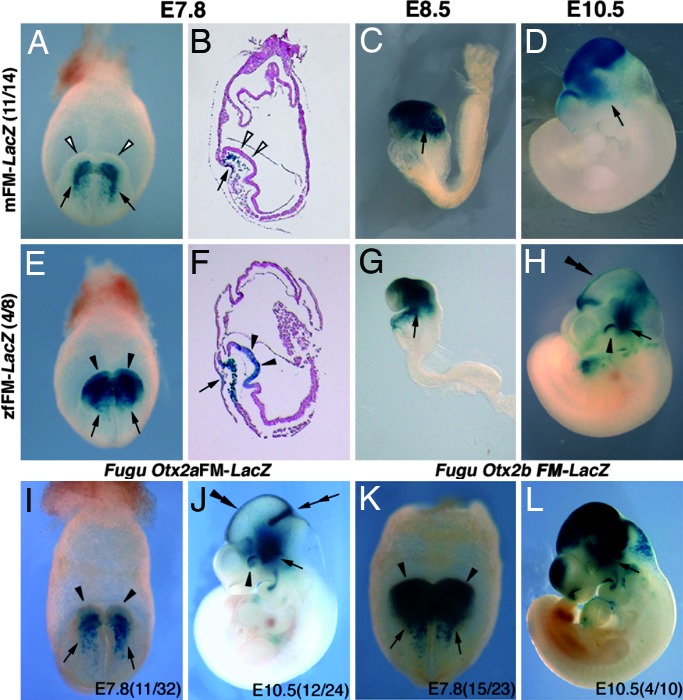

To test whether the FM region in zebrafish (zfFM) has the same enhancer activity as mouse FM (mFM) enhancer, transgenic mouse lines were established with zfFM-lacZ and mFM-lacZ constructs. Throughout this study the enhancer analysis with transgenic mouse embryos was conducted by using the 1.8-kb mouse Otx2 promoter region (8). The 1.8-kb region harbors enhancer activities in the anterior visceral endoderm, anterior mesoendoderm, and cephalic mesenchyme cells; these activities serve as a positive control for proper transgene integration and are indicated by arrows in each figure.

The mFM enhancer activity takes place around E8.5 in the anterior neuroectoderm; it lacks the activity in the most rostral part that corresponds to the future telencephalon and hypothalamus (Fig. 1C). The zfFM region exhibited the same activity at this stage (Fig. 1G). At subsequent stages, the activity of the mFM enhancer covers caudal forebrain (archencephalon and diencephalon) and midbrain with the sharp caudal boundary at the midbrain/hindbrain junction (Fig. 1D). In contrast, the activity of the zfFM region was intense in thalamus and caudal midbrain, whereas it was weak in the pretectum and anterior midbrain excepting their roof area (Fig. 1H). Moreover, unexpectedly, the zfFM region had the enhancer activity for the expression in the anterior neuroectoderm at headfold stage (Fig. 1 E and F). The mFM enhancer does not have this activity when the mouse AN enhancer is active (Fig. 1 A and B). The AN activity of the FM enhancer was also tested with Fugu Otx2a and Otx2b genes (Fig. 4A) by transient transgenic assay at E7.8 and E10.5 (Fig. 1 I–L). The FM region of the Fugu Otx2b gene (fbFM) exhibited the activity not only in mouse forebrain and midbrain at E10.5 (Fig. 1L), but also in mouse anterior neuroectoderm at E7.8 (Fig. 1K). The activity of the FM region of the Fugu Otx2a gene (faFM) was weakly found in anterior neuroectoderm at E7.8 (Fig. 1I); in E10.5 forebrain and midbrain it was observed in the roof area and isthmus (Fig. 1J). In mouse Otx2 genome, the AN enhancer, but not the FM enhancer, has an activity in eyes (Fig. 1D) (8); the zfFM and faFM, but not fbFM, also exhibited an activity in mouse eyes (Fig. 1 H and J).

Fig. 1.

Activity pattern of FM regions in mouse Otx2 (A–D), zebrafish Otx2 (E–H), Fugu Otx2a (I and J), and Fugu Otx2b (K and L) genes during mouse anterior neuroectoderm development. Permanent transgenic lines were established to detect mouse and zebrafish FM activities; numbers of βGal-positive mouse lines among transgenic lines established with mouse 1.8-kb promoter are indicated in the parentheses at left (A–H). FM activities of Fugu Otx2a and Otx2b genes were determined by transient transgenic assay; numbers of β-gal-positive embryos among transgenic embryos are indicated in parenthesis of each panel (I–L). Fugu Otx2b genome is diverged (Fig. 3A, Fig. 4, and SI Fig. 7B); however, it has a comparable ORF, and its transcription was confirmed in Takifugu niphobles (data not shown). (A, E, I, and K) frontal views, (B and F) sagittal views, and (C, D, G, H, J, and L) lateral views (anterior is toward the left). Arrows indicate the expression because of the activity of the promoter region in anterior mesendoderm (A, B, E, F, I, and K) and cephalic mesenchyme (C, D, G, H, J, and L). Open arrowheads in A and B indicate the absence and solid arrowheads in (E, F, I, and K) the presence of anterior neuroectoderm expression; in I the activity in anterior neuroectoderm is weak, but present. Solid arrowheads and double arrowheads in H and J indicate the expression in eyes and in the roof, respectively. A double arrow in J indicates the activity in isthmic region.

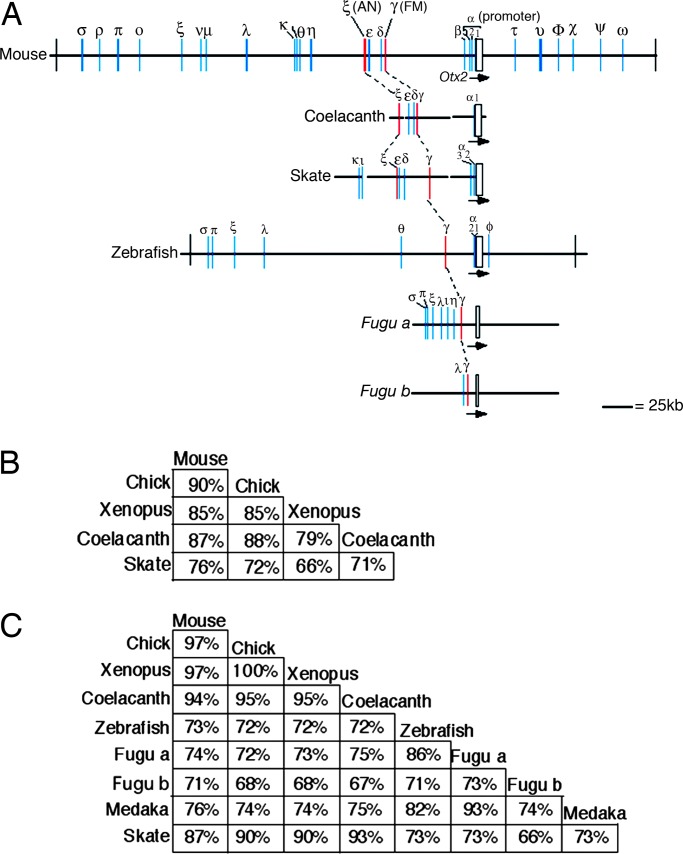

Fig. 4.

Genome structures and conservation of ReOtx2 and LmOtx2 loci. (A) Schematic representation of conserved domains. The 24 domains well conserved among mouse, human, chick, and Xenopus are indicated (blue and red bars). With the addendum of more genome information the conserved domains have been renumbered from our previous report (9). White box and arrows indicate the coding regions and direction of transcription, respectively. Black bars at ends indicate the location of the coding regions of the adjacent genes. In the promoter region there are three subdomains, α1, α2, and α3, conserved among tetrapods. Mouse Otx2 has three transcriptional start sites (39), and α1–α3 corresponds to these sites. Enhancers for the Otx2 expression in mouse visceral endoderm, anterior mesendoderm and cephalic mesenchyme exist around the α1 subdomain (40, 41). It is conserved well in coelacanth and zebrafish Otx2 loci and weakly in skate Otx2 and Fugu Otx2b loci but not in Fugu Otx2a locus. (B and C) Percent match of nucleotide identity in the 90-bp AN (B) and 100-bp FM (C) core regions among animals indicated.

Enhancer Activities of Mouse and Zebrafish FM Regions in Zebrafish Embryos.

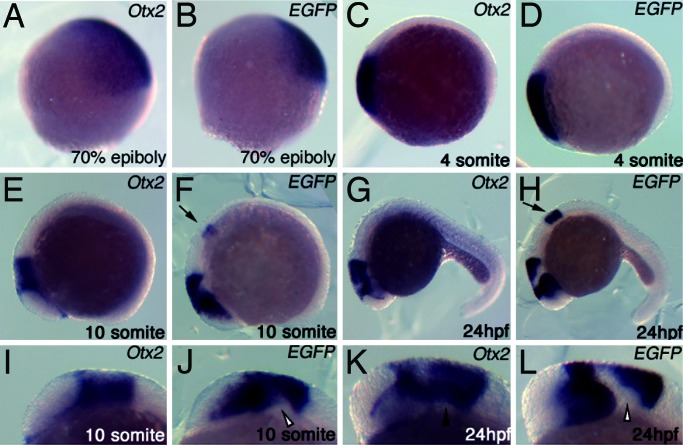

To examine how the activity of the zfFM region covers the endogenous Otx2 expression, the analysis was conducted in zebrafish embryos with zebrafish Otx2 promoter. Four stable transgenic lines were established whose embryos displayed an almost identical pattern of marker (EGFP) expression. The zfFM region exhibited the activity in the zebrafish anterior neuroectoderm at 60–70% epiboly stage and early somite stage; the activity was indistinguishable from the endogenous Otx2 expression at these stages (Fig. 2A–D). By the 10-somite stage the endogenous Otx2 expression is lost in the most rostral part that corresponds to the future telencephalon and hypothalamus; the expression also became weak in pretectum and anterior tectum areas (Fig. 2 E and I). So was the activity of the zfFM region (Fig. 2 F and J). However, several discrepancies were apparent at this stage between the endogenous Otx2 expression and the zfFM activity. The zfFM activity was absent in a portion of the tegmentum (open arrowhead in Fig. 2J). In addition, an ectopic activity was present in myelencephalon that corresponds to rhombomere 5 and 6 (arrow in Fig. 2F). These discrepancies were more apparent at 24 h after fertilization (hpf) (Fig. 2 G, H, K, and L). This zfFM activity in 24 hpf zebrafish brain may largely correspond to the zfFM activity in E10.5 mouse brain (Fig. 1H), although the ectopic activity in the myelencephalon was never observed in the mouse brain.

Fig. 2.

Activity pattern of zebrafish FM enhancer during zebrafish anterior neuroectoderm development. EGFP mRNA expression driven by zfFM in a typical permanent transgenic zebrafish line (B, D, F, H, J, and L) is compared with endogenous Otx2 mRNA expression (A, C, E, G, I, and K). All images are lateral views. (I–L) are views of head region in (E–H) at high magnification. Arrows in F and H indicate ectopic expression in hindbrain. A solid arrowhead in K indicates the presence of the endogenous Otx2 expression and open arrowheads in J and L indicate the absence of the transgenic EGFP expression in tegmentum.

We also attempted to determine the mFM activity in zebrafish embryos by using zebrafish Otx2 promoter. Unfortunately, however, no permanent transgenic fish lines could be established even after >100 founders were screened. Consequently, the mFM activity was determined by transient transgenic assay [results are summarized in supporting information (SI) Fig. 6 and SI Table 1]. The assay, although it has an inherent problem of mosaicism in transgene integration, has suggested that, as in mouse, mouse FM enhancer is inactive at headfold stage, but active at 6-somite and 20-hpf stages in zebrafish. The mosaicism precludes the precise identification of the negative region, but mFM was apparently inactive in the most rostral part (SI Fig. 6 D–F) as it was in the mouse anterior neuroectoderm (Fig. 1C). The mFM activity pattern in zebrafish may be largely the same as its activity pattern in mouse embryos; in contrast to zfFM, it appears to have the activity in the pretectum and anterior tectum. However, mFM obviously has the activity in zebrafish eyes (arrowheads in SI Fig. 6E); it is mouse AN and not mFM that drives Otx2 activity in mouse eyes (8, 9).

Core Sequences in FM Enhancer.

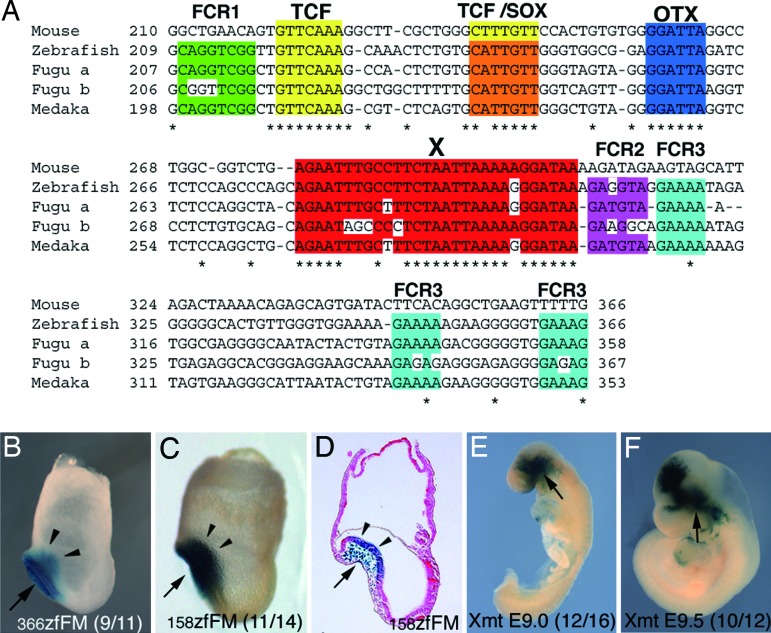

Zebrafish FM, but not tetrapod FM, exhibits activity in the anterior neuroectoderm at the headfold and early somite stages. Which sequences are responsible for this difference? In tetrapod FM regions, sequences are well conserved >366 bp (9). In the 600 bp zfFM used in Figs. 1 and 2, this 5′ 366-bp region (366zfFM) was sufficient for the AN activity (Fig. 3B); the 3′ 234-bp sequence of the 600-bp zfFM did not have the AN activity (data not shown). The mouse AN enhancer was narrowed down to a 90-bp sequence (90AN) (8), and the sequence was 85% identical between mouse and Xenopus (Fig. 4B and SI Fig. 7A). There is no sequence that is conserved over more than five nucleotides between the teleost 366FM and tetrapod 90AN but is absent in tetrapod 366FM.

Fig. 3.

Core sequences in FM enhancer. (A) Sequence comparison in the 3′ half of the FM 366-bp region among mouse and teleosts. The region is highly conserved among tetrapods (9). Asterisks indicate nucleotides identical among all these animals. Colored boxes indicate conserved sites; the sequence is well conserved in the 100-bp sequence from TCF site to X site (Fig. 4C and SI Fig. 7A). (B–D) The role of the 5′ 366 bp (B) of the zebrafish 600-bp FM enhancer and of the 3′ 158 bp (C and D) of the 366-bp enhancer in the activity in mouse anterior neuroectoderm at E7.75. (E and F) The role of the X site of mouse FM enhancer in its activity in mouse anterior neuroectoderm at E9.0 (E) and E9.5 (F); the 29-bp X site is replaced with the BglII linker. Solid arrowheads in B–D indicate the presence of the β-gal expression in anterior neuroectoderm. Activities were determined by transient transgenic assay. See Fig. 1 legends for arrows in B–F. B–F are lateral views (anterior is toward the left).

In the 5′ half of the 366FM region, sequences are scarcely conserved not only between tetrapods and teleosts but also among teleosts; sequences are moderately conserved in the 3′ half (Fig. 3A). Indeed the 3′ half of zebrafish 366FM (158zfFM) was sufficient to confer the AN activity (Fig. 3 C and D). The 3′ half has several potential transcription factor-binding sites. One TCF site is conserved in both tetrapods and teleosts, another TCF site in tetrapods is converted into a Sox site in teleosts by a single nucleotide change, and an OTX site is also conserved in all animals (Fig. 3A). We previously demonstrated these sites are essential to mouse FM activity in mouse embryos. Here we also confirmed by introducing transverse mutations that all these sites are also essential to zfFM activity in zebrafish brain at 24 hpf stage (SI Table 1). In addition, a 29-bp sequence designated as X (Fig. 3A) is conserved in both tetrapods and teleosts (Fig. 3A). A substitution of this X site in the mFM enhancer with BglII linker caused the loss of activity in E8.5 and E9.0 anterior neuroectoderm (Fig. 3E). However, at E9.5 and E10.5, an activity was found in the caudal forebrain and anterior midbrain; it was not in the caudal midbrain (Fig. 3F). The significance of these complicated effects of the X site mutation on the FM activity remains for future studies.

Recently we have found that acetylated Yin Yang 1 (YY1), but not the unmodified one, binds to a sequence in the AN enhancer (underlined in SI Fig. 7A) (N.T. and S.A., unpublished work). Moreover, the AN enhancer is promoter dependent, and YY1 also binds to a sequence in the promoter region (α1 in Fig. 4A). Mutation of either of these YY1 binding sites results in the loss of the AN activity, and the sites are conserved among tetrapods, coelacanth, and skate. However, neither the teleost 366FM regions nor the teleost promoters (α1 in Fig. 4A) possess these YY1-binding sequences. Furthermore, YY1 binding did not occur to the zebrafish 366FM (SI Fig. 8).

To examine the significance of the conversion of one TCF site in tetrapods into the SOX site in teleosts for the AN activity of zfFM region, the zfFM sequence around this site (GTGCATTGTTGGGTG) was converted into the mFM sequence (GGGCTTTGTTCCACT) in zfFM enhancer; however, the conversion did not abolish the early activity in mouse anterior neuroectoderm (data not shown). The X sequence is perfectly conserved among mouse, human, chick, and Xenopus, but a few nucleotides are altered in teleosts (Fig. 3A). The change of these nucleotides into mouse nucleotides in zfFM did not abolish the AN activity either (data not shown). In the 366FM three sequences, FCR1 (CAGGTCGG), FCR2 (GATGTA), and FCR3 (GAAAA), are also uniquely common among teleosts except Fugu Otx2b (Fig. 3A). Transverse mutations in either of these sites also did not affect the zfFM activities in the mouse anterior neuroectoderm at headfold stage (data not shown).

AN and FM Enhancers in Coelacanth and Skate Otx2 Genomes.

The presence of the AN enhancer in tetrapods and its absence in teleosts, together with the acquisition of the AN activity in the teleost FM enhancer, raised a question as to the evolutionary origin of this Otx2 enhancer organization. To address this question, we next examined Otx2 genomes in L. menadoensis (coelacanth) and R. eglanteria (skate); LmOtx2 and ReOtx2 (SI Fig. 9). ReOtx2 was concluded to be Otx2 orthologue not only by its sequence, but also by its expression. In skate embryos, it was expressed in the anterior neural plate before closure at the early somite stage (SI Fig. 9C). At the pharyngeal stage, the expression was found in the forebrain and midbrain with a sharp boundary at the isthmus; the activity was absent in the most rostral part of the brain as seen for mouse Otx2 (9, 12).

Draft sequences were determined on selected BAC clones, and conserved motifs were identified (Fig. 4A). Twenty-four domains are conserved among mouse, human, chick, and Xenopus Otx2 loci. The AN and FM enhancers are encoded in ζ and γ domains, respectively, and both domains are conserved in coelacanth and skate. Among the ten domains 5′ proximal to the coding region, α-κ, at least seven (α, γ-ζ, ι, and κ) are conserved in the skate genome (Fig. 4A). However, there are notable gaps in this region of the skate sequence, and β, η, and θ may be encoded there. The skate situation greatly contrasts with that of teleosts with the conservation of only three domains (α, γ, and θ) in zebrafish Otx2, three domains (γ, η, and ι) in FuguOtx2a, and one domain (γ) in FuguOtx2b.

The 90-bp sequence assigned as the core portion of the AN enhancer (8) is highly conserved in coelacanth and moderately conserved in skate (Fig. 4B and SI Fig. 7A). It is interesting that in the core 100-bp sequence of the FM enhancer conserved in both tetrapods and teleosts, the skate sequence is closer to those of tetrapods and coelacanth than to those of teleosts (Fig. 4C and SI Fig. 7B). In the FM region corresponding to mouse 366 FM, sequences are conserved at 81% between mouse and skate, and at 51% between skate and zebrafish; except for the 100-bp core sequence, zfFM does not align at all to the skate sequences. One OTX and two TCF binding sites are conserved in the skate 100-bp core sequence; one TCF site is not the SOX site, unlike teleosts (SI Fig. 7B). The sequence around the X site is perfectly conserved over 39-bp between skate and tetrapod Otx2 orthologues in contrast to the conservation over a 29-bp domain, with a few nucleotide changes, between teleost and tetrapod orthologues. In the coding 562-bp sequence in the exon 3 that includes a part of the homeodomain, skate Otx2 is most distant, and zebrafish Otx2 is closer to tetrapod Otx2 (SI Fig. 9B).

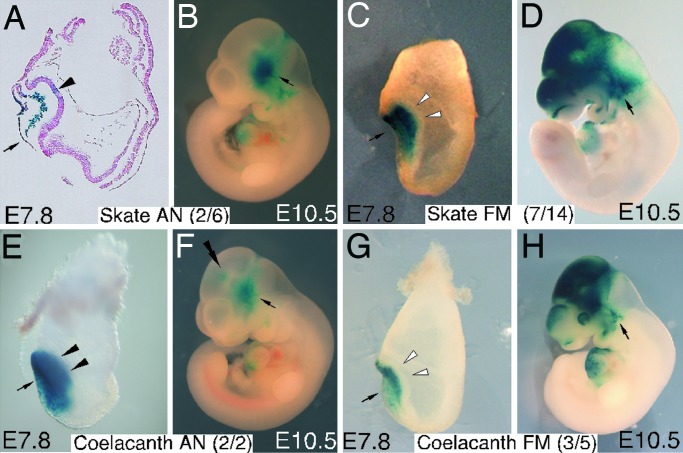

Finally, the enhancer activities of AN (ζ) and FM (γ) regions of skate and coelacanth were determined in mouse embryos. The coelacanth AN region displayed an intense activity in anterior neuroectoderm at E7.8 (Fig. 5E). The activity of the skate AN region was also apparent in the neuroectoderm, although somewhat weak (Fig. 5A). Both coelacanth and skate AN regions were inactive in E10.5 mouse brain (Fig. 5 B and F). On the other hand, neither the skate nor coelacanth FM region exhibited any activity in the anterior neuroectoderm at E7.8 (Fig. 5 C and G), whereas both had activities in forebrain and midbrain at E10.5 (Fig. 5 D and H). There are several activities that appear unique to skate and/or coelacanth FM regions and have not been observed in tetrapod FM regions (cf. Fig. 1 D and H). Nevertheless, the present study indicates that AN and FM enhancers were already established in the common ancestor of extant gnathostomes and that the AN enhancer was lost in the teleost lineage along with the acquisition of the AN activity in the FM enhancer.

Fig. 5.

Activity pattern of skate (A–D) and coelacanth (E–H) AN (A, B, E, and F) and FM (C, D, G, and H) regions during mouse anterior neuroectoderm development. Solid (A and E) and open (C and G) arrowheads indicate the presence or absence, respectively, of the β-gal expression in anterior neuroectoderm. Double arrowheads in F indicate a faint expression in diencephalon, the significance of which remains for future study. Activities were determined by establishing permanent transgenic lines. See Fig. 1 legends for arrows. (A) A sagittal view. (B–H) Lateral views (anterior is toward the left).

Discussion

AN and FM Enhancers Are Phylogenetically Deeply Conserved.

It has been proposed that vertebrate evolution was brought about primarily by changes in networks among existing genes rather than acquisition of new genes (2, 3). Changes in gene networks are changes in upstream and downstream and cooperating factors. The changes would have taken place mostly in transcription-regulatory cis elements or enhancers of relevant genes. Changes in coding regions or protein structures would have made minor contribution. Several studies have strongly suggested that Otx gene products are functionally equivalent throughout gnathostomes (13–15).

Transcription factor-binding motifs are short (in the range of 8–10 bp) and would have been frequently changed throughout evolutionary time. Several studies have demonstrated enhancers that yield the same expression patterns among different species but of which underlying sequences are highly dissimilar (16–19). A survey of cis sequences whose functions are experimentally verified in 51 human genes estimated that 32–40% of these sequences are not functional in rodents (20). In contrast, in vertebrates interspecific sequence comparison of the intergenic region is now a routine method to physically identify putative enhancers (21). Both the AN and FM enhancers are well conserved not only in tetrapods, but also in coelacanth and skate over a >400-million-year period of divergence. Two Tcf binding sites, one Otx binding site, and one X site (>39 bp) are also perfectly conserved, including their number, order, and direction as well as the spacing (22, 23). The Otx2 expression driven by these enhancers is essential for development of the mouse rostral neuroectoderm and midbrain/caudal forebrain, respectively, protecting them against caudalization into Gbx2-positive metencephalon (8, 9). The enhancer architecture composed of the AN and FM enhancers must have been established in the common ancestor of gnathostomes, thus allowing Otx2 expression in anterior neuroectoderm. The Otx2 functions established with these enhancers must have been imperative for brain development in the ancestral gnathostome such that the enhancer architecture remained tightly conserved. It will be intriguing to determine whether the AN and FM enhancers exist in lamprey, a primitive jawless vertebrate. In gnathostomes, Otx genes consist of three paralogous lineages, Otx1, Otx2, and Otx5, whereas lampreys have at least two, if not three, Otx paralogues: OtxA and OtxB in Lethenteron japonicum (24) and PmOtx in Petromyzon marinus, which aligns to neither OtxA nor OtxB (25).

As far as we know, this study represents the first example that has demonstrated the tight sequence and functional conservation of enhancers across a broad spectrum of gnathostomes, including a chondrichthyian and a crossopterygian. Other studies have demonstrated shared conserved sequences across wide phylogenetic distances, however, the actual functional dissection of these conserved elements has been lacking. For example, the HoxA clusters of human and horn shark were shown to share a striking degree of cis-sequence conservation, although it remains to be determined systematically whether the conserved sequences are indeed functional (26, 27). Tight conservation of enhancers from ancestral gnathostomes to mammals may be a general phenomenon for those developmental genes essential to the vertebrate body plan.

AN and FM Enhancers Are Uniquely Diverged in Teleost Lineage.

Contrasting with the strong conservation of the AN and FM enhancers among tetrapods, coelacanth, and skate, the enhancer sequence organization is not conserved in teleosts. In addition, among the ten domains (α-κ) that are conserved among tetrapods at the 5′-proximal to the Otx2 coding region, at least seven (α, γ-ζ, ι, and κ) are conserved in the skate genome. In contrast, in this region only three domains are conserved in zfOtx2, three domains in FuguOtx2a, and one domain in FuguOtx2b. Noncoding sequence motifs are also extensively conserved in HoxA cluster between the human and horn shark, but the majority of the motifs have been lost in zebrafish (27). A recent study reported that only ≈10% of 104 mouse enhancers experimentally validated have homologous sequences in zebrafish (28), and several reports have suggested that the genome has changed rapidly in teleost lineage. There was a whole genome duplication (WGD) very early in the teleost radiation (29, 30). The duplication would have brought about radical remodeling in the teleost genome, being accompanied with gene degeneration and complementation (31, 32). The change in the Otx2 enhancer organization in teleosts might be a direct result of this event. However, against the expectation of the duplication-degeneration-complementation model, all teleost Otx2 orthologues examined lack the AN enhancer. In addition, most of the domains conserved in tetrapod Otx2 loci are not present in either zebrafish Otx2, Fugu Otx2a, or Otx2b. It is conceivable that the loss of the AN enhancer and the acquisition of AN activity in the FM enhancer occurred before the WGD in the bony fishes. Polypterus (bichir) represents a teleost lineage that diverged before the WGD (33) and would be a good target for future study because it would alleviate the difficulties brought to bear by the duplicated genomes (34).

The possibility should be kept in mind that teleosts may have evolved a divergent form of the AN enhancer; the AN activity of the teleost FM region might have a supporting or synergistic activity. In addition, we have not overlooked the possibility that the change in the Otx2 enhancer organization in teleosts might be related to functional divergence among Otx paralogues in these fishes. In tetrapods, Otx2, but not Otx1, is considered to play a major role in each step of head development. However, the expression data suggest that the specialization of Otx2 and Otx1 functions might be diverged in the lineage leading to the extant teleosts, although absence of functional analysis precludes concluding this possibility (35).

Upstream Factors that Regulate Otx2 Expression in Anterior Neuroectoderm.

Our findings raise a major question as to whether the AN activity in the teleost FM enhancers was established by using the same or different upstream factors as used for nonteleost AN enhancers. No sequence exists that is conserved over more than five nucleotides between tetrapod 90AN and teleost 366FM but is not present in tetrapod 366FM. Sequences responsible for the AN activity exist in the 3′ half of the 366FM region (158zfFM). YY1 binding to both the AN enhancer and promoter, which are separated by some 90 kb, is requisite for mouse AN activity (N.T. and S.A., unpublished data); these YY1-binding sites are conserved not only among tetrapods but also in coelacanth and skate (SI Fig. 7A). However, neither the teleost 366FM nor the teleost promoters (α1) possess these YY1-binding sequences. No YY1 binding occurred to the zfFM enhancer. In the 3′ half of the 366FM region, several sequences are uniquely common among teleosts, whereas they are absent in nonteleosts. Neither of these sites, however, had an effect on its AN activity, and the identification of the sequences in the zebrafish 366FM region responsible for its AN activity remains for future studies. However, it is strongly suggested that zebrafish FM enhancer acquired its AN activity by capturing upstream factors different from those that direct the nonteleost AN enhancers. Most intriguing is the fact that nevertheless the zebrafish FM enhancer is active in the mouse anterior neuroectoderm at headfold stage.

Materials and Methods

Production of Transgenic Animals.

mFM and zfFM are the ApaI/HindIII 1.4-kb mouse and corresponding 0.6-kb zebrafish genomic DNAs, respectively, described in ref. 9. Lengths and primers used to isolate genomic sequences containing the mouse 366FM, zebrafish 366FM, Fugu Otx2a FM, and Otx2b FM, skate AN and FM regions, and coelacanth AN and FM regions by PCR are indicated in SI Table 2. For transgenic analysis in mouse, each enhancer region was inserted into the NotI and SacII sites of 1.8-kb LacZ (8); transgenic mice or embryos were generated as described (8). For the assay in zebrafish embryos, a 1.2-kb zebrafish genomic region proximal to the zfOtx2 translation start site served as the promoter; it was inserted in frame into the SgfI site at the translational start site of the EGFP gene in the pEGFP-N1 (Promega). This construct, zfOtx2promoter-EGFP, does not have any activity to drive the EGFP expression during zebrafish embryogenesis until 48 hpf stage (data not shown); zfFM-EGFP and mFM-EGFP were generated by inserting zfFM and mFM in the SmaI site of zfOtx2promoter-EGFP reporter cassette. Transgenic zebrafish were produced by cytoplasm injection of 10 ng/μl closed circular plasmid DNA into the one-cell stage of fertilized zebrafish embryos. Mutations in zfFM and mFM were introduced by the PCR-based method (8).

Cloning of Skate and Coelacanth Otx2 Genes.

To identify Otx2 genes in clear nose skate, R. eglanteria, and Indonesian coelacanth, L. menadoensis, a seminested degenerate PCR was performed for exon 3 as described (36) by using skate and coelacanth genomic DNA. The products thus obtained were verified by sequencing and used to screen BAC libraries of each species (37, 38) to identify the BAC clones containing the Otx2 loci. Draft sequences of BAC clones were determined by shotgun sequence method; conserved motives among animals were determined by using VISTA and BLAST programs (8).

RNA in Situ Hybridization.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization analysis in zebrafish embryos was performed with digoxigenin and/or fluorescein-labeled probes of the zfOtx2 and EGFP as described (35). Whole-mount and serial section in situ hybridization in skate embryos was performed with the DNA fragment for exon 3 as described (11).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mr. Kenichi Inoue, Ms. Tomoe Bunno, and Dr. Kohei Hatta for their help in making transgenic animals; Dr. Hiroshi Sasaki and Dr. Masayoshi Mishina for providing plasmids; and Dr Hiroyuki Takeda for providing genomic information of medaka. We also thank the Laboratory for Animal Resources and Genetic Engneering and the Research Aquarium in RIKEN CDB for housing of animals. This work was supported by a grant-in-aid for Scientific Research on Priority Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. C.T.A. and T.M. were supported, in part, by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation.

Abbreviations

- AN

anterior neuroectoderm enhancer

- En

embryonic day n

- FM

fore- and midbrain

- mFM

mouse FM

- zfFM

zebrafish FM.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0604686103/DC1.

References

- 1.Gans C, Northcutt RG. Science. 1983;220:268–274. doi: 10.1126/science.220.4594.268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carroll SB, Grenier JK, Weatherbee SD. From DNA to Diversity: Molecular Genetics and the Evolution of Animal Design. Oxford: Blackwell; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davidson EH. Genomic Regulatory Systems. San Diego: Academic; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simeone A, Acampora D, Gulisano M, Stornaiuolo A, Boncinelli E. Nature. 1992;358:687–690. doi: 10.1038/358687a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Acampora D, Mazan S, Lallemand Y, Avataggiato V, Maury M, Simeone A, Brulet P. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1995;121:3279–3290. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.10.3279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ang SL, Jin O, Rhinn M, Daigle N, Stevenson L, Rossant JA. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1996;122:243–252. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Matsuo I, Kuratani S, Kimura C, Takeda N, Aizawa S. Genes Dev. 1995;9:2646–2658. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.21.2646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kurokawa D, Takasaki N, Kiyonari H, Nakayama R, Kimura-Yoshida C, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2004;131:3307–3317. doi: 10.1242/dev.01219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurokawa D, Kiyonari H, Nakayama R, Kimura-Yoshida C, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2004;131:3318–3331. doi: 10.1242/dev.01220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Acampora D, Avantaggiato V, Tuorto F, Barone P, Perera M, Choo D, Wu D, Corte G, Simeone A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:1417–1426. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.7.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suda Y, Nakabayashi J, Matsuo I, Aizawa S. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:743–757. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.4.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simeone A, Acampora D, Mallamaci A, Stornaiuolo A, D'Apice MR, Nigro V, Boncinelli E. EMBO J. 1993;12:2735–2747. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05935.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leuzinger S, Hirth F, Gerlich D, Acampora D, Simeone A, Gehring WJ, Finkelstein R, Furukubo-Tokunaga K, Reichert H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1998;125:1703–1710. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.9.1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nagao T, Leuzinger S, Acampora D, Simeone A, Finkelstein R, Reichert H, Furukubo-Tokunaga K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:3737–3742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acampora D, Boyl PP, Signore M, Martinez-Barbera JP, Ilengo C, Puelles E, Annino A, Reicchert H, Corte G, Simeone A. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2001;128:4801–4813. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.23.4801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ludwig MZ, Bergman C, Patel NH, Kreitman M. Nature. 2000;403:564–567. doi: 10.1038/35000615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bertrand V, Hudson C, Caillol D, Popovici C, Lemaire P. Cell. 2003;115:615–627. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00928-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oda-Ishii I, Bertrand V, Matsuo I, Lemaire P, Saiga H. Development (Cambridge, UK) 2005;132:1663–1674. doi: 10.1242/dev.01707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takahashi H, Mitani Y, Satoh G, Satoh N. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1999;126:3725–3734. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dermitzakis ET, Clark AG. Mol Biol Evol. 2002;19:1114–1121. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a004169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sumiyama K, Kim C-B, Ruddle FH. Genomics. 2001;71:260–262. doi: 10.1006/geno.2000.6422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anand S, Wang WCH, Powell DR, Bolanowski SA, Zhang J, Ledje C, Pawashe AB, Amemiya CT, Shashikant CS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:15666–15669. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2535667100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erives A, Levine M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3851–3856. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400611101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ueki T, Kuratani S, Hirano S, Aizawa S. Dev Genes Evol. 1998;208:223–228. doi: 10.1007/s004270050176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomsa JM, Langeland JA. Dev Biol. 1999;207:26–37. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim C-B, Amemiya C, Bailey W, Kawasaki K, Mezey J, Miller W, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Wagner G, Ruddle F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1655–1660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.030539697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiu C, Amemiya C, Dewar K, Kim C-B, Ruddle F, Wagner GP. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5492–5497. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052709899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Plessy C, Dickmeis T, Chalmel F, Strähle U. Trends in Genet. 2005;21:207–210. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Amores A, Force A, Yan YL, Joly L, Amemiya C, Fritz A, Ho RK, Langeland J, Prince V, Wang YL, et al. Science. 1998;282:1711–1714. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Postlethwait JH, Yan YL, Gates MA, Horne S, Amores A, Brownlie A, Donovan A, Egan ES, Force A, Gong Z, et al. Nat Genet. 1998;18:345–349. doi: 10.1038/ng0498-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ohno S. Evolution by Gene Duplication. Heidelberg: Springer; 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Force A, Lynch M, Pickett FB, Amores A, Yan YL, Postlethwait J. Genetics. 1999;151:1531–1545. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoegg S, Brinkmann H, Taylor JS, Mayer A. J Mol Evol. 2004;59:190–203. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2613-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chiu CH, Dewar K, Wagner GP, Takahashi K, Ruddle F, Ledje C, Bartsch P, Scemama JL, Stellwag E, Fried C, et al. Genome Res. 2004;14:11–17. doi: 10.1101/gr.1712904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li Y, Allende ML, Finkelstein R, Weinberg ES. Mech Dev. 1994;48:229–244. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(94)90062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Germot A, Lecointre G, Plouhinec J-L, Le Mentec C, Girardot F, Mazan S. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1668–1678. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Danke J, Miyake T, Powers T, Schein J, Shin H, Bosdet I, Erdmann M, Caldwell R, Amemiya CT. J Exp Zool A Comp Exp Biol. 2004;301:228–234. doi: 10.1002/jez.a.20024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cannon JP, Haire RN, Mueller MG, Litman RT, Eason DD, Tinnemore D, Amemiya CT, Ota T, Litman GW. Immunogenetics. 2006;58:362–373. doi: 10.1007/s00251-006-0112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fossat N, Courtois V, Chatelain G, Brun G, Lamonerie T. Dev Dyn. 2005;233:154–160. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimura C, Takeda N, Suzuki M, Oshimura M, Aizawa S, Matsuo I. Development (Cambridge, UK) 1997;124:3929–3941. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kimura C, Yoshinaga K, Tian E, Suzuki M, Aizawa S, Matsuo I. Dev Biol. 2000;225:304–321. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.