Abstract

Background: Improved hygiene in Westernised regions of the world may be partly responsible for the increased prevalence of diseases of the immune system, such as asthma and atopy. There is a paucity of data on cleanliness norms in young children in the UK and there has been no attempt to identify factors that influence the adoption of particular hygiene practices in the home.

Aims: To examine levels of hygiene in a contemporary cohort of children and identify social and lifestyle factors influencing hygiene practices in the home.

Methods: The sample under study are participants in the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC). Parental self completion questionnaires provided data on hygiene levels in children at 15 months of age, and a hygiene score was derived from these responses. Multivariable logistic regression models investigated associations between high hygiene scores (top quintile) and a number of perinatal, maternal, social, and environmental factors.

Results: Maternal smoking during pregnancy, low maternal educational achievement, and living in local authority housing were factors independently associated with high hygiene scores, as was increased use of chemical household products. High hygiene scores were inversely related to living in damp housing and attendance at day care. There were no gender or ethnic differences in hygiene score.

Conclusion: Important data on cleanliness norms for infants have been presented. The adoption of hygiene practices is influenced to some degree by social, lifestyle, and environmental factors—with higher hygiene scores occurring in more socially disadvantaged groups. Increased use of chemical household products in the more socially disadvantaged groups within ALSPAC has emerged as an important confounder in any study of hygiene and ill health.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (145.7 KB).

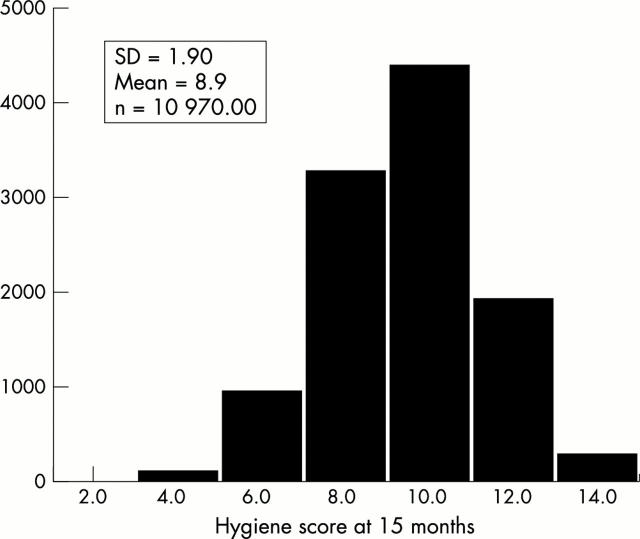

Figure 1 .

Hygiene score at 15 months.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Becher R., Hongslo J. K., Jantunen M. J., Dybing E. Environmental chemicals relevant for respiratory hypersensitivity: the indoor environment. Toxicol Lett. 1996 Aug;86(2-3):155–162. doi: 10.1016/0378-4274(96)03685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burney P. G., Chinn S., Rona R. J. Has the prevalence of asthma increased in children? Evidence from the national study of health and growth 1973-86. BMJ. 1990 May 19;300(6735):1306–1310. doi: 10.1136/bmj.300.6735.1306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr M. L., Butland B. K., King S., Vaughan-Williams E. Changes in asthma prevalence: two surveys 15 years apart. Arch Dis Child. 1989 Oct;64(10):1452–1456. doi: 10.1136/adc.64.10.1452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collet J. P., Burtin P., Floret D. Risque infectieux chez l'enfant en crèche. Rev Prat. 1992 Sep 15;42(14):1797–1803. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewey C., Midgeley E., Maw R. The relationship between otitis media with effusion and contact with other children in a british cohort studied from 8 months to 3 1/2 years. The ALSPAC Study Team. Avon Longitudinal Study of Pregnancy and Childhood. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2000 Sep 15;55(1):33–45. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5876(00)00377-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatherer A. A review of standards of infant hygiene in the home. Nurs Times. 1978 Oct 12;74(41):1684–1685. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manun'Ebo M., Cousens S., Haggerty P., Kalengaie M., Ashworth A., Kirkwood B. Measuring hygiene practices: a comparison of questionnaires with direct observations in rural Zaïre. Trop Med Int Health. 1997 Nov;2(11):1015–1021. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez F. D., Cline M., Burrows B. Increased incidence of asthma in children of smoking mothers. Pediatrics. 1992 Jan;89(1):21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Openshaw P. J., Walzl G. Infections prevent the development of asthma--true, false or both? J R Soc Med. 1999 Oct;92(10):495–499. doi: 10.1177/014107689909201001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osterholm M. T., Reves R. R., Murph J. R., Pickering L. K. Infectious diseases and child day care. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1992 Aug;11(8 Suppl):S31–S41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peat J. K., van den Berg R. H., Green W. F., Mellis C. M., Leeder S. R., Woolcock A. J. Changing prevalence of asthma in Australian children. BMJ. 1994 Jun 18;308(6944):1591–1596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.308.6944.1591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strachan D. P. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989 Nov 18;299(6710):1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariq S. M., Matthews S. M., Hakim E. A., Stevens M., Arshad S. H., Hide D. W. The prevalence of and risk factors for atopy in early childhood: a whole population birth cohort study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1998 May;101(5):587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0091-6749(98)70164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towns S., Wong M. Assessment of the child with recurrent respiratory infections. Aust Fam Physician. 2000 Aug;29(8):741–746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Mutius E., Martinez F. D., Fritzsch C., Nicolai T., Roell G., Thiemann H. H. Prevalence of asthma and atopy in two areas of West and East Germany. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994 Feb;149(2 Pt 1):358–364. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.2.8306030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]