Abstract

Context: Research into the effects of ice on neuromuscular performance is limited, and the results sometimes conflict.

Objective: To examine the effects of ice bag application to the anterior thigh and active warm-up on 3 maximal functional performance tests.

Design: A 2 × 2 repeated-measures design with 4 randomly assigned treatment conditions: (1) no ice/no warm-up, (2) ice/ no warm-up, (3) no ice/warm-up, and (4) ice/warm-up.

Setting: Gymnasium with a wooden floor.

Patients or Other Participants: Twenty-four active, uninjured men, 18 to 24 years of age.

Intervention(s): For the ice application, we applied an ice bag with compression to the anterior thigh for 20 minutes. Warm-up (6.5 minutes) consisted of 3 minutes of jogging, 3 minutes of stretching, and ten 2-legged vertical jumps.

Main Outcome Measure(s): Maximal performance of 3 functional fitness tests: single-leg vertical jump height, shuttle run time, and 40-yd (36.58-m) sprint time.

Results: Significant main effects were noted for both ice and warm-up for all functional tests, with a significant interaction (ice × warm-up) for the 40-yd sprint test. Ice bag application negatively affected performance on all 3 functional tests; warm-up significantly improved posticing performance. High-intensity maximal performance after ice bag application almost returned to the no ice/no warm-up pretreatment levels with the addition of active warm-up and time.

Conclusions: Ice bag application negatively affected performance of maximal high-intensity functional tests. Active warm-up and time for muscle warming after ice bag application decreased the detrimental effects of icing on functional performance.

Keywords: cryotherapy, modalities, agility, sprint, vertical jump

Sports medicine professionals use various forms of cold application on a daily basis to treat both acute and chronic athletic injuries. It is essential that these clinicians know about the physiologic effects of cold in order to provide care and to select the most appropriate cold application protocols for athletes. The physiologic effects of cold application include decreases in metabolism, inflammation, pain, and muscle spasm and increases in tissue stiffness. 1–3 Cold application decreases the responsiveness of the neuromuscular system, including nerve conduction velocity and specific reflex activity. 2, 4 Maximal muscular force development has been shown to decrease, increase, or not change after cold application, depending on the site of ice application. 5–7

Various factors (eg, compression, thickness of adipose tissue, type of cold modality, duration of ice application, prior physical activity) may enhance or diminish the depth of cold penetration and, therefore, the effectiveness of cold application. 2, 3, 8–10 Enwemeka et al 11 reported that when chemical cold packs were applied, the depth of tissue temperature reduction (ie, cooling) extended only 1 cm into the muscle tissue. In 2001, Myrer et al 12 observed that temperature varied at 1-cm (skin) and 3-cm (intramuscular) depths when using an ice bag treatment. These reductions depended on the amount of subcutaneous fat between the ice bag and the muscle. 12

Bags of crushed ice are inexpensive and readily available and can cool more effectively than other cold modalities, such as chemical cold packs. 2, 8 Ice bag application provides longer decreases in muscle temperature than does ice massage. 13 In addition, Myrer et al 14 noted that applying cold via a whirlpool with water at 10°C prolonged muscle temperature decreases (ie, rewarming was slower) when compared with ice pack application. The depth of cold penetration increases when the duration of cold application increases, as well as when compression is applied with the cold modality. 2

In 1996, Cross et al 15 reported that ice immersion of the lower leg up to the fibular head negatively affected functional performances (lower height achieved on single-leg vertical jump, slower time on agility shuttle run). In contrast, Evans et al 16 showed no difference in agility test scores between subjects whose feet and ankles were cooled and those whose feet and ankles were not cooled before functional testing. These studies were similar in that both used functional performance tests; however, the contradictory findings could be due to the differences in the amount of tissue cooled (ie, lower leg versus foot and ankle). Further research is needed to verify these observations. 15, 16 Previous authors have not isolated a large muscle group, such as the quadriceps, for examining functional performance after cold application. 15, 16 Ice bag application to the quadriceps may affect maximal functional performance.

Before participating in exercise or sport performances, most individuals warm up. Warm-up prepares the exerciser both physiologically and psychologically for exercise. Although the effects of cold application on functional performance have been studied, the effects of active physical warm-up after cold application have not been well controlled in previous research. 15, 16 Palmer and Knight 17 measured the rate of tissue rewarming with mild activity (walking with crutches, simulated dressing and showering) after 20, 30, and 40 minutes of ice application. Myrer et al 18 determined that intramuscular temperature returned to precooling temperatures within 10 minutes when exercise (treadmill walking at 5.63 km/h) immediately followed a 20-minute ice bag treatment. Cross et al 15 and Evans et al 16 only included warm-up activities of walking 2 minutes followed by 45 seconds of stretching the treated musculature and 30 seconds of stretching activities of the participant's choice after cooling but before functional performance testing. Neither the duration nor the type of active warm-up was consistent among these studies of cold application and functional performance. Additional information about active warm-up after ice bag application is needed to ensure optimal performance and to prevent injury when athletic trainers and other sports medicine professionals consider the return of an athlete to competition. It would be beneficial to have a protocol for active warm-up that would overcome any negative effects that cold application may have on maximal functional performance. Therefore, our purpose was to examine the effects of ice bag application to the anterior thigh on 3 measures of maximal functional performance. A second purpose was to investigate the effect of active warm-up on functional performance after the application of an ice bag to the anterior thigh.

METHODS

Design

We used a 2 × 2 repeated-measures design for this investigation. The independent variables were ice (ice bag application: ice or no ice) and warm-up (6.5 minutes of active stretching and calisthenics: warm-up plus time or no warm-up). The dependent variables were single-leg vertical jump height, time to complete the agility shuttle run, and time to complete the 40-yd (36.58-m) sprint.

Sample Size Determination

Sample size was determined a priori using G*Power (version 2.1.2; University of Trier, Trier, Germany), 19 with the level of significance set at P = .05 and power (1 − β) = .80 in order to detect a large effect ( f 2 > 0.1). 20 We conducted a pilot study with 6 participants to evaluate the effect size for each independent variable (ie, the magnitude of the difference between means of the dependent variables). Based on these a priori calculations and the pilot study, we set the final sample size at n = 24.

Subjects

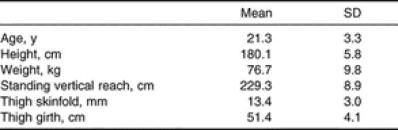

Twenty-four physically active men (18 to 24 years of age) from northwest Ohio volunteered for the study. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. To be eligible for the study, subjects either had to be a member of an intramural or varsity athletic team or had to participate in physical activity (cardiovascular and/or weight training) at least 3 times per week. All subjects included in the study were free from injury of the lower extremities, cardiac conditions (eg, hypertension, coronary artery disease), and hypersensitivity to cold. Participants provided informed consent and completed a medical history questionnaire before data collection. Approval from the Human Subjects Review Board of the institution was received before subject recruitment and data collection.

Table 1. Subjects' Demographic Data (n = 24).

Instrumentation

We used 3 measures of maximal functional performance: single-leg vertical jump, agility shuttle run, and 40-yd sprint. Single-leg vertical jump height was measured in centimeters using a tape measure on the wall. An electronic stopwatch was employed to time the 40-yd sprint and agility shuttle run. All maximal functional performance tests were completed on a wooden gymnasium floor. A Lange skinfold caliper was used to measure the skin and subcutaneous fat skinfold thickness at an anterior midpoint on the thigh midway between the top of the patella and the flexion point for hip flexion.

Procedures

Each participant attended an orientation session to become familiar with the testing procedures. Measurements of height, weight, standing vertical reach, thigh skinfold, and thigh girth were taken during the orientation session. The subjects performed 3 practice trials of each of the 3 functional tests to ensure proper technique. Each individual self-selected his preferred leg, and this extremity was cooled and tested in the single-leg vertical jump. All measurements were taken while the participants were wearing athletic shoes and athletic apparel; the same shoes and clothing were worn for each testing session.

Conditions

Participants were randomly assigned to a control group and 3 experimental groups using a Williams square design as follows:

Control condition (no ice/no warm-up): 20 minutes of rest, followed by the 3 functional performance tests.

Experimental condition (no ice/warm-up): 20 minutes of rest, followed by 6.5 minutes of active warm-up and completion of the 3 functional performance tests.

Experimental condition (ice/no warm-up): 20 minutes of ice application to the anterior thigh, followed by functional performance testing.

Experimental condition (ice/warm-up): 20 minutes of ice application to the anterior thigh and 6.5 minutes of active warm-up, followed by functional performance testing.

Ice and Active Warm-Up Routine

Each ice bag comprised 3 lb (1.36 kg) of crushed ice in a 1-gal (3.79-L) plastic bag, and the ice bag was applied with a compression wrap. The active warm-up routine included both direct and indirect warm-up. It consisted of 3 minutes of light jogging followed by 3 minutes of stretching. Two minutes were allowed for general stretching, which consisted of the butterfly stretch for the inner thigh and groin, seated hamstring stretch, seated spinal twist for lower back and gluteal muscles, and standing calf stretch for gastrocnemius and soleus muscle groups. One minute was given for quadriceps stretching, which consisted of both side-lying and standing quadriceps stretches lasting 30 seconds each. All other stretches were performed bilaterally, with 15 seconds allotted for each side. Stretching was followed by ten 2-legged vertical jumps. The 2-legged jumps were performed with a counterforce movement using both arms, and participants were instructed to jump as high as possible. The total time for the entire warm-up routine was approximately 6.5 minutes.

Test and Condition Order

The order of the 3 maximal functional tests was balanced by a Williams square design to control for order and carryover effects. The Williams square included all possible combinations of functional testing orders, and an equal number of participants was randomly assigned to each order of testing. Each subject also received a different order for each condition before functional testing by random reassignment of the Williams square.

Functional Tests

Three tests of functional performance, single-leg vertical jump, agility shuttle run, and 40-yd sprint, were performed within each testing condition. We required a period of at least 4 hours between the no-ice conditions and a period of 24 hours between ice application sessions. A 1-minute rest period was allowed between maximal functional tests. Three trials of each test were performed, with a 30-second rest period between trials. The best score from the 3 trials for each test was used for data analysis. The reliability of each test was also assessed after data collection.

Single-leg vertical jump. The single-leg vertical jump was performed by the treated extremity. Each participant, with chalk dust on his fingers, stood with the treated-extremity side of his body next to the wall marked in increments by centimeters. Each subject was instructed to place the opposite arm behind his back while raising the arm nearest to the wall vertically over his head and to stand only on the leg closest to the wall. Using a countermovement, the participant jumped vertically as high as possible and touched the wall with his fingertips at the apex of his jump. Eliminating the learned arm movement helped to ensure that only leg power was assessed. 21 It has been reported 22 that a single-leg vertical jump closely simulates the functional stability encountered during sport activities. Johnson and Nelson 21 reported the reliability of this test as r = .98 and the validity as r = .99 for college men.

Agility shuttle run. The participants were instructed to begin at the starting line and sprint to touch a line 30 ft (9.14 m) from the starting line, then sprint back to the starting line, and repeat. The test began when the tester shouted a “go” command. The tester started the stopwatch once the first movement was detected, and time was recorded to the nearest 0.01 second. Fleishman 23 reported the reliability of this test as r = .85.

40-yard sprint. The 40-yd sprint began with the subjects in a forward lunge position with the treated leg forward. Again, the test began when the tester shouted a “go” command, and timing began when the first movement was detected. Time was recorded to the nearest 0.01 second. Adams 24 reported the reliability of this test as r = .90.

Statistical Analyses

We calculated statistical analyses for the 3 functional tests using the statistical software Super ANOVA (version 1.11; Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA). 25 Intratest reliability was assessed for each of the 3 functional performance tests using an intraclass correlation coefficient ( R) with data from the control condition (no ice/no warm-up). 26 The formula R = MS S − MS E/MS S, where MS S = mean squares of the subjects and MS E = mean squares of the treatment plus error, was used. 26

A 2 × 2 (ice × warm-up), 2-way repeated-measures analysis of variance was calculated for each dependent variable. Retrospective statistical power (1 − ß) and an effect size index ( f 2) were calculated a posteriori using G*Power. 19 The f 2 was selected for the power analysis because of the 2-way repeated-measures design. 19, 27 The effect size for each independent variable is defined as the magnitude of the difference between the means expressed in SD units. 19, 20, 27 The f 2 is typically interpreted as follows: f 2 = .02, small effect; f 2 = .15, medium effect; and f 2 = .35, large effect. 19 Typically, α is set at .05 and β at .20 to reduce the probability of type I and type II errors, respectively. 27 Percentage differences were calculated using the formula ([pretreatment − posttreatment]/pretreatment) × 100. Means, SDs, and SEMs (SEM = SD/[n 1/2]) were calculated for the dependent variables.

RESULTS

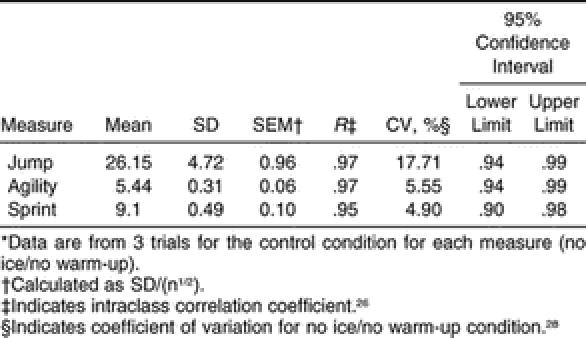

Reliability of Functional Performance Tests

Intraclass reliability was assessed for each of the 3 functional performance tests from results for the no ice/no warm-up condition. The 3 trials of each test were highly correlated: vertical jump, R = .97, coefficient of variation = 17.71%; agility, R = .97, coefficient of variation = 5.55%; and sprint, R = .95, coefficient of variation = 4.9% ( Table 2).

Table 2. Intraclass Reliability Coefficients for Functional Performance Tests (n = 24)*.

Single-Leg Vertical Jump

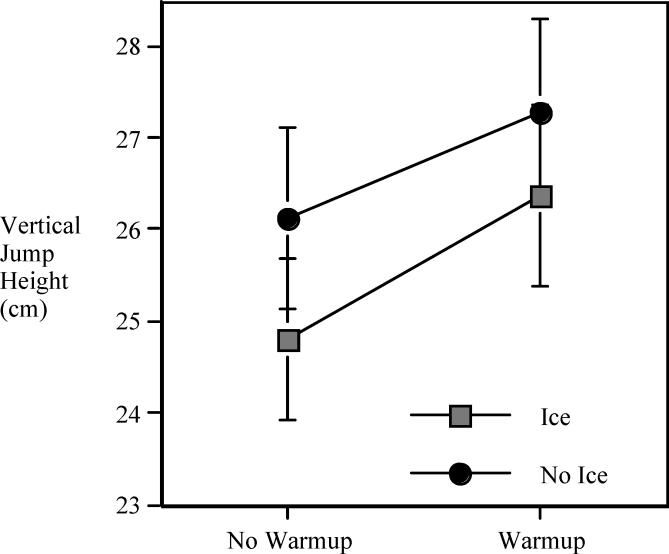

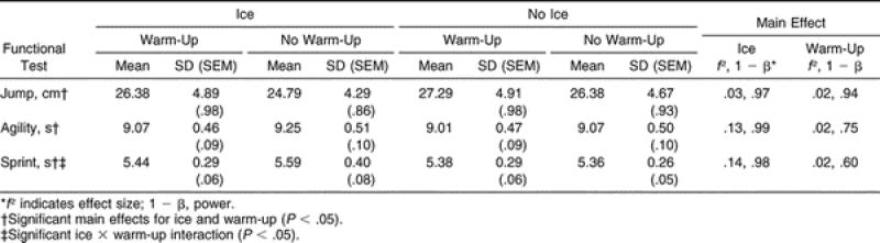

The mean for vertical jump was 1.25 cm lower (−4.7%) when the participants had an ice bag application (F 1,23 = 16.91, P = .0004, f 2 = .03 [main effect for ice]). The means for vertical jump without separation by warm-up condition were 26.83 ± 4.76 cm for no ice and 25.58 ± 4.62 cm for ice (n = 48). The mean for vertical jump was 1.25 cm greater (+4.9%) when the subjects were instructed to warm up, regardless of ice application (F 1,23 = 13.91, P = .0011, f 2 = .02 [main effect for warm-up]). The means for vertical jump without separation by ice condition were 26.83 ± 4.87 cm for warm-up and 25.58 ± 4.51 cm for no warm-up (n = 48). When the warm-up followed the ice bag application (ice/ warm-up), performance improved over the ice/no warm-up condition ( Table 3). No significant interaction was noted between the ice and warm-up conditions for the single-leg vertical jump ( Figure 1).

Table 3. Scores on 3 Functional Measures by Ice and Warm-Up Conditions (n = 24).

Figure 1. Vertical jump height performance for the 2 treatment conditions: ice/no ice and warm-up/no warm-up. Ice bag application reduced performance, and active warm-up after icing improved performance.

Agility Shuttle Run

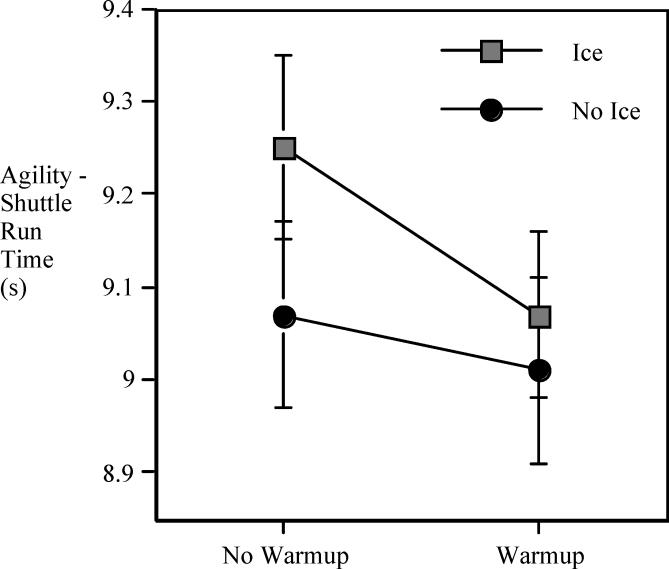

Participants completed this test 0.12 seconds (−13.8%) more slowly when they had an ice bag application (F 1,23 = 26.92, P = .0001, f 2 = .13 [main effect for ice]). The means for agility shuttle run without separation by warm-up condition were 9.04 ± 0.48 seconds for no ice and 9.16 ± 0.49 seconds for ice (n = 48). When the subjects actively warmed up before the agility shuttle run, they finished 0.12 seconds (+1.3%) faster than when they did not warm up (F 1,23 = 7.55, P = .0114, f 2 = .02 [main effect for warm-up]). The means for agility shuttle run without separation by ice condition were 9.04 ± 0.46 seconds for warm-up and 9.16 ± 0.51 seconds for no warm-up (n = 48). The ice condition (ice/no warm-up) caused the subjects to perform more poorly on the agility shuttle run, but when combined with a warm-up (ice/warm-up), these times improved ( Table 3). No interaction was noted between the ice and warm-up conditions for the agility shuttle run ( Figure 2).

Figure 2. Agility shuttle run time performance for the 2 treatment conditions: ice/no ice and warm-up/no warm-up. Ice bag application reduced performance, and active warm-up after icing improved performance.

40-Yard Sprint

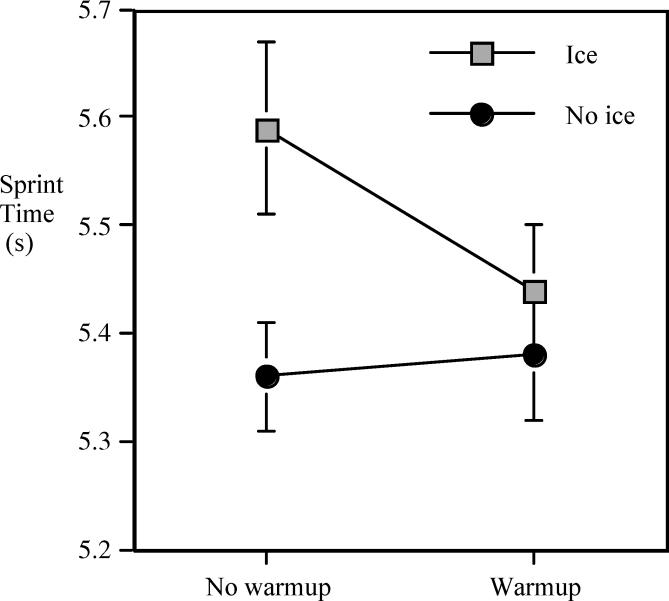

A significant ice × warm-up interaction was recorded for the 40-yd sprint (F 1,23 = 5.26, P = .03) ( Figure 3). The combined effects of ice bag application and warm-up significantly changed sprint times. Sprint times improved significantly (0.15 seconds, 2.7%) when an active warm-up followed the ice bag application (ice/warm-up; Table 3). However, warm-up did not improve sprint time (no ice/warm-up). Subjects in the no ice/ no warm-up condition had the fastest mean 40-yd sprint times. As was the case with the other 2 functional performance tests, we also noted main effects for ice and warm-up. Participants were 0.15 seconds slower (−2.7%) when they had an ice bag application (main effect of ice) (F 1,23 = 19.50, P = .0002, f 2 = .14). The means for sprint without separation by warm-up were 5.37 ± 0.28 seconds for no ice and 5.52 ± 0.35 seconds for ice (n = 48).

Figure 3. Sprint time performance for the 2 treatment conditions: ice/no ice and warm-up/no warm-up. Ice bag application reduced performance, and active warm-up after icing improved performance. The interaction was significant for sprint time.

DISCUSSION

The effects of ice bag application to the anterior thigh on 3 measures of maximal functional performance were investigated. Ice bag application for 20 minutes was detrimental to maximal performance on the 3 functional tests: single-leg vertical jump (−4.7%), agility shuttle run (−13.8%), and 40-yd sprint (−2.7%). A 6.5-minute active warm-up and time after the ice bag application offset the effects of ice bag application but did not allow for performances to return to the level of performances after no ice/warm-up.

Cross et al 15 reported similar decreases in functional performance for the single-leg vertical jump and the agility shuttle run after ice immersion of the lower leg in a cold whirlpool at 13°C for 20 minutes. Interestingly, Cross et al 15 tested university athletes who had better overall functional performance scores than the participants in the present study, but the performance decrements were relatively similar between the two studies when comparing the no ice/no warm-up and ice/no warm-up conditions. Vertical jump height decreased more than 1 cm, and agility shuttle run times increased more than 0.1 second after ice application in both studies ( Table 3). It should be noted that these decrements occurred even though different muscles were cooled (gastrocnemius versus quadriceps).

Each functional performance test measures a different aspect of explosive power. The vertical jump test measures the immediate generation of anaerobic power. 29 The 40-yd sprint test (an “all-out” test completed in 6 to 8 seconds) represents an individual's capacity for adenosine triphosphate-phosphocreatine in the activated muscle. 29 The time in the agility shuttle run is not only highly dependent on power output but also on the individual's ability to change body position. The decrements in all of these maximal functional performance tests may be explained by the effects of cold application on the quadriceps. Cold application to the muscle has been shown to decrease motor nerve conduction velocity, decrease maximal strength, and increase tissue stiffness. 2, 4, 5, 30 Ruiz et al 30 reported that after 25 minutes of ice application to the quadriceps, concentric and eccentric isokinetic force production decreased significantly. Kinzey et al 31 reported a decline in vertical impulse after a 20-minute ice bath immersion to the lower leg. 31 Vertical impulse represents force applied over time and indicates the accelerating force during a jump. 31 When ice was applied to the lower extremity, vertical impulse for the 1-legged vertical jump was decreased for approximately 10 minutes. The decrease in vertical impulse has been previously attributed to the depressive effects of cooling on motor nerve conduction velocity. 31 Further details concerning the mechanisms of cold application on muscle and nerve function have been summarized by Kowal 32 and Swenson et al. 33

In contrast to our results and the findings by Cross et al 15, Evans et al 16 reported no effect for immersion of the foot and ankle to 8 cm above the lateral malleolus in cold water (1°C) for 20 minutes on 3 tests of agility. Maximal performances in the functional tests in our study decreased with the quadriceps (anterior thigh) iced. From these findings, it appears that cold application to muscular areas such as the lower leg and thigh produces greater decreases in agility test performances than does application to a joint such as the ankle. 15, 16 The type of muscle treated, the type of functional test, and the site of ice application should be controlled in future studies.

Some authors have recorded skin and intramuscular temperature changes in the quadriceps after icing 17 as well as the time course for rewarming of various muscles. 18 Although we did not measure skin and intramuscular temperatures, it seems plausible that performance increases after icing with warm-up were due to muscle warming. Long et al 34 reported that when no activity was performed after 20 minutes of ice bag application to the quadriceps, the subcutaneous temperature was approximately 6°C lower (1-cm depth) and intramuscular temperature was 5°C lower (2-cm depth). Myrer et al 14 reported that after ice bag application of 20 minutes to the left calf, the gastrocnemius intramuscular temperature cooled by −7.1°C and warmed only 0.3°C ± 0.9°C after 5 minutes and 0.5°C ± 0.6°C after 10 minutes of rest.

Our second purpose was to examine the effects of active warm-up after cold application. Active warm-up (ie, involving exercise) improves short-term performance (by less than 10 seconds) more than passive heating alone. 35 We found that active warm-up for 6.5 minutes after ice bag application significantly improved performance on the single-leg vertical jump and the agility shuttle run. The significant ice × warm-up interaction for the 40-yd sprint indicated that warm-up did not improve performance on the sprint in the no-ice condition but did have a positive effect after ice application. The specificity of the warm-up may be one reason for the unexpected interaction with the 40-yd sprint. The active warm-up in most athletic settings is specific to the skills to be performed and helps to prepare the body for the type of activity and energy systems to be used. The 3-minute jog as part of the warm-up for this study was intended to be an indirect warm-up used to increase core temperature and was not intended to be specific to the 40-yd sprint or the agility shuttle run. Different energy systems and muscle fiber types are used for jogging and sprinting. Bottinelli et al 36 suggested that different muscle fiber types (fast twitch and slow twitch) respond differently to changes in temperature. This concept is corroborated by Ruiz et al, 30 who iced subjects' quadriceps for 25 minutes and then had them exercise (15 minutes of bicycle ergometry at 60% of V̇ o 2max). A significant increase was noted in concentric but not eccentric force production of the quadriceps 20 minutes after ice application.

When exercise is added to the posticing time period, muscle temperature increases rapidly. In 2000, Myrer et al 18 applied ice bags for 20 minutes to subjects' left calves. After 5 minutes of walking at 5.63 km/h (3.5 mi/h) on the treadmill, intramuscular temperature warmed approximately 2°C, and by 10 minutes posticing, temperature was within −0.61°C ± 1.46°C of the pretreatment temperature. In addition, Ruiz et al 30 reported that 25 minutes of ice bag application decreased concentric and eccentric muscle torque production. If subjects cycled at a moderate intensity after ice application, then concentric muscle force production recovered, but eccentric muscle force production did not. In another combination of ice bag application and exercise, Bender et al 37 noted that walking during the actual application of ice resulted in decreases in subcutaneous temperature but not deep tissue cooling. Based on the results of the present study and muscle temperature data from other studies, we believe that 6.5 minutes of warm-up and time allowed the performance of the muscle to return to levels that were almost comparable with those associated with the no-ice condition performance. In the future, evaluating the tissue temperature throughout icing and warm-up procedures would be helpful in determining possible time courses and mechanisms for performance changes.

It should be noted that for the ice/no warm-up condition, the participants immediately began their testing condition after completing the ice bag treatment. Completion of the warm-up allowed 6.5 minutes of time to elapse before the beginning of the testing procedure. Therefore, the warm-up condition is not only the warm-up treatment but also the amount of time that elapsed while the warm-up was completed. No condition was completed without warm-up. Thus, the confounding effects of ice and injury cannot be addressed by our investigation. Although the muscle probably did not significantly rewarm in 6.5 minutes with rest, based on findings from previous authors, future researchers may allow the subjects in the ice/no warm-up condition to rest and rewarm the muscle for the same amount of time that is allotted for a warm-up routine in order to specifically identify the effects due solely to the active warm-up, as opposed to the effects due to the warm-up combined with time. Whether this effect for ice/warm-up was due to the time lapse between the ice bag application and functional test, to the actual warm-up procedure we implemented in our study, or to a combination of both is uncertain.

Although it is unlikely that a healthy athlete or performer would have ice applied to muscle before a maximal performance, our results indicate that active warm-up and time before situations in which maximal performances are required reduce the effects of ice bag application on functional performance. In the excitement of team competition, athletes may be anxious to return to participation. The time course for rewarming the muscle and reaching readiness for activity lies in the judgment of the certified athletic trainer. Based on our findings, exercisers may be ready for maximal performance in approximately 6.5 minutes with active warm-up. Certainly, future authors should directly measure skin and intramuscular temperature to specifically delineate the time course for rewarming various muscles. However, as Cross et al 15 indicated, functional performance tests allow for immediate feedback to the athletic trainer concerning the quantitative status of the athlete. These tests could be performed on the sidelines before the athlete returns to activity.

Well-designed studies are constructed so that statistical as well as practical significance can be detected, if present. 27 By changing α, sample size, size of the population SD, or the magnitude of the difference that is determined to be considered worth detecting among the means, the power of a test can be changed. 27 Our study was designed with sufficient power to detect differences due to icing and warm-up based on a priori power calculations. Power is defined as the probability of concluding that there is a difference among the means when in actuality a true difference exists (ie, correct rejection of the null hypothesis). 27 Typically power is set at .8 or 80%, thereby setting the chance of a type II error at .2 or 20%. Type II error means that the researchers concluded incorrectly that there was no difference among the means when in actuality a difference exists. The magnitude of the differences among the means in our study (ie, effect sizes; Table 3) may be considered small. The sample size, power, and α were sufficient to detect these small differences among the means. For icing, the effect size for the single-leg vertical jump test was small ( f 2 = .03), with medium effect sizes for the agility shuttle run ( f 2 = .13) and the 40-yd sprint ( f 2 = .14). Applying an ice bag resulted in small and medium decreases in maximal functional performances. To some athletes, this difference may not be practically significant for performing their event if they are unable to warm up posticing, which is not recommended (eg, football lineman returning to blocking). However, for others who desire maximal performance, knowledge of icing and the time course for muscle warming may be of importance (eg, basketball forward jumping and competing for a rebound). Athletes and exercisers are advised not to perform activity without warm-up because of the increased chance of injury. However, this condition was used in the present study to determine the effects of ice and warm-up on these functional performance tests.

More research is needed in the area of the active warm-up (ie, exercise) after ice bag application. Although a longer duration of warm-up time may improve performance test scores, a 10-minute warm-up after a 20-minute icing session may not be practical or feasible in athletic situations. Therefore, future investigators may study the effects of an “activity-specific” warm-up after ice application. The warm-up we used incorporated a 3-minute jog, stretching, and 10 double-legged vertical jumps. The functional tests performed in the study were the single-leg vertical jump, agility shuttle run, and 40-yd sprint. Using a warm-up with movements more similar to the activities to be performed may speed rewarming and be beneficial to performance after icing.

It is common for athletes with minor injuries to apply ice to a body part and then return to competition. Certainly we did not measure the combined effects of icing and injury, and whether the results from our study can be generalized to an injured population after icing is unknown. However, our findings do add to the knowledge base of athletic trainers and other sports medicine professionals, who should be aware of the extent of physiologic responses to cold application as well as the potentially detrimental effects on maximal physical performance. Because active warm-up has been shown to potentially counteract the negative effects of ice application on performance, we recommend that if ice is applied to a large muscle group, active warm-up should follow ice application before return to activity. Future authors may further examine the duration and type of warm-up activities (eg, stretching versus dynamic exercise). In our study, ice bag application to the anterior thigh significantly decreased performance in the single-leg vertical jump, agility shuttle run, and 40-yd sprint. Also, active warm-up and time after ice application significantly improved performance in all of these functional tests.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Patricia Shewokis and Dr Michael Liang for their initial input into the study.

REFERENCES

- Halvorson GA. Therapeutic heat and cold for athletic injuries. Physician Sportsmed. 1990;18(5):87–92, 94. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1990.11710045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight KL. Cryotherapy in Sport Injury Management. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1995: 9,65–67,68,130–132.

- McMaster WC. Cryotherapy. Physician Sportsmed. 1982;10(11):112–119. doi: 10.1080/00913847.1982.11947373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mecomber SA, Herman RM. Effects of local hypothermia on reflex and voluntary activity. Phys Ther. 1971;51:271–281. doi: 10.1093/ptj/51.3.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall MW. Effect of temperature on muscle force and rate of muscle force production in men and women. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20:74–80. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CTM, Young K. Effect of temperature on the contractile properties and muscle power of triceps surae in humans. J Appl Physiol. 1983;55:191–195. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.1.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang MTC, Hsieh HS, Che JJ. Effect of intramuscular temperature on muscle strength and fatigue index in elite sprinters. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1992;24:S92. (suppl 5) [Google Scholar]

- McMaster WC, Liddle S, Waugh TR. Laboratory evaluation of various cold therapy modalities. Am J Sports Med. 1978;6:291–294. doi: 10.1177/036354657800600513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick MA, Knight KL, Ingersoll CD, Potteiger JA. The effects of ice and compression wraps on intramuscular temperatures at various depths. J Athl Train. 1993;28:236–245. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrofsky JS, Lind AR. Insulative power of body fat on deep muscle temperatures and isometric endurance. J Appl Physiol. l975;39:639–642. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1975.39.4.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enwemeka CS, Allen C, Avila P, Bina J, Konrade J, Munns S. Soft tissue thermodynamics before, during, and after cold pack therapy. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:45–50. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200201000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrer JW, Myrer KA, Measom GJ, Fellingham GW, Evers SL. Muscle temperature is affected by overlying adipose when cryotherapy is administered. J Athl Train. 2001;36:32–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemke JE, Andersen JC, Guion WK, McMillan J, Joyner AB. Intramuscular temperature responses in the human leg to two forms of cryotherapy: ice massage and ice bag. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1998;27:301–307. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1998.27.4.301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrer JW, Measom G, Fellingham GW. Temperature changes in the human leg during and after two methods of cryotherapy. J Athl Train. 1998;33:25–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross KM, Wilson RW, Perrin DH. Functional performance following an ice immersion to the lower extremity. J Athl Train. 1996;31:113–116. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans TA, Ingersoll C, Knight KL, Worrell T. Agility following the application of cold therapy. J Athl Train. 1995;30:231–234. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmer JE, Knight KL. Ankle and thigh skin surface temperature changes with repeated ice pack application. J Athl Train. 1996;31:319–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myrer JW, Measom GJ, Fellingham GW. Exercise after cryotherapy greatly enhances intramuscular rewarming. J Athl Train. 2000;35:412–416. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner A, Faul F, Erdfelder E. G*Power: A Priori, Post-Hoc, and Compromise Power Analyses for the Macintosh. Version 2.1.2. Trier, Germany: University of Trier; 1997.

- Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum and Assoc; 1998.

- Johnson BL, Nelson JK. Practical Measurements for Evaluation in Physical Education. 3rd ed. Minneapolis, MN: Burgess Publishing; 1979.

- Risberg MA, Ekeland A. Assessment of functional tests after anterior cruciate ligament surgery. J Orthop Sport Phys Ther. 1994;19:212–217. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.19.4.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleishman EA. The Structure and Measurement of Physical Fitness. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1964.

- Adams GM. Exercise Physiology Laboratory Manual. 3rd ed. Boston, MA: WCB/McGraw-Hill; 1998.

- Abacus Concepts. Super ANOVA. Berkeley, CA: Abacus Concepts; 1989.

- Vincent WJ. Statistics in Kinesiology. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 1995.

- Kirk RE. Experimental Design: Procedures for the Behavioral Sciences. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole Publishing; 1995.

- Hopkins WG. A new view of statistics. Available at: http://sportsci.org/ stats/. Accessed August 3, 2006 .

- McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition and Human Performance. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2001:224–228.

- Ruiz DH, Myrer JW, Durrant E, Fellingham GW. Cryotherapy and sequential exercise bouts following cryotherapy on concentric and eccentric strength in the quadriceps. J Athl Train. 1993;28:320–323. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzey SJ, Cordova ML, Gallen KJ, Smith JC, Moore JB. The effects of cryotherapy on ground reaction forces produced during a functional task. J Sport Rehabil. 2000;9:3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal MA. Review of the physiological effects of cryotherapy. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1983;5:66–73. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1983.5.2.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson C, Sward L, Karlsson J. Cryotherapy in sports medicine. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.1996.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long BC, Cordova ML, Brucker JB, Demchak TJ, Stone MB. Exercise and quadriceps muscle cooling time. J Athl Train. 2005;40:260–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop D. Warm up II: performance changes following active warm up and how to structure the warm up. Sports Med. 2004;33:483–498. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200333070-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottinelli R, Canepari M, Pellegrino MA, Reggiani C. Force-velocity properties of human skeletal muscle fibres: myosin heavy chain isoform and temperature dependence. J Physiol. 1996;495:573–586. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender AL, Kramer EE, Brucker JB, Demchak TJ, Cordova ML, Stone MB. Local ice-bag application and triceps surae muscle temperature during treadmill walking. J Athl Train. 2005;40:271–275. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]