Abstract

In addition to endothelium-derived relaxing factor and hyperpolarizing factor, vascular endothelium also modulates smooth muscle tone by releasing endothelium-derived contracting factor(s) (EDCF), but the identity of EDCF remains obscure. We studied here the involvement of hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) in endothelium-dependent contraction (EDC) of rat renal artery to acetylcholine (ACh).

ACh (10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M) induced a transient contraction of rat renal artery with intact endothelium in a concentration-related manner, but not in the artery with endothelium removed. In phenylephrine-precontracted renal arteries, ACh induced an endothelium-dependent relaxation response at lower concentrations (10−8–10−6 M), and a relaxation followed by a contraction at higher concentrations (10−5 M). Inhibition of nitric oxide synthase by Nω-nitro-L-arginine (10−4 M) enhanced the EDC to ACh.

Catalase (1000 U ml−1) reduced the EDC to ACh. H2O2 (10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M) induced a similar transient contraction of the renal arteries as ACh, but in an endothelium-independent manner. Inhibition of NAD(P)H oxidase and cyclooxygenase by diphenylliodonium chloride and diclofenac greatly attenuated ACh-induced EDC, while inhibition of xanthine oxidase (allopurinol) and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase (17-octadecynoic acid) did not affect the contraction. Antagonist of thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin H2 receptors (SQ 29548) and thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor (furegrelate) attenuated the contraction to ACh and to H2O2.

In isolated endothelial cells, ACh (10−5 M) induced a transient H2O2 production detected with a fluorescence dye sensitive to H2O2 (2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate). The peak concentration of H2O2 was 5.1 × 10−4 M at 3 min and was prevented by catalase.

Taken together, these results show that ACh triggers H2O2 production through NAD(P)H oxidase activation in the endothelial cells, and that ACh and H2O2 share the same signaling pathway in causing smooth muscle contraction. Therefore, H2O2 is most likely the EDCF in rat renal artery in response to ACh stimulation.

Keywords: Acetylcholine, endothelium-dependent contraction, endothelium-derived contracting factor (EDCF), hydrogen peroxide, renal artery

Introduction

The endothelium plays a crucial role in modulating vascular tone by releasing a number of vasoactive factors. In addition to the endothelium-derived relaxing factor (EDRF) and hyperpolarizing factor (EDHF), endothelial cells also produce contracting factor(s) (EDCF) (Furchgott & Vanhoutte, 1989). The evidence in support of the presence of EDCF was based on (1) endothelium-dependent contraction to various stimulating agents such as acetylcholine (ACh), ATP, caffeine, and calcium ionophore A23187 (Yang et al., 2004); (2) a reversal of this endothelium-dependent relaxation response when higher concentrations of ACh were used (Sunano et al., 1999); and (3) an enhancement of endothelium-dependent relaxation response by blockade of cyclooxygenase (Fortes et al., 1990). Endothelium-dependent contraction has been observed in systematic, cerebral, and pulmonary arteries from several species, including humans (Altiere et al., 1986; Auch-Schwelk et al., 1990; Shirahase et al., 1990; Usui et al., 1993; Nishimura et al., 1995; Saifeddine et al., 1998; Sunano et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1999), suggesting its general presence in the vasculature.

In experiments with isolated systemic vessels, ACh is commonly used as an inducing agent for EDCF release, as shown in conduit arteries (e.g. aorta) (Yang et al., 2002), muscular arteries (e.g. carotid artery) (Zhou et al., 1999), and microvessels (e.g. mesenteric arterioles) (Fortes et al., 1990). However, in most of these studies, ACh-induced endothelium-dependent contraction was either small or absent if a nitric oxide (NO) synthase inhibitor such as Nω-nitro-L-arginine (LNNA) was not used to inhibit NO production, suggesting that upon ACh stimulation NO release was dominant in most systemic arteries, which overwhelms the influence of EDCF. Rat renal artery, however, is different from many other arteries in its response to ACh, because a prominent endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh was shown without NO synthase inhibition, indicating a prevailing EDCF production (Nishimura et al., 1995). Therefore, EDCF may play a greater role in renal than in other arterial beds.

Although the identity of EDCF has not been characterized yet, reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide have been suggested as potential candidates of EDCF in some arteries such as rat aorta (Yang et al., 2002) and canine basilar artery (Katusic & Vanhoutte, 1989), but not in other blood vessels (Auch-Schwelk et al., 1989; Nishimura et al., 1995). The present study was designed to examine whether hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) is involved in the endothelium-dependent contraction response to ACh in the renal artery of rats.

Methods

Animals

Male Wistar–Kyoto rats (WKY), 6–8 months old, were obtained from the rat colony maintained at the McMaster University Central Animal Facilities. The care and use of these animals were in accordance with the guidelines of the Canadian Council on Animal Care.

Reactivity experiments

The procedure for preparing arterial rings and the components of Krebs solution have been described in our previous report (Gao & Lee, 2001). Briefly, the rats were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (50 mg kg−1 i.p.), and then exsanguinated by bleeding from the abdominal aorta. The left and right renal arteries were isolated by dissection and placed in oxygenated Krebs solution at 4°C. Segments, 4-mm long, of the renal arteries (lumen diameter 1–2 mm) were equilibrated under a resting tension of 1.5 g for 1 h in a computerized organ bath system for isometric tension recording. After equilibration, the rings were challenged with 80 mM KCl until a stable contraction was achieved. Functional integrity of the endothelium was established by the relaxation response of these arteries to carbamylcholine chloride (CCh) (10−6 M) in rings precontracted with phenylephrine (PHE) (10−6 M). In some segments, the endothelium was removed by rubbing the internal surface of the ring with a fine wooden stick, and successful removal of endothelium was confirmed by the absence of relaxation response to CCh.

Experimental protocol

To assess the contractile response to ACh, arterial rings with and without endothelium were exposed to different concentrations of ACh. Since the contractile response to each concentration was transient, the concentration–response curves were established by noncumulative addition of ACh in the artery at an interval of 20–30 min. In experiments to assess the effects of catalase, 4-h incubation was used and the incubating medium was changed every hour. A parallel control was used to monitor the time-dependent alteration of contraction to ACh. In some experiments, inactivated catalase by boiling for 10 min was used. To assess the effects of various enzyme inhibitors and receptor antagonists, a 30-min incubation was used prior to adding ACh. Contractile response to KCl (80 mM) was tested 20–25 min after the contraction to ACh had returned to baseline.

In another set of experiments, contractile response to H2O2 was tested in endothelium-intact and -denuded renal arteries. In most cases, one ring was exposed to only one concentration of H2O2, unless the previous concentration of H2O2 did not provoke any response, due to the tachyphylaxis to H2O2 we had noticed previously (Gao & Lee, 2001). Enzyme inhibitors and receptor antagonists were similarly tested as described in ACh-induced contraction.

The contraction to ACh and H2O2 was normalized with the value obtained with contraction to 80 mM KCl. All the inhibitors and receptor antagonists at the concentrations used did not affect the basal tension or the contractions to 80 mM KCl.

Measurement of thromboxane B2 (TXB2)

Samples of the bathing solution in the organ bath were taken before and 5 min after adding ACh, and stored at −80°C until analyzed. This time block was selected because contraction to ACh was transient and the contraction was over within 5 min. The concentration of TXB2 was measured using a TXB2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit. The content of TXB2 was expressed as pg mg−1 wet weight of the arterial rings.

Measurement of H2O2 production in isolated endothelial cells

Under sterile condition, endothelial cells were scraped from the renal arteries into cell culture media (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM)). Endothelial cells were selected with Bandeiraea simplicifolia-1 lectin-conjugated magnetic beads (Silva-Azevedo et al., 2002) from the cell suspension in HEPES buffer (composition in mM: NaCl, 134; KCl, 5.4; MgSO4, 0.8; CaCl2, 1.8; HEPES, 20; glucose 10). Isolated endothelial cells were loaded with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (5 × 10−6 M), a peroxide-sensitive fluorescence dye, for 10 min, then challenged with ACh (10−5 M) (Ohba et al., 1994; Matoba et al., 2000). Fluorescence images were obtained before and 3 min after the application of ACh, using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus 1X81, Japan) and analyzed with the software of Image-Pro Plus (Silver Spring, MD, U.S.A.). Some cells were incubated with catalase (1000 U ml−1) for 1 h before exposure to ACh. The fluorescence intensity with known concentrations of H2O2 (5 × 10−6–5 × 10−3 M) was used as standard to estimate the concentration of ACh-stimulated production of H2O2 in the endothelial cells.

Chemicals

The following chemicals were used: ACh, allopurinol, bandeiraea simplicifolia-1 lectin, CCh, catalase, catalase-polyethelene glycol, 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate, diphenylliodonium chloride, furegrelate sodium, LNNA (Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.); diclofenac sodium, SQ 29548 (RBI, Sigma, St Louis, Missouri, U.S.A.); H2O2 (BDH Inc., Toronto, Canada). DMEM (Gibco BRL, Burlington, Ontario, Canada), magnetic beads (Dynal, Hamburg, Germany); 17-octadecynoic acid (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, Michigan, U.S.A.); TXB2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (Neogen, Lexington, Kentucky, U.S.A.); allopurinol, diphenylliodonium chloride and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate were dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide, and 17-octadecynoic acid and SQ 29548 in absolute ethanol, and diluted in 50% ethanol; all other agents were dissolved in deionized water and prepared fresh daily.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as mean±s.e.m., where n represents the number of rats. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA or unpaired Student's t-test. The differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

Endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh and the effects of NO synthase inhibition on the contraction

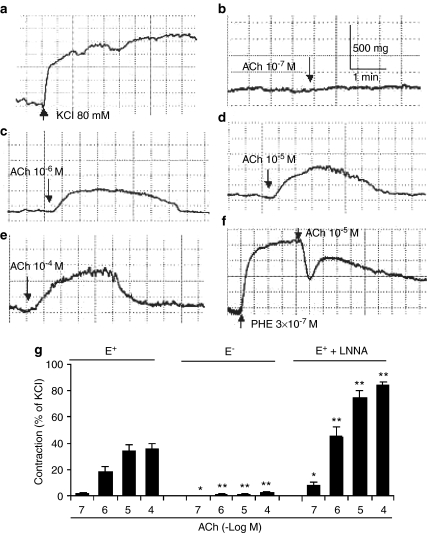

ACh (10−7, 10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M) induced a transient contraction of the endothelium-intact renal artery (Figure 1b–e). The amplitude of the contraction was related to the concentration of ACh applied. In PHE (3 × 10−7 M)-contracted renal arteries with intact endothelium, ACh (10−5 M) produced a biphasic response: a relaxation, followed by a transient contraction at higher concentrations (10−5 M; Figure 1f). Removal of endothelium nearly abolished and NO synthase inhibitor LNNA (10−4 M) enhanced the contraction to ACh (Figure 1g). ACh (10−7–10−5 M) did not induce any contraction in the aorta and mesenteric arteries with intact endothelium, but a small contraction was observed at 10−4 M (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Typical tracings showing endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh at different concentrations at resting tension and in precontracted condition in the renal arteries from WKY. (a) Response to KCl (80 mM). (b–e) Endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh at resting tension. (f) Biphasic response (a relaxation response followed by a contraction response) in PHE (3 × 10−7 M)-precontracted renal arteries to ACh (10−5 M). (g) Summary of ACh-induced contraction in endothelium-intact (E+) arteries (with or without LNNA (10−4 M) and in endothelium-denuded (E−) arteries at resting tension (n=6–7 rats).

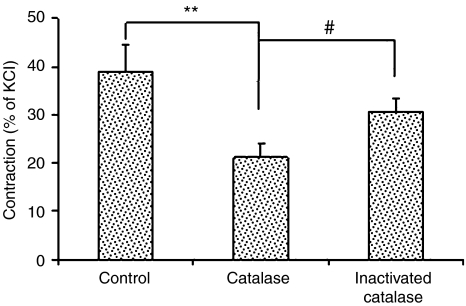

Catalase on ACh-induced contraction

After incubation with catalase (1000 U ml−1) for 4 h, the artery was challenged with ACh (10−5 M). Compared with control, ACh-induced contraction was attenuated by 45% (Figure 2), while the contractile response to KCl (80 mM) was not affected (in grams: control: 0.64±0.07; catalase: 0.59±0.05; P=0.52, n=7 for each). Catalase inactivated by boiling did not inhibit the contraction to ACh.

Figure 2.

Effects of catalase (1000 U ml−1, 4 h incubation) on ACh (10−5 M)-induced endothelium-dependent contraction of renal artery from WKY rats (n=7 rats for control and catalase, n=4 for inactivated catalase). **P<0.01, #P<0.05.

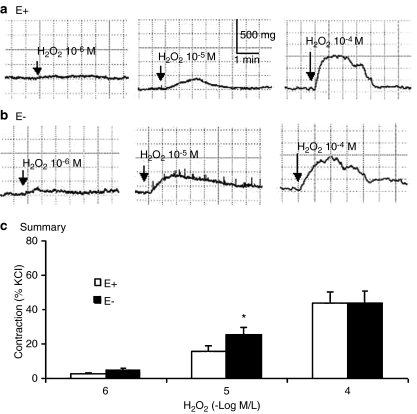

Endothelium-independent contraction to H2O2

H2O2 (10−6, 10−5, and 10−4 M) produced a concentration-associated contraction in endothelium-intact and -denuded renal arteries. Endothelium removal enhanced the contraction to 10−5 M H2O2 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Typical tracings showing endothelium-dependent and -independent contraction to H2O2 at different concentrations in the renal artery of WKY. (a, b) Contractile response of endothelium-intact (E+, a) and -denuded (E−, b) renal arteries. (c) Summary of H2O2-induced contraction in E+ and E− renal arteries (n=7 rats). *P<0.05 compared with E+ renal arteries.

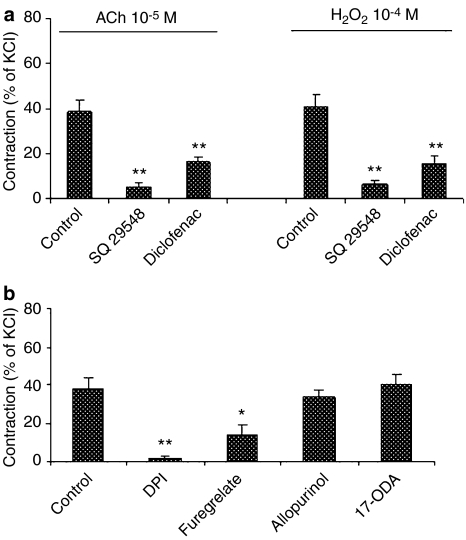

Effects of enzyme inhibitors and thromboxane A2/prostaglandin H2 (TP) receptor antagonist on ACh- and H2O2-induced contraction

Cyclooxygenase inhibitor diclofenac (10−5 M) and TP receptor antagonist SQ 29548 (10−6 M) attenuated both ACh- and H2O2-induced contraction (Figure 4a). NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor diphenylliodonium chloride (10−5 M) and thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor (furegrelate, 10−4 M) reduced the contraction to ACh (Figure 4b). Neither xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol) nor cytochrome P450 monooxygenase inhibitor (17-octadecynoic acid) inhibited the contraction to ACh.

Figure 4.

(a) Effects of thromboxane A2/prostaglandin H2 receptor antagonist (SQ 29548, 10−6 M) and cyclooxygenase inhibitor (diclofenac, 10−5 M) on ACh (10−5 M)- and H2O2 (10−4 M)-induced contraction in the endothelium-intact renal artery of WKY (n=7 rats for each group). (b) Effects of NAD(P)H oxidase inhibitor (diphenylliodonium chloride (DPI), 10−5 M), thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor (furegrelate, 10−4 M), xanthine oxidase inhibitor (allopurinol, 10−4 M), and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase inhibitor (17-octadecynoic acid (17-ODA), 3 × 10−6 M) on ACh (10−5 M)-induced contraction of endothelium-intact renal artery (n=4–6 rats). *P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to the respective control arteries.

TXB2 production stimulated by ACh

The production of TXB2, a stable metabolite of thromboxane A2, was stimulated by ACh (10−5 M) (in pg mg−1 wet weight; before ACh: 39.7±7.5; after ACh: 78.3±13.8; P<0.01, n=10).

ACh-induced H2O2 production in isolated endothelial cells

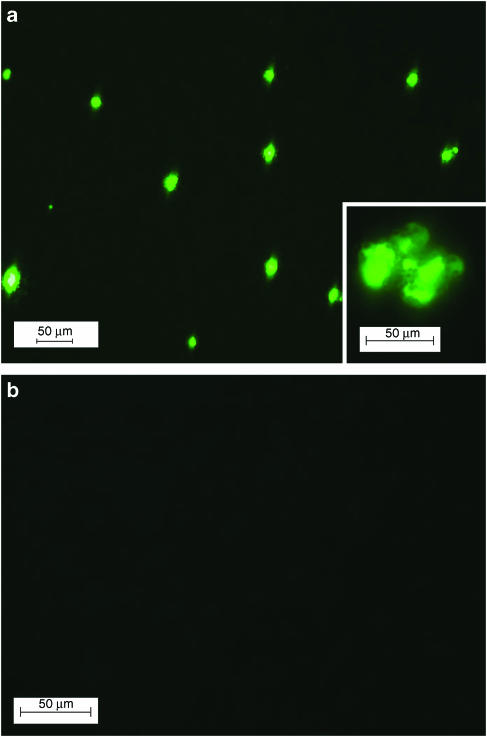

In endothelial cells isolated from renal arteries and loaded with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (5 × 10−6 M for 10 min), ACh (10−5 M) stimulated a quick increase in fluorescence density, which was prevented by catalase-polyethelene glycol (500 U ml−1, incubated for 1 h at room temperature), indicating the production of H2O2 (Figure 5). The concentration of H2O2 generated in the endothelial cells upon ACh stimulation, estimated with a standard curve established with H2O2 (5 × 10−6–5 × 10−3 M; r2=0.94), was 5.13 × 10−4 M. The increase in fluorescence intensity was transient, peaking at 2–3 min and gradually disappearing within 5–10 min. No fluorescence was observed in 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate-loaded cells before ACh challenge.

Figure 5.

ACh (10−5 M)-induced production of H2O2 by endothelial cells from WKY renal arteries detected with 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (5 μM). (a) Image obtained 3 min after application of ACh, showing H2O2 production as indicated by fluorescent cells. The inset shows a higher magnification of fluorescent endothelial cells attached to beads. (b) Image of cells pretreated with catalase-polyethelene glycol (500 U ml−1, 1 h incubation), showing the absence of fluorescent cells (magnification bar represents 50 μm).

Discussion

The novel finding from this study is that H2O2 is most likely the EDCF in rat renal arteries in their response to ACh stimulation. Involvement of ROS in endothelium-dependent contraction had been studied, but the results were conflicting. Superoxide and H2O2 were suggested as EDCF in canine basilar artery (Katusic & Vanhoutte, 1989) and in rat aorta (Yang et al., 2002), but other studies did not support this conclusion (Auch-Schwelk et al., 1989; Nishimura et al., 1995). In this study, we propose that H2O2 is an EDCF of the renal arteries in response to ACh based on the following findings. Firstly, catalase, an enzyme decomposing H2O2, reduced ACh-induced endothelium-dependent contraction, indicating the involvement of H2O2. Secondly, H2O2 directly contracted the renal arteries in an endothelium-independent manner, and the appearance of H2O2-induced contraction was similar to that by ACh (transient in nature and similar in shape), suggesting that H2O2 could act as a mediator of ACh-induced endothelium-dependent contraction. Thirdly, ACh stimulated H2O2 production through NADP(H) oxidase in the endothelial cells. The concentration of H2O2 generated was within the range to cause smooth muscle contraction, and the transiency of this increase matched the observed transient contraction. H2O2 generated in endothelial cells can diffuse to the underlying smooth muscles easily because H2O2 is a membrane-permeable molecule. Fourthly, both ACh- and H2O2-induced contractile responses were sensitive to inhibitors of cyclooxygenase and to the antagonist of thromboxane A2 and prostaglandin H2 receptors, suggesting that ACh and H2O2 were sharing a common signaling pathway. In short, our results in conjunction with others suggest that ACh triggers H2O2 production in the endothelial cells, which causes smooth muscles contraction. Therefore, H2O2 generated from the endothelial cells in response to ACh is the EDCF in the renal arteries.

Thromboxane A2, or cyclooxygenase metabolites in general, had been suggested as EDCF by several studies, based on the inhibitory effects of respective thromboxane A2/prostaglandin H2 receptor antagonists and/or cyclooxygenase inhibitors on endothelium-dependent contraction (Altiere et al., 1986; Auch-Schwelk et al., 1990; Fujiwara et al., 1992; Taddei & Vanhoutte, 1993; Nishimura et al., 1995). However, this conclusion may not necessarily be true because both the inhibition of EDCF release and the interruption of EDCF signaling pathway could potentially attenuate the endothelium-dependent contraction. Previous studies on rat mesenteric arteries and on aorta have shown that H2O2 causes vasoconstriction through thromboxane A2 or cyclooxygenase metabolites in smooth muscles (Rodriguez-Martinez et al., 1998; Gao & Lee, 2001). In this study, we found that cyclooxygenase inhibitor diclofenac and thromboxane A2 receptor antagonist SQ 29548 similarly inhibited ACh-induced endothelium-dependent contraction and H2O2-induced endothelium-independent contraction in rat renal arteries. We also found that ACh stimulated a two-fold increase of TXB2 production, and that thromboxane A2 synthase inhibitor furegrelate attenuated ACh-induced contraction in rat renal arteries, similar to our previous finding in H2O2-induced contraction of rat mesenteric arteries (Gao & Lee, 2001). In a separate experiment, we found that a two-fold increase of thromboxane A2 mimics U 46619 (from 1 to 2 nM) induced a 8.5-fold increase in the contraction (8.3–70.6% of KCl contraction). These results suggest that both ACh and H2O2 contracted the vessel through a cyclooxygenase–thromboxane A2 pathway. Furthermore, our finding using isolated endothelial cells that ACh stimulates H2O2 production in the endothelial cells of the renal arteries, and that the H2O2 produced was within the range to initiate contraction of the vessels, strongly suggests that endothelial cell-derived H2O2, rather than thromboxane A2 or other cyclooxygenase metabolites, matches the criteria for an EDCF in this artery.

Catalase has been a key enzyme used to test the involvement of H2O2 in endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh in in vitro studies with isolated vessels, but the results were not consistent (Auch-Schwelk et al., 1989; Nishimura et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2002). The reasons behind this discrepancy are not clear, but may be related to the length of incubation time. The uptake of exogenously applied catalase by endothelial cells is a slow process (Tokuda et al., 1993). The usual incubation time with catalase used in most studies was around 30 min or less (Auch-Schwelk et al., 1989; Nishimura et al., 1995; Yang et al., 2002), so that the amount of catalase entering endothelial cells in the arterial tissue may not be enough to scavenge a sudden surge of ACh-triggered H2O2 effectively. In cultured endothelial cells, a 2-h incubation was used to inhibit angiotensin II-induced H2O2 generation (Touyz & Schiffrin, 1999). In our preliminary experiments with isolated renal arteries, we found that a 2-h incubation with catalase only showed a slight inhibition, while a 4-h incubation with catalase attenuated ACh-induced endothelium-dependent contraction by 45%. This attenuation did not seem to be a nonspecific inhibition of contraction because contraction responses to KCl were not affected, and boiled catalase did not inhibit the contraction to ACh.

H2O2 is primarily formed by dismutation of superoxide. It is well known that endothelial cells produce superoxide by several enzymes, including NAD(P)H oxidase, xanthine oxidase, cytochrome P450 monooxygenase, and uncoupled NO synthase (Rosen & Freeman, 1984; Mohazzab et al., 1994; Ago et al., 2004; Cai, 2005; Munzel et al., 2005). Expression of NAD(P)H oxidase has been shown in endothelial cells (Ago et al., 2005). In this study, inhibitor of NAD(P)H oxidase greatly reduced the endothelium-dependent contraction to ACh, suggesting that this enzyme was possibly the main source of H2O2. Cyclooxygenase inhibitor also attenuated ACh-induced contraction. This could be due to its involvement in H2O2 generation, and/or its involvement in signaling pathway of H2O2-induced contraction, as shown in other vascular tissues (Gao & Lee, 2001; Ghosh et al., 2004). Uncoupled NO synthase, xanthine oxidase, and cytochrome P450 monooxygenase did not seem to be involved, since inhibition of these enzymes by LNNA, allopurinol, and 17-octadecynoic acid did not attenuate the contraction to ACh.

H2O2 has multiple vasomotor actions. It is a vasocontrictor in many vessels (Yang et al., 1998b; Sunano et al., 1999; Zhou et al., 1999; 2001), and a vasodilator in some arteries (Hayabuchi et al., 1998; Yang et al., 1998a; Fujimoto et al., 2001). Even in the same artery, lower concentration causes contraction, while higher concentration produces a relaxation response (Gao et al., 2003). Therefore, H2O2 modulates vessel function in a complex way. Recent studies also showed that H2O2 is involved in angiotensin II- or serotonin-induced contraction (Frank et al., 2000; Srivastava et al., 2002). In mouse mesenteric artery, H2O2 has been suggested to be an EDHF (Matoba et al., 2000), and in rat mesenteric artery we have demonstrated that H2O2 induced relaxation through the activation of K+ channels (Gao et al., 2003). Results from this study showed that H2O2 can be a mediator for endothelium-dependent contraction in some arteries such as rat renal artery, and therefore adding new insights to our understanding on the control of vascular functions by H2O2.

ACh has the potential to induce the production of EDRF such as NO (Furchgott & Vanhoutte, 1989) and EDHF (Jiang et al., 2000; Matoba et al., 2000), and EDCF (Yang et al., 2002). In PHE-precontracted renal arteries, a single concentration of ACh (10−5 M) induced a biphasic response: a relaxation followed by a contraction, suggesting the release of both relaxing and contracting factors, and the mechanical consequence of the stimulation with ACh will depend on the interaction among these counteracting factors. NO seems to be the main relaxing factor because the relaxation component in the response to ACh was almost abolished by NO synthase inhibition, and the potentiation of EDCF-mediated response by LNNA can be explained by inhibition of NO release. In most systemic arteries, the presence of EDCF was demonstrated only when a high concentration of NO synthase inhibitor, such as 100 μM LNNA, was used. However, such a high concentration of NO synthase inhibitor may not be physiological because the plasma level of the endogenous NO synthase inhibitor, asymmetric dimethylarginine, ranges from 500 nM to 1.2 μM (Vallance & Leiper, 2004). In our study, ACh stimulation of rat renal artery clearly showed an effect of EDCF without NO synthase inhibition. This suggests that the production of EDCF dominates over EDRF and/or EDHF in the renal artery in response to higher concentration of ACh. In hypertension, the production of EDCF of renal vessels is enhanced (Zhou et al., 2001; Vanhoutte et al., 2005), suggesting a pathological role of EDCF in certain diseases.

In conclusion, we found that in rat renal artery endogenous H2O2 is most likely the EDCF in response to ACh stimulation. Since kidney is a rich source of ROS (Baud & Ardaillou, 1986), and ROS may play a role in renal microcirculation (Schnackenberg, 2002), the role of this EDCF in the control of renal functions deserves further investigations.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Liying Su, Miss Hara Kim and Ashley Chao, and Mr Nathan Ni for their technical assistance; Ms M. Szewczyk and Dr A.K. Grover for their guidance in the isolation of endothelial cells; Dr W.G. Foster for the use of his fluorescence microscopy. This study was supported by the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Ontario, Canada.

Abbreviations

- ACh

acetylcholine

- CCh

carbamylcholine chloride

- EDCF

endothelium-derived contracting factor

- EDHF

endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor

- EDRF

endothelium-derived relaxing factor

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- LNNA

Nω-nitro-L-arginine

- NO

nitric oxide

- PHE

phenylephrine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TP

thromboxane and prostaglandin

- TXB2

thromboxane B2

- WKY

Wistar–Kyoto rats

References

- AGO T., KITAZONO T., KURODA J., KUMAI Y., KAMOUCHI M., OOBOSHI H., WAKISAKA M., KAWAHARA T., ROKUTAN K., IBAYASHI S., IIDA M. NAD(P)H oxidases in rat basilar arterial endothelial cells. Stroke. 2005;36:1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000163111.05825.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGO T., KITAZONO T., OOBOSHI H., IYAMA T., HAN Y.H., TAKADA J., WAKISAKA M., IBAYASHI S., UTSUMI H., IIDA M. Nox4 as the major catalytic component of an endothelial NAD(P)H oxidase. Circulation. 2004;109:227–233. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000105680.92873.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTIERE R.J., KIRITSY-ROY J.A., CATRAVAS J.D. Acetylcholine-induced contractions in isolated rabbit pulmonary arteries: role of thromboxane A2. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1986;236:535–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUCH-SCHWELK W., KATUSIC Z.S., VANHOUTTE P.M. Contractions to oxygen-derived free radicals are augmented in aorta of the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Hypertension. 1989;13:859–864. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.13.6.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AUCH-SCHWELK W., KATUSIC Z.S., VANHOUTTE P.M. Thromboxane A2 receptor antagonists inhibit endothelium-dependent contractions. Hypertension. 1990;15:699–703. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.15.6.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAUD L., ARDAILLOU R. Reactive oxygen species: production and role in the kidney. Am. J. Physiol. 1986;251:F765–F776. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1986.251.5.F765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CAI H. Hydrogen peroxide regulation of endothelial function: origins, mechanisms, and consequences. Cardiovasc. Res. 2005;68:26–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2005.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FORTES Z.B., NIGRO D., SCIVOLETTO R., DE CARVALHO M.H. Indirect evidence for an endothelium-derived contracting factor released in arterioles of deoxycorticosterone acetate salt hypertensive rats. J. Hypertens. 1990;8:1043–1048. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199011000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FRANK G.D., EGUCHI S., YAMAKAWA T., TANAKA S., INAGAMI T., MOTLEY E.D. Involvement of reactive oxygen species in the activation of tyrosine kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase by angiotensin II. Endocrinology. 2000;141:3120–3126. doi: 10.1210/endo.141.9.7630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJIMOTO S., ASANO T., SAKAI M., SAKURAI K., TAKAGI D., YOSHIMOTO N., ITOH T. Mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide-induced relaxation in rabbit mesenteric small artery. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;412:291–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00940-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FUJIWARA M., USUI H., KURAHASHI K., JINO H., SHIRAHASE H., MEKATA F. Endothelium-dependent contraction produced by acetylcholine and relaxation produced by histamine in monkey basilar arteries. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1992;20 (Suppl 12):S114–S116. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199204002-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FURCHGOTT R.F., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-derived relaxing and contracting factors. FASEB J. 1989;3:2007–2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO Y.J., HIROTA S., ZHANG D.W., JANSSEN L.J., LEE R.M. Mechanisms of hydrogen-peroxide-induced biphasic response in rat mesenteric artery. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:1085–1092. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAO Y.J., LEE R.M. Hydrogen peroxide induces a greater contraction in mesenteric arteries of spontaneously hypertensive rats through thromboxane A(2) production. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1639–1646. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GHOSH M., WANG H.D., MCNEILL J.R. Role of oxidative stress and nitric oxide in regulation of spontaneous tone in aorta of DOCA-salt hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;141:562–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYABUCHI Y., NAKAYA Y., MATSUOKA S., KURODA Y. Hydrogen peroxide-induced vascular relaxation in porcine coronary arteries is mediated by Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Heart Vessels. 1998;13:9–17. doi: 10.1007/BF02750638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JIANG F., LI C.G., RAND M.J. Mechanisms of nitric oxide-independent relaxations induced by carbachol and acetylcholine in rat isolated renal arteries. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:1191–1200. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATUSIC Z.S., VANHOUTTE P.M. Superoxide anion is an endothelium-derived contracting factor. Am. J. Physiol. 1989;257:H33–H37. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1989.257.1.H33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MATOBA T., SHIMOKAWA H., NAKASHIMA M., HIRAKAWA Y., MUKAI Y., HIRANO K., KANAIDE H., TAKESHITA A. Hydrogen peroxide is an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 2000;106:1521–1530. doi: 10.1172/JCI10506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MOHAZZAB K.M., KAMINSKI P.M., WOLIN M.S. NADH oxidoreductase is a major source of superoxide anion in bovine coronary artery endothelium. Am. J. Physiol. 1994;266:H2568–H2572. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1994.266.6.H2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MUNZEL T., DAIBER A., ULLRICH V., MULSCH A. Vascular consequences of endothelial nitric oxide synthase uncoupling for the activity and expression of the soluble guanylyl cyclase and the cGMP-dependent protein kinase. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2005;25:1551–1557. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000168896.64927.bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NISHIMURA Y., USUI H., KURAHASHI K., SUZUKI A. Endothelium-dependent contraction induced by acetylcholine in isolated rat renal arteries. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;275:217–221. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00023-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OHBA M., SHIBANUMA M., KUROKI T., NOSE K. Production of hydrogen peroxide by transforming growth factor-beta 1 and its involvement in induction of egr-1 in mouse osteoblastic cells. J. Cell Biol. 1994;126:1079–1088. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RODRIGUEZ-MARTINEZ M.A., GARCIA-COHEN E.C., BAENA A.B., GONZALEZ R., SALAICES M., MARIN J. Contractile responses elicited by hydrogen peroxide in aorta from normotensive and hypertensive rats. Endothelial modulation and mechanism involved. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1329–1335. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROSEN G.M., FREEMAN B.A. Detection of superoxide generated by endothelial cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1984;81:7269–7273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.23.7269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAIFEDDINE M., ROY S.S., AL ANI B., TRIGGLE C.R., HOLLENBERG M.D. Endothelium-dependent contractile actions of proteinase-activated receptor-2-activating peptides in human umbilical vein: release of a contracting factor via a novel receptor. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1998;125:1445–1454. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHNACKENBERG C.G. Physiological and pathophysiological roles of oxygen radicals in the renal microvasculature. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2002;282:R335–R342. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00605.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIRAHASE H., USUI H., SHIMAJI H., KURAHASHI K., FUJIWARA M. Endothelium-dependent contraction induced by platelet-derived substances in canine basilar arteries. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1990;255:182–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SILVA-AZEVEDO L., BAUM O., ZAKRZEWICZ A., PRIES A.R. Vascular endothelial growth factor is expressed in endothelial cells isolated from skeletal muscles of nitric oxide synthase knockout mice during prazosin-induced angiogenesis. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002;297:1270–1276. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02370-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SRIVASTAVA P., RAJANIKANTH M., RAGHAVAN S.A., DIKSHIT M. Role of endogenous reactive oxygen derived species and cyclooxygenase mediators in 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced contractions in rat aorta: relationship to nitric oxide. Pharmacol. Res. 2002;45:375–382. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUNANO S., WATANABE H., TANAKA S., SEKIGUCHI F., SHIMAMURA K. Endothelium-derived relaxing, contracting and hyperpolarizing factors of mesenteric arteries of hypertensive and normotensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;126:709–716. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TADDEI S., VANHOUTTE P.M. Endothelium-dependent contractions to endothelin in the rat aorta are mediated by thromboxane A2. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1993;22 (Suppl 8):S328–S331. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199322008-00086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOKUDA H., MASUDA S., TAKAKURA Y., SEZAKI H., HASHIDA M. Specific uptake of succinylated proteins via a scavenger receptor-mediated mechanism in cultured brain microvessel endothelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993;196:18–24. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.2210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TOUYZ R.M., SCHIFFRIN E.L. Ang II-stimulated superoxide production is mediated via phospholipase D in human vascular smooth muscle cells. Hypertension. 1999;34:976–982. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- USUI H., KURAHASHI K., SHIRAHASE H., JINO H., FUJIWARA M. Endothelium-dependent contraction produced by acetylcholine and relaxation produced by histamine in monkey basilar arteries. Life Sci. 1993;52:377–387. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(93)90151-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VALLANCE P., LEIPER J. Cardiovascular biology of the asymmetric dimethylarginine:dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase pathway. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2004;24:1023–1030. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000128897.54893.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VANHOUTTE P.M., FELETOU M., TADDEI S. Endothelium-dependent contractions in hypertension. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;144:449–458. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG D., FELETOU M., BOULANGER C.M., WU H.F., LEVENS N., ZHANG J.N., VANHOUTTE P.M. Oxygen-derived free radicals mediate endothelium-dependent contractions to acetylcholine in aortas from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2002;136:104–110. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG D., GLUAIS P., ZHANG J.N., VANHOUTTE P.M., FELETOU M. Endothelium-dependent contractions to acetylcholine, ATP and the calcium ionophore A 23187 in aortas from spontaneously hypertensive and normotensive rats. Fundament. Clin. Pharmacol. 2004;18:321–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.2004.00247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Z.W., ZHANG A., ALTURA B.T., ALTURA B.M. Endothelium-dependent relaxation to hydrogen peroxide in canine basilar artery: a potential new cerebral dilator mechanism. Brain Res. Bull. 1998a;47:257–263. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00120-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Z.W., ZHENG T., ZHANG A., ALTURA B.T., ALTURA B.M. Mechanisms of hydrogen peroxide-induced contraction of rat aorta. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1998b;344:169–181. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)01576-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU M.S., KOSAKA H., TIAN R.X., ABE Y., CHEN Q.H., YONEYAMA H., YAMAMOTO A., ZHANG L. L-Arginine improves endothelial function in renal artery of hypertensive Dahl rats. J. Hypertens. 2001;19:421–429. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200103000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU M.S., NISHIDA Y., CHEN Q.H., KOSAKA H. Endothelium-derived contracting factor in carotid artery of hypertensive Dahl rats. Hypertension. 1999;34:39–43. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]