Abstract

Context: Increased contracture of the dominant posterior shoulder in throwing athletes has been associated with the development of altered shoulder rotational motion as well as several shoulder conditions. Clinicians must be able to accurately and reliably measure posterior shoulder contractures during the evaluation of such athletes in order to provide appropriate treatment.

Objective: To evaluate the reliability and validity of assessing posterior shoulder contracture by measuring supine glenohumeral (GH) horizontal adduction.

Design: Descriptive with repeated measures.

Setting: The biomechanics laboratory at Illinois State University (Normal, IL) and the athletic training room in Surprise, AZ.

Patients or Other Participants: Twenty-four shoulders were tested in 12 subjects (age = 21.9 ± 4.3 years, height = 175.0 ± 10.0 cm, mass = 82.4 ± 19.1 kg) for determination of reliability, and 46 shoulders were tested in 23 professional baseball pitchers (age = 21.25 ± 1.66 years, height = 190.0 ± 5.0 cm, mass = 88.45 ± 6.99 kg) for determination of validity.

Main Outcome Measure(s): We examined intratester and intertester reliability over 3 testing sessions by having 2 examiners measure GH horizontal adduction with the subject in a supine position with the scapula stabilized. To determine the validity and clinical usefulness of this measurement, we examined the relationship between GH horizontal adduction motion and internal shoulder rotational motion among a group of baseball pitchers.

Results: Intraclass correlation coefficients were high for intratester (0.93, SEM = 1.64°) and intertester (0.91, SEM = 1.71°) measurements. This measurement was also shown to have a moderate to good relationship with lost internal shoulder rotational motion ( r = .72, P = .001) of the dominant arm among the baseball pitchers.

Conclusions: Based on the results of this study, we found that measuring GH horizontal adduction with the subject supine and the scapula stabilized is a reliable and valid technique for assessing posterior shoulder contracture.

Keywords: range of motion, throwing athletes

The deceleration phase of the throwing motion (−500 000°·s −2) creates large compressive forces (1090 ± 110 N) on the shoulder. 1, 2 These repetitive forces have been speculated to result in secondary changes, such as contracture of the posterior shoulder capsule. 3, 4 This contracture may contribute to alterations in shoulder rotation, such as decreased internal and increased external motion rotational. 3, 5–9 Furthermore, increases in posterior shoulder tightness and decreases in shoulder internal rotation have been clinically and empirically linked to several conditions, including subacromial impingement, 5, 10 superior labrum anterior-posterior (SLAP) lesions, 3 and internal impingement. 11 However, recent investigators have reported no side-to-side differences in anterior or posterior glenohumeral (GH) translation in professional baseball pitchers, indicating that contracture of posterior soft tissue structures other than the capsule may be causing these rotational differences and pathologic characteristics. 12 Regardless of which soft tissue structures are contracted, this loss of motion is strongly associated with the development of shoulder injury. Therefore, accurate assessment of posterior shoulder motion is a necessary measurement in the recognition of pathologic shoulder characteristics.

Several measurement techniques to assess posterior shoulder contracture have been reported in the literature 4, 8, 13; however, debate still exists as to which is the best technique. Most techniques attempt to produce an accurate measurement of true GH horizontal adduction. Although these measurements ultimately assess the same motion, several discrepancies among techniques have led to confusion regarding the best method. One of the earliest measurements 13 was performed by measuring horizontal adduction with a goniometer while the subject lay in a supine position. Unfortunately, proper scapular stabilization may not have been maintained, leading to accessory scapulothoracic movement and inaccurate findings. A second technique 4 required the examiner to stabilize the scapula while the subject was supine, yet no reliability or validity data have been reported. For a third technique, 8 the subject lies on his or her side, so that an imaginary line connecting the acromions is perpendicular to the examination table, while the examiner manually stabilizes the scapula in a retracted position. A second examiner then measures the distance from the patient's medial epicondyle to the examination table surface, thereby eliminating the need for potentially inaccurate goniometer readings. However, if the upper torso and acromions are even slightly rotated in an anterior-posterior direction, this measurement will produce inaccurate results. Also, maintaining this alignment may prove difficult during passive horizontal adduction. Furthermore, a subject with a longer humerus will naturally have a shorter distance to the examination table than a patient with a shorter humerus, thus making comparison among patients difficult.

Clinicians may be inclined to simply measure shoulder internal rotation motion as the best indicator of posterior shoulder contracture. 9, 14 However, because of the effects of increased humeral retroversion on decreasing internal rotational motion, 15–19 this bony adaptation may be misinterpreted as posterior shoulder contracture. Despite the debate, humeral adduction motion appears to be a consistent indicator of true posterior shoulder motion, even though sufficient data with regard to reliability and validity have yet to be documented.

Despite the need for an accurate method of assessing posterior shoulder motion, complicated techniques and/or lack of reliability and validity among the several techniques currently available have added to the confusion surrounding this topic. Therefore, the purpose of this study is to report on the reliability, concurrent validity, and clinical usefulness of assessing posterior shoulder contractures by assessing GH horizontal adduction with the subject in the supine position.

METHODS

Subjects

To determine the reliability of this GH horizontal adduction measurement technique, we tested 12 physically active subjects (age = 21.9 ± 4.3 years, height = 175.0 ± 10.0 cm, mass = 82.4 ± 19.1 kg). To test concurrent validity, 23 professional baseball pitchers (age = 21.25 ± 1.66 years, height = 190.0 ± 5.0 cm, mass = 88.45 ± 6.99 kg) completed bilateral GH horizontal adduction and internal and external rotation range-of-motion testing. No participants reported a recent history (within 2 years) of shoulder injury or any previous shoulder surgeries. Each subject provided informed consent before the study, as mandated by the university institutional review board, which also approved the study.

Instrumentation

We used the Pro 3600 Digital Inclinometer (SPI-Tronic, Garden Grove, CA) to measure GH horizontal adduction motion and internal and external shoulder rotation motion. This device provides a real-time digital reading of all angles in a 360° circle with respect to either a horizontal or vertical reference and is accurate up to 0.1°, as reported by the manufacturer. The digital inclinometer was modified with a reference line positioned along the midline of the device, which was used for proper alignment of anatomical landmarks.

Intratester Reliability Analysis

Subjects in the reliability study attended 3 testing sessions, with 48 hours between sessions. One of 2 randomly selected examiners was used for intratester reliability, with the examiner blinded to all 3 measurements recorded for each subject. Each examiner completed the intratester measurements on 12 separate shoulders (examiner 1 measured 12 shoulders on 3 different occasions, examiner 2 measured the other 12 shoulders on 3 different occasions). These examiners were both certified athletic trainers and had performed more than 300 assessments using this technique.

Intertester Reliability Analysis

Intertester reliability testing occurred during one of the intratester sessions. For intertester reliability, the second examiner assessed GH horizontal adduction motion approximately 5 minutes after the first examiner's measurement. The order in which the examiners completed their measurements was randomized.

Concurrent Validity Analysis

To test the concurrent validity of the measurement, one examiner assessed GH horizontal adduction, while a second examiner, who was blind to the previous GH horizontal adduction measurement, assessed internal and external rotation motion. Total arcs of motion were calculated and compared to determine if there was a statistically significant difference bilaterally. Total arc of motion was determined based on the sum of total internal and external rotational motion.

Glenohumeral Horizontal Adduction Measurement

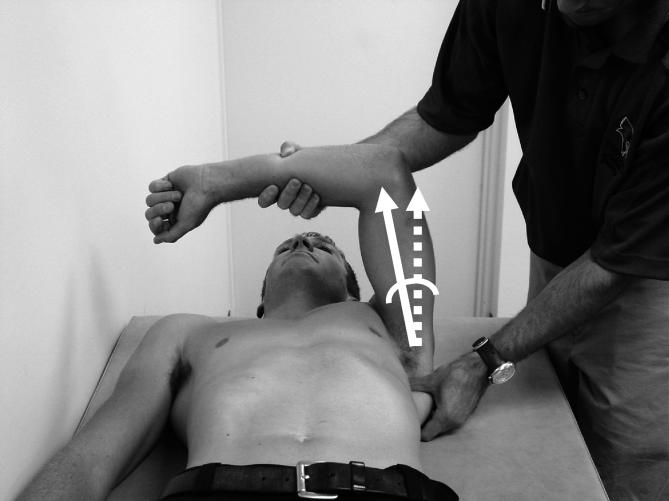

To assess GH horizontal adduction, subjects were positioned supine with both shoulders flush against a standard examination table. The tester stood at the head of the examination table toward the head of the subject and positioned the test shoulder and elbow in 90° of both abduction and flexion. The tester stabilized the lateral border of the scapula by providing a posteriorly directed force (toward the examination table) ( Figure 1) to limit scapular protraction, rotation, and abduction motions. The tester's opposite hand then held the proximal portion of the subject's forearm, slightly distal to the elbow, and passively moved the humerus into horizontal adduction. At the end range of horizontal adduction, a second tester recorded the amount of motion present. To measure GH horizontal adduction, the digital inclinometer was aligned with the ventral midline of the humerus. The angle created by the end position of the humerus with respect to 0° of horizontal adduction (perpendicular plane to the examination table, as determined by the digital inclinometer) ( Figure 2) was then recorded as the total amount of GH horizontal adduction motion.

Figure 1. Stabilization of the scapula during posterior shoulder measurement.

Figure 2. Angle created by the end position of the humerus with respect to the starting position (perpendicular plane to the examination table).

Shoulder Internal-External Rotation Measurement

One measurement of internal shoulder rotation was conducted with the subject in the supine position, with the shoulder and elbow in 90° of abduction and flexion and the humerus supported to ensure a neutral horizontal position (humerus level with acromion process). The humerus was passively internally rotated while the examiner's other hand stabilized the scapula until termination of humeral rotation. At this position, the digital inclinometer was aligned with the ulna (using the olecranon process and the ulnar styloid for reference), 20 thereby providing an angle between the forearm and a perpendicular plane to the examination table. This process was then repeated for external rotation measurements. We assessed a priori intratester reliability of the rotation measurements. Twenty shoulders without any previous injury or surgery were measured using an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) (2,k) formula. Each subject's rotation motion was measured and then reassessed approximately 24 hours later. The ICC and standard error of measurement (SEM) values for external and internal rotational motion were 0.95 and 3° and 0.98 and 2°, respectively.

Reliability Data Analysis

We used an ICC (2,k) formula

21 and calculation of the SEM (SPSS version 11.5; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) to determine the reliability and precision of repeated measures within testers and between the 2 testers. The SEM was calculated

22 as SD ×

.

.

Validity Data Analysis

To assess the validity of the measurement, we used dependent t tests to determine if the baseball pitchers had significant differences in the total arc of motion, GH horizontal adduction, and internal rotation motion of their dominant shoulders compared with the nondominant shoulders. These findings were considered significant at an alpha level of P < .05. The Pearson product moment coefficient of correlation ( r) was calculated to determine if a relationship existed between the total arc of motion and internal rotation and GH horizontal adduction and internal shoulder rotation motion in the dominant arm of the baseball pitchers. A general classification system was used, with correlation coefficient values of .75 or higher considered good, values of .75 to .50 considered moderately reliable, and values below .50 considered poor. 23

RESULTS

Intratester and Intertester Reliability

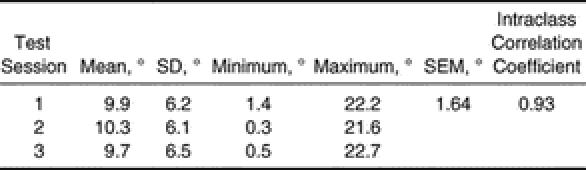

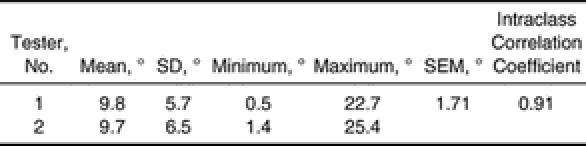

The intratester and intertester reliability of this method for measuring posterior shoulder contracture resulted in ICC and SEM values of 0.93 and 1.64° and 0.91 and 1.71°, respectively ( Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1. Intratester Reliability Analysis of Glenohumeral Joint Horizontal Adduction Measurement (1 of 2 Testers Measuring 24 Shoulders).

Table 2. Intratester Reliability Analysis of Glenohumeral Joint Horizontal Adduction Measurement.

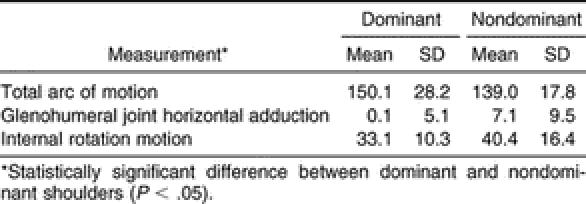

Concurrent Validity

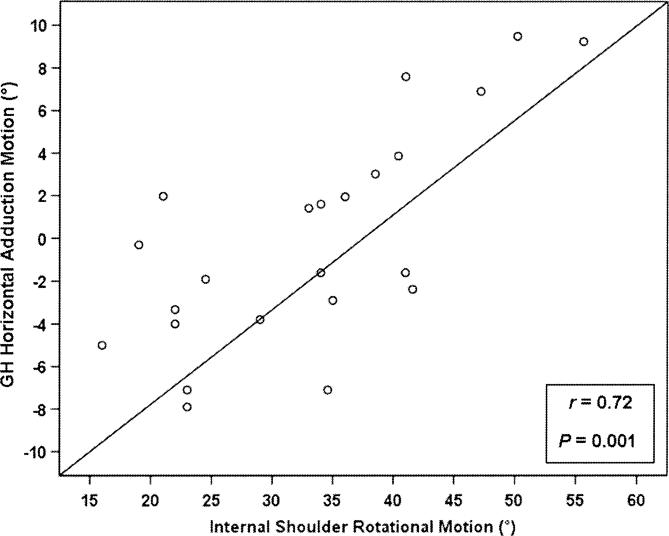

The mean and SD values for total arc of motion, GH horizontal adduction, and internal rotation motion of the dominant and nondominant shoulders of the baseball players are shown in Table 3. The dominant shoulders of the baseball pitchers demonstrated a statistically significant decrease in total arc of motion ( P = .03). Statistically significant differences were also noted in GH horizontal adduction motion ( P = .001) and internal shoulder rotation motion ( P = .001) of the dominant arm compared with the nondominant arm. A moderate to good linear relationship existed between GH horizontal adduction motion and internal shoulder rotation motion ( r = .72, P = .001) of the dominant shoulder of the baseball pitchers ( Figure 3). The coefficient of determination ( r 2 = .52) demonstrated that 52% of the error variance could be explained by common variables of the 2 measurements. A similar relationship between GH horizontal adduction motion and internal shoulder rotational motion was seen in the nondominant shoulders ( r = .68, P = .001). A moderate to good linear relationship also existed between total arc of motion and internal rotation motion ( r = .67, P = .001) of the dominant shoulders.

Table 3. Shoulder Range of Motion° of Baseball Pitchers (n = 23).

Figure 3. Linear relationship between glenohumeral (GH) joint horizontal adduction motion and internal shoulder rotation motion in the dominant arms of baseball pitchers.

DISCUSSION

Athletes involved in throwing and other sports requiring ballistic shoulder rotation commonly display the posterior shoulder contractures that have been implicated in several shoulder conditions. 3, 5, 10 Therefore, an accurate and reproducible clinical technique for measuring contracture is essential for the proper evaluation, prevention, and treatment of these athletes and their respective injuries.

Although previous investigators 3, 5, 10 have reported that the specific contributor to the development of different shoulder conditions is a tight posterior shoulder capsule, we realize the difficulty in assuming that the posterior capsule can be isolated during any measurement. Therefore, we propose that the measurement used in this study evaluates the motion of the structures in the posterior shoulder region, such as the posterior deltoid, infraspinatus, teres minor, and latissimus dorsi muscles, as well as the posterior capsule.

Intratester and Intertester Reliability

Poor reliability and high amounts of measurement error reduce the usefulness of a clinical measurement. Our results show high reliability (intratester ICC = 0.93 and intertester ICC = 0.91) when assessing posterior shoulder contracture by measuring GH horizontal adduction with the scapula stabilized and the subject supine. Furthermore, intratester and intertester SEM values were 1.64° and 1.71°, respectively. These SEM values refer to the hypothetical difference between the actual score of an examiner's assessment and the examiner's observed score during a specific measurement. 22 These reliability and measurement error values demonstrate that this measurement allows the tester an accurate and easily reproducible assessment of motion. The starting position of the measurement is easily determined by the contact of the scapula with the examination table. In this position, the lateral border of the scapula is readily palpable and, therefore, may be stabilized, not only from protraction but also from tilting, rotation, and abduction. Goniometric measurement of GH horizontal adduction may prove difficult and subjective when attempting to align the axis with the GH center and the stationary and moveable arms with bony landmarks. The use of a relatively inexpensive digital inclinometer eliminates these difficulties; the digital inclinometer need only be aligned with the axis of the humerus. The GH joint center does not need to be estimated, and a precise plane perpendicular to the examination table is automatically determined by the inclinometer. The digital inclinometer significantly reduces the number of subjective estimations needed by the examiner and allows for easy, reproducible, and accurate measurements for determining GH horizontal adduction. One disadvantage of this measurement is that it requires 2 examiners to accurately complete the assessment.

Concurrent Validity

Concurrent validity was chosen for this study because the measurement to be validated (assessment of posterior shoulder motion) and the criterion measure (internal rotation motion) were taken at the same time (concurrently), so that both reflected the same behavior. 23 Although we cannot undeniably conclude that comparing internal rotational motion with GH horizontal adduction is the “gold standard” for assessment of posterior shoulder motion, several investigators 3, 5, 7–9, 14 have noted the association between these characteristics, which are currently the best sources for comparison.

Past authors 3, 5, 7–9 have described the association between posterior shoulder contracture and loss of internal rotation motion, especially among throwing athletes. Therefore, to test the validity of the measurement used in this study, we determined if a relationship existed between measuring supine GH horizontal adduction and internal rotation among a group of baseball pitchers. However, first we needed to determine that the loss of internal rotation among the baseball group was, in fact, caused mostly by soft tissue contracture and not by bony adaptations.

Loss of internal rotation motion often equals the gain in external rotation motion, resulting in a total arc of motion (total external rotation + total internal rotation) equal to that of the nondominant shoulder in throwing athletes. 15, 19, 24, 25 Past researchers 15–19 have found that increased humeral retroversion of the throwing shoulder is the cause of these equal total arcs of motion bilaterally. Therefore, to determine the cause of the statistically different arcs of motion among the baseball players in this study, we compared the internal rotation motion values with the statistically different total arcs of motion among the baseball group and found a moderate to good relationship. This relationship illustrates that the loss of internal rotation motion was not entirely a result of increased humeral retroversion. Rather, this difference was most likely due to soft tissue restraints of the posterior shoulder. Thus, to prove the concurrent validity of assessing posterior shoulder motion by measuring supine GH horizontal adduction, a positive relationship should be present between the posterior shoulder motion and internal rotation motion found among the subjects. Our findings supported this concept, resulting in a moderate to good relationship between lost internal shoulder rotation motion and decreased posterior shoulder motion of the dominant arm, thereby verifying the validity of the measurement. Although the Pearson correlation showed a moderate to good association, a large percentage of the error variance could not be explained by common factors. 21 One potential cause of this variance may be the 2 motions occurring in different planes of motion and therefore targeting different areas and soft tissue structures of the posterior shoulder.

The development of posterior shoulder contracture and subsequent loss of internal rotation motion have been associated with several shoulder conditions. 3, 5, 10, 11 Burkhart et al 3 clinically observed the shoulders of 124 baseball pitchers with arthroscopically diagnosed type 2 SLAP lesions. All patients had more than 25° loss of internal rotation and a concomitant posterior shoulder contracture in the involved shoulder compared with the uninvolved shoulder. Harryman et al 10 reported that a tightening of the posterior shoulder capsule resulted in superior translation of the humeral head during flexion, internal rotation motion, and horizontal adduction movements. This superior translation of the humeral head may decrease the subacromial space and result in an increased risk of subacromial impingement. In support of this theory, Tyler et al 5 noted that 31 patients with subacromial impingement had significantly more posterior capsular shortening and lost internal shoulder rotation motion than did subjects in a control group. Myers et al 11 investigated pathologic internal impingement among a population of baseball players. The baseball players diagnosed with internal impingement in their dominant arms had significantly less posterior shoulder motion and lost internal shoulder rotation motion than did a matched group of uninjured baseball players.

Although it is difficult to determine whether the lost posterior shoulder motion and internal rotation were the cause of these various shoulder conditions or whether these conditions caused the lost range of motion, it is clear that a relationship existed between these alterations and injury. Our results are supported by those of previous investigators regarding the accompanying loss of internal rotation motion with increased posterior shoulder contracture ( Figure 3) and emphasize that proper assessment of posterior shoulder motion may be critical in the early detection and treatment of various shoulder conditions.

Early detection and subsequent treatment of posterior shoulder tightness before irreversible shoulder damage occurs may significantly decrease time loss from competition and, ultimately, the need for surgical intervention. 3, 9, 26, 27 Furthermore, this technique may be used to document the progression of contractures in patients during the rehabilitation of various shoulder injuries. Supine GH horizontal adduction has even been described as an effective stretching technique for the soft tissue structures of the posterior shoulder. 24

We acknowledge a few limitations in our study design. The validity portion of the current study was conducted on a highly athletic, healthy population. Other athletes whose sports require different biomechanics and forces on the shoulder or who present with pathologic symptoms may have a different relationship between posterior shoulder contracture and internal rotational motion. However, when this relationship was examined in the nonthrowing shoulder of the baseball pitchers, a moderate to good relationship ( r = .68) was noted, emphasizing that this method of assessment may be suitable for both athletic and nonathletic populations.

Future investigators should focus on measuring posterior shoulder motion in a variety of populations, including baseball players of various performance levels and ages, other overhead athletes, and nonathletic populations, as well as in individuals with various shoulder injuries.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provides data for the measurement of GH horizontal adduction with the subject in the supine position as a reliable and valid method of assessing soft tissue contracture of the posterior shoulder. Given the susceptibility of various overhead athletes to this loss of motion and the potential for injury secondary to such tissue contracture, this technique may prove essential in the proper evaluation, as well as in the development of proper preventive and treatment protocols, of these athletes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Kyle Turner, ATC; Kevin Harmon, ATC; and Jamie Reed, ATC, for their assistance.

REFERENCES

- Pappas AM, Zawacki RM, Sullivan TJ. Biomechanics of baseball pitching: a preliminary report. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:216–222. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Dillman CJ, Escamilla RF. Kinetics of baseball pitching with implications about injury mechanisms. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:233–239. doi: 10.1177/036354659502300218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology, part I: pathoanatomy and biomechanics. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:404–420. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas AM, Zawacki RM, McCarthy CF. Rehabilitation of the pitching shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 1985;13:223–235. doi: 10.1177/036354658501300403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TF, Nicholas SJ, Roy T, Gleim GW. Quantification of posterior capsule tightness and motion loss in patients with shoulder impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2000;28:668–673. doi: 10.1177/03635465000280050801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman MG, Tibone JE, McGarry MH, Veneziani S, Schneider DJ, Lee TQ. A cadaveric model of the throwing shoulder: a possible etiology of SLAP lesions. Paper presented at: 49th Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society; February 2–5, 2003; New Orleans, LA.

- Warner JJ, Allen AA, Marks PH, Wong P. Arthroscopic release of postoperative capsular contracture of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1151–1158. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199708000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler TF, Roy T, Nicholas SJ, Gleim GW. Reliability and validity of a new method of measuring posterior shoulder tightness. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29:262–274. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1999.29.5.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry GC, Hammon D, France P, Norwood LA. The stabilizing function of passive shoulder restraints. Am J Sports Med. 1991;191:26–34. doi: 10.1177/036354659101900105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harryman DT, II, Sidles JA, Clark JM, McQuade KJ, Gibb TD, Matsen FA., III. Translation of the humeral head on the glenoid with passive glenohumeral motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1334–1343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers JB, Laudner KG, Pasquale MR, Bradley JP, Lephart SM. Glenohumeral range of motion deficits and posterior shoulder tightness in throwers with pathologic internal impingement. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:385–391. doi: 10.1177/0363546505281804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsa PA, Wilk KE, Jacobson JA. Correlation of range of motion and glenohumeral translation in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1392–1399. doi: 10.1177/0363546504273490. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warner JJ, Micheli LJ, Arslanian LE, Kennedy J, Kennedy R. Patterns of flexibility, laxity, and strength in normal shoulders and shoulders with instability and impingement. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:366–375. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bey MJ, Kolambkar Y, Herfat M, Hasan SS, Butler DL, Lindenfeld TN. The effects of internal rotation and glenohumeral abduction on posterior capsule strains: a stereophotogrammetric study. Paper presented at: 50th Annual Meeting of the Orthopaedic Research Society; March 7–10, 2004; San Francisco, CA.

- Crockett HC, Gross LB, Wilk KE. Osseous adaptation and range of motion at the glenohumeral joint in professional baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:20–26. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300011701. et al. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osbahr DC, Cannon DL, Speer KP. Retroversion of the humerus in the throwing shoulder of college baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:347–353. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300030801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kronberg M, Brostrom LA. Humeral head retroversion in patients with unstable humeroscapular joints. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1990;260:207–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieper HG. Humeral torsion in the throwing arm of handball players. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:247–253. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260021501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reagan KM, Meister K, Horodyski MB, Werner DW, Carruthers C, Wilk K. Humeral retroversion and its relationship to glenohumeral rotation in the shoulder of college baseball players. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:354–360. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300030901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norkin CC, White DJ. Measurement of Joint Motion: A Guide to Goniometry. Philadelphia, PA: FA Davis; 1995.

- Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. J Strength Cond Res. 2005;19:231–240. doi: 10.1519/15184.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denegar CR, Ball DW. Assessing reliability and precision of measurement: an introduction to intraclass correlation and standard error of measurement. J Sport Rehabil. 1993;2:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of Clinical Research: Applications to Practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall Health; 2000.

- Wilk KE, Meister K, Andrews JR. Current concepts in the rehabilitation of the overhead throwing athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:136–151. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300011201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellenbecker TS, Roetert EP, Bailie DS, Davies GJ, Brown SW. Glenohumeral joint total rotation range of motion in elite tennis players and baseball pitchers. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002;34:2052–2056. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhart SS, Morgan CD, Kibler WB. The disabled throwing shoulder: spectrum of pathology, part III: the SICK scapula, scapular dyskinesis, the kinetic chain, and rehabilitation. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:641–661. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00389-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kibler WB. The role of the scapula in athletic shoulder function. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:325–337. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260022801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]