Abstract

In a previous study, we reported an antileukaemic activity of auranofin (AF), demonstrating its dual effects: on the induction of apoptotic cell death and its synergistic action with retinoic acid on cell differentiation. In this study, we investigated the downstream signalling events of AF-induced apoptosis to determine the molecular mechanisms of AF activity.

Treatment of HL-60 cells with AF induced apoptosis in a concentration- and time-dependent manner. Western blot analysis showed that AF-induced apoptosis was accompanied by the activation of caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3, and the release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria.

The phosphorylation and kinase activities of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38 MAPK) increased gradually until 12 h after AF (2 μM) treatment, and p38 MAPK was also activated concentration-dependently. Pretreatment with SB203580, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK, significantly blocked DNA fragmentation and the cleavage of procaspase-8, procaspase-3, and poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP), whereas SB203580 alone had no effect.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) were also detected within 1 h after AF treatment, and the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) effectively protected the cells from apoptosis by inhibiting the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and the activation of caspases.

These results suggest that ROS generation and the subsequent activation of p38 MAPK are essential for the proapoptotic effects of AF in human promyelocytic leukaemia HL-60 cells.

Keywords: Apoptosis, auranofin, p38 MAPK, reactive oxygen species, HL-60 cell line

Introduction

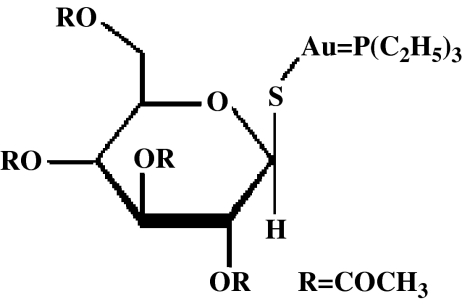

Auranofin (AF; 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-D-glucopyranosato-S-[triethyl phosphine] gold) is a lipophilic gold complex (Figure 1) that reduces the gene expression of proinflammatory cytokines through the inhibition of NF-κB activation (Yamada et al., 1999; Jeon et al., 2000, 2003). Owing to its anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive properties, AF has been widely used as an antirheumatic drug (Snyder et al., 1987; Borg et al., 1988; Hashimoto et al., 1992).

Figure 1.

The structure of AF.

As it reacts with thiol and/or selenol groups, AF also acts as a potent and specific inhibitor of mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase (TrxR), which is a selenocysteine-containing enzyme (Gromer et al., 1998). TrxR catalyses the NADPH-dependent reduction of thioredoxin (Trx), which plays a role in maintaining the cellular redox state (Mustacich & Powis, 2000). Recently, it was reported that AF inhibits mitochondrial TrxR and induces a mitochondrial permeability transition (Rigobello et al., 2002). As a result, cytochrome c is released into the cytoplasm (McKeage, 2002; Rigobello et al., 2004). It is well known that cytochrome c released from the mitochondria participates in the formation of apoptosomes and ultimately leads to apoptotic cell death (Green, 1998). Therefore, this raises the possibility that AF could be utilized as an anticancer drug to induce the apoptotic cell death of malignant cells by inhibiting mitochondrial TrxR.

Until now, the focus of AF as an antirheumatic drug has been on its anti-inflammatory properties. However, we have found that AF exhibits an antileukaemic effect. This drug not only induces apoptotic cell death but also synergistically enhances the differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia (APL) cells in a combined treatment with retinoic acid (Kim et al., 2004). Our previous report demonstrated that AF induces caspase-3-dependent apoptotic cell death via the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), although the detailed mechanism by which AF initiates apoptosis remains poorly understood.

ROS are recognized as a mediator of apoptotic cell death, playing pivotal roles in the relevant signalling pathways. One of the most important signal molecules in ROS-mediated apoptosis is mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), a family of serine/threonine kinases. The MAPK superfamily consists of at least three major groups: extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK1/2), c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase/stress-activated protein kinase (JNK/SAPK), and p38 MAPK (Cobb, 1999). ERK1/2, which are activated by growth factors and are critically involved in mitogenesis, were inhibited in ajoene-induced HL-60 cell death (Antlsperger et al., 2003). JNK/SAPK and p38 MAPK, which are activated by a variety of cellular stresses and inflammatory cytokines, were involved in APL cell apoptosis induced by arsenic trioxide and zinc, respectively (Kondoh et al., 2002; Davison et al., 2004).

To determine the signal pathway of apoptotic cell death stimulated by AF, we investigated the effect of AF on the regulation of MAPKs using the human APL cell line HL-60 and found that the activation of p38 MAPK is associated with AF-induced apoptosis. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of AF activity associated with MAPK signalling.

Methods

Cell culture and treatment

HL-60 cells were cultured (37°C, 5% CO2) in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated foetal bovine serum. To induce apoptosis, the cells were incubated at a density of 5 × 105 ml−1 in fresh medium containing 2 μM AF for the indicated periods.

Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation assay

The procedure for analysing internucleosomal DNA fragmentation was performed as reported previously, with minor modifications (Whitman et al., 1997). Briefly, AF-treated HL-60 cells were harvested and washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, 20 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 0.1% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.4) and left to stand for 20 min at room temperature. The lysates were serially incubated with DNase-free RNase A (0.1 mg ml−1) for 30 min at 37°C, and with proteinase K (0.5 mg ml−1) for 16 h at 55°C. The DNA was then extracted with an equal volume of phenol : chloroform : isoamyl alcohol (25 : 24 : 1) and dissolved in deionized water. Equal amounts of the DNA samples were then fractionated by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, stained with ethidium bromide, and visualized with UV illumination.

Quantification of apoptotic cells

Apoptotic cell death was quantified using flow-cytometric analysis of propidium-iodide-stained nuclei. The cells were incubated with AF for the indicated times, washed twice with PBS, fixed in cold 70% ethanol, and stored overnight at 4°C. After the ethanol was removed, the cells (1 × 106) were washed and resuspended in 1 ml of PBS containing DNase-free RNase A (10 mg ml−1) and propidium iodide (50 μg ml−1). After agitation for 30 min at room temperature, the amount of propidium iodide incorporated was determined using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur with CellQuest software; Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany).

Western blot analysis

The cells were washed twice with PBS and then lysed in lysis buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 0.1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin, and 5 μg ml−1 leupeptin) for 20 min on ice. Equal amounts of cell lysate proteins were separated on 12% SDS–polyacrylamide gel, transferred to nitrocellulose membrane, and analysed with various human antibodies. Anti-caspase-8, -caspase-9, -caspase-3, and -poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) antibodies, as well as anti-p38 MAPK and anti-phospho-p38 antibodies, were used as primary antibodies. Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG was used as the secondary antibody. The proteins of interest were visualized using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit. When p38 MAPK was analysed the cells were preincubated overnight in serum-free RPMI 1640 medium to remove any serum effects. For the p38 MAPK inhibition assay, a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK, SB203580 (20 μM), was added to the culture 30 min before AF treatment.

In vitro kinase assay

p38 kinase activity was determined using a p38 MAP kinase assay kit, according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. Briefly, the cells were cultured overnight, at a density of 5 × 105 ml−1 in RPMI 1640 medium without foetal bovine serum, and treated the next day with AF for 1, 3, 6, or 12 h. The cells were harvested and lysed in ice-cold cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg ml−1 leupeptin, and 1 mM phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride). Immobilized monoclonal antibody (20 μl) directed against phospho-p38 MAPK (Thr180/Tyr182) was added to an aliquot (200 μl) of cell lysate that contained approximately 200 μg of total protein, and incubated overnight at 4°C with gentle rocking. The immunoprecipitated pellet was washed twice with kinase buffer (25 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 5 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 2 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.1 mM Na3VO4, and 10 mM MgCl2), resuspended in 50 μl of kinase buffer supplemented with 200 μM ATP and 2 μg of activating transcription factor (ATF)-2 fusion protein, and incubated at 30°C for 30 min. The reaction was terminated by the addition of 25 μl of 3 × electrophoresis sample buffer. The samples were boiled for 5 min and loaded onto an SDS–polyacrylamide gel. The phosphorylated ATF-2 protein was subsequently analysed by Western blots probed with anti-phospho-ATF-2 antibody.

Measurement of cytochrome c release

Cytochrome c release was measured using a cytochrome c release apoptosis assay kit, according to the procedure recommended by the manufacturer. After washing with ice-cold PBS, the cells (5 × 106) were suspended in cytosol extraction buffer mix containing DTT and protease inhibitors, incubated on ice for 10 min, homogenized on ice with 30–50 strokes using a tissue grinder, and centrifuged at 700 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube and centrifuged again at 10,000 × g for 30 min. The supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction and the resulting mitochondria pellets were dissolved in mitochondria extraction buffer mix containing DTT and protease inhibitors. Equal amounts of cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions isolated from the cells were loaded onto a SDS–15% polyacrylamide gel. A standard Western blotting procedure was performed and the blot probed with anti-cytochrome c antibody.

Intracellular ROS determination

Intracellular ROS were detected by flow cytometry using 2′,7′-dichlorohydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA). This compound is deacetylated by intracellular esterase and converted to nonfluorescent DCFH, which is oxidized to the fluorescent compound DCF in the presence of ROS. HL-60 cells were treated with or without 2 μM AF for 10, 30, or 60 min. Then 20 μM DCFH-DA was added to the AF-treated cells, which were further incubated for 30 min. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and analysed by measuring the fluorescence intensity (FL-1, 530 nm) of 104 cells using a flow cytometer (FACSCalibur with CellQuest software).

Statistical analysis

Student's t-test and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to determine the statistical significance of differences between values for various experimental and control groups. P-values <0.05 were considered significant.

Materials

The HL-60 cell line was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, U.S.A.), and AF was obtained from Yuhan Medica Corporation (Gunpo, Korea). RPMI 1640 medium, proteinase K, propidium iodine, Nonidet P-40, sodium deoxycholate, phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, trypsin inhibitor, leupeptin, and aprotinin were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). DNase-free RNase A and foetal bovine serum were obtained from Boehringer Mannheim (Mannheim, Germany) and HyClone (Logan, UT, U.S.A.), respectively. Antibodies directed against caspase-8, caspase-9, caspase-3, and PARP were purchased from Pharmingen (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), and SB203580 was from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany). Anti-MAPK (p38, JNK, and ERK) antibodies, anti-phospho-MAPK antibodies, and the p38 MAP kinase assay kit were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA, U.S.A.). The enhanced chemiluminescence detection kit and cytochrome c release apoptosis assay kit were from Amersham–Pharmacia Biotech, Inc. (Piscataway, NJ, U.S.A.) and OncogeneTM Research Products (San Diego, CA, U.S.A.), respectively. All other chemicals used in the study were of molecular biology grade.

Results

Induction of apoptosis by AF in HL-60 cells

Our previous report revealed that AF exerts an antileukaemic effect by acting on both apoptotic cell death and the differentiation of the NB4 APL cell line (Kim et al., 2004). APL is a promyelocytic leukaemia caused by a failure in progenitor cell differentiation towards mature cells. The promyelocytic leukaemia–retinoic acid receptor alpha (PML–RARα) fusion protein, which results from a reciprocal chromosomal translocation (t[15;17]), plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of APL (Grignani et al., 1994; Mistry et al., 2003). To investigate whether AF activity in apoptotic cell death is limited to leukaemia cells expressing the PML–RARα fusion protein, we tested HL-60 promyelocytic leukaemia cells in which the PML–RARα fusion protein is absent.

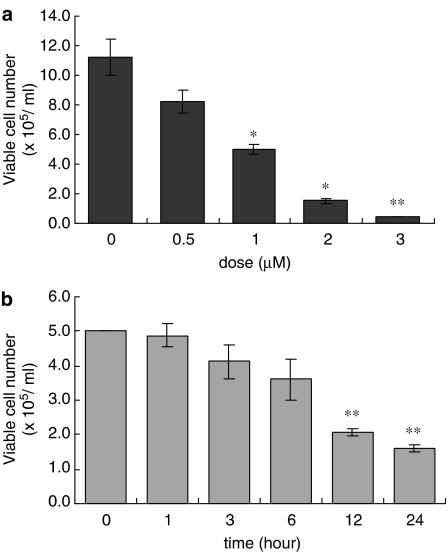

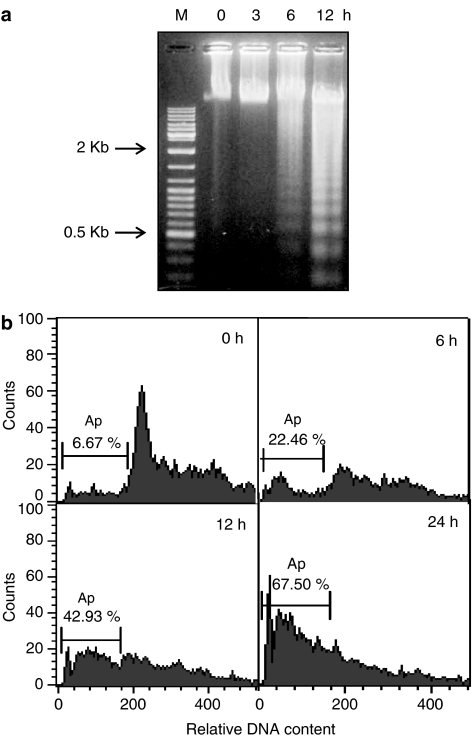

When HL-60 cells were treated with AF, cell viability was diminished concentration- and time-dependently (Figure 2a and b). To confirm whether cell death was caused by apoptotic processes, we assessed the DNA fragmentation in cells incubated with 2 μM AF for the indicated times. DNA laddering on an agarose gel was observed in cells treated with AF for more than 6 h (Figure 3a). On flow cytometry, the percentages of apoptotic cells were 22.46, 42.93, and 67.50% at 6, 12, and 24 h after treatment, respectively, when cells appearing as sub-G0/G1 were scored as the apoptotic cell population (Figure 3b). The induction of DNA laddering and the increased sub-G0/G1 peak indicate that AF also induces the apoptosis of myeloid leukaemia cells not containing the PML–RARα fusion protein.

Figure 2.

Time- and concentration-dependent induction of cell death by AF. HL-60 cells (5 × 105 ml−1) were incubated for 24 h in medium containing various concentrations of AF (0.5–3 μM) (a), and were incubated with 2 μM AF for 1–24 h (b). After incubation, the numbers of viable cells were counted with a haemocytometer. The data are represented as means±s.d. of triplicate experiments. *P<0.05 relative to an untreated group. **P<0.001 relative to an untreated group.

Figure 3.

Internucleosomal DNA fragmentation induced by AF in HL-60 cells. Cells (5 × 105 ml−1) were treated with 2 μM AF for the indicated periods. (a) Equal amounts of genomic DNA (10 μg) were analysed by 1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis and DNA laddering was visualized by staining the gel with ethidium bromide. DNA ladder mix was used as the molecular size marker. (b) FACS analysis of the propidium-iodide-stained cells was performed as described in Methods. Cells appearing in the sub-G0/G1 peak were scored as apoptotic cells. Data shown represent a typical result obtained from three (a) or two (b) independent experiments.

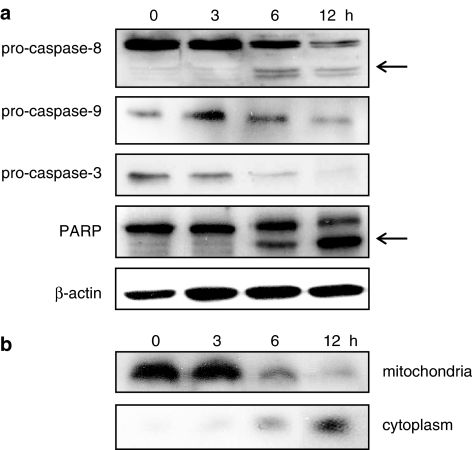

Activation of the caspase cascade and cytochrome c release during AF-induced apoptosis

To characterize the molecular events involved in AF-induced apoptosis, we first examined whether this apoptosis involved the activation of a caspase cascade. As shown in Figure 4a, the degradation of procaspase-8, procaspase-9, and procaspase-3 was observed 6 and 12 h after treatment with 2 μM AF. Consistently, incubation of HL-60 cells with AF cleaved the 116 kDa PARP protein, with the accumulation of the 89 kDa fragment (Figure 4a). β-Actin was used in the same experiment as the internal control.

Figure 4.

Activation of the caspase cascade and the release of cytochrome c during AF-induced cell death. (a) After treatment with 2 μM AF for the indicated times, cellular proteins were subjected to SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and the cleavage of procaspase-8, -9, and -3, and PARP was analysed by Western blotting probed with the appropriate antibodies. Arrows indicate the cleaved fragments. (b) After AF treatment, whole-cell lysates were further separated into the mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, and the fractions were analysed using an antibody directed against cytochrome c. The blots shown (a, b) are representative of three independent experiments.

To examine whether AF-mediated apoptosis acts via a mitochondria-dependent pathway, we measured the amount of cytoplasmic cytochrome c released from mitochondria. The amount of cytochrome c gradually increased in the cytoplasmic fraction during the apoptotic process, whereas it decreased in the mitochondrial fraction (Figure 4b).

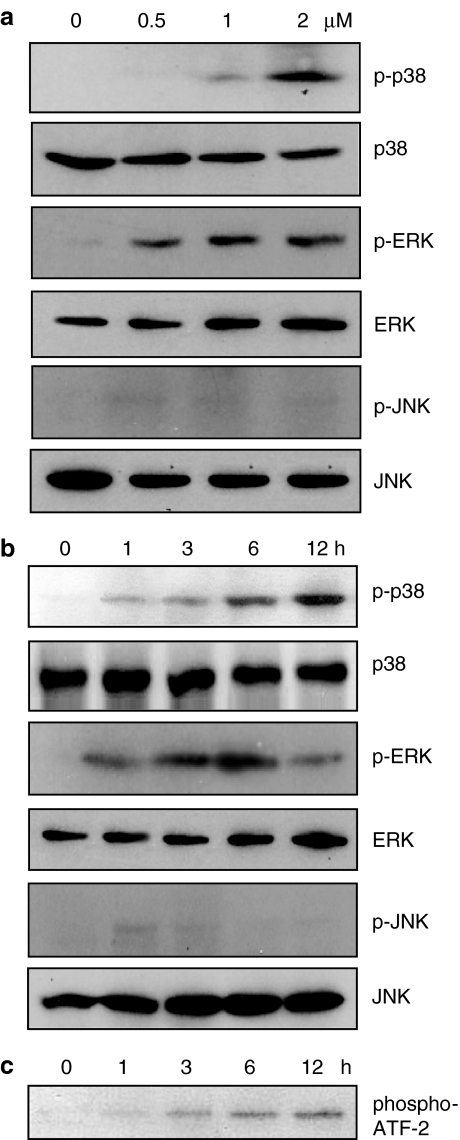

Involvement of p38 MAPK activation in AF-mediated apoptosis

Recent studies have suggested that apoptotic stimuli are transmitted to caspases through the activation of MAPKs, such as p38 MAPK and JNK (Huang et al., 1999; Kondoh et al., 2002). Therefore, we tested whether MAPK activation is involved in AF-induced apoptosis. Incubation of HL-60 cells with AF increased the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK in a concentration- and time-dependent manner (Figure 5a and b). The phosphorylation of p38 MAPK could be detected 1 h after treatment with 2 μM AF, and gradually increased until 12 h (Figure 5b). An in vitro kinase assay using ATF-2 as the exogenous substrate indicated that the kinase activity of p38 MAPK was also enhanced, consistent with the level of phosphorylated p38 (Figure 5b and c). As the amount of this protein was constant, as shown by Western blot analysis with anti-p38 antibody (Figure 5b), the increased phosphorylation of ATF-2 seemed to be due to the enhanced kinase activity of p38 MAPK, consistent with the increase in p38 phosphorylation. In contrast to the increase in p38 phosphorylation, no phosphorylation of JNK was induced. Phosphorylation of ERK was induced by AF but the level was constant, independent of AF dose and treatment time (Figure 5a and b). In addition, PD98059, an inhibitor of MEK, did not prevent the AF-induced apoptosis (data not shown). Therefore, it is likely that only the activation of p38 among the three MAPKs is associated with the proapoptotic effect of AF.

Figure 5.

Activation of MAPKs by AF treatment. HL-60 cells (5 × 105 ml−1) were incubated with 0, 0.5, 1, or 2 μM AF for 12 h (a), or were incubated with 2 μM AF for 0–12 h (b). Protein extracts were prepared at the indicated time points and analysed on Western blots probed with specific antibodies to ascertain the phosphorylation of MAPKs (p38, JNK, and ERK). (c) Cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with an anti-phospho-p38 antibody, and the immunoprecipitated proteins were subjected to an in vitro kinase assay, using ATF-2 as the exogenous substrate. The results shown (a–c) are representative of at least two independent experiments.

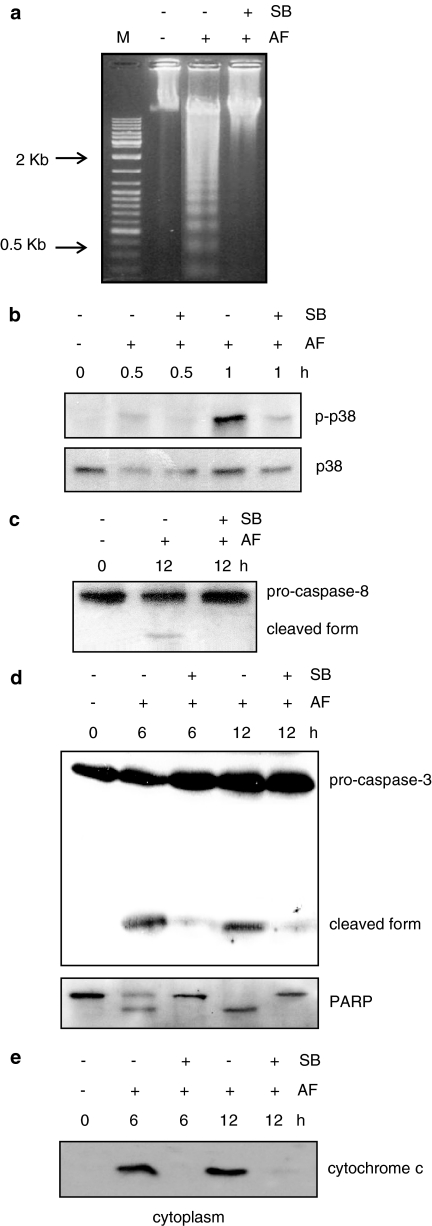

To confirm that the apoptosis induced by AF is transduced through the p38 MAPK pathway, the prevention of apoptosis by a specific inhibitor of p38 MAPK was examined. Preincubation of the cells with SB203580 for 30 min significantly blocked DNA fragmentation and the cleavage of procaspase-8, procaspase-3, and PARP, whereas SB203580 alone had no effect (Figure 6a–d). Furthermore, AF-stimulated cytochrome c release was also blocked by SB203580 pretreatment (Figure 6e).

Figure 6.

Involvement of p38 MAPK in AF-mediated apoptosis of HL-60 cells. Cells were preincubated with or without 20 μM SB203580 (SB) for 30 min before treatment with 2 μM AF. (a) At 12 h after AF treatment, the cells were harvested and internucleosomal DNA fragmentation was analysed. Equal amounts of DNA (10 μg) were separated by electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gel and visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. (b–d) At the indicated times after AF and/or SB treatment, the cells were harvested and the cellular proteins were analysed on Western blots probed with antibodies directed against phospho-p38 or p38 (b), caspase-8 (c), caspase-3 or PARP (d). (e) The cytosolic and mitochondrial fractions were prepared from cells treated with 2 μM AF in the absence or presence of 20 μM SB203580. Released cytochrome c was detected in the cytosolic fraction by Western blotting. All experiments in the figure were performed three times, and the data shown represent a typical result obtained from three independent experiments.

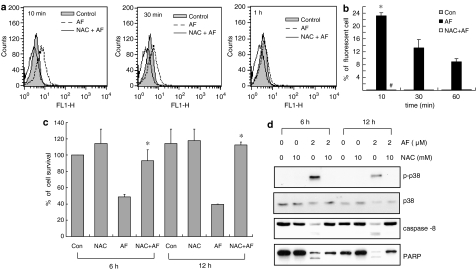

Apoptosis triggered by AF-mediated ROS production

To investigate whether the ROS produced by AF treatment trigger apoptosis via the activation of p38 MAPK, the phosphorylation of p38 MAPK and cell death were examined when ROS production was blocked. As shown in Figure 7a, the population of cells with DCF fluorescence was elevated in the AF-treated group compared with that in the untreated control group. A significant increase in ROS was observed after 10 min of AF treatment, and the level of ROS decreased over time. Pretreatment with the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) effectively inhibited intracellular ROS production and protected the cells from death (Figure 7a–c). NAC also blocked p38 MAPK phosphorylation, procaspase-8 cleavage, and PARP cleavage (Figure 7d). These results indicate that AF generates intracellular ROS, which are a trigger for the apoptotic signal cascade via p38 MAPK activation.

Figure 7.

ROS production in AF-treated HL-60 cells. (a) HL-60 cells were incubated for 10, 30, or 60 min with AF in the absence or presence of 10 mM NAC, after which DCFH-DA was added. After an additional 30-min incubation, the fluorescence intensity of 104 cells was measured by flow-cytometric analysis. The experiment was repeated twice independently and the results were similar. (b) The fluorescent cells in experiment (a) were quantified. Symbols indicate statistical significances (*P<0.05 vs untreated control group. #P<0.05 vs AF-treated group). (c) The cells were treated with AF alone or together with 10 mM NAC. After treatment for 6 or 12 h, the cell numbers were counted with a haemocytometer. Cell viability was estimated by Trypan blue exclusion and the results were expressed as percent of cell survival relative to that after the control treatment. The error bars indicate ±s.d. of triplicate experiments. *P<0.005 relative to a group treated with AF alone. (d) Equal amounts of cell lysates (30 μg) were subjected to electrophoresis and analysed by Western blotting to measure p38 phosphorylation, caspase-8 activation, and PARP cleavage. The same blot was stripped and reprobed with anti-p38 antibody. The data shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Discussion

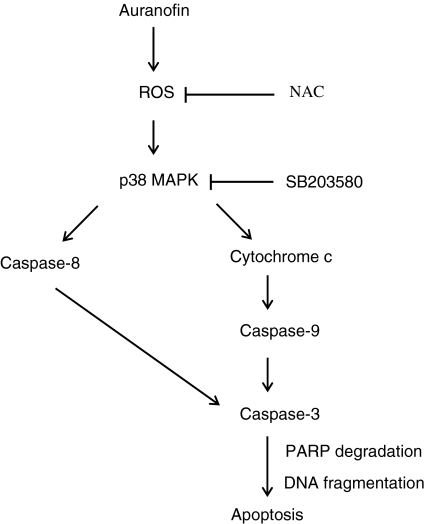

In the present study, the molecular mechanisms underlying the AF-induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells were investigated. The results of this study can be summarized in a schematic representation (Figure 8). In this model, the AF-mediated generation of ROS represents an initiating event in the activation of the apoptotic cascade in HL-60 cells. Increased ROS subsequently activate p38 MAPK and this p38 MAPK activation transduces a signal to initiator caspases to stimulate further apoptotic events. As a result, caspase-3 activation, PARP degradation, and DNA fragmentation follow, and the cells ultimately die.

Figure 8.

Proposed model of the molecular mechanisms underlying AF-induced apoptosis of HL-60 cells, involving ROS generation, p38 MAPK activation, and caspase cascades.

MAP kinases are essential parts of the signal transduction machinery and play central roles in cell growth, differentiation, and programmed cell death (Cobb & Goldsmith, 1995; Karin, 1995; Ohno & Han, 2000). According to our data, only p38 MAPK, and not JNK or ERK, is associated with the proapoptotic activity of AF (Figure 5). We do not know why AF specifically activates p38, even though ROS activate all MAPKs in general. To understand this specificity, a study demonstrating the effects of AF on upstream kinases (MAPK kinases and MAPK kinase kinases) is required.

p38 phosphorylation occurred prior to caspase activation in terms of time, and pretreatment with SB203580 blocked cytochrome c release, caspase-3 and -8 activation, PARP cleavage, and DNA fragmentation (Figures 5 and 6), suggesting that p38 MAPK acts before the cascade of caspase activation. Moreover, intracellular ROS were detected within 1 h after exposure to AF, earlier than p38 MAPK phosphorylation was detected (Figure 7a). Pretreatment with NAC protected cells against AF-induced death by inhibiting p38 MAPK phosphorylation, caspase-8 activation, and PARP cleavage (Figure 7c and d). These findings imply that the ROS trigger is an upstream signal that initiates the series of apoptotic events induced by AF.

Apoptosis can be initiated via two alternative signal pathways: the extrinsic pathway, which acts through death receptors on cell surfaces, and the intrinsic pathway, which acts through the mitochondria (Cohen, 1997; Reed, 1997). In the extrinsic pathway, caspase-8 acts as the initiator caspase and activates downstream effector caspase-3, -6, and -7. In the intrinsic pathway, cytochrome c released from the mitochondria combines with apoptotic protease-activating factor-1 and procaspase-9 to form an apoptosome. At the apoptosome, caspase-9 is activated to become the initiator caspase and then activates the effector caspases. It seems likely that AF-induced apoptosis is associated with both the extrinsic and intrinsic pathways, because both caspase-8 activation and cytochrome c release are observed (Figure 4). Our results demonstrating the involvement of the intrinsic pathway are consistent with the recently reported finding that AF inhibits mitochondrial TrxR and concurrently stimulates cytochrome c release (Rigobello et al., 2004). In the experiments with NAC and SB203580, we also found that AF-mediated ROS triggered the p38 MAPK signal and was linked to caspase-8 activation (Figures 6 and 7). However, our data do not show any connection between caspase-8 activation and the Fas-associated death domain (FADD) or with a mitochondria-dependent pathway through truncated Bid formation (Igney & Krammer, 2002). We are presently investigating whether Fas or tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor signals are involved in AF-induced apoptosis.

The findings of this study and recent reports suggest that AF, which has been widely used in the therapeutic treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, can potentially be developed as an anticancer drug.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Korea Research Foundation Grant funded by the Korean Government (MOEHRD) (R04-2002-000-20121-0). We thank Yuhan Medica Corporation (Gunpo, Korea) for the generous gift of auranofin.

Abbreviations

- AF

auranofin

- APL

acute promyelocytic leukaemia

- ATF-2

activating transcription factor-2

- DCFH-DA

2′,7′-dichlorohydrofluorescein diacetate

- DTT

dithiothreitol

- EDTA

ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- EGTA

ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid

- ERK

extracellular signal-regulated kinase

- FADD

Fas-associated death domain

- IκB

NF-κB inhibitor

- JNK/SAPK

c-Jun N-terminal protein kinase/stress-activated protein kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NAC

N-acetyl-L-cysteine

- NF-κB

NF nuclear factor kappa B

- PARP

poly-ADP-ribose polymerase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PML–RARα

promyelocytic leukaemia–retinoic acid receptor alpha

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulphate

- TRAIL

tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand

- TrxR

thioredoxin reductase

References

- ANTLSPERGER D.S., DIRSCH V.M., FERREIRA D., SU J.L., KUO M.L., VOLLMAR A.M. Ajoene-induced cell death in human promyeloleukemic cells does not require JNK but is amplified by the inhibition of ERK. Oncogene. 2003;22:582–589. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BORG G., ALLANDER E., LUND B., BERG E., BRODIN U., PETTERSSON H., TRANG L. Auranofin improves outcome in early rheumatoid arthritis. Results from a 2-year, double blind placebo controlled study. J. Rheumatol. 1988;15:1747–1754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COBB M.H. MAP kinase pathways. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 1999;71:479–500. doi: 10.1016/s0079-6107(98)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COBB M.H., GOLDSMITH E.J. How MAP kinases are regulated. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:14843–14846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.14843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHEN G.M. Caspases, the executioners of apoptosis. Biochem. J. 1997;326:1–16. doi: 10.1042/bj3260001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAVISON K., MANN K.K., WAXMAN S., MILLER W.H., JR JNK activation is a mediator of arsenic trioxide-induced apoptosis in acute promyelocytic leukemia cells. Blood. 2004;103:3496–3502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GREEN D.R. Apoptotic pathways: the roads to ruin. Cell. 1998;94:695–698. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81728-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GRIGNANI F., FAGIOLI M., ALCALAY M., LONGO L., PANDOLFI P.P., DONTI E., BIONDI A., LO COCO F., GRIGNANI F., PELICCI P.G. Acute promyelocytic leukemia: from genetics to treatment. Blood. 1994;83:10–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GROMER S., ARSCOTT L.D., WILLIAMS C.H., JR, SCHIRMER R.H., BECKER K. Human placenta thioredoxin reductase. Isolation of the selenoenzyme, steady state kinetics, and inhibition by therapeutic gold compounds. J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:20096–20101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.32.20096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HASHIMOTO K., WHITEHURST C.E., MATSUBARA T., HIROHATA K., LIPSKY P.E. Immunomodulatory effects of therapeutic gold compounds. J. Clin. Invest. 1992;89:1839–1848. doi: 10.1172/JCI115788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUANG C., MA W.Y., LI J., DONG Z. Arsenic induces apoptosis through a c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase-dependent, p53-independent pathway. Cancer Res. 1999;59:3053–3058. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IGNEY F.H., KRAMMER P.H. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2002;2:277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEON K.I., JEONG J.Y., JUE D.M. Thiol-reactive metal compounds inhibit NF-κB activation by blocking IκB kinase. J. Immunol. 2000;164:5981–5989. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.11.5981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JEON K.I., BYUN M.S., JUE D.M. Gold compound auranofin inhibits IkappaB kinase (IKK) by modifying Cys-179 of IKKbeta subunit. Exp. Mol. Med. 2003;35:61–66. doi: 10.1038/emm.2003.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KARIN M. The regulation of AP-1 activity by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:16483–16486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.28.16483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM I.S., JIN J.Y., LEE I.H., PARK S.J. Auranofin induces apoptosis and when combined with retinoid acid enhances differentiation of acute promyelocytic leukaemia cells in vitro. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;142:749–755. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KONDOH M., TASAKI E., ARARAGI S., TAKIGUCHI M., HIGASHIMOTO M., WATANABE Y., SATO M. Requirement of caspase and p38MAPK activation in zinc-induced apoptosis in human leukemia HL-60 cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:6204–6211. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03339.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKEAGE M.J. Gold opens mitochondrial pathways to apoptosis. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:1081–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MISTRY A.R., PEDERSEN E.W., SOLOMON E., GRIMWADE D. The molecular pathogenesis of acute promyelocytic leukaemia: implications for the clinical management of the disease. Blood Rev. 2003;17:71–97. doi: 10.1016/s0268-960x(02)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUSTACICH D., POWIS G. Thioredoxin reductase. Biochem. J. 2000;346:1–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHNO K., HAN J. The p38 signal transduction pathway activation and function. Cell Signal. 2000;12:1–13. doi: 10.1016/s0898-6568(99)00071-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REED J.C. Cytochrome c: can't live with it – can't live without it. Cell. 1997;91:559–562. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80442-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIGOBELLO M.P., SCUTARI G., BOSCOLO R., BINDOLI A. Induction of mitochondrial permeability transition by auranofin, a gold (I)-phosphine derivative. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:1162–1168. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RIGOBELLO M.P., SCUTARI G., FOLDA A., BINDOLI A. Mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase inhibition by gold (I) compounds and concurrent stimulation of permeability transition and release of cytochrome c. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;67:689–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SNYDER R.M., MIRABELLI C.K., CROOKE S.J. The cellular pharmacology of auranofin. Semin. Arthritis Rheum. 1987;17:71–80. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(87)90017-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITMAN S.P., CIVOLI F., DANIEL L.W. Protein kinase CβII activation by 1-β-D-arabinosylcytosine is antagonistic to stimulation of apoptosis and Bcl-2α down-regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:23481–23484. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMADA R., SANO H., HLA T., HASHIRAMOTO A., FUKUI W., MIYAZAKI S., KOHNO M., TSUBOUCHI Y., KUSAKA Y., KONDO M. Auranofin inhibits interleukin-1beta-induced transcript of cyclooxygenase-2 on cultured human synoviocytes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;385:71–79. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00707-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]