Abstract

Small molecule rescue of mutant forms of human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA II) occurs by participation of exogenous donors/acceptors in the proton transfer pathway between the zinc-bound water and solution. To examine more thoroughly the energetics of this activation, we have constructed a mutant, H64W HCA II, which we have shown is activated by 4-methylimidazole (4-MI) by a mechanism involving the binding of 4-MI to the side chain of Trp-64 ∼8 Å from the zinc. A series of experiments are consistent with the activation of H64W HCA II by the interaction of imidazole and pyridine derivatives as exogenous proton donors with the indole ring of Trp-64; these experiments include pH profiles and H/D solvent isotope effects consistent with proton transfer, observation of approximately fourfold greater activation with the mutant containing Trp-64 compared with Gly-64, and the observation by x-ray crystallography of the binding of 4-MI associated with the indole side chain of Trp-64 in W5A-H64W HCA II. Proton donors bound at the less flexible side chain of Trp-64 in W5A-H64W HCA II do not show activation, but such donors bound at the more flexible Trp-64 of H64W HCA II do show activation, supporting suggestions that conformational mobility of the binding site is associated with more efficient proton transfer. Evaluation using Marcus theory showed that the activation of H64W HCA II by these proton donors was reflected in the work functions wr and wp rather than in the intrinsic Marcus barrier itself, consistent with the role of solvent reorganization in catalysis.

INTRODUCTION

The activation or rescue of catalytic activity of variants of human carbonic anhydrase II (HCA II) by exogenous proton donors/acceptors provides an opportunity to probe the active-site cavity of carbonic anhydrase for locations from which proton transfer can occur. This has value not only for understanding proton transfer in the catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase, but also as a model for proton transfer that may be applied to more complex cases of proton transport in protein systems. The catalysis by α-class carbonic anhydrases in the hydration of CO2 and dehydration of bicarbonate occurs in two stages shown in Eqs. 1 and 2 (1–4). The first stage is the conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate by reaction with a zinc-bound hydroxide; the dissociation of bicarbonate leaves a water molecule at the zinc (Eq. 1).

|

|

(1) |

There is no evidence of rate-contributing proton transfer in the steps of Eq. 1 (5,6). The second stage is the transfer of a proton to solution to regenerate the zinc-bound hydroxide (Eq. 2); here B denotes an exogenous proton acceptor from solution or a residue of the enzyme itself such as His-64 that subsequently transfers the proton to solution (7,8).

|

(2) |

Crystal structures of HCA II have shown that the side chain of His-64 can occupy two conformations, an inward orientation in which the imidazole side chain is ∼7 Å away from the zinc and an outward orientation at ∼12 Å away from the zinc. There appears to be little barrier to interconversion of these rotamers, and it has been suggested that this flexibility contributes to efficient proton transfer (9,10). The distance between the imidazole side chain of His-64 in either conformation and the zinc-bound solvent molecule is too distant for direct proton transfer (2,9,10), and it appears that proton transfer must proceed through intervening water molecules (11).

Binding sites in the active-site cavity HCA II and mutants have been found for small molecules suggested to be activators of catalysis (12–16). Two binding sites for the activator 4-methylimidazole (4-MI) were found, one associated with the side chain of Trp-5 (12) and a second with the side chains of Glu-69 and Asp-72 (16). The issue of whether the sites determined by crystallography were productive binding sites was investigated by altering these binding sites through mutagenesis and determining whether small molecule rescue was changed. It was determined that the binding sites of 4-MI associated with the side chains of Trp-5 (12) and Asp-72 (unpublished) did not contribute to proton transfer in catalysis. A reasonable explanation is that they were too far (>12 Å) from the zinc for productive proton transfer. These studies suggested whether a mutant of HCA II could be engineered with a binding site for small molecule rescue placed closer to the zinc, since, at residue 64 in a mutant containing H64W, the energetic features of the activation could be examined by variation of the rescuing proton donor.

In this report, we describe the structural details of a binding site at Trp-64 in small molecule rescue of a mutant of HCA II, a binding site that is demonstrated to be a productive participant in catalysis by comparing activation of H64W HCA II with that of H64G HCA II. The binding of 4-MI appears in a π-stacking interaction with the indole side chain of Trp-64 as determined from an x-ray crystal structure. The activation of H64W and H64G HCA II by derivatives of imidazole and pyridine are presented in free energy plots, which are interpreted by analogy with nonenzymic, bimolecular proton transfer, and in terms of Marcus rate theory (17–19). The results emphasize the role of solvation in the enhancement of catalysis caused by small molecule rescue. The data identify regions of the active-site cavity from which proton transfer is efficient and contribute to our understanding of catalysis influenced in rate by solvent rearrangement and a facile proton transfer step with low kinetic barrier.

METHODS

Enzymes

Site-specific mutants of HCA II (H64G; H64W; W5A-H64W) were prepared and expressed by transforming into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3)pLysS as previously described (20). The sequences were confirmed from the DNA of the entire coding region for carbonic anhydrase in the expression vector. Carbonic anhydrases were purified using affinity chromatography with p-(aminomethyl)-benzene-sulfonamide coupled to agarose beads (21), followed by extensive dialysis. Matrix-assisted, laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry gave results consistent with the protein sequences. Purity of enzyme samples was determined by electrophoresis on a 10% polyacrylamide gel stained with Coomassie blue. Concentrations of HCA II and mutants were determined from the molar absorptivity at 280 nm (5.5 × 104 M−1 cm−1), and by titration with the tight binding inhibitor ethoxzolamide while observing enzyme-catalyzed 18O exchange between CO2 and water. These measurements gave close agreement.

Crystallography

Crystals of mutants of HCA II were obtained using the hanging drop vapor-diffusion method (22). The crystallization drops were prepared by mixing 5 μL of protein (concentration ∼20.0 mg/mL in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.8) with 5 μL of the precipitant solution (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.2, and 2.3 M ammonium sulfate) at 277 K and allowed to equilibrate against 1000 μL of the precipitant solution. For the co-crystals containing 4-MI and W5A-H64W HCA II, the crystallization buffer was prepared as described above with the addition of 50 mM 4-MI. Useful crystals were observed five days after the crystallization setup. X-ray diffraction data sets were collected using an R-AXIS IV++ image plate system with Osmic mirrors and a Rigaku HU-H3R Cu rotating anode operating at 50 kV and 100 mA (Rigaku, The Woodlands, TX). The crystals were quick-dipped in a cryoprotectant (30% glycerol in precipitant solution) before flash-freezing using an Oxford Cryosystems device (Devens, MA), and all data sets were collected at 100 K. The crystal-to-detector distance was set to 80 mm for H64W and 100 mm for W5A-H64W HCA II with and without 4-MI. The oscillation steps were 1° with a 10-min exposure per image. X-ray data indexing was performed using DENZO and scaled and reduced with SCALEPACK (23). Data collection statistics for each resolution bin are given in Supplementary Material Table S1. All models were built using O, ver. 7 (24). Refinement was carried out with CNS, ver. 1.1 (25). The isomorphous wild-type HCA II crystal structure (Protein Data Bank entry 2CBA (26) was used to phase the data sets. To avoid phase-bias of the model, the zinc ion, mutated side chains, and water molecules were removed. After one cycle of rigid body refinement, annealing by heating to 3000 K with gradual cooling, geometry-restrained position refinement, and temperature factor refinement, the 2Fo-Fc Fourier electron density maps were generated. These electron density maps clearly showed the position of the zinc ion and the mutated residues, which were subsequently built into their respective density. For the W5A-H64W HCA II and 4-MI cocrystal data, Fo-Fc Fourier electron density maps were generated and the 4-MI molecule was placed in the electron density and subsequently included in refinement cycles. After several cycles of temperature factor and energy minimization refinement, solvent molecules were incorporated into the models using the automatic water-picking program in CNS until no more water molecules were found at a 2.0 σ contour level. Refinement of the models continued until convergence of Rcryst and Rfree was reached. Refinement and model statistics are given in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Crystallographic refinement and final model statistics for H64W, W5A-H64W HCA II, and W5A-H64W HCA II in complex with 4-MI

| H64W | W5A-H64W | W5A-H64W + 4-MI | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution (Å) | 20.0–1.80 | 20.0–1.80 | 20.0–1.80 |

| Rcryst* | 0.204 | 0.208 | 0.202 |

| Rfree† | 0.242 | 0.241 | 0.238 |

| No. of residues | 258 | 258 | 258 |

| No. of protein atoms | 2062 | 2053 | 2053 |

| No. H2O molecules | 191 | 160 | 190 |

| No. 4-MI atoms | n.a. | n.a. | 8 |

| RMSD for bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.005 |

| RMSD for angles (°) | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

| Average B-factors (Å2) | |||

| Main/side chains | 13.5/16.2 | 15.9/18.3 | 12.8/15.2 |

| Solvent | 23.5 | 23.8 | 22.7 |

| 4-MI/Trp64 | n.a/30.2 | n.a/16.3 | 33.8/13.9 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)‡ | |||

| Most favored | 88.9 | 89.4 | 88.9 |

| Additionally allowed | 11.1 | 10.6 | 11.1 |

Rcryst = Σ‖Fo| − |Fc‖/Σ |Fo|.

Rfree is calculated the same as Rcryst for data omitted from refinement (5% of reflections for all data sets).

No amino acids were in generously allowed or disallowed regions of the Ramachandran plot, as defined by Procheck (40).

Oxygen-18 exchange

The 18O-exchange method was used to measure the enhancement of carbonic anhydrase catalysis caused by addition of exogenous proton donors. The activators used in this study and their pKa values under the conditions of these experiments are given in the legend to Fig. 4. The 18O-exchange method is based on the measurement by membrane-inlet mass spectrometry of the rate of change in the distribution of 18O between  and water at chemical equilibrium (27,28) (Eqs. 3 and 4). The 18O-exchange method has the advantage that it is carried out at chemical equilibrium and pH control is not a problem; very low as well as very large concentrations of proton donors/acceptors can be used (27).

and water at chemical equilibrium (27,28) (Eqs. 3 and 4). The 18O-exchange method has the advantage that it is carried out at chemical equilibrium and pH control is not a problem; very low as well as very large concentrations of proton donors/acceptors can be used (27).

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

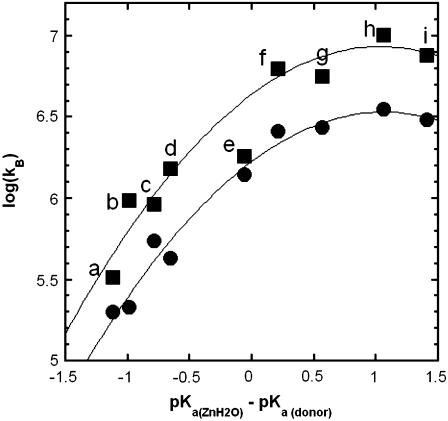

FIGURE 4.

Values of the rate constant  for catalysis by (▪) H64W HCA II; and (•) H64G HCA II as enhanced by the following exogenous proton donors. Values in parentheses are the solution pKa obtained by titration at 0.2 M ionic strength: (a) 1,2-dimethylimidazole (pKa 8.3), (b) 2-methylimidazole (8.2), (c) 2-ethylimidazole (8.0), (d) 4-methylimidazole (7.9), (e) 1-methylimidazole (7.3), (f) imidazole (7.0), (g) 3,4-dimethylpyridine (6.7), (h) 4-methylpyridine (6.1), and (i) 3-methylpyridine (5.8). These measurements were made a 25°C. The value of the pKa of the zinc-bound water in H64W HCA II is 7.3 and for H64G, 7.2 under these conditions determined from its pH profile in kcat/Km for hydration of CO2. Each measurement was made at a pH equivalent to the pKa of the donor. Ionic strength in each measurement was maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of sodium sulfate. Solid lines in both plots are fits to the Marcus equation (9) with parameters given in Table 2.

for catalysis by (▪) H64W HCA II; and (•) H64G HCA II as enhanced by the following exogenous proton donors. Values in parentheses are the solution pKa obtained by titration at 0.2 M ionic strength: (a) 1,2-dimethylimidazole (pKa 8.3), (b) 2-methylimidazole (8.2), (c) 2-ethylimidazole (8.0), (d) 4-methylimidazole (7.9), (e) 1-methylimidazole (7.3), (f) imidazole (7.0), (g) 3,4-dimethylpyridine (6.7), (h) 4-methylpyridine (6.1), and (i) 3-methylpyridine (5.8). These measurements were made a 25°C. The value of the pKa of the zinc-bound water in H64W HCA II is 7.3 and for H64G, 7.2 under these conditions determined from its pH profile in kcat/Km for hydration of CO2. Each measurement was made at a pH equivalent to the pKa of the donor. Ionic strength in each measurement was maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of sodium sulfate. Solid lines in both plots are fits to the Marcus equation (9) with parameters given in Table 2.

The measured variables are the atom fraction of 18O in 12C- and 13C-containing species of CO2 as a function of time. An Extrel EXM-200 mass spectrometer with a membrane-inlet probe (27) was used to measure the isotopic content of CO2. Solutions contained 25 mM total concentration of all species of CO2 unless otherwise indicated. All experiments were performed at 25°C and in all experiments ionic strength was held at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of sodium sulfate.

This approach yields two rates for the 18O exchange catalyzed by carbonic anhydrase (27). The first is R1, the rate of exchange of CO2 and  at chemical equilibrium (Eq. 3), as shown in Eq. 5.

at chemical equilibrium (Eq. 3), as shown in Eq. 5.

|

(5) |

Here  is a rate constant for maximal interconversion of substrate and product,

is a rate constant for maximal interconversion of substrate and product,  is an apparent binding constant for substrate to enzyme, and [S] is the concentration of substrate, either CO2 or bicarbonate (27). The ratio

is an apparent binding constant for substrate to enzyme, and [S] is the concentration of substrate, either CO2 or bicarbonate (27). The ratio  is, in theory and in practice, equal to kcat/Km obtained by steady-state methods.

is, in theory and in practice, equal to kcat/Km obtained by steady-state methods.

A second rate determined by the 18O exchange method is RH2O, the rate of release from the enzyme of water-bearing substrate oxygen (Eq. 4). This is the component of the 18O exchange that is enhanced by exogenous proton donors (8,27). In such enhancements, the exogenous donor acts as a second substrate in the catalysis providing a proton (Eq. 4), and the resulting effect on 18O exchange is described by Eq. 6 below.

|

(6) |

Here  is the observed maximal rate constant for the release of

is the observed maximal rate constant for the release of  to bulk water caused by the addition of the buffer.

to bulk water caused by the addition of the buffer.  is an apparent binding constant of the buffer to the enzyme, [E] and [B] are the concentrations of total enzyme and total buffer, and

is an apparent binding constant of the buffer to the enzyme, [E] and [B] are the concentrations of total enzyme and total buffer, and  is the rate of release of

is the rate of release of  into solvent water in the absence of added buffer and represents the contribution to proton transfer from other sites on the enzyme or possibly solvent water itself.

into solvent water in the absence of added buffer and represents the contribution to proton transfer from other sites on the enzyme or possibly solvent water itself.

With the addition of derivatives of imidazole and pyridine at concentrations up to 200 mM, we have observed a weak inhibition of both R1 and RH2O. This is probably due to binding at or in the vicinity of the zinc in the manner found for the binding of imidazole to carbonic anhydrase I (29) and 4-MI to a mutant of HCA II (30). The binding constant Ki for this inhibition is generally >100 mM, indicating weak binding at the inhibitory site. Some exogenous donors (e.g., 1,2-dimethylimidazolium; 3,4-dimethylpyridinium) exhibited no inhibition. In each case of inhibition, a single value Ki described inhibition of both R1 and RH2O, as determined by these equations:

|

(7) |

The pH dependence of RH2O/[E] is often bell-shaped, consistent with the transfer of a proton from a single predominant donor to the zinc-bound hydroxide. In these cases, the pH profile is adequately fit by Eq. 8 in which kB is a pH-independent rate constant for proton transfer, and (Ka)donor and (Ka)ZnH2O are the noninteracting ionization constants of the proton donor BH of Eq. 4 and the zinc-bound water.

|

(8) |

RESULTS

Activation of catalysis

The effect of a series of imidazole and pyridine derivatives on catalysis by site-specific mutants of carbonic anhydrase (H64G, H64W, and W5A-H64W HCAII) was measured by the exchange of 18O between CO2 and water. We measured the effect of these potential proton donors on two aspects of the catalysis,  for hydration of CO2 (Eqs. 3 and 5) and the rate constant RH2O/[E] for the proton transfer-dependent release of

for hydration of CO2 (Eqs. 3 and 5) and the rate constant RH2O/[E] for the proton transfer-dependent release of  from the enzyme during catalysis (Eqs. 4 and 6) (27).

from the enzyme during catalysis (Eqs. 4 and 6) (27).

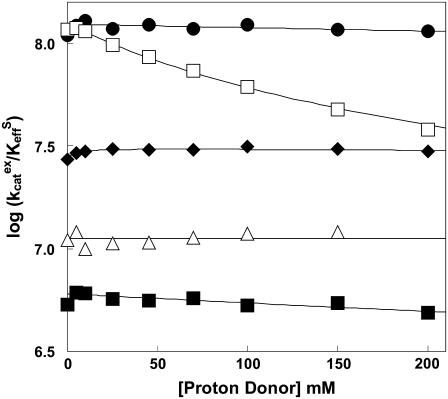

The values of  for hydration of CO2 catalyzed by H64G, H64W, and W5A-H64W HCA II were not activated by increasing concentrations (up to 200 mM) of the derivatives of imidazole and pyridine used (typical data shown in Fig. 1). This is consistent with the catalytic mechanism in which the conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate does not contain rate-contributing proton transfers. The maximal values of

for hydration of CO2 catalyzed by H64G, H64W, and W5A-H64W HCA II were not activated by increasing concentrations (up to 200 mM) of the derivatives of imidazole and pyridine used (typical data shown in Fig. 1). This is consistent with the catalytic mechanism in which the conversion of CO2 into bicarbonate does not contain rate-contributing proton transfers. The maximal values of  at 108 M−1 s−1 for catalysis by H64W HCA II (Fig. 1) were as great as that observed for wild-type enzyme (5). We sometimes observed a weak inhibition in

at 108 M−1 s−1 for catalysis by H64W HCA II (Fig. 1) were as great as that observed for wild-type enzyme (5). We sometimes observed a weak inhibition in  caused by addition of imidazole derivatives with values of the inhibition constant Ki between 150 mM and 250 mM. This effect has been observed by Elder et al. (30) for the binding of 4-MI to H64A HCA II as a second sphere ligand of the zinc. In such cases, the inhibition was taken into account in estimating

caused by addition of imidazole derivatives with values of the inhibition constant Ki between 150 mM and 250 mM. This effect has been observed by Elder et al. (30) for the binding of 4-MI to H64A HCA II as a second sphere ligand of the zinc. In such cases, the inhibition was taken into account in estimating  , as described in Methods (Eq. 7).

, as described in Methods (Eq. 7).

FIGURE 1.

The dependence of  (M−1 s−1) for hydration (S = CO2, Eq. 5) catalyzed by H64W HCA II on the concentration of (•) 1,2-dimethylimidazole at pH 8.3; (□) 4-methylimidazole at pH 7.9; (♦) 3,4-dimethylpyridine at pH 6.7; (▵) 4-methylpyridine at pH 6.1; and (▪) 3-methylpyridine at pH 5.8. Data were obtained by 18O exchange using solutions at 25°C containing 25 mM of all species of CO2, with ionic strength maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M with sodium sulfate. No other buffers were added.

(M−1 s−1) for hydration (S = CO2, Eq. 5) catalyzed by H64W HCA II on the concentration of (•) 1,2-dimethylimidazole at pH 8.3; (□) 4-methylimidazole at pH 7.9; (♦) 3,4-dimethylpyridine at pH 6.7; (▵) 4-methylpyridine at pH 6.1; and (▪) 3-methylpyridine at pH 5.8. Data were obtained by 18O exchange using solutions at 25°C containing 25 mM of all species of CO2, with ionic strength maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M with sodium sulfate. No other buffers were added.

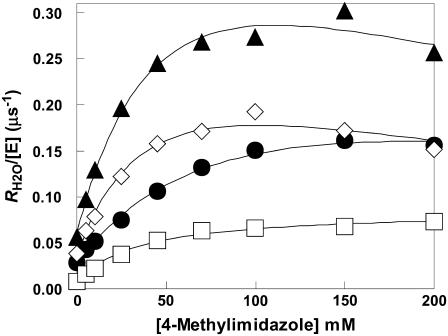

The addition of these compounds caused a saturable increase in RH2O/[E]. Typical data for 4-MI are shown in Fig. 2, demonstrating the greater enhancement of H64W compared with H64G HCA II and W5A-H64W HCA II. This activation can be fit by the parameters of Eq. 6 described for the activation of H64G HCA II in the legend of Fig. 2. These activations of RH2O/[E] typically showed an H/D solvent isotope effect indicating greater catalysis when measured in H2O than in D2O. A solvent hydrogen isotope effect between 1.7 and 2.3 is shown in Fig. 2 for the activation of H64G HCA II by 4-MI.

FIGURE 2.

Activation of  by 4-methylimidazole of 18O exchange catalyzed by (▴) H64W; (⋄) W5A-H64W; (•) H64G; and (□) H64G HCA II in 98% D2O. Solutions contained 25 mM of all species of CO2 at 25°C and pH or pD 7.8 (uncorrected pH meter reading). The total ionic strength of solution was maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of Na2SO4. For H64G HCA II in H2O, a fit of these data using Eq. 6 yields

by 4-methylimidazole of 18O exchange catalyzed by (▴) H64W; (⋄) W5A-H64W; (•) H64G; and (□) H64G HCA II in 98% D2O. Solutions contained 25 mM of all species of CO2 at 25°C and pH or pD 7.8 (uncorrected pH meter reading). The total ionic strength of solution was maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of Na2SO4. For H64G HCA II in H2O, a fit of these data using Eq. 6 yields  and

and  . For the data in D2O, a fit of Eq. 6 yields

. For the data in D2O, a fit of Eq. 6 yields  and

and  .

.

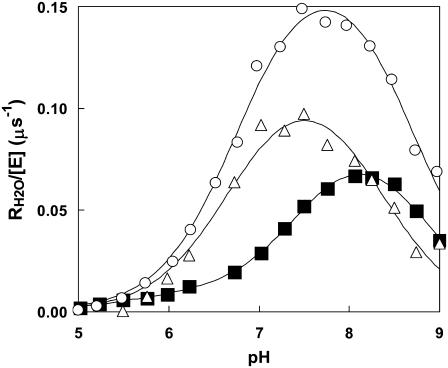

The data of Fig. 3 show the pH profiles of RH2O/[E] catalyzed by H64W HCA II in the presence and absence of a near-saturating level, 75 mM, of the activator 4-MI. The values of RH2O in the absence of 4-MI (or other added buffers) are presumably due to proton-donating residues near the active-site cavity (31). The plot in Fig. 3 representing the difference between RH2O/[E] in the presence and absence of 4-MI can be fit by Eq. 8, which describes activation as a single proton transfer between noninteracting donor and acceptor groups. This difference plot represents the activation of H64W HCA II by 4-MI and is fit by a value of  with pKa values of 6.7 ± 0.1 and 8.3 ± 0.1 (Fig. 3). These are to be compared with the pKa of 7.3 ± 0.1 measured for the zinc-bound water determined from the pH profile of

with pKa values of 6.7 ± 0.1 and 8.3 ± 0.1 (Fig. 3). These are to be compared with the pKa of 7.3 ± 0.1 measured for the zinc-bound water determined from the pH profile of  catalyzed by H64W HCA II (data not shown), and with the solution pKa of 7.9 for 4-MI. The data of Figs. 2 and 3 confirm that the activation observed for 4-MI is consistent with proton transfer. The rate constants

catalyzed by H64W HCA II (data not shown), and with the solution pKa of 7.9 for 4-MI. The data of Figs. 2 and 3 confirm that the activation observed for 4-MI is consistent with proton transfer. The rate constants  and kB were determined by fitting (Enzfitter, Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) of Eqs. 6–8 to data for each activator such as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

and kB were determined by fitting (Enzfitter, Biosoft, Cambridge, UK) of Eqs. 6–8 to data for each activator such as shown in Figs. 2 and 3.

FIGURE 3.

The dependence on pH of the rate constant for 18O exchange RH2O/[E] catalyzed by H64W HCA II and measured in the absence of buffer (▪), and in the presence of 75 mM 4-MI (○). Data representing the difference between these two sets are shown (Δ). Data were obtained at 25°C using solutions containing 25 mM of all species of CO2. Ionic strength was maintained at a minimum of 0.2 M by addition of sodium sulfate. The solid line for the difference data was obtained by a fit to Eq. 8 resulting in  for the proton donor(s) was 8.3 ± 0.1 and pKa for the zinc-bound water was 6.7 ± 0.1.

for the proton donor(s) was 8.3 ± 0.1 and pKa for the zinc-bound water was 6.7 ± 0.1.

Free energy plots were constructed for kB for catalysis by H64W and H64G HCA II. In the plots of Fig. 4, pKa(ZnH2O) was determined from the pH profile of kcat/Km for hydration of CO2, which is fit to a single ionization; the value of pKa(ZnH2O) was 7.3 ± 0.1 for H64W HCA II and 7.2 ± 0.1 for H64G HCA II. In this plot, the pKa of the donor was taken as its solution pKa; this value of pKa was generally in agreement within standard errors with the value determined from pH profiles such as shown in Fig. 3. The values of kB were determined from plots such as in Figs. 2 and 3. This sometimes required taking into account a small extent of inhibition, which was observed at higher levels of the derivatives of imidazole and pyridine, as described in Methods (Eq. 7). Parameters from a fit of the Marcus equation to kB are given in Table 2 (see Discussion). There is insufficient data at larger values of ΔpKa in Fig. 4 to comment on the existence of an inverted region.

TABLE 2.

Constants of the Marcus theory for proton transfer in catalysis by variants of carbonic anhydrase

| Enzyme |

(kcal/mol) (kcal/mol) |

wr (kcal/mol) | wp (kcal/mol) |

|---|---|---|---|

| H64W HCA II | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 8.0 ± 0.2 | 8.2 ± 0.1 |

| H64G HCA II | 0.3 ± 0.1 | 8.5 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.1 |

X-ray crystallography

The crystal structures of the site-specific mutants H64W, W5A-H64W, and W5A-H64W with bound 4-MI were determined to 1.8 Å resolution. The crystals were isomorphous, monoclinic P21, with mean unit cell dimensions: a = 42.1 ± 0.2, b = 41.4 ± 0.1, and c = 71.9 ± 0.1 Å; and β = 103.9 ± 0.2°. A summary of the data set statistics is given in Table S1 of the accompanying Supplementary Material. The backbone conformations of all three structures are very similar; when superimposed onto the structure of wild-type HCA II (PDB accession code: 2CBA), the structures of H64W and W5A-H64W each gave an average root mean-square deviation of 0.3 ± 0.1 Å for Cα atoms. Final model refinement statistics are given in Table 1. Attempts to observe binding of imidazole, 4-methylimidazole, and 3,5-dimethylpyridine to H64W HCA II, and imidazole and 3,5-dimethylpyridine to W5A-H64W HCA II, were unsuccessful. These attempts were done by cocrystallization and soaking crystals in solutions containing these proton donors.

Coordinates and structure factors for H64W, W5A-H64W, and W5A-H64W with bound 4-MI have been deposited with the Protein Data Bank (PDB; http://www.rcsb.org) with the accession codes 2FNK, 2FNM, and 2FNN, respectively.

Active-site architecture of HCA II mutants

The single mutant, H64W HCA II, was structurally similar to wild-type, with the exception of active site residues Trp-5 and Trp-64. These two residues are in close proximity to each other and appear to loosely π-stack with each other in H64W HCA II (Fig. 5 A). The side chains of Trp-5 and Trp-64 were somewhat disordered as reflected in the observed B-factors (∼25 and ∼30 Å2, respectively) compared to all side chains (∼16 Å2) and by visual inspection of the electron density (Table 1, Fig. 5 A). This apparent disorder could be due to steric hindrance between the residues or dynamic movement of these two bulky hydrophobic side chains. Replacement of Trp-5 with Ala led to significantly improved order in the electron density for the side chain Trp-64 in the W5A-H64W crystal structure, making it possible to place the side chain unequivocally (Fig. 5 B).

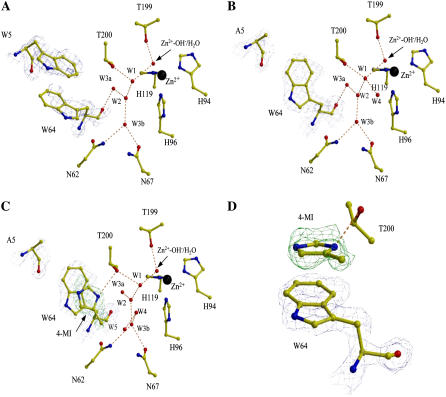

FIGURE 5.

Active sites of (A) H64W; (B) W5A-H64W; (C) W5A-H64W HCA II in complex with 4-MI; and (D) a closeup view of 4-MI binding site in W5A-H64W HCA II. Panels A–C are shown in the same orientation. Side chains, water molecules, ligands, and ions are as labeled. 2Fo-Fc electron density is shown in blue (amino-acid residues) or green (4-MI), and contoured at 1.0 σ in panel A and 1.5 σ in panels B and C. The figure was generated and rendered with BobScript and Raster3D (42,43).

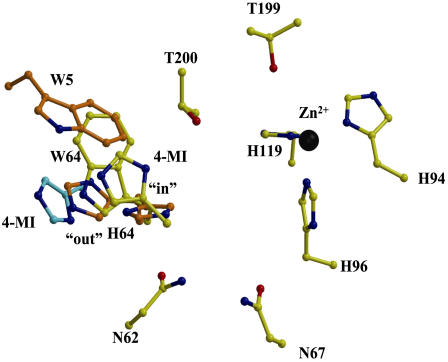

In the cocrystals of W5A-H64W HCA II with 4-MI, additional Fo-Fc electron density corresponding to 4-MI ∼3.5 Å from Trp-64 was observed. The 4-MI π-stacked with the side chain of Trp-64 and made a hydrogen bond between the N3 atom and Oγ1 of Thr-200 (Fig. 5, C and D). The 4-MI is ∼8 Å away from the zinc ion in the active site (Fig. 5 C). It is noteworthy that in both H64W and W5A-H64W HCA II, the side chain of Trp-64 seems to occupy a similar conformation to the inward position of His-64 in wild-type HCA II (Fig. 6) (9,10). The 4-MI molecule bound in W5A-H64W HCA II adopts a position that seems to straddle the inward and outward positions of His-64 in wild-type HCA II (Fig. 6) (9,10). This shows 4-MI bound at Trp-64 closer by ∼4 Å than when bound at Trp-5 in H64A HCA II (Fig. 6) (13).

FIGURE 6.

Superimposition of active site residues of (yellow) W5A-H64W HCA II showing the binding site of 4-MI, and (orange) the side chains of His-64 and Trp-5 in HCA II (PDB accession code: 1TBT (10)) showing the inward and outward conformations of His-64, and (cyan) the binding site of 4-MI associated with the side chain of Trp-5 in H64A HCA II (PDB accession code: 1MOO; (16)). The figure was generated and rendered with BobScript and Raster3D (42,43).

The core active-site solvent network observed in wild-type HCA II (10) consisting of the Zn-OH−/H2O, W1, W2, W3a, and W3b, was conserved in the mutants of HCA II in Fig. 5, A–C. In H64W HCA II and in W5A-H64W HCA II without 4-MI, solvent molecule W3a is within hydrogen-bonding distance (2.9 and 2.8 Å, respectively) of the backbone O of Trp-64 (Fig. 5, A and B). This is in contrast with wild-type structures where the distances between W2, W3a, and W3b are all too long (∼3.5 Å) to constitute viable hydrogen bonds with His-64 (10).

DISCUSSION

A goal of this study is to estimate regions within the active-site cavity from which protons can efficiently be transferred to the zinc-bound hydroxide during catalysis by HCA II. Small molecule rescue provides a probe of proton transfer sites; after entering the active-site cavity, an exogenous proton donor/acceptor must achieve an appropriate location and orientation, and perhaps participate in hydrogen-bonding with water or amino-acid side chains, before the proton transfer can occur. We know from previous studies of a number of sites within the active-site cavity where 4-MI binds but does not contribute to proton transfer: 1), at the side chain of Trp-5 in H64A HCA II ∼12 Å from the zinc (12,13); 2), in a pocket formed by the side chains of Glu-69, Ile-91, and Asp-72 ∼13 Å from the zinc (16); and 3), as a second-shell ligand of the metal in CO(II)-substituted H64A HCA II, a site determined to be inhibitory to catalysis (30).

Since these binding sites for 4-MI were nonproductive in proton transfer, we used another strategy and constructed a binding site for small molecule rescue near the site of His-64, the proton shuttle of wild-type enzyme. We have examined a variant of HCA II with His-64 replaced by Trp. Previous studies had emphasized replacement of His-64 with Ala (12,13); this replacement with Trp is unique. The crystal structure of H64W HCA II is superimposable with wild-type and shows the extension into the active-site cavity of the indole ring of Trp-64 (Fig. 5 A). The strategy is based on the expectation that the proton donor 4-MI will bind to Trp-64 ∼8 Å from the zinc and will contribute to proton transfer (to an extent larger than for H64G) being at a location that is near the proton shuttle residue His-64 in the inward conformation (9,10). Trp-64 itself is not a proton transfer residue.

Small molecule rescue of catalysis

The expected activation has been observed. A series of experiments show the enhancement of catalysis by H64W HCA II upon addition of exogenous proton donors. These experiments include saturable activation of the second stage of catalysis (Eq. 4; Fig. 2), solvent H/D isotope effects on maximal activation near 2 (Fig. 2), pH profiles consistent with proton transfer between exogenous donors/acceptors and the zinc-bound aqueous ligand (Fig. 3), observation of a much smaller activation with H64G than H64W HCA II (Fig. 2), and finally the observation by x-ray crystallography of the binding of 4-MI associated in a π-stacked interaction with the indole side chain of Trp-64 in W5A-H64W HCA II (Figs. 5 and 6). This is reasonable evidence that activation by 4-MI, and most likely the other activators of Fig. 4, occurs in part by binding to Trp-64 with subsequent participation in proton transfer.

It is interesting that x-ray crystallography did not show the binding of exogenous donors to H64W HCA II, the mutant that was activated by these donors. However, the binding of 4-MI to W5A-H64W HCA II was observed even though this mutant was activated to a lesser extent (Fig. 2). The distance between the indole rings of Trp-5 and Trp-64 in H64W CA II is ∼3.5 Å, too close for 4-MI to bind between them without steric clashes. However, this distance between the two rings is essentially what is observed in the base-stacking of B-DNA. Hence it is conceivable that 4-MI could bind like a DNA intercalator to open the gap between Trp-5 and Trp-64 and sandwich between them. However, we did not observe such a structure in crystals of H64W in the presence of 4-MI and it is possible that the protein backbone structure is too rigid to allow such a structural rearrangement to occur.

The lack of an observed binding site for 4-MI in the crystal structure of H64W HCA II might be related to the conformational flexibility and disorder of the side chain of Trp-64 in this mutant. The electron density corresponding to the side chain of Trp-64 in H64W HCA II is smeared and has a mean thermal B-factor near 30 Å2, which is twice as large as the other side chains in the active site and therefore can be interpreted to reflect conformational mobility of this side chain (Fig. 5 A). This mobility may be necessary to achieve a conformation from which proton transfer can proceed, whereas a more constrained conformation that is not favorable for proton transfer would be associated with lower catalytic activity. Interestingly, Trp-64 in the double mutant W5A-H64W HCA II without and with 4-MI bound is more ordered with mean thermal B-factors near 16 and 14 Å2, respectively (Fig. 5, B and C; Table 1). This mutant is weakly activated compared with H64W HCA II (Fig. 2). Conformational mobility appears in several studies to be associated with efficient proton transfer in catalysis by carbonic anhydrases (9,10,32,33), and these data are yet another example.

This study locates a binding site for small molecule rescue of carbon anhydrase, the first case that is demonstrated by the decrease of activation when the binding site is altered through mutagenesis. Also, this site is located in the vicinity of His-64 of the wild-type enzyme (Fig. 6), not at more distant or closer sites, suggesting a significant distance-dependence. Table 3 places these results in the context of previous studies and provides a rough quantitation of the distance requirements for small molecule rescue of proton transfer in this system.

TABLE 3.

Rate constants for proton transfer from various sites in human carbonic anhydrase II and site-specific mutants

| Enzyme | Donor | Distance to Zn* (Å) |  |

Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| H64A | 4-MI | 4.8 | Inhibitory | 30 |

| H64A-T200H | His-200 | 5.2 | ∼300 | 41 |

| H64A-N67H | His-67 | 6.6 | 200 | 10 |

| Wild-type | His-64 | 7.5 | 800 | 13 |

| H64W | 4-MI† | 8.0 | 130 | This work |

| H64A-N62H | His-62 | 8.2 | ∼30 | 10 |

| H64A | 4-MI‡ | 12.0 | 0 | 12 |

Distance between the zinc and N1 or N3 of the imidazole donor.

4-MI bound at Trp-64.

4-MI bound at Trp-5.

Free energy plots

Interpretation of the free energy plots in Fig. 4 is based in part on their curvature and their similarity to the curvature of free energy plots in nonenzymic, bimolecular proton transfer between electronegative atoms, interpreted as facile proton transfer with low intrinsic barrier (18). In this respect, the properties of the nonenzymic proton transfers are similar to those accompanying catalysis by carbonic anhydrase. The most straightforward quantitation of the barriers is through application of classical Marcus theory applied to proton transfer, which has been explored in the case of nonenzymic transfers (18).

In Marcus theory applied to proton transfer, the observed overall activation energy for proton transfer ΔG‡ is described in terms of the standard free energy of reaction ΔG° and an intrinsic kinetic barrier  , which is the value of ΔG‡ when ΔG° = 0, that is, when the transfer is free of thermodynamic influences and represents a pure or “intrinsic” energy barrier (17,18). The Marcus equation is further modified to describe proton transfers in which there is a component of the observed activation barrier that does not depend on ΔG° for the reaction. This component is called the work term “wr” for the forward direction (dehydration here). Similarly, “wp” is the work term required for the reverse reaction. In nonenzymic, bimolecular proton transfers, the work term is considered part of the free energy of reaction needed to bring the reactants together and form the reaction complex with associated solvation changes before proton transfer (19). The Marcus equation then becomes

, which is the value of ΔG‡ when ΔG° = 0, that is, when the transfer is free of thermodynamic influences and represents a pure or “intrinsic” energy barrier (17,18). The Marcus equation is further modified to describe proton transfers in which there is a component of the observed activation barrier that does not depend on ΔG° for the reaction. This component is called the work term “wr” for the forward direction (dehydration here). Similarly, “wp” is the work term required for the reverse reaction. In nonenzymic, bimolecular proton transfers, the work term is considered part of the free energy of reaction needed to bring the reactants together and form the reaction complex with associated solvation changes before proton transfer (19). The Marcus equation then becomes

|

(9) |

This expression assumes that the work terms wr and wp as well as the intrinsic energy barrier  do not vary for proton transfer between the series of homologous proton donors to which the equation is fit. Catalysis by variants of HCA III (34) and HCA II (12) has previously been interpreted in terms of the Marcus formalism.

do not vary for proton transfer between the series of homologous proton donors to which the equation is fit. Catalysis by variants of HCA III (34) and HCA II (12) has previously been interpreted in terms of the Marcus formalism.

The solid lines of Fig. 4 are fits of this Marcus theory describing activation of catalysis (kB of Eq. 8) by proton transfer from a series of imidazole and pyridine derivatives. The corresponding parameters for the fit to the Marcus equation (Eq. 9) (Enzfitter, Biosoft) are given in Table 2.

For the activation of the variants of carbonic anhydrase in Table 2, the values of the Marcus parameters show rather small values of the intrinsic kinetic barrier  and large values of the work terms wr and wp, consistent with previous applications of Marcus theory to catalysis by carbonic anhydrase (12,34). The implications for catalysis of a low intrinsic barrier and large work functions have been discussed previously (19,34). These are viewed as estimates and limited by applicability of the classical Marcus theory, which is the most straightforward although certainly not the only interpretation of free energy plots such as Fig. 4. Braun-Sand et al. (35) have analyzed proton transfer in carbonic anhydrase III using an empirical valence bond approach to a multistate model with larger estimates of the intrinsic barrier.

and large values of the work terms wr and wp, consistent with previous applications of Marcus theory to catalysis by carbonic anhydrase (12,34). The implications for catalysis of a low intrinsic barrier and large work functions have been discussed previously (19,34). These are viewed as estimates and limited by applicability of the classical Marcus theory, which is the most straightforward although certainly not the only interpretation of free energy plots such as Fig. 4. Braun-Sand et al. (35) have analyzed proton transfer in carbonic anhydrase III using an empirical valence bond approach to a multistate model with larger estimates of the intrinsic barrier.

What is new in this work is the comparison of the parameters of the Marcus equation for the small molecule rescue of H64W and H64G. It is apparent from the data in Table 2 that proton transfer from exogenous donors in H64G HCA II has larger values of the work functions wr and wp compared with those of H64W HCA II; however, the Marcus intrinsic barriers  are the same for both. This is evident from observation of the similar curvature of the plots in Fig. 4; the curvature of these plots is a direct measure of the Marcus intrinsic barrier:

are the same for both. This is evident from observation of the similar curvature of the plots in Fig. 4; the curvature of these plots is a direct measure of the Marcus intrinsic barrier:  . This suggests that the presumed binding in small-molecule rescue to the side chain of Trp-64, as observed with 4-MI (Figs. 5 and 6), allows for more facile formation of a proton transfer pathway through water structure and positioning of proton donors compared with binding sites in H64G HCA II, and that this is reflected in the work functions wr and wp rather than in the intrinsic Marcus barrier itself. There may be other binding sites for 4-MI within the active-site cavity that can transfer protons to the zinc-bound hydroxide, as indicated by activation of H64G, but the presence of Trp-64 has enhanced the concentration of proton donors in a position for facile proton transfer.

. This suggests that the presumed binding in small-molecule rescue to the side chain of Trp-64, as observed with 4-MI (Figs. 5 and 6), allows for more facile formation of a proton transfer pathway through water structure and positioning of proton donors compared with binding sites in H64G HCA II, and that this is reflected in the work functions wr and wp rather than in the intrinsic Marcus barrier itself. There may be other binding sites for 4-MI within the active-site cavity that can transfer protons to the zinc-bound hydroxide, as indicated by activation of H64G, but the presence of Trp-64 has enhanced the concentration of proton donors in a position for facile proton transfer.

In the case of proton transfer by carbonic anhydrase, wr can reasonably be expected to include the energy to orient the proton donor and to form not only the hydrogen-bonded water bridge but also the water structure in the active-site cavity that interacts with the bridge and with the residues of the cavity (19). The large value of wr found for catalysis by carbonic anhydrase does not necessarily indicate the presence of a high energy intermediate or specific active-site conformation (36). It should be noted that the proton transfer step alternates in the mechanism with the interconversion of CO2 and bicarbonate (Eqs. 1 and 2), and that the diffusion of these reactants/products into and out of the active site would surely disrupt solvent structure.

Although 4-MI binds to the side chain of Trp-64, it does not have the efficiency of His-64 in proton transfer. Fig. 3 shows that the maximal rate constant for proton transfer from 4-MI bound at Trp-64 is ∼0.13 s−1, to be compared with 0.8 s−1 for His-64 in wild-type HCA II (13). The distance of ∼7 Å between His-64 and the zinc-bound water is a distance that can be spanned by two or perhaps three water molecules. In fact, this is what is observed with the ordered water molecules in the crystal structures (Fig. 5), and Table 3 gives an indication of the sensitivity of the system to the number of water molecules. These considerations appear to be consistent with recent computational estimates of how the efficiency of proton transfer in a model of carbonic anhydrase is dependent on the number of intervening water molecules (37–39). The ordered water in the crystal structures of carbonic anhydrase may not show the exact path for proton transfer but certainly offers important clues. Not surprisingly, evolution has placed the proton shuttle His-64 at an efficient location. A proton shuttle farther from the metal would be unfavorable in requiring alignment of many hydrogen-bonded water molecules, and closer to the metal would not be an efficient position to transfer protons out to solution, and might be inhibitory if too close to the metal.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

An online supplement to this article can be found by visiting BJ Online at http://www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Haiqian An for preparation of a site-specific mutant.

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health, grant No. GM 25154.

Abbreviations used: HCA II, isozyme II of human carbonic anhydrase; H64W HCA II, the site-specific mutant of HCA II with His-64 replaced by Trp; 4-MI, 4-methylimidazole.

References

- 1.Lindskog, S. 1997. Structure and mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. Pharmacol. Ther. 74:1–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Christianson, D. W., and C. A. Fierke. 1996. Carbonic anhydrase: evolution of the zinc binding site by nature and by design. Acounts Chem. Res. 29:331–339. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Northrop, D. B., and K. L. Rebholz. 1997. Kinetics of enzymes with iso-mechanisms: solvent isotope effects. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 342:317–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverman, D. N., and S. Lindskog. 1988. The catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase: implications of a rate-limiting protolysis of water. Acounts Chem. Res. 2:30–36. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simonsson, I., B. H. Jonsson, and S. Lindskog. 1979. A 13C nuclear-magnetic-resonance study of CO2-HCO3 exchange catalyzed by human carbonic anhydrase C at chemical equilibrium. Eur. J. Biochem. 93:409–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silverman, D. N., C. K. Tu, S. Lindskog, and G. C. Wynns. 1979. Rate of exchange of water from the active site of carbonic anhydrase C. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 101:6703–6740. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jonsson, B. H., H. Steiner, and S. Lindskog. 1976. Participation of buffer in catalytic mechanism of carbonic anhydrase. FEBS Lett. 64:310–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tu, C. K., D. N. Silverman, C. Forsman, B. H. Jonsson, and S. Lindskog. 1989. Role of histidine 64 in the catalytic mechanism of human carbonic anhydrase II studied with a site-specific mutant. Biochemistry. 28:7913–7918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair, S. K., and D. W. Christianson. 1991. Unexpected pH-dependent conformation of His-64, proton shuttle of carbonic anhydrase II. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:9455–9458. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher, Z., J. A. Hernandez Prada, C. K. Tu, D. Duda, C. Yoshioka, H. An, L. Govindasamy, D. N. Silverman, and R. McKenna. 2005. Structural and kinetic characterization of active-site histidine as a proton shuttle in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry. 44:1097–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venkatasubban, K. S., and D. N. Silverman. 1980. Carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase in mixtures of water and deuterium oxide. Biochemistry. 19:4984–4989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.An, H., C. K. Tu, D. Duda, I. Montanez-Clemente, K. Math, P. J. Laipis, R. McKenna, and D. N. Silverman. 2002. Chemical rescue in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrases II and III. Biochemistry. 41:3235–3242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duda, D., C. K. Tu, M. Qian, P. Laipis, M. Agbandje-McKenna, D. N. Silverman, and R. McKenna. 2001. Structural and kinetic analysis of the chemical rescue of the proton transfer function of carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry. 40:1741–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briganti, F., S. Mangani, P. Orioli, A. Scozzafava, G. Vernaglione, and C. T. Supuran. 1997. Carbonic anhydrase activators: x-ray crystallographic and spectroscopic investigations for the interaction of isozymes I and II with histamine. Biochemistry. 36:10384–10392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Temperini, C., A. Scozzafava, D. Vullo, and C. T. Supuran. 2006. Carbonic anhydrase activators. Activation of isoforms I, II, IV, VA, VII, and XIV with L- and D-phenylalanine and crystallographic analysis of their adducts with isozyme II: stereospecific recognition within the active site of an enzyme and its consequences for the drug design. J. Med. Chem. 49:3019–3027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Duda, D., L. Govindasamy, M. Agbandje-McKenna, C. K. Tu, D. N. Silverman, and R. McKenna. 2003. The refined atomic structure of carbonic anhydrase II at 1.05 Å resolution: implications of chemical rescue of proton transfer. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 59:93–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marcus, R. A. 1968. Theoretical relations among rate constants, barriers, and Bronsted slopes of chemical reactions. J. Phys. Chem. 72:891–899. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kresge, A. J. 1975. What makes proton transfer fast? Accounts Chem. Res. 8:354–360. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kresge, A. J., and D. N. Silverman. 1999. Application of Marcus rate theory to proton transfer in enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Methods Enzymol. 308:276–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tanhauser, S. M., D. A. Jewell, C. K. Tu, D. N. Silverman, and P. J. Laipis. 1992. A T7 vector optimized for site-directed mutagenesis using oligodeoxyribonucleotide cassettes. Gene. 117:113–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Khalifah, R. G., D. J. Strader, S. H. Bryant, and S. M. Gibson. 1977. Carbon-13 nuclear magnetic resonance probe of active-site ionizations in human carbonic anhydrase B. Biochemistry. 16:2241–2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McPherson, A. 1982. Preparation and Analysis of Protein Crystals. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 23.Otwinoski, Z., and W. Minor. 1997. Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276:307–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jones, T. A., J. Y. Zhou, S. W. Cowan, and M. Kjeldgaard. 1991. Improved methods for building protein models in electron density maps and the location of errors in these models. Acta Crystallogr. 47:110–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunger, A. T., P. D. Adams, P. D. Clore, W. L. DeLano, P. Gros, R. W. Grosse-Kunstleve, J. S. Jiang, J. Kuszewski, M. Nilges, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, L. M. Rice, T. Simonson, and G. L. Warren. 1998. Crystallography and NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 54:905–921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Håkansson, K., M. Carlsson, L. A. Svensson, and A. Liljas. 1992. Structure of native and apo carbonic anhydrase II and structure of some of its anion-ligand complexes. J. Mol. Biol. 227:1192–1204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Silverman, D. N. 1982. Carbonic anhydrase: oxygen-18 exchange catalyzed by an enzyme with rate-contributing proton-transfer steps. Methods Enzymol. 87:732–752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koening, S. H., and R. D. Brown. 1981. Carbonic anhydrase catalyzed exchanged of labeled nuclei in the CO2-bicarbonate-solvent system. Biophys. J. 35:59–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kannan, K. K., M. Petef, K. Fridborg, H. Cid-Dresdner, and S. Lovgren. 1977. Structure and function of carbonic anhydrases. Imidazole binding to human carbonic anhydrase B and the mechanism of action of carbonic anhydrases. FEBS Lett. 73:115–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Elder, I., C. K. Tu, L. J. Ming, R. McKenna, and D. N. Silverman. 2005. Proton transfer from exogenous donors in catalysis by human carbonic anhydrase II. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 437:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian, M., J. N. Earnhardt, N. R. Wadhwa, C. K. Tu, P. J. Laipis, and D. N. Silverman. 1999. Proton transfer to residues of basic pKa during catalysis by carbonic anhydrase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1434:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iverson, T. M., B. E. Alber, C. Kisker, J. G. Ferry, and D. C. Rees. 2000. A closer look at the active site of γ-class carbonic anhydrases: high-resolution crystallographic studies of the carbonic anhydrase from Methanosarcina thermophila Biochemistry. 39:9222–9231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jude, K. M., S. K. Wright, C. K. Tu, D. N. Silverman, R. E. Viola, and D. W. Christianson. 2002. Crystal structure of F65A/Y131C-methylimidazole carbonic anhydrase V reveals architectural features of an engineered proton shuttle. Biochemistry. 41:2485–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverman, D. N., C. K. Tu, X. Chen, S. M. Tanhauser, A. J. Kresge, and P. J. Laipis. 1993. Rate-equilibria relationships in intramolecular proton transfer in human carbonic anhydrase III. Biochemistry. 32:10757–10762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Braun, S., M. Strajbl, and A. Warshel. 2004. Studies of proton translocations in biological systems: simulating proton transport in carbonic anhydrase by EVB-based models. Biophys. J. 87:2221–2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim, Y., D. G. Truhlar, and M. M. Kreevoy. 1991. An experimentally based family of potential energy surfaces for hydride transfer between NAD+ analogues. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 113:7837–7847. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cui, Q., and M. Karplus. 2003. Is a proton wire concerted or stepwise? A model study of proton transfer in carbonic anhydrase. J. Phys. Chem. B. 107:1071–1078. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lu, D., and G. A. Voth. 1998. Molecular dynamics simulations of human carbonic anhydrase II: insights into experimental results and the role of solvation. Proteins Struct. Funct. Genetics. 33:119–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riccardi, D., P. Schaefer, Y. Yang, H. B. Yu, N. Ghosh, X. Prat-Resina, P. Konig, G. H. Li, D. G. Xu, H. Guo, M. Elstner, and Q. Cui. 2006. Development of effective quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical QM/MM. Methods for complex biological processes. J. Phys. Chem. B. 110:6458–6469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laskowski, R. A., M. W. MacArthur, D. S. Moss, and J. M. Thornton. 1993. PROCHECK: a program to check the stereochemical quality. J. Appl. Cryst. 26:283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhatt, D., C.K. Tu, Z. Fisher, J.A. Hernandez-Prada, R. McKenna, and D.N. Silverman. Proton transfer in a Thr200His mutant of human carbonic anhydrase II. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinformat. 61: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Merrit, E., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Raster3D: photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esnouf, R. M. 1999. Further additions to MolScript version 1.4, including reading and contouring of electron-density maps. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 55:938–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]