Abstract

Before new drugs for the treatment of inner ear disorders can be studied in controlled clinical trials, it is important that their pharmacokinetics be established in inner ear fluids. Microdialysis allows drug levels to be measured in perilymph without the volume disturbances and potential cerebrospinal fluid contamination associated with fluid sampling. The aims of this study were to show: (i) that despite low recovery rates from miniature dialysis probes, significant amounts of drug are removed from small fluid compartments, (ii) that dialysis sampling artifacts can be accounted for using computer simulations and (iii) that microdialysis allows quantification of the entry rates through the round window membrane (RWM) into scala tympani (ST). Initial experiments used microdialysis probes in small compartments in vitro containing sodium fluorescein. Stable concentrations were observed in large compartments (1000 μl) but significant concentration declines were observed in smaller compartments (100, 10 and 5.6 μl) comparable to the size of the inner ear. Computer simulations of these experiments closely approximated the experimental data. In in vivo experiments, sodium fluorescein 10 mg/ml and dexamethasone-dihydrogen-phosphate disodium salt 8 mg/ml were simultaneously applied to the RWM of guinea pigs. Perilymph concentration in the basal turn of ST was monitored using microdialysis. The fluorescein concentration reached after 200 min application (585 ± 527 μg/ml) was approximately twice that of dexamethasone phosphate (291 ± 369 μg/ml). Substantial variation in concentrations was found between animals by approximately a factor of 34 for fluorescein and at least 41 for dexamethasone phosphate. This is, to a large extent, thought to be the result of the RWM permeability varying in different animals. It was not caused by substance analysis variations, because two different analytic methods were used and the concentration ratio between the two substances remained nearly constant across the experiments and because differences were apparent for the repeated samples obtained in each animal. Interpretation of the results using computer simulations allowed RWM permeability to be quantified. It also demonstrated, however, that cochlear clearance values could not be reliably obtained with microdialysis because of the significant contribution of dialysis to clearance. The observed interanimal variation, e.g., in RWM permeability, is likely to be clinically relevant to the local application of drugs in patients.

Keywords: Round window membrane, Permeability, Pharmacokinetics, Inner ear, Microdialysis, Perilymph, Drug delivery, Dexamethasone, Steroid

1. Introduction

In recent years, an increasing interest in local drug application to the round window membrane (RWM) has emerged. Substances have been shown to enter scala tympani and from there are distributed in the inner ear (Goycoolea, 2001). Recent pharmacokinetic studies have shown that substances applied locally to the RWM produce significantly higher drug levels in the inner ear fluids compared to systemic applications (Bachmann et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003a; Parnes et al., 1999). Thus, applying drugs locally may avoid potential systemic complications and side effects.

Glucocorticoids have been shown to be able to therapeutically influence various disorders associated with a disturbance of inner ear homeostasis, although the specific mechanisms are not completely resolved (Trune, 2006). There are a growing number of clinical reports with regard to local treatments with corticosteroids in cases of acute hearing loss of various causes (Chandrasekhar, 2001; Gian-oli and Li, 2001; Gouveris et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2004; Kopke et al., 2001; Lautermann et al., 2005; Lefebvre and Staecker, 2002; Plontke et al., 2005; Silverstein et al., 1996; Parnes et al., 1999), of Meniere’s disease (Itoh and Sakata, 1991; Sennaroglu et al., 2001; Shea and Ge, 1996; Silverstein et al., 1998) and of tinnitus (Cesarani et al., 2002; Coles et al., 1992; Sakata et al., 1997; Shulman and Goldstein, 2000; Silverstein et al., 1996). In addition, a number of investigational drugs show promising results with respect to protection when locally applied to the RWM (Li et al., 2001; Chen et al., 2003b; Hight et al., 2003; Keithley et al., 1998). However, no drugs are yet approved for local application to the round window membrane for a specific inner ear indication and success rates in clinical reports vary considerably.

Before new drugs can be approved for clinical use, preclinical studies are necessary. This includes determining the time course and total dose of the drug within the inner ear fluids. A critically important factor in experimental studies of inner ear pharmacokinetics is the method of fluid sampling used. It has been shown that the act of aspirating a perilymph sample can markedly influence the concentration of the drug in the inner ear fluids. As a result, sample concentrations may not always be a good indicator of the drug level at the site prior to sampling (Salt et al., 2003; Salt and Plontke, 2005; Scheibe et al., 1984).

In contrast, with microdialysis it is possible to measure substances without taking fluid samples, which is especially relevant to small volume compartments such as the inner ear. In vivo microdialysis has been used for more than a decade for clinical and preclinical research especially in the central nervous system (Elmquist and Sawchuk, 1997; Ungerstedt, 1991). Apart from its application to neurochemistry and neurophysiology in studying neurotransmitter release, uptake and metabolism, microdialysis has increasingly been used to address pharmacokinetic questions related to drug distribution and metabolism (de Lange et al., 2000; Elmquist and Sawchuk, 1997). In the peripheral auditory system, microdialysis has been used to measure the concentration of neurotransmitters (Hoya et al., 2001; Jager et al., 2000; Matsuda et al., 1998), urea (Hunter et al., 2003) and for pharmacokinetic studies after round window drug delivery of gentamicin (Hibi et al., 2001).

The advantages of microdialysis for pharmacokinetic studies in the inner ear include: (i) the use of repeated measurements allowing the drug time course to be determined, (ii) prevention of artifacts from perilymph volume loss through leaks, and (iii) limited disturbance of perilymph composition due to the low amount of drug recovery.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Microdialysis

Microdialysis has been applied to a variety of tissues including the measurement of drugs in the perilymphatic space of the cochlea (Hibi et al., 2001; Hunter et al., 2003; Plock and Kloft, 2005). A microdialysis probe consists of an inner tube and an outer tube that has a semipermeable membrane on its distal tip. In an experiment the inlet and the outlet on the proximal end of the probe are connected with tubing to a syringe mounted on a perfusion pump and a collecting vial, respectively. During the perfusion, a physiological buffered salt solution is driven through the inlet into the inner tube, crosses the tip with the dialysis membrane and leaves the outer tube through the outlet. The transport of molecules across the semipermeable membrane of the tip during the perfusion is driven by passive diffusion and can be described by the Fick equation. The molecules within the extracellular fluid diffuse across the semipermeable membrane into the perfusion fluid along their concentration gradient. The perfusion fluid (dialysate) can be collected and analysed to identify or quantify molecules that are present in the extracellular environment. It is also possible however to use this method to deliver substances to the extracellular environment. For that purpose a substance is added to the perfusate and then diffuses through the semipermeable membrane into the surrounding fluids (Plock and Kloft, 2005; Ungerstedt, 1991).

2.2. In vitro studies

Horizontal single chamber tubular compartments of different sizes were used to perform microdialysis experiments in vitro. Acrylic glass reservoirs with volumes of 1000, 100, 10 and 5.6 μl were produced at an in house workshop facility. Using appropriate tubing, the inlet ports of microdialysis probes (CMA/11 14/01/Cuprophane, CMA/Microdialysis AB, Stockholm, Sweden and MAB 4 Cuprophane, TSE, Bad Homburg, Germany) were connected to a syringe pump and the outlet ports connected to a fraction collector. A microdialysis probe was then inserted under microscope and micromanipulator control into the reservoir that was filled with sodium fluorescein (1 mg/ml, Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany). The linear flow microdialysis probes with a 6-kDa molecular mass cutoff, membrane length of 1 mm and external diameter of 0.24 mm were perfused with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at a rate of 2 μl/min (CMA/102 syringe pump). Dialysate samples were collected into plastic vials, using a refrigerated fraction collector (CMA/170) at 8.5 min intervals for up to 68 min. The sampling time interval was dependent upon the combined dead volume of the microdialysis probe, the outlet tubing and the cannula of the fraction collector. Samples were stored at -20°C for no longer than 14 days before analysis.

2.3. Assay of sodium fluorescein

The concentration of fluorescein in the dialysate samples was assayed using a fluorescence plate reader (Tecan Fluorescence Reader; Tecan Deutschland GmbH, Crailsheim, Germany) at an excitation wavelength of 485 nm and emission of 535 nm. Samples were diluted with PBS to 100 μl, and fluorescein was quantified in 100 μl aliquots using a calibration curve constructed for each experiment over the range of 10-1000 ng/ml.

2.4. Evaluation of in vitro dialysis probe recovery rate for sodium fluorescein

The recovery rate (fractional recovery) can be considered as a measure for the individual probe in respect to removing substance from a solution. Individual probes were immersed in 1 ml of unstirred or stirred fluorescein (1 mg/ml in PBS) in cubic reservoirs and perfused with PBS at a rate of 2 μl/min for 68 min. The recovery was calculated by dividing the measured concentration in the microdialysis sample by the initial reservoir concentration. The recovery rates measured in unstirred and stirred reservoirs were nearly identical (3.03% ± 0.27 and 2.91% ± 0.29, respectively).

2.5. Animal experiments

Animal experiments were approved by the animal studies committee of the University of Tübingen (number HN1/02). Fifteen specific pathogen free guinea pigs (weight: 280-550 g, Charles River, Kißlegg, Germany) were anesthetized with 6 mg/kg xylazine (Bayer, Leverkusen, Germany), 100 mg/kg ketamine hydrochloride (Pharmacia & Upjohn, Erlangen, Germany) and 0.2 mg/kg atropine sulphate (Braun, Melsungen, Germany). The trachea was cannulated and the body temperature was maintained at 37.5°C with a temperature controlled heating blanket. The animal was mounted in a head-holder, the auditory bulla was exposed by a ventrolateral approach and was opened to expose the cochlea. The mucosa was removed from the surface of the cochlea and the bone was allowed to dry. The insertion site for the microdialysis probe in the basal turn of scala tympani was coated with a thin layer of cyanoacrylate glue (Aesculap, Tuttlingen, Germany). A small hole was drilled into the bone overlying scala tympani with a 0.25-mm steel drill at a distance of 1.3-1.9 mm (mean: 1.6, SD: 0.2) from the round window. The microdialysis probe was connected to the tubing system and then the tip was inserted under the control of a micromanipulator and viewed with an operating microscope. After complete insertion of the tip, cyanoacrylate glue was applied again followed by the application of a thin layer of two part silicone adhesive (KWIK-Cast silicone elastomer sealant, WPI, Sarasota, USA) onto the dry cyanoacrylate glue layer. Perfusion of the probe was started immediately after probe placement. Substances were applied together to the RWM through a glass pipette mounted on a micromanipulator: Dexamethasone-21-dihydrogen-phosphate disodium salt (Fortecortin®Inject, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany, 8 mg/ml) and sodium fluorescein (Sigma-Aldrich, Taufkirchen, Germany, 10 mg/ml). The application commenced with a bolus application of 5 μl/min for one minute in order to fill the round window niche with fluid, continued by a slower rate (0.05 μl/min) to sustain the drug level in the round window niche up to approximately 5 h.

2.6. Quantification of dexamethasone-21-dihydrogen-phosphate using HPLC analysis

For the chromatographic separation and quantification of dexamethasone-21-dihydrogen-phosphate (DexP) an Agilent 1100 Series HPLC system (Agilent, Waldbronn, Germany) was used consisting of Solvent Degasser (G 1379 A), binary capillary pump (G 1389 A), autosampler thermostat (G 1330 A), autosampler MicroALS (G 1389 A), a column oven (G 1316 A) and DAD (G 1315 B). The chromatographic system consisted of a GROM-SIL 120 ODS-3CP, 5 lm, column (150 × 2.0 mm id, GROM Analytik, Herrenberg, Germany) and a solvent gradient of 25 mM potassium dihydrogen phosphate and acetonitrile was used. The column was operated at 20°C. The flow rate was set to 300 μl/min using the gradient as shown in Table 1. UV detection wavelengths were 241 and 254 nm. For data processing, HP Chemstation Rev. A.09.03 was used.

Table 1.

Gradient used for HPLC analysis of dexamethasone phosphate

| Time (min) | 25 mM KH2PO4 (%) | Acetonitrile (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | 0 |

| 1.5 | 80 | 20 |

| 7 | 10 | 90 |

| 11 | 10 | 90 |

| 12 | 80 | 20 |

| 18 | 80 | 20 |

We excluded data from five HPLC measurements due to technical difficulties with the HPLC system. Analysis in these experiments could not be repeated due to the limited sample volume available from the microdialysis procedure.

2.7. Computer simulations

Pharmacokinetics of the in vitro and the in vivo microdialysis experiments and of the cochlear fluids were interpreted using a finite element computer model (Washington University Cochlear Fluids Simulator, version 1.6i, available to the public on http://oto.wustl.edu/cochlea/). A detailed description of the model is given elsewhere (Salt, 2002). For this study, the computer model was modified to include the simulation of sampling by microdialysis. The model utilized the specific parameters of the microdialysis experiment, e.g., geometric dimensions of the tubular reservoirs and the cochlear fluid space dimensions, the fractional recovery rate of the microdialysis probe and the probe location, perfusion rate, sampling intervals and the molecular weight of the substances applied. For the in vitro experiments the measured concentrations were compared to the concentrations that were calculated by the model. For the in vivo experiments relevant pharmacokinetic parameters, specifically the round window membrane permeability, were derived by the means of inverse parameter identification through multiple forward simulations. Parameters were varied to minimize the sums of squares of differences between the calculated and the experimental data (Plontke et al., 2002).

3. Results

3.1. Recovery of sodium fluorescein from the tube reservoirs

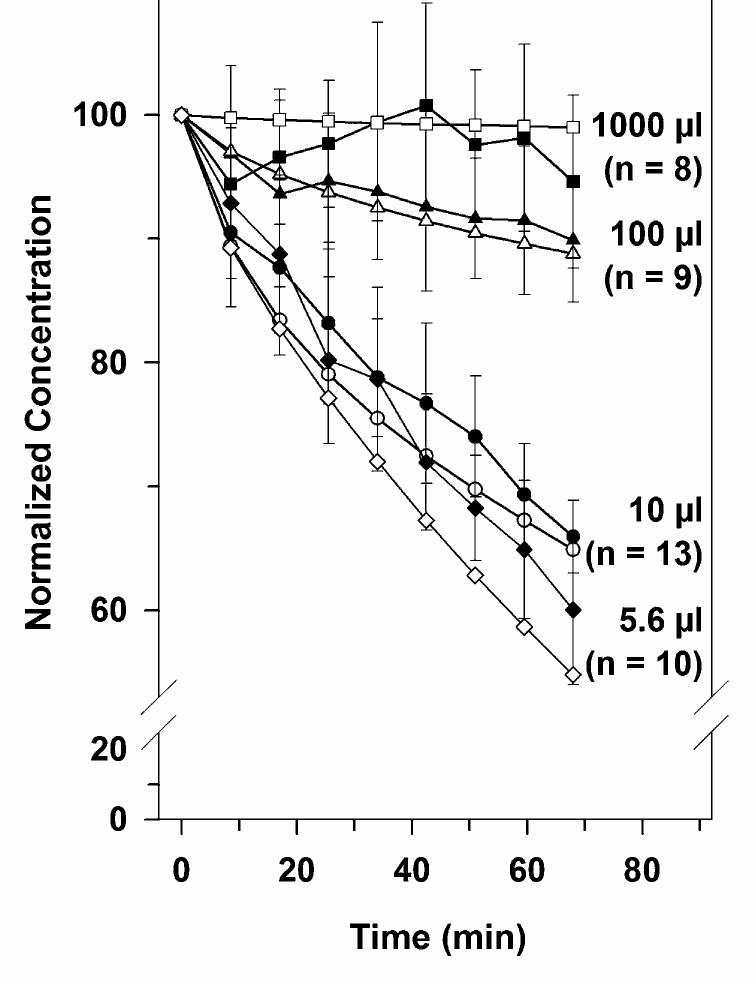

The retrieval of fluorescein by microdialysis in 1 ml reservoirs remained near constant during the entire experiment, while the concentration of fluorescein in samples retrieved from the smaller reservoirs gradually declined with time, as shown in Fig. 1. A regression analysis of the mean concentration data time courses showed significant slopes for the 5.6 μl (slope: 0.57%/min, p < 0.001), 10 μl (slope: -0.46%/min, p < 0.001) - and 100 μl (slope: 0.12%/min, p < 0.001) reservoirs, but not for 1000 μl reservoir (slope: -0.011%/min, p = 0.78). These results indicate that microdialysis allowed substances to be recovered from large volumes without significantly influencing the total reservoir concentrations, whereas in smaller compartment volumes the concentration of substances was reduced during the experiment.

Fig. 1.

Solid symbols: dependence of dialysis sample concentration on compartment volume in vitro. Compartment volumes were 1000 μl (squares), 100 μl (triangles), 10 μl (circles) and 5.6 μl (diamonds). For the large compartment volume, dialysis concentrations remained approximately constant with time, but sample concentrations decreased progressively with time for smaller compartments, with greater decreases for smaller compartments. Open symbols: simulation of the experiments using the Washington University Cochlear Fluid Simulator (http://oto.wus-tl.edu/cochlea) showing predicted decreases of comparable magnitude according to compartment volume.

To confirm that the reduction in the fluorescein concentrations measured in 100, 10 and 5.6 μl reservoirs was due to the retrieval of the dye by the microdialysis mechanism and not caused by a change in fractional recovery rate, the recovery rate was determined in 1 ml volumes before and at the end of a set of experiments which included 100, 10 and 5.6 μl reservoirs, respectively. These experiments showed that during the experiment the recovery rate and therefore the properties of the individual probe remained constant (data not shown).

Furthermore, to be sure that the decline in concentration was an actual decline in the concentration caused by microdialysis and not a function of dissociation of the dye from the probe surface, we measured the wash out kinetic of the dye from the probe at the end of the experiment. The probe was transferred to a 1-ml reservoir containing perfusion fluid (zero fluorescein concentration) and perfusion was started again. Within 1-2 samples, a sharp drop in the dye concentration was observed, indicating a rapid washout kinetic of the system.

3.2. In vivo experiments

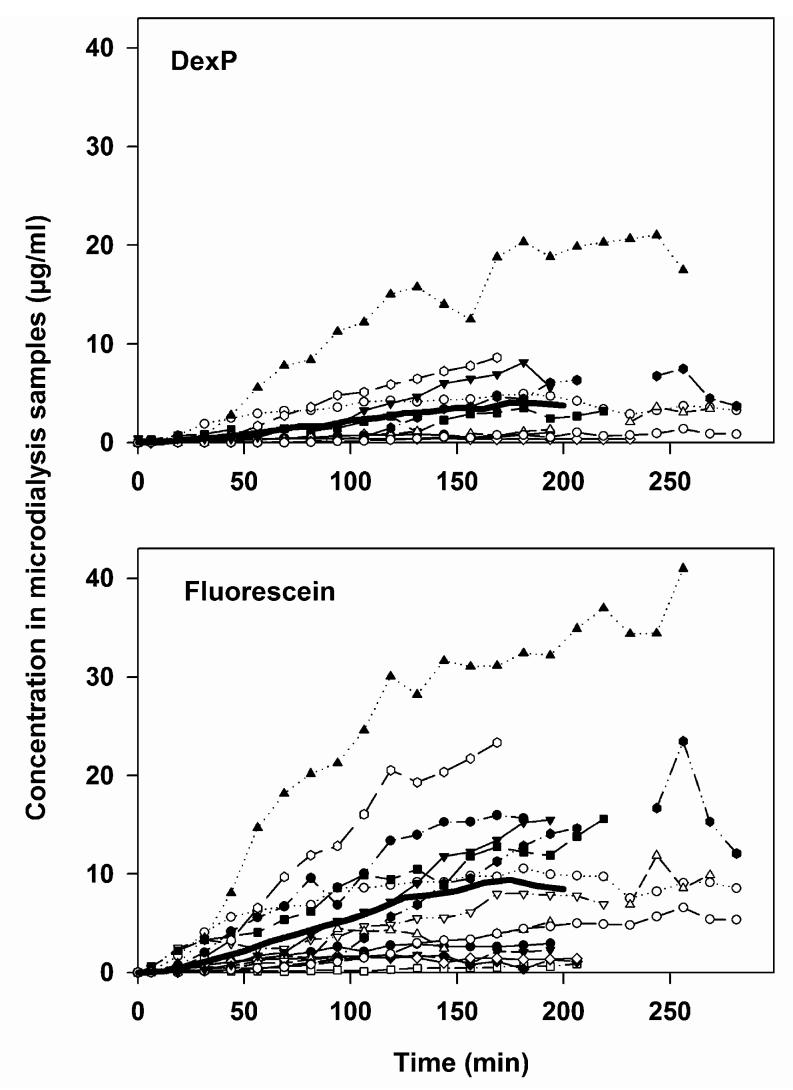

The concentration measured in microdialysis samples after continuous application of a solution containing both DexP (8 mg/ml) and sodium fluorescein (10 mg/ml) was higher for fluorescein than for DexP as shown in Fig. 2. The ratio between the averaged fluorescein and DexP concentrations measured in microdialysis samples was almost constant over time (2.3±0.7).

Fig. 2.

Measured concentration time courses of dexamethasone phosphate (DexP, upper panel, n = 10) and fluorescein (lower panel, n = 15) in microdialysis samples from the basal part of scala tympani after continuous application of a solution of the two drugs to the RWM of guinea pigs in vivo. Full line: mean. Note that the applied concentration of DexP was less (8 mg/ml) than that of fluorescein (10 mg/ml).

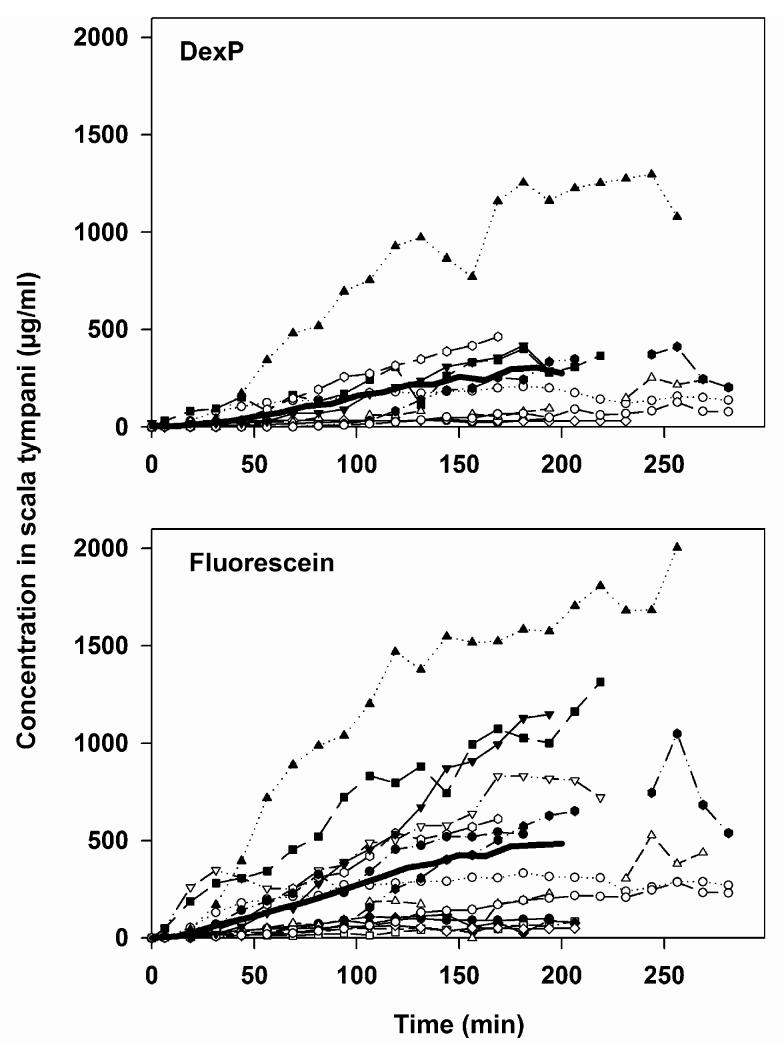

Conventionally, the estimated concentration at the sample location is obtained by dividing the measured sample concentration by the fractional recovery rate of the probe for each individual experiment, as shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Conventional way of presenting substance concentrations in microdialysis experiments based on the measurements shown in Fig. 2 and after correction for the recovery rate of the microdialysis probe. The data are not corrected, however, for additional clearance due to substance removal through the dialysis itself.

The recovery rates for fluorescein ranged from 0.96% to 3.82% (mean: 2.25%, SD: 0.90). The recovery rates for DexP ranged from 0.88% to 2.42% (mean: 1.63%; SD: 0.46).

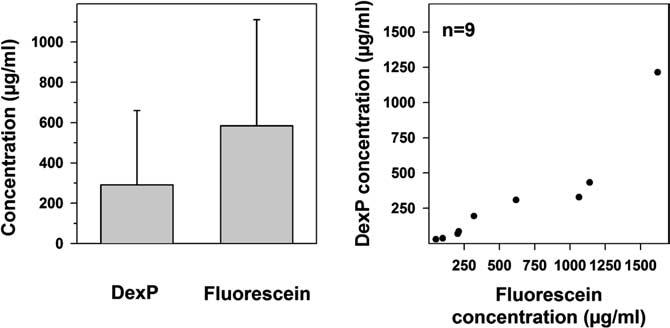

A comparison of the “terminal” concentrations for the two substances was performed by averaging the concentration measured at the time points 187.5, 200 and 212.5 min (Fig. 4). Values at these time points for both DexP and fluorescein were available in nine experiments. In these experiments, the mean terminal concentration for fluorescein was 585.5 ± 526.6 μg/ml, and that for DexP was 291.5 ± 369.3 μg/ml. After correcting for differences in the concentration applied to the RWM, the concentrations reached in the basal turn of scala tympani after approximately 200 min of drug application differed by a factor 1.6 between the two substances.

Fig. 4.

Comparison of substance concentrations of dexamethasone phosphate (DexP) and fluorescein in the basal turn of scala tympani. The average concentrations of DexP and fluorescein at the sampling time points of 187.5, 200 and 212.5 min are plotted only for those experiments where data for both of the two substances are available (n = 9). Note, that the applied concentration of DexP was less (8 mg/ml) than that of fluorescein (10 mg/ml). The right panel shows the correlation between DexP and fluorescein concentrations in individual animals.

Considerable variation in the amplitudes of the concentration time-courses were found between animals. For all experiments, the average minimum and maximum “terminal” concentrations were 48.4 and 1621.2 μg/ml for fluorescein and 29.6 and 1214.4 μg/ml for DexP, respectively. Thus, the measured maximum and minimum values varied by a factor of 34 for fluorescein and by at least 41 for DexP.

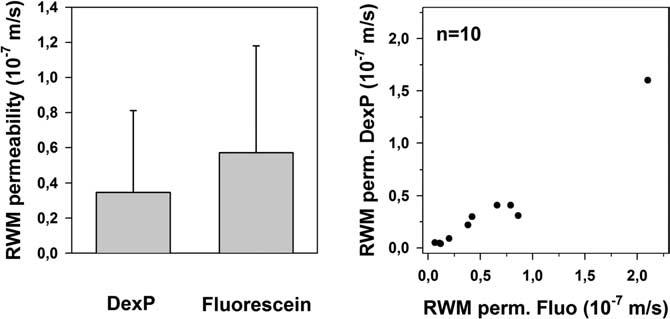

Round window membrane permeability was estimated using the finite element computer model as described in the methods section. This calculation considered all experimental details, including distance of the probe to the round window membrane and individual fractional recovery of the probe. The calculated average RWM permeability for fluorescein was 0.57 ± 0.61 × 10-7 m/s (minimum: 0.06; maximum: 2.10), and for DexP 0.35 ± 0.46 × 10-7 m/s (minimum: 0.04; maximum: 1.60) (see Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Comparison of RWM permeabilities (RWM perm.) for dexamethasone phosphate (DexP) and fluorescein, derived from simulations. The left panel shows the averaged RWM permeability for the two substances and the right panel shows the correlation between RWM permeabilities for DexP and fluorescein in individual animals.

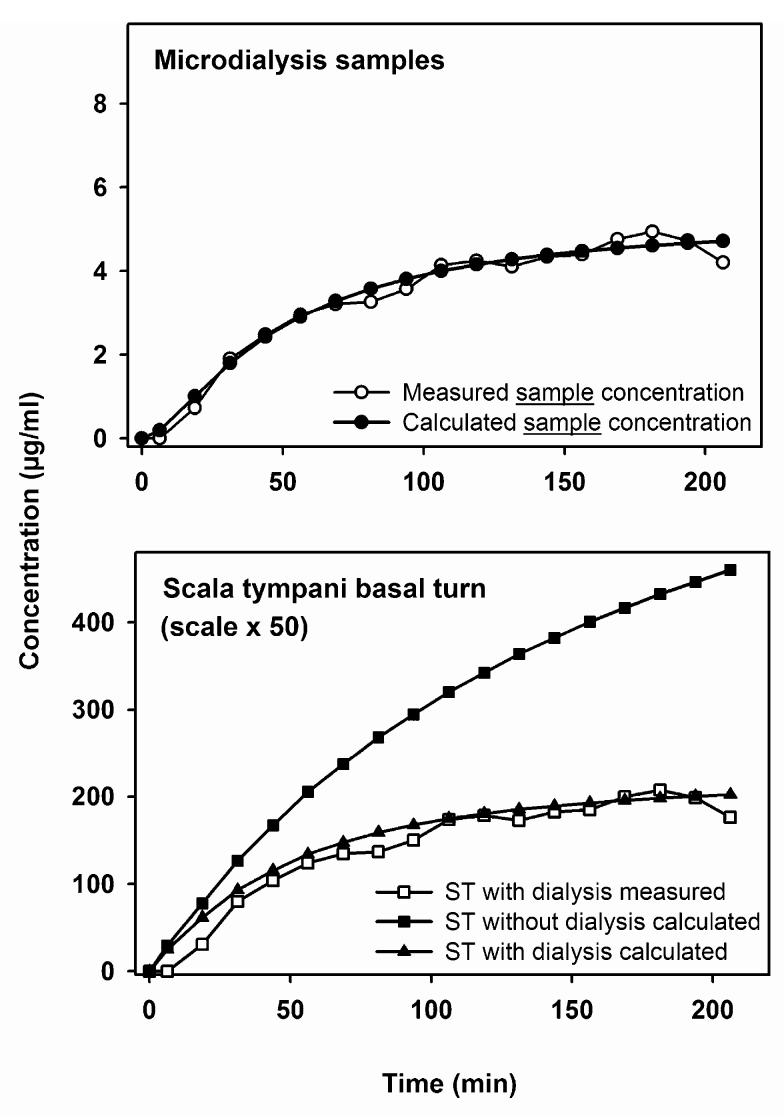

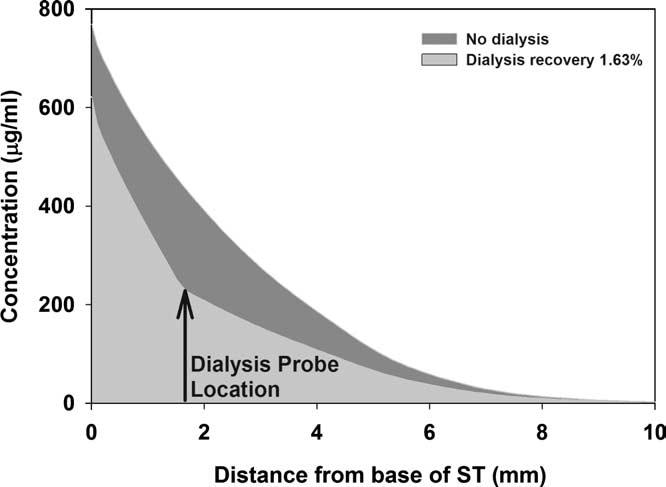

After determination of the round window permeability through reverse parameter identification using multiple forward simulations, the expected concentration time course at the sampling location was calculated in the presence and in the absence of microdialysis. An example is shown in Fig. 6. The upper panel shows that the dialysis samples predicted by the model compare well with the experimental data. In the lower panel, the scala concentrations giving rise to the samples are calculated. The scala concentration calculated in the presence of dialysis again compares well with the concentration predicted from the measured data when considering the recovery rate. The third curve, however, shows the model calculation for exactly the same parameters except that the dialysis was turned off. The scala concentration in the absence of dialysis appears much higher than that when dialysis is present, demonstrating that microdialysis contributes a significant additional clearance of substance from the system. Thus, the concentration time course of drug in the cochlea would be higher if dialysis were not performed, than it is in the presence of dialysis. This is further demonstrated in Fig. 7, which shows the calculated longitudinal distribution of substance along the cochlea in the presence and absence of dialysis. It can be seen that the dialysis probe acts as a “sink”, removing a significant proportion of solute from the perilymph and thereby significantly disturbing the perilymph kinetics that would otherwise occur.

Fig. 6.

Computer assisted interpretation of in vivo microdialysis experiments. Upper panel: time course of dialysis samples calculated by the model (filled circles), using model parameters (such as RWM permeability) to best fit the model results to the measured concentration time course (open circles). Lower panel: calculated concentration time courses in ST based on: (1) correction for the recovery rate of the microdialysis probe (open squares), (2) the concentration at the dialysis location determined by the computer simulation (solid triangles), and (3) the concentration at the dialysis location determined by the computer simulation without the additional clearance due to the removal of substance from the cochlea by microdialysis (solid squares). ST, scala tympani.

Fig. 7.

Calculated influence of dialysis on perilymph concentration of dexamethasone phosphate with distance along scala tympani. The kinetics in perilymph is markedly influenced by the loss of drug into the dialysis probe.

4. Discussion

There is limited information concerning drug levels inside fluid spaces of the inner ear after topical administration to the round window membrane of both human patients and laboratory animals. Since there is no drug approved yet for clinical application to the RWM preclinical data are necessary including pharmacokinetic data. Microdialysis has been proposed as an effective way of assessing cochlear fluid composition of laboratory animals. It has the advantage of repeated measurements allowing drug time course determination, prevention of artifacts from perilymph volume loss through leaks and less disturbance of perilymph due to the low amounts of drug recovery.

The in vitro experiments in this study with tubular models of different size showed that despite the low amounts of drug recovery, microdialysis causes a decrease in measured substance concentration which is relevant for small fluid compartments comparable to the dimensions of the cochlear scalae. The loss of drug from the fluid space into the dialysis probe therefore needs to be considered when interpreting pharmacokinetic studies using microdialysis in vivo. Since the dialysis represents a form of clearance of drug from the scala, it has to be considered whether the clearance by dialysis is significant. This depends to some extent on the cochlear pharmacokinetics, as for substances that are cleared rapidly by the cochlea, the influence of dialysis is less significant than that for a substance which is cleared very slowly by the cochlea. Other groups have presented clearance values (elimination kinetics rate constants) derived from measurements of the decline in perilymph concentration using microdialysis after RWM application is terminated (Hibi et al., 2001; Hunter et al., 2003). These clearance rates are likely to greatly exaggerate the physiologic clearance rate and should not be regarded as accurately representing perilymph kinetics in the absence of microdialysis. Thus, for dialysis experiments, in addition to drug clearance to the systemic blood flow, binding or metabolism, the loss of drug from the perilymph due to the dialysis procedure itself needs to be considered. One useful approach in the consideration of these sampling artifacts is by estimating the actual concentration using the above mentioned computer model or by a similar mathematical strategy. However, it is not possible to accurately assess the physiologic clearance rate through such analysis in the presence of a non-physiologic clearance caused by dialysis. This limitation does not invalidate all uses of dialysis data. For example, the RWM permeability properties established in the present study are thought to be an accurate representation, since the analysis takes into account the concentration gradient and should be unaffected by the dialysis. However, quantification of the perilymph kinetics of a drug, which depends critically on the rate of clearance of the drug from the cochlea, cannot be reliably assessed with the present microdialysis method. Nevertheless, it is apparent that the values derived by microdialysis are still much closer to the expected actual concentrations in perilymph than those obtained through “conventional” volume sampling techniques through the RWM or through the cochlear wall in the basal turn. There, it has been estimated that 10 μl fluid samples contain as little as 15% perilymph with the balance of the fluid volume being cerebrospinal fluid which is drawn into ST through the cochlear aqueduct (Salt et al., 2003).

When compared to the two other published studies measuring dexamethasone concentration in the guinea pig cochlea after RWM application, our values are much higher: 291.5 ± 369.3 μg/ml versus 1.6 ± 1.0 μg/ml in Parnes et al., 1999 and 13.2 ± 10.6 μg/ml in Chandrasekhar et al., 2000 study, respectively. Several factors have to be considered when comparing the available results for drug concentrations in the three studies: (1) the applied concentration, (2) the application time, and (3) the sampling procedure including sampling volume and location of sampling. For one study (Parnes et al., 1999) it was shown that the published steroid levels grossly underestimate the actual levels in perilymph before sampling due to artifacts associated with repeated large volume samples (4 × 10 μl perilymph aspiration near the cochlear aqueduct with subsequent dilution by cerebrospinal fluid) (Salt et al., 2003; Salt and Plontke, 2005). A similar explanation probably accounts for differences with the study by Chandrasekhar et al. (2000) although quantitative interpretation is not possible due to the incomplete description of methods in that publication.

Another factor contributing to the differences is the application time. The continuous application paradigm used in this study is likely to cause higher intracochlear drug levels than the single shot application which was used by the other groups. In our experiments, the estimated perilymph concentration giving rise to the average concentration in the 25-37.5 min microdialysis sample was 28.4 ± 34.5 μg/ml. After considering all of the above factors in the application and sampling strategies, this value appears in good correspondence with the measurements in the two other studies.

In addition to the quantification of substance concentrations in perilymph, a major conclusion from our in vivo experiments is the considerable range in concentration observed for both, fluorescein and DexP concentration in scala tympani. A high variation in drug concentrations measured in perilymph samples after RWM application has also been described by other authors: Parnes et al. (1999) found maximum concentrations of 1.6 ± 1.0 μg/ml for dexamethasone, 72.4 ± 23.3 μg/ml for hydrocortisone, and 50.4 ± 19.1 μg/ml for methylprednisolone in scala tympani perilymph samples after round window delivery. Chandrasekhar et al. (2000) measured 13.2 ± 10.6 μg/ml of dexamethasone. A peak concentration of 952.3 ± 382.7 μg/ml prednisolone was recorded by Bachmann et al. (2001). Hoffer et al. (2001) reported a peak concentration of 900 μg/ml (gentamicin) with a standard deviation of 1994 μg/ml and a range of 633-6950 μg/ml after intratympanic injection and sample volume aspiration. Using microdialysis for measuring drug perilymph concentrations Hibi et al. (2001) reported gentamicin peak concentrations of 2900 ± 1200 and 3000 ± 900 μg/ml depending on the protocol for application to the round window membrane.

We think that these variations in perilymph concentrations are mainly based on a significant variability in RWM permeability. Therefore, the quantification of RWM permeability is extremely important as this factor appears to dramatically influence the perilymph levels of drug achieved. A high inter-individual heterogeneity of the drug concentration within the inner ear due to variability in RWM permeability with subsequent variability of the therapeutic effects was specifically suggested by Chelikh et al. (2003) who applied inulin or mannitol topically to the RWM. The radioactivity in cochlear perilymph measured at day four after application of 3H-mannitol and 3H-inulin were 156 ± 80.3 and 16 ± 10.6 cpm/μl, respectively.

Studies using methods other than fluid aspiration (i.e., “volume sampling”), and thereby avoiding or at least minimizing sampling artifacts also suggested a considerable inter-animal variation in RWM permeability. Using ion selective electrodes, Salt and Ma (2001) and Salt et al. (2003) measured TMPA levels in scala tympani after round window application before and during sample aspiration. Measured TMPA levels and calculated round window permeabilities showed a rather larger degree of variation and it was hypothesized that RWM permeability may also be influenced by manipulations of the middle ear and/or intracochlear pressure (Salt and Ma, 2001; Salt et al., 2003). Understanding the origins of RWM permeability variation and of treatments that influence permeability could be of potential interest for clinicians.

In our experiments, variation in the concentration reached after continuous application do not appear to be caused by the analytic methods employed. Fluorescein and DexP were analyzed by different methods and the ratio between fluorescein and DexP concentration measured in microdialysis samples were rather constant throughout the experiments. Since sampling substances from cochlear fluids using microdialysis is a continuous sampling technique, variations are also unlikely to be a problem of inter-sample variation.

Another aspect, however, is the conversion of dexamethasone-21-dihydrogen-phosphate as the commercially available, stable, applicable form into the active moiety dexamethasone by phosphatases (Kroin et al., 2000). Although we think that due to the short distance between the application site (RWM) and the microdialysis probe location, the amount of conversion before detection by the probe is low, we have not quantified this in our study. However, separately quantifying the prodrug and the active drug might be of interest in further studies, especially when investigating dose-effect relationships.

The conversion of the prodrug into the biologically active drug, but also binding to cochlear glucocorticoid receptors and the method of microdialysis contribute to removal of dexamethasone phosphate from the cochlear fluids. They are pooled together in what we call clearance in general and cannot easily be separated from each other. Since clearance was considered in the computations, the calculated RWM permeability values should not be affected. In addition to the RWM permeability, however, these biological processes and the microdialysis method itself may all contribute individually to the large variation seen in the scala tympani perilymph concentration.

Despite the advantages described above, microdialysis does not appear to be a suitable method for measuring concentrations at locations distant from the basal turn of the cochlea. The probe used in our study was the smallest commercially available to this date, with a probe tip of 0.24 × 1 mm. It is currently not possible to insert a probe tip of this size into higher turns of the cochlea without damaging the boundaries between the fluid compartments.

In summary, microdialysis is a suitable method for: (i) quantification of substance concentrations in the basal part of scala tympani in animals with a cochlea the size of the guinea pig or larger, (ii) for quantification of round window membrane permeability and (iii) for the reduction of sampling artifacts due to the low amount of drug recovery. The limitations of the method in pharmacokinetic studies in the inner ear are: (i) the greater technical difficulty of the method, (ii) the restricted locations available for measurement (i.e., basal turn), and (iii) the inability to quantify clearance values accurately for the inner ear.

Acknowledgements

We thank Klaus Vollmer for his assistance as a tool mechanic in preparing the microdialysis probe holders. We thank Ruth Gill and Shane Hale for technical assistance in the computer simulations and Mrs. Antje Frickenschmidt, Ursula Delabar, PhD, and Mrs. Maisaa Sakr for technical assistance with HPLC analysis. This research was supported by grants from the University of Tübingen fortune-program Project No. 1001-0-0 to SP and by NIH/NIDCD Grant RO1 DC01368 to ANS.

Footnotes

- DexP

- dexamethasone-21-dihydrogen phosphate

- HPLC

- high performance liquid chromatography

- RWM

- round window membrane

- ST

- scala tympani

- TMPA

- trimethylphenylammonium

References

- Bachmann G, Su J, Zumegen C, Wittekindt C, Michel O. Permeabilität der runden Fenstermembran für Prednisolon-21-Hydrogensuccinat. HNO. 2001;49:538–542. doi: 10.1007/s001060170078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarani A, Capobianco S, Soi D, Giuliano DA, Alpini D. Intratympanic dexamethasone treatment for control of subjective idiopathic tinnitus: our clinical experience. Int. Tinnitus J. 2002;8:111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar SS. Intratympanic dexamethasone for sudden sensorineural hearing loss: clinical and laboratory evaluation. Otol. Neurotol. 2001;22:18–23. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandrasekhar SS, Rubinstein RY, Kwartler JA, Gatz M, Connelly PE, Huang E, Baredes S. Dexamethasone pharmaco-kinetics in the inner ear: comparison of route of administration and use of facilitating agents. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2000;122:521–528. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.102578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chelikh L, Teixeira M, Martin C, Sterkers O, Ferrary E, Couloigner V. High variability of perilymphatic entry of neutral molecules through the round window. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:199–202. doi: 10.1080/00016480310001042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Duan M, Lee H, Ruan R, Ulfendahl M. Pharmacokinetics of caroverine in the inner ear and its effects on cochlear function after systemic and local administrations in Guinea pigs. Audiol. Neurootol. 2003a;8:49–56. doi: 10.1159/000067893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Ulfendahl M, Ruan R, Tan L, Duan M. Acute treatment of noise trauma with local caroverine application in the guinea pig. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003b;123:905–909. doi: 10.1080/00016480310000638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles RR, Thompson AC, O’Donoghue GM. Intra-tympanic injections in the treatment of tinnitus. Clin. Otolaryngol. 1992;17:240–242. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1992.tb01835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange EC, de Boer AG, Breimer DD. Methodological issues in microdialysis sampling for pharmacokinetic studies. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2000;45:125–148. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(00)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmquist WF, Sawchuk RJ. Application of microdialysis in pharmacokinetic studies. Pharm. Res. 1997;14:267–288. doi: 10.1023/a:1012081501464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gianoli GJ, Li JC. Transtympanic steroids for treatment of sudden hearing loss. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:142–146. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.117162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouveris H, Selivanova O, Mann W. Intratympanic dexamethasone with hyaluronic acid in the treatment of idiopathic sudden sensorineural hearing loss after failure of intravenous steroid and vasoactive therapy. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:131–134. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0772-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goycoolea MV. Clinical aspects of round window membrane permeability under normal and pathological conditions. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:437–447. doi: 10.1080/000164801300366552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hibi T, Suzuki T, Nakashima T. Perilymphatic concentration of gentamicin administered intratympanically in guinea pigs. Acta Otolaryngol. 2001;121:336–341. doi: 10.1080/000164801300102699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hight NG, McFadden SL, Henderson D, Burkard RF, Nicotera T. Noise-induced hearing loss in chinchillas pre-treated with glutathione monoethylester and R-PIA. Hear. Res. 2003;179:21–32. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho HG, Lin HC, Shu MT, Yang CC, Tsai HT. Effectiveness of intratympanic dexamethasone injection in sudden-deafness patients as salvage treatment. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:1184–1189. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200407000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffer ME, Allen K, Kopke RD, Weisskopf P, Gottshall K, Wester D. Transtympanic versus sustained-release administration of gentamicin: kinetics, morphology, and function. Laryngoscope. 2001;111:1343–1357. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200108000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoya N, Ogawa K, Inoue Y, Takiguchi Y, Kanzaki J. The glutamate receptor agonist, AMPA, induces acetylcholine release in guinea pig cochlea; a microdialysis study. Neurosci. Lett. 2001;311:206–208. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(01)02165-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter BA, Lee S, Odland RM, Juhn SK. Estimation of perilymph concentration of agents applied to the round window membrane by microdialysis. Acta Otolaryngol. 2003;123:453–458. doi: 10.1080/00016480310000467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh A, Sakata E. Treatment of vestibular disorders. Acta Otolaryngol. Suppl. 1991;481:617–623. doi: 10.3109/00016489109131486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jager W, Goiny M, Herrera-Marschitz M, Brundin L, Fransson A, Canlon B. Noise-induced aspartate and glutamate efflux in the guinea pig cochlea and hearing loss. Exp. Brain Res. 2000;134:426–434. doi: 10.1007/s002210000470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keithley EM, Ma CL, Ryan AF, Louis JC, Magal E. GDNF protects the cochlea against noise damage. Neuroreport. 1998;9:2183–2187. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199807130-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroin JS, Schaefer RB, Penn RD. Chronic intrathecal administration of dexamethasone sodium phosphate: pharmacokinetics and neurotoxicity in an animal model. Neurosurgery. 2000;46:178–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopke RD, Hoffer ME, Wester D, O’Leary MJ, Jackson RL. Targeted topical steroid therapy in sudden sensorineural hearing loss. Otol. Neurotol. 2001;22:475–479. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200107000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautermann J, Sudhoff H, Junker R. Transtympanic corticoid therapy for acute profound hearing loss. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2005;262:587–591. doi: 10.1007/s00405-004-0876-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre PP, Staecker H. Steroid perfusion of the inner ear for sudden sensorineural hearing loss after failure of conventional therapy: a pilot study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2002;122:698–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Frenz DA, Brahmblatt S, Feghali JG, Ruben RJ, Berggren D, Arezzo J, Van De Water TR. Round window membrane delivery of l-methionine provides protection from cisplatin ototoxicity without compromising chemotherapeutic efficacy. Neurotoxicology. 2001;22:163–176. doi: 10.1016/s0161-813x(00)00010-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda K, Ueda Y, Haruta A, Tono T, Komune S. High potassium-induced glutamate release in the cochlea: in vivo microdialysis study combined with on-line enzyme fluorometric detection of glutamate. Brain Res. 1998;794:343–346. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(98)00330-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parnes LS, Sun AH, Freeman DJ. Corticosteroid pharmaco-kinetics in the inner ear fluids: an animal study followed by clinical application. Laryngoscope. 1999;109:1–17. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199907001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plock N, Kloft C. Microdialysis-theoretical background and recent implementation in applied life-sciences. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2005;25:1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2005.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plontke SK, Wood AW, Salt AN. Analysis of gentamicin kinetics in fluids of the inner ear with round window administration. Otol. Neurotol. 2002;23:967–974. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200211000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plontke S, Lowenheim H, Preyer S, Leins P, Dietz K, Koitschev A, Zimmermann R, Zenner HP. Outcomes research analysis of continuous intratympanic glucocorticoid delivery in patients with acute severe to profound hearing loss: basis for planning randomized controlled trials. Acta Otolaryngol. 2005;125:830–839. doi: 10.1080/00016480510037898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata E, Ito Y, Itoh A. Clinical experiences of steroid targeting therapy to inner ear for control of tinnitus. Int. Tinnitus J. 1997;3:117–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN. Simulation of methods for drug delivery to the cochlear fluids. Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;59:140–148. doi: 10.1159/000059251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN, Ma Y. Quantification of solute entry into cochlear perilymph through the round window membrane. Hear. Res. 2001;154:88–97. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(01)00223-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN, Plontke SK. Local inner ear drug delivery and pharmacokinetics. Drug Discov. Today. 2005;10:1299–1306. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03574-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salt AN, Kellner C, Hale S. Contamination of perilymph samples from the basal cochlear fluid with cerebrospinal fluid. Hear. Res. 2003;182:23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(03)00137-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheibe F, Haupt H, Bergmann K. On sources of error in the biochemical study of perilymph (guinea pig) Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 1984;240:43–48. doi: 10.1007/BF00464343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sennaroglu L, Sennaroglu G, Gursel B, Dini FM. Intratympanic dexamethasone, intratympanic gentamicin, and endolymphatic sac surgery for intractable vertigo in Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:537–543. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2001.119485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shea JJ, Jr., Ge X. Dexamethasone perfusion of the labyrinth plus intravenous dexamethasone for Meniere’s disease. Otolaryngol. Clin. North Am. 1996;29:353–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shulman A, Goldstein B. Intratympanic drug therapy with steroids for tinnitus control: a preliminary report. Int. Tinnitus J. 2000;6:10–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein H, Choo D, Rosenberg SI, Kuhn J, Seidman M, Stein I. Intratympanic steroid treatment of inner ear disease and tinnitus (preliminary report) Ear Nose Throat J. 1996;75 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein H, Isaacson JE, Olds MJ, Rowan PT, Rosenberg S. Dexamethasone inner ear perfusion for the treatment of Meniere’s disease: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. Am. J. Otol. 1998;19:196–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trune DR. In: Ion homeostasis and inner ear disease. In: Medical Otology and Neurotology. Hamid M, Sismanis A, editors. Thieme Publishing; 2006. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Ungerstedt U. Microdialysis-principles and applications for studies in animals and man. J. Int. Med. 1991;230:365–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00459.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]