Abstract

The fate of phage-infected bacteria is determined by the holin, a small membrane protein that triggers to disrupt the membrane at a programmed time, allowing a lysozyme to attack the cell wall. S2168, the holin of phage 21, has two transmembrane domains (TMDs) with a predicted N-in, C-in topology. Surprisingly, TMD1 of S2168 was found to be dispensable for function, to behave as a SAR (“signal-anchor-release”) domain in exiting the membrane to the periplasm, and to engage in homotypic interactions in the soluble phase. The departure of TMD1 from the bilayer coincides with the lethal triggering of the holin and is accelerated by membrane depolarization. Basic residues added at the N terminus of S2168 prevent the escape of TMD1 to the periplasm and block hole formation by TMD2. Lysis thus depends on dynamic topology, in that removal of the inhibitory TMD1 from the bilayer frees TMD2 for programmed formation of lethal membrane lesions.

Keywords: bacteriophage, GxxxG motif, SAR domain, transmembrane domain

Much of the world's biomass is turned over daily in ≈1028 phage infections of bacterial cells (1, 2). For most phages, each infection cycle terminates with the strictly programmed and regulated lysis of the host brought about by two phage-encoded proteins, the endolysin, or lysozyme, and the holin, a small membrane protein that controls lysozyme function (3, 4). During phage assembly, holin molecules accumulate in the cytoplasmic membrane without detectable effect on the host (5, 6). Then, at a time programmed into their primary structure, holins trigger to disrupt the cytoplasmic membrane. For phages like λ and T4, this allows release of an active lysozyme that has accumulated in the cytosol, and holin function is absolutely required for lysis. For others, like P1 and the lambdoid phage 21, the lysozyme is exported by the host sec system and accumulates in the periplasm as an enzymatically inactive form tethered to the membrane by an N-terminal SAR (“signal anchor-release”) sequence (7, 8). Unlike canonical transmembrane domains (TMDs), SAR domains have the unique property of escaping from the bilayer, in part because of an elevated content of relatively nonhydrophobic residues like Gly, Ala, Ser, and Thr (Fig. 1A). Activation of SAR lysozymes requires their release from the bilayer (8). In these cases, holins are not essential for lysis but are thought to impose timing on the lytic event, because holin triggering depolarizes the membrane, and depolarization accelerates the release of the SAR lysozyme from the bilayer (7).

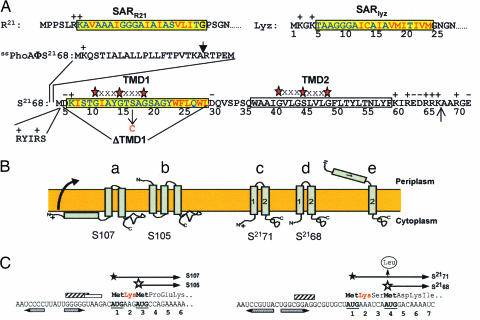

Fig. 1.

Properties of holins and holin genes. (A) Primary structure of S2168 and the N-terminal domains of Lyz, R21, and PhoA. The codon numbering for S2168 follows that of the full-length gene product, S2171 (see C for the dual-start structure at the beginning of S21). The SAR sequences of Lyz and R21 (7, 8) and TMD1 of S2168 (16) are shown in the yellow boxes, with the residues that are polar or neutral in terms of hydrophobicity in blue and the hydrophobic residues in red. TMD2 of S2168 is shown in an uncolored box. The red stars separated by three Xs above the TMDs of S21 indicate GxxxG-like motifs that may mediate interhelical interactions (19). The vertical arrow above the PhoA sequence indicates the normal signal sequence cleavage site (27). In ssPhoAΦS2168, the indicated sequence from PhoA is fused to the Met4 codon of S21. The position of the S16C missense change is indicated by a vertical arrow below the TMD1 sequence. The N terminus of S2168 was given two additional positive charges by inserting the sequence RYIRS between positions 4 and 5. To generate S2168ΔTMD1, the indicated sequence was deleted from S2168. The vertical arrow between residues 66 and 67 indicates the position where the sequence G2H6G2 was inserted in the allele used for purification. (B) Holin topologies. The topologies of the λ antiholin, S107 (a), and holin, S105 (b), are shown (6, 13, 23, 28). (c) and (d) show S2171 and S2168 with two TMDs, respectively. In (e), the lethal form of S21 is shown with its TMD1 in the periplasm. (C) Translational control region of the λ and 21 holin genes (11, 15, 16). Filled and empty stars show starts of the long (antiholin) and short (holin) gene products. Shine-Dalgarno sequences for the first and second translational starts of Sλ are indicated by striped and empty boxes, respectively. The single Shine–Dalgarno sequence of S21 is indicated by a striped box. The horizontal inverted pairs of arrows show the RNA stem loops controlling the dual starts. For S21, the vertical arrow shows the Met-4 → Leu mutation, which eliminates the production of the holin from the allele referred to as S2171. The Lys residues conferring antiholin character to the longer translational product in both the S and S21 genes are shown in red.

Holins are extremely diverse but can be grouped into three classes based on their known or predicted membrane topology (6, 9). The two major classes are class I, with three TMDs, and class II, with two TMDs (Fig. 1B). Many of the genes for class I and class II holins encode two proteins. For example, the coding sequence of the λ S gene begins with codons specifying Met-Lys-Met- (Fig. 1C). Both Met codons are used for translational initiation, giving rise to two proteins, S107 and S105, named for their length in amino acid residues (6, 10–12). These two proteins differ only at their N termini, where S107 has a Met-Lys extension with respect to S105. This small difference has a profound effect on the function of the two proteins; S105 is the holin for phage λ, whereas S107 inhibits membrane disruption by S105 and was the first protein to be designated as an “antiholin” (3, 6). Based on genetic evidence, it was proposed that the antiholin function of S107 derives from the Lys2 residue that, when compared with S105, contributes an extra positive charge to the N terminus. Physiological and biochemical studies indicated that this charge prevents movement of the N terminus, including TMD1, of nascent S107 through the membrane, so that the antiholin has only two TMDs (Fig. 1B) (13). This form of S107 dimerizes with and inhibits S105 (14). Normal or artificial triggering is believed to result in the movement of the N terminus of the S107 protein across the cytoplasmic membrane forming the equivalent of the S105 TMD1 (Fig. 1B). Not only does this new topological isomer of S107 no longer act as an antiholin, it actually contributes to the mass of functional holin in the cytoplasmic membrane of the infected cell (12), presumably making lysis more rapid and efficient (9).

Like λ S, the holin gene of phage 21 also has a dual start and encodes two proteins, a holin, S2168, and an antiholin, S2171 (Fig. 1C) (15, 16). Here, we report unexpected and unprecedented topological changes integral to the function and regulation of this class II holin.

Results

Topology of Nascent S21.

Because of the distribution of positively charged residues along the S2168/S2171 polypeptide chains, the N and C termini are both expected to reside in the cytoplasm of the cell (17). Support for this model was obtained by analyzing the N terminus of purified S2168. S2168, an allele of S21 modified to produce only the S2168 protein (Fig. 1C), was further altered by inserting a DNA sequence encoding an oligohistidine tag between codons 66 and 67 (Fig. 1A). When the resultant allele, S2168his, was expressed and the protein product purified by immobilized-metal ion chromatography, N-terminal sequencing gave the sequence MDKIS with a 94% yield at the first cycle, indicating that the N terminus of S2168 resides initially in the cytoplasm, where it serves as a substrate for the cytoplasmic deformylase. In contrast, the N terminus of TMDs that rapidly exit the cytoplasm and transit the bilayer, like TMD1 of Lep (18) or S105 (R. White, J.F.D., A. Gründling, T. A. T. Tran, and R.Y., unpublished work) retain their fMet residues.

TMD1 Has the Properties of a SAR Domain.

Because TMD1 of nascent S21 is initially membrane-embedded, the topological relationship that exists between the λ holin and antiholin is not possible for their phage 21 analogs. This fact, however, does not preclude the possibility that the primary distinction between S2168 and S2171 is topological. TMD1 of the S2168/S2171 proteins has a composition rich in Gly, Ala, Ser, and Thr, similar to the SAR domains of the P1 and 21 endolysins (Fig. 1A), raising the possibility that TMD1 behaves as a SAR domain and leaves the bilayer as part of its function (Fig. 1B). To determine whether the TMD1 of S21 could function as a SAR domain outside of the holin context, we substituted it for the SAR domain of Lyz, the endolysin of bacteriophage P1 (Fig. 1A). Subcellular fractionation of cells expressing this construct, designated S2168TMD1ΦlyzΔSAR, demonstrated that, like the wild-type Lyz protein, the chimeric protein existed as both membrane-bound and soluble forms with similar masses (Fig. 2A). Moreover, some of the soluble form was periplasmic [see supporting information (SI) Fig. 5], consistent with the initial integration of the chimera with an N-in, C-out topology followed by its subsequent release from the membrane into the periplasm.

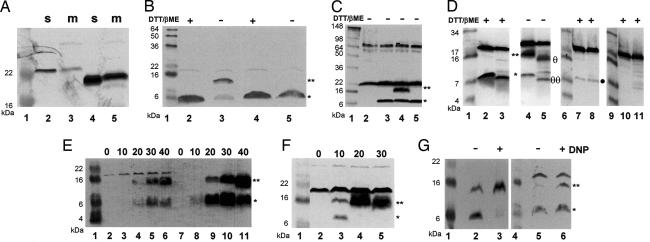

Fig. 2.

TMD1 exits the membrane. Aliquots from cultures expressing the indicated genes were collected by TCA precipitation and analyzed by SDS/PAGE under reducing or nonreducing conditions, as indicated. Except for A, where anti-Lyz antisera were used, separated proteins were detected by Western blotting using antisera raised against the C-terminal peptide of S21. Lane 1 in all panels, lanes 6 and 9 in D and lane 4 in G contain molecular mass standards. In B–G, a star and a double star indicate the positions of the monomer and dimer forms of S2168S16C, respectively. (A) TMD1 of S2168 can substitute for the SAR domain of P1 Lyz. Lanes 2 and 3, S2168TMD1ΦLyzΔSAR; lanes 4 and 5, lyz; m, membrane fraction; s, soluble fraction. FtsI and Rλ were used as controls for the membrane and soluble fractions, respectively (see SI Fig. 6). (B) Dimerization of S2168S16C via its TMD1. Lanes 2 and 3, S2168S16C; lanes 4 and 5, RYIRSΦS2168S16C. Samples taken at 40 min after induction were prepared with or without the reducing agents DTT and β-mercaptoethanol, as indicated. (C) Disulfide formation reflects specific TMD1–TMD1 interactions. Lane 2, vector control; lane 3, S2168; lane 4, S2168S16C; lane 5, S2168G14C. (D) Protease sensitivity of S2168S16C dimers. In this panel, a large format Tris–Tricine gel system was used to allow resolution of the dimer- and monomer-related degradation products. Spheroplasts were prepared, induced for the expression of the indicated S2168 allele, and subsequently digested with proteinase K as described in Materials and Methods. Lanes 2–5, spheroplasts expressing S2168S16C and treated with protease for 0 (lanes 2 and 4) or 5 min (lanes 3 and 5); in lanes 2 and 3, the sample loading buffer contained reducing agents. Lanes 7–8, spheroplasts expressing RYIRSΦS2168S16C and treated with protease for 0 (lane 7) or 5 min (lane 8). Lanes 10–11, induced spheroplasts carrying the plasmid vector treated with protease for 0 (lane 10) or 5 min (lane 11). Symbols θθ and θ to the right of lane 5 indicate the position of the major degradation product of the dimer and monomer forms, respectively. A filled circle to the right of lane 8 indicates the position of the RYIRSΦS2168S16C monomer form. (E) Dimerization of S21 proteins increases as a function of time after induction. Lanes 2–6, S2168S16C; lanes 7–11, S2171S16C. Samples were taken at the times (minutes) indicated above the lanes and subjected to SDS/PAGE without reduction. (F) Direct export of TMD1 accelerates dimerization of the S21 holin. Lanes 2–5, ssphoAΦS2168S16C. Samples were taken at indicated times (minutes) and subjected to SDS/PAGE without reduction. (G) Collapse of the membrane potential accelerates dimerization of S21 proteins. Twenty minutes after induction, DNP was added to one of duplicate cultures expressing either S2168S16C or S2171S16C. Five minutes later, samples were taken from all four cultures and subjected to SDS/PAGE without reduction. Lanes 2 and 3, S2168S16C; lanes 5 and 6, S2171S16C.

TMD1 Is Not Required for S21 Holin Function.

Because TMD1 is capable of exiting the bilayer, it seemed possible that the hole-forming activity of S21 might reside exclusively in TMD2. To test this possibility, we deleted all of the codons for TMD1 from S2168. The resulting construct, S2168ΔTMD1 (Fig. 1A), encodes a bitopic membrane protein of only 44 residues. S2168ΔTMD1 accumulates exclusively in the membrane (SI Fig. 6) and was similar to S2168 in inducible lethality, triggering at a defined time and causing activation of R21, the phage 21 endolysin (Fig. 3A and B). Moreover, as is characteristic of all holins, both S2168 and S2168ΔTMD1 could be triggered prematurely by the addition of the energy poison, dinitrophenol (DNP) (Fig. 3 A and B). Because the expression of the SAR endolysin gene, R21, even in the absence of holin function can result in cell lysis (Fig. 3A; S2168 amR21), the lethality of the S2168ΔTMD1 protein was also determined by using a plasmid encoding the inactive E35Q allele of R21. In this experiment, the triggering of the holin to form a lethal membrane lesion is indicated by the cessation of culture growth. As can be seen in Fig. 3C, S2168ΔTMD1 retains the inducible lethality of the full-length holin, although the time of triggering is delayed compared with the wild type.

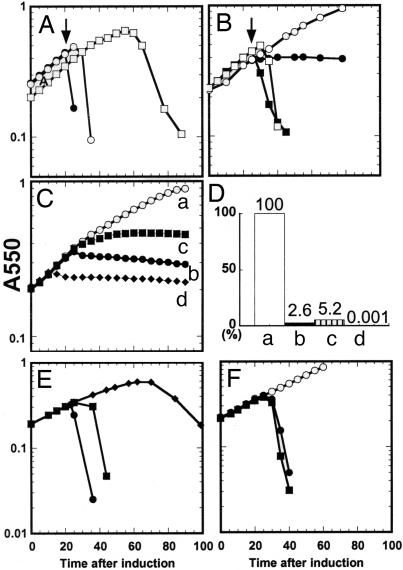

Fig. 3.

The TMDs of S2168 have opposing functions. In each experiment, cultures of MG1655 lacIq1 tonA::Tn10 bearing a plasmid carrying the indicated S21 and R21 alleles under the control of the λ late promoter, pR′, and a compatible transactivating plasmid, pQ, carrying the λ late-activator gene Q under the control of a hybrid lac-ara promoter (see SI Table 1). The cultures were induced at time 0, and turbidity was followed as a function of time. Constructs used in A, B, E, and F contained the wild-type R21 gene, whereas those used in C carried, instead, R21E35Q, encoding an enzymatically inactive form of R21. (A) Expression of S2168 in combination with R21 results in abrupt host lysis. (●, ○), S2168 R21; ♦, S2168 amR21. DNP was added (arrow) to one culture (●) at 20 min after induction. (B) Expression of S2168ΔTMD1 in combination with R21 results in abrupt host lysis. (●, ○), vector control; (■, □), S2168ΔTMD1 R21; DNP was added (arrows) to two of the cultures (■, ○) at 25 min after induction. (C and D) Induction of different S2168 alleles in the absence of endolysin causes lethality. C shows growth curves after induction: (○, curve a), vector control; (■, curve b), S2168; (■, curve c), S2168ΔTMD1; (♦, curve d), ssphoAΦS2168. D shows cell survival at 60 min after induction, assessed as colony forming units (CFU) and expressed as a percentage of the control. (E) TMD1 of S2168 antagonizes the holin activity of its TMD2. (●), S2168 R21; (■), S2168S16C R21; (♦), RYIRSΦS2168S16C R21. (F) The SAR domain of P1 Lyz cannot inhibit hole formation by TMD2 of S2168. (○), SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1, uninduced; (●), SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1, induced; (■), RYIRS-SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1, induced.

Does TMD1 Exit the Bilayer?

To provide biochemical evidence that TMD1 of nascent, membrane-inserted S2168 leaves the bilayer, we altered the S21 gene so that codon 16 encodes Cys rather than Ser (Fig. 1A). Our rationale was that disulfide-linked dimers might form if oligomerization of the holin in the membrane brought the TMD1 segments from many S2168 molecules into close proximity in the oxidizing environment of the periplasm. Induction of the S2168S16C missense allele in the presence of R21 resulted in abrupt lysis of the host, indicating that the S16C protein is fully functional as a holin (Fig. 3E). The fact that the S2168S16C allele triggers 5–10 min later than the wild type is not unexpected, given the wide range of lysis times seen with a collection of single missense mutants in the holin of bacteriophage λ (10). When membranes of cells expressing the S2168S16C allele were examined by SDS/PAGE under nonreducing conditions, a dimeric species was identified by Western blot analysis (Fig. 2B). Moving the Cys residue to the opposite face of the putative TMD1 helix eliminated the dimer (Fig. 2C), suggesting that its formation is due to specific TMD1–TMD1 interhelical interactions. We next inserted an oligonucleotide sequence encoding the epitope RYIRS after the start codon of S2168S16C (Fig. 1A). The presence of the additional positive charges provided by this epitope at the N terminus of S2168 should prevent its TMD1 from leaving the membrane. The RYIRS-tagged protein ran as a monomer under both reducing and nonreducing conditions (Fig. 2B), consistent with the retention of its TMD1 in the membrane.

Additional support for our contention that TMD1 of S21 moves from the membrane to the periplasm was obtained by examining the protease sensitivities of the S2168S16C and RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C in spheroplasts. Upon exposure to proteinase K, the majority of the S2168S16C dimer was converted to a form that migrated between the dimer and monomer positions when analyzed by nonreducing SDS/PAGE (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 4 and 5). The mobility of this cleavage product increased upon reduction, indicating the presence of a disulfide bond (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 3 and 5). Moreover, the small amount of monomer present was also converted into a form that had a slightly faster mobility. Because the Western blot was developed with antibodies raised to a peptide corresponding to the C-terminal 13 residues of S21, the bands visualized must have resulted from cleavage between the N terminus and Cys-16 and, thus, within TMD1. The RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C protein was found to be protease resistant (Fig. 2D, compare lanes 7 and 8). The different protease sensitivity of TMD1 in S2168 and the RYIRS-tagged protein supports our interpretation that the former is exposed to the aqueous environment, whereas the latter remains embedded in the membrane.

Membrane-Inserted TMD1 Specifically Inhibits Hole Formation by TMD2.

Surprisingly, cells induced to synthesize the RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C grew well past the time of triggering for S2168S16C (Fig. 3E), suggesting that the presence of TMD1 of S2168 in the membrane blocks lesion formation by TMD2. To show that this inhibitory effect was specific, we replaced TMD1 of S2168 with the SAR domain of Lyz (Fig. 1A). The chimeric protein SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1 retained its holin function although triggering was delayed ≈5 min when compared with S2168 (Fig. 3F). Unlike the case of S2168, attaching the RYIRS tag to the N terminus of the SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1 protein did not alter the triggering time of the chimera (Fig. 3F). Thus, the inhibition of hole formation is specific for the SAR domain of S21 and is not observed with a heterologous SAR domain. Further support for the idea that TMD1 serves physiologically as an inhibitor of hole formation was obtained by fusing the cleavable signal sequence from the periplasmic enzyme alkaline phosphatase (PhoA) to the N terminus of S2168 (Fig. 1A). Expression of this construct, ssphoAΦS2168, was lethal much earlier than with wild type S2168 (Fig. 3 C and D). SDS/PAGE and Western blotting showed that the chimeric protein had been processed by signal peptidase and migrated identically to S2168 (SI Fig. 6). We suspect that the early lethality of the ssPhoAΦS2168 protein is because of the fact that the SAR domain that constitutes TMD1 of S2168 was exported directly to the periplasm and never resided in the membrane (see below).

Exit of TMD1 from the Membrane Coincides with Holin Triggering.

Finally, to demonstrate that TMD1 of the S21 gene products spends a discrete period in the inner membrane before its release to the periplasm, we followed the change in the monomer/dimer ratio for the S16C alleles of S2168 and also for S2171, an allele that produces only the antiholin (Fig. 1C; see Materials and Methods), as a function of time. As can be seen in Fig. 2E, the relative amount of the dimeric species increased with time for both proteins, although somewhat more rapidly for S2168S16C than for S2171S16C (SI Fig. 7). With ssPhoAΦS2168S16C, where a secretory signal sequence directly effects export of TMD1, the kinetics of disulfide bond formation is accelerated (Fig. 2, compare E with F; also, see SI Fig. 7), as is the kinetics of triggering (Fig. 3C). Moreover, artificially triggering either the holin or the antiholin by the addition of the uncoupler, DNP, resulted in a rapid and dramatic increase in the amount of dimerized S21 (Fig. 2G).

Previously, we had reported that although S2171 acted as an antiholin, it caused only a slight delay in cell lysis when coexpressed with S2168 (15). This observation can now be explained by the fact that TMD1 of S2171 enters the periplasm, an event that converts the antiholin into a topological isomer with holin activity. Therefore, we would predict that the RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C protein would be a much more robust antiholin than S2171. In fact, when RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C was coexpressed with S2168 holin, triggering did not occur for well over 1 h after induction (SI Fig. 8). Thus, not only does TMD1 antagonize the hole-forming activity of TMD2 when they are part of the same molecule, but S21 molecules with both TMDs in the membrane can act in trans to block hole formation by other S21 molecules.

Discussion

Topological Differences Between the S21 Holin and Antiholin.

The S21 gene encodes two proteins with two predicted TMDs; S2168, a holin, and S2171, an antiholin. TMD1 of S21 is enriched for small, nonpolar (Ala, Gly) and polar, uncharged (Thr, Ser) residues, a feature unusual for canonical TMDs but common to the established SAR domains of the bacteriophage endolysins Lyz and R21 (7). The N-terminal SAR domains of the latter proteins facilitate their secretion to the periplasm where they remain tethered to the cytoplasmic membrane by their SAR helices. Subsequently, their SAR domains exit the membrane, thereby releasing active endolysin to the periplasm (7). If the S21 TMD1 behaved as a SAR domain, then the S21 holin would have one fewer TMDs than its antiholin (Fig. 1B).

Several lines of evidence support this model. First, and most surprising, deletion of TMD1 from S2168 did not abolish its holin function but only delayed its triggering time by ≈5 min (Fig. 3 compare A with B), making S2168ΔTMD1, at 44 residues, the smallest polypeptide known to exhibit the essential properties of a holin. Second, whereas its deformylated state places the N terminus of nascent S21 in the cytoplasm, both the propensity of S2168S16C to form disufide-linked dimers (Fig. 2B) and the protease sensitivity of the dimers in spheroplasts (Fig. 2D) places TMD1 in the periplasm. Moreover, although most of either S2168S16C or S2171S16C protein exists as a monomer shortly after induction, the proportion that exists as a dimer increases with time (Fig. 2E). Dimer formation occurs most rapidly with S2168S16C, perhaps because of the extra positively charged residue at the N terminus of S2171S16C that serves to impede the release of its TMD1 to the periplasm. A critical prediction of our model is that treatments known to artificially trigger S21 should result in a rapid increase in the amount of dimer. Indeed, the addition of DNP to cultures induced for either protein increased the amount of dimer. Significantly, the conversion of S2168S16C monomer to dimer was immediate and nearly complete (compare lanes 2 and 3 of Fig. 2G), a strong argument in favor of the hypothesis that the rate at which the S21 dimers appear reflects the rate at which the membrane-embedded TMD1 enters the periplasm. These experiments indicate that TMD1 of both S2168 and S2171 is initially inserted into the cytoplasmic membrane and is subsequently released to the periplasm.

Role of TMD1 in Holin Triggering.

Because TMD1 is not essential for the holin function of S2168, what, then, is its function? The behavior of the RYIRS-tagged S2168S16C protein suggests an answer to this question. SDS/PAGE and Western blotting showed that, although the tagged protein was present at normal levels, the disulfide-linked dimer was notably missing (Fig. 2B). We interpret this fact to mean that the additional positive charges provided by the RYIRS tag prevent the movement of TMD1 from the membrane to the periplasm. Significantly, cells producing this protein grew well beyond the point at which lysis would have occurred because of the induction of S2168S16C (Fig. 3E). Thus, the continued presence of TMD1 in the membrane was antagonistic toward the lesion-forming activity of TMD2.

Model for the Function of S21.

Both of the S21 TMDs have potential GxxxG-like motifs (Figs. 1A and 4A) that might serve as the basis for homotypic and/or heterotypic helix interactions (19). GxxxG-like motifs have been implicated in such interactions between transmembrane helices by facilitating the intimate approach of the polypeptide backbones and the formation of H bonds between αH atoms and backbone carbonyls (20, 21). For TMD1, these motifs provide a glycine-rich surface that may be important for interhelix packing, particularly in the periplasm. For the TMD2 helix, the contact surface defined by its two overlapping GxxxG-like motifs is coincident with its single hydrophilic surface (Fig. 4A) which could line the “hole” formed by S21 after triggering.

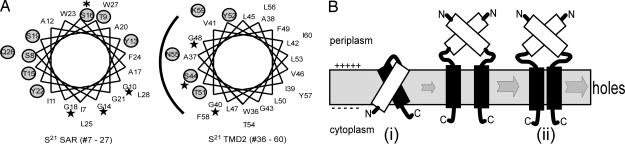

Fig. 4.

Potential homotypic and heterotypic TMD interactions in the function of S21. (A) Helical projections of TMDs of S21. Stars indicate GxxxGxxxG-like motifs of each TMD (G10, G14, and G18 in TMD1; G40, S44, and G48 in TMD2). Hydrophilic or neutral residues in each TMD are circled and shaded. (Left) the SAR domain (TMD1) of S21 (residues 7–27), with the position of the S16C mutation highlighted by an asterisk. (Right) TMD2, the hole-forming domain of S21 (residues 36–60), with a potential hydrophilic surface that may line the lethal membrane lesion indicated by the arc. (B) Pathway to hole formation involves inhibited (i) and active (ii) topological isomers of S21. See Discussion for details.

Our model for hole formation by S21 is depicted in Fig. 4B. Initially, S21 is inserted into the cytoplasmic membrane as a helical hairpin with predominant TMD1–TMD2 interactions. These interactions either mask the hydrophilic surface of TMD2 or prevent the self-association of TMD2 and serve to block hole formation. Upon triggering, TMD1 exits the membrane for the periplasm, allowing oligomerization of S21 through homotypic TMD2–TMD2 interactions within the bilayer, a process that might be facilitated by homotypic TMD1–TMD1 interactions in the periplasm. By this reasoning, the delayed triggering of S2168ΔTMD1 (Fig. 3B) and SARlyzΦS2168ΔTMD1 (Fig. 3F) would be due to the absence of the periplasmic TMD1 interactions. The antiholin activity of S2171 is due to the extra positive charge at its N terminus (Fig. 1) that delays the exit of its TMD1 from the membrane, compared with S2168. The presence of significant levels of S2171 in its helical hairpin configuration with interacting TMDs would “poison” the oligomerization of S2168 into functional holes.

There are many issues of interest that arise from this perspective. First, it is not clear what allows a SAR domain to escape from the membrane in a potential-dependent manner. Also, neither for Sλ nor for S21 is it understood what constitutes the timing mechanism that allows holins to impose a specific temporal program on the infective cycle. Our model for S21 predicts that the escape of TMD1 is necessary for holin triggering, but it is clearly not sufficient. Even the S2168ΔTMD1 deletion protein, lacking the inhibitory TMD1, still has a defined triggering time. And, finally, it is unclear how the timing mechanism of either holin is subverted by deenergization of the membrane.

Materials and Methods

General Methods.

Bacterial culture conditions, induction and monitoring of lysis kinetics are described in SI Supporting Materials and Methods. All experiments were done with a lacIq1 tonA::Tn10 derivative of MG1655, the sequenced wild-type strain of Escherichia coli K-12 (22). For most experiments, the bacterial strains carried two plasmids, a low-copy plasmid pQ, carrying the gene for the λ late gene activator, Q, under Plac/ara-1 control, and a medium-copy plasmid with a pBR322 origin and the lysis gene cassette, SRRzRz1, under the control of the late promoter, pR′ (14). The lysis gene cassettes were from either λ or phage 21, as indicated. Induction of the lysis genes was accomplished by adding 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside (IPTG) to the culture. In experiments where the wild type or modified alleles of P1 lyz were induced, the only plasmid present was a derivative of pJF118, a medium-copy plasmid carrying the lyz allele under control of the tac promoter (7). The important features of these plasmids and details of the constructions can be found in SI Table 1 and Supporting Materials and Methods.

Subcellular Fractionation.

Subcellular fractionation has been described (7) (see SI Supporting Materials and Methods for a summary). As controls, Rλ, the endolysin encoded by bacteriophage λ, was used for the soluble and spheroplast fraction, FtsIcmyc was used for the membrane fraction, and PhoA was used for the periplasmic fraction (SI Figs. 5 and 6). In general, control samples were prepared in parallel to the experimental samples.

Protein Expression in Spheroplasts and Proteinase K Digestion.

Spheroplasts carrying the indicated plasmids were suspended in 0.5× LB medium containing 12.5% sucrose, induced with 1 mM IPTG and 0.2% arabinose, and incubated without shaking for 25 min at 37°C. Aliquots (1.5 ml) containing ≈4 × 108 spheroplasts were treated with proteinase K (20 μg/ml final concentration) for the indicated times at room temperature. Proteinase K treatments were stopped by adding trichloroacetic acid (TCA), as described below.

SDS/PAGE and Western Blotting.

SDS/PAGE and Western blotting were performed as described (23), except that Tris–Tricine SDS/PAGE (24) was used for detection of proteinase K degradation products. Antibody against the peptide KIREDRRKAARGE, which corresponds to the S21 C terminus, was raised in rabbits (15). Proteins tagged with the cmyc epitope were detected by using a mouse monoclonal antibody from Babco (Richmond, CA). Antibody against the purified His6-tagged Lyz was prepared in chickens by Aves Labs, (Tigard, OR). HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies against chicken IgY, mouse IgG, and rabbit IgG were from Aves Labs, Pierce (Rockland, IL), and Pierce, respectively. Generally, primary antibodies were used at a 1:1,000 dilution, whereas secondary antibodies were used at a 1:3,000 dilution. In some experiments, the primary antibody was preabsorbed with a lysate of E. coli MG1655, which accounts for the absence of the background band just above the S21 dimer band in Fig 2. C–G.

Blots were developed by using the chromogenic substrate 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Equivalent sample loadings were used whenever multiple fractions obtained from the same culture were analyzed. For Fig. 2D, the Vectastain ABC-AmP kit from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA) was used for detection of proteins on the blot. Different background bands were routinely observed when compared with the HRP-conjugated secondary antibody obtained from Pierce.

To show the presence of disulfide-linked dimers of the cysteine-containing derivatives of S21, culture aliquots were adjusted to 10% TCA and placed on ice for 30 min. The precipitate was collected by centrifugation and washed with acetone to remove the TCA. Pellets were air dried and resuspended in SDS/PAGE loading buffer with, or without reducing agent as indicated.

Purification and N-Terminal Sequencing of S2168.

S2168his was purified from an induced culture of E. coli BL21(DE3) cells carrying the plasmid pETS2168his (SI Supporting Materials and Methods) by immobilized metal ion-affinity chromatography, as described (25, 26). Samples containing ≈100 μg of S2168his were subjected to SDS/PAGE, and the separated proteins were electroblotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride paper (PVDF; Millipore, Bedford, MA). The region of the blot corresponding to the S2168his protein was excised, and the bound protein was subjected to automated N-terminal sequencing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The clerical assistance of Daisy Wilbert and the suggestions of the entire Young laboratory are gratefully acknowledged. Protein sequencing services were provided by L. Dangott of the Protein Chemistry Laboratory. This work was supported by Public Health Service Grant GM27099 (to R.Y.), the Robert A. Welch Foundation, and the Program for Membrane Structure and Function at Texas A&M University.

Abbreviations

- DNP

dinitrophenol

- TCA

trichloroacetic acid

- TMD

transmembrane domain.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS direct submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0604444103/DC1.

References

- 1.Fuhrman JA. Nature. 1999;399:541–548. doi: 10.1038/21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hendrix RW, Smith MC, Burns RN, Ford ME, Hatfull GF. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2192–2197. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Young R, Wang IN, Roof WD. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8:120–128. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(00)01705-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young R. Microbiol Rev. 1992;56:430–481. doi: 10.1128/mr.56.3.430-481.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gründling A, Manson MD, Young R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9348–9352. doi: 10.1073/pnas.151247598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang IN, Smith DL, Young R. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2000;54:799–825. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.54.1.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu M, Struck DK, Deaton J, Wang IN, Young R. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:6415–6420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400957101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xu M, Arulandu A, Struck DK, Swanson S, Sacchettini JC, Young R. Science. 2005;307:113–117. doi: 10.1126/science.1105143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young R. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;4:21–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raab R, Neal G, Sohaskey C, Smith J, Young R. J Mol Biol. 1988;199:95–105. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(88)90381-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bläsi U, Nam K, Hartz D, Gold L, Young R. EMBO J. 1989;8:3501–3510. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1989.tb08515.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bläsi U, Chang C-Y, Zagotta MT, Nam K, Young R. EMBO J. 1990;9:981–989. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08200.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graschopf A, Bläsi U. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:569–582. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gründling A, Smith DL, Bläsi U, Young R. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:6075–6081. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.21.6075-6081.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barenboim M, Chang C-Y, dib Hajj F, Young R. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:715–727. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01385.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bonovich MT, Young R. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:2897–2905. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.9.2897-2905.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sonnhammer EL, von Heijne G, Krogh A. Proc Sixth Int Conf Intelligent Systems Mol Biol. 1998;6:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.von Heijne G. Nature. 1989;341:456–458. doi: 10.1038/341456a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Senes A, Engel DE, DeGrado WF. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2004;14:465–479. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Senes A, Gerstein M, Engelman DM. J Mol Biol. 2000;296:921–936. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Senes A, Ubarretxena-Belandia I, Engelman DM. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:9056–9061. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161280798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guyer MS, Reed RR, Steitz JA, Low KB. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1981:135–140. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1981.045.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gründling A, Bläsi U, Young R. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:769–776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schägger H, von Jagow G. Anal Biochem. 1987;166:368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith DL, Chang C-Y, Young R. Gene Expr. 1998;7:39–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deaton J, Savva CG, Sun J, Holzenburg A, Berry J, Young R. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1778–1786. doi: 10.1110/ps.04735104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inouye H, Barnes W, Beckwith J. J Bacteriol. 1982;149:434–439. doi: 10.1128/jb.149.2.434-439.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graschopf A, Bläsi U. Arch Microbiol. 1999;172:31–39. doi: 10.1007/s002030050736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.