Abstract

Corticosteroids are the most effective anti-inflammatory therapy for many chronic inflammatory diseases, such as asthma but are relatively ineffective in other diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Chronic inflammation is characterised by the increased expression of multiple inflammatory genes that are regulated by proinflammatory transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-kappaB and activator protein-1, that bind to and activate coactivator molecules, which then acetylate core histones to switch on gene transcription. Corticosteroids suppress the multiple inflammatory genes that are activated in chronic inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, mainly by reversing histone acetylation of activated inflammatory genes through binding of liganded glucocorticoid receptors (GR) to coactivators and recruitment of histone deacetylase-2 (HDAC2) to the activated transcription complex. At higher concentrations of corticosteroids GR homodimers also interact with DNA recognition sites to active transcription of anti-inflammatory genes and to inhibit transcription of several genes linked to corticosteroid side effects. In patients with COPD and severe asthma and in asthmatic patients who smoke HDAC2 is markedly reduced in activity and expression as a result of oxidative/nitrative stress so that inflammation becomes resistant to the anti-inflammatory actions of corticosteroids. Theophylline, by activating HDAC, may reverse this corticosteroid resistance. This research may lead to the development of novel anti-inflammatory approaches to manage severe inflammatory diseases.

Keywords: Steroid resistance, transcription factor, glucocorticosteroid, glucocorticoid receptor, nuclear factor-κB, histone acetyltransferase, histone deacetylase, theophylline

Introduction

Corticosteroids (also known as glucocorticosteroids, glucocorticoids or just steroids) are among the most widely used drugs in the world and are effective in many inflammatory and immune diseases. The most common use of corticosteroids is in the treatment of asthma, where inhaled corticosteroids have become first-line therapy and by far the most effective anti-inflammatory treatment. There have been important advances in understanding the molecular mechanisms whereby corticosteroids suppress inflammation so effectively in asthma and other inflammatory disease, based on recent developments in understanding the fundamental mechanisms of gene transcription and cell signalling in inflammation (Barnes & Adcock, 2003; Rhen & Cidlowski, 2005). This new understanding of these new molecular mechanisms also helps to explain how corticosteroids are able to switch off multiple inflammatory pathways, yet remain a safe treatment. It also provides insights into why corticosteroids fail to work in patients with inflammatory diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and cystic fibrosis (Barnes et al., 2004).

The Nobel Prize for Medicine and Physiology in 1950 was awarded to Kendall and Reichstein, who had independently isolated and synthesised cortisol and then adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and Philip Hench, a rheumatologist working at the Mayo Clinic, who had described the dramatic efficacy of ACTH in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Only 6 months after Hench's discovery, Boardley and colleagues at John Hopkins University showed that ACTH had dramatic benefits in patients with asthma (Boardley et al., 1949). Oral corticosteroids were subsequently shown to be as effective but their use was limited by systemic side effects that are well known today. The breakthrough that revolutionised asthma therapy was the introduction of inhaled corticosteroids that had topical activity in 1972 (Brown et al., 1972).

The predominant effect of corticosteroids is to switch off multiple inflammatory genes (encoding cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules, inflammatory enzymes, receptors and proteins) that have been activated during the chronic inflammatory process. In higher concentrations they have additional effects on the synthesis of anti-inflammatory proteins and postgenomic effects. This review discusses how corticosteroids so effectively switch off multiple inflammatory genes in steroid-sensitive inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, whereas fail to control inflammation in other inflammatory diseases, such as COPD.

Molecular mechanisms of chronic inflammation

Chronic inflammatory diseases, such as asthma, COPD rheumatoid arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, involve the infiltration and activation of many inflammatory and immune cells, which release multiple inflammatory mediators that interact and activate structural cells at the site of inflammation. The pattern of inflammation clearly differs between these diseases, with the involvement of many different cells and mediators (Barnes et al., 1998; Barnes, 2004b), but all are characterised by increased expression of multiple inflammatory proteins, some of which are common to all inflammatory diseases, whereas others are more specific to a particular disease. The increased expression of most of these inflammatory proteins is regulated at the level of gene transcription through the activation of proinflammatory transcription factors, such as nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) and activator protein-1 (AP-1). These proinflammatory transcription factors are activated in all inflammatory diseases and play a critical role in amplifying and perpetuating the inflammatory process. Thus, NF-κB is activated in the airways of asthmatic patients and COPD patients (Hart et al., 1998; Di Stefano et al., 2002) and is activated in the joints of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (Muller-Ladner et al., 2002) and the vessels of patients with atherosclerosis (Monaco & Paleolog, 2004). The molecular pathways involved in regulating inflammatory gene expression are now being delineated and it is now clear that chromatin remodelling plays a critical role in the transcriptional control of genes. Stimuli that switch on inflammatory genes do so by changing the chromatin structure of the gene, whereas corticosteroids reverse this process.

Chromatin remodelling and gene expression

Chromatin is composed of DNA and histones, which are basic proteins that provide the structural backbone of the chromosome. It has long been recognised that histones play a critical role in regulating the expression of genes and determines which genes are transcriptionally active and which ones are suppressed (silenced). The chromatin structure is highly organised as almost 2 m of DNA have to be packed into each cell nucleus. Chromatin is made up of nucleosomes which are particles consisting of 146 base pairs of DNA wound almost twice around an octomer of two molecules each of the core histone proteins H2A, H2B, H3 and H4. In the last decade it has been shown that expression and repression of genes is associated with remodelling of this chromatin structure by enzymatic modification of the core histone proteins, particularly through acetylation of lysine residues. Each core histone has a long N-terminal tail that is rich in lysine residues, which may become acetylated, thus changing the electrical charge of the core histone. In the resting cell DNA is wound tightly around core histones, excluding the binding of the enzyme RNA polymerase II, which activates gene transcription and the formation of messenger RNA. This conformation of the chromatin structure is described as closed and is associated with suppression of gene expression. Gene transcription only occurs when the chromatin structure is opened up, with unwinding of DNA so that RNA polymerase II and basal transcription complexes can now bind to DNA to initiate transcription.

Histone acetyltransferases and coactivators

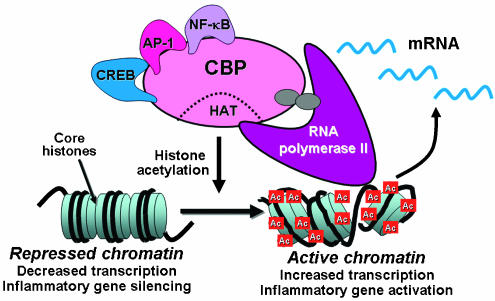

Switching on of inflammatory genes requires the engagement of coactivator molecules which interact with proinflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB, that are bound to specific recognition sequences in the promoter region of inflammatory genes. These large coactivator molecules, such as cyclic AMP response element binding (CREB) binding protein (CBP), p300 and p300-CBP associated factor (pCAF), thus act as the molecular switches that control gene transcription and all have intrinsic histone acetyltransferase (HAT) activity. This results in acetylation of core histones, thereby reducing their charge which allows the chromatin structure to transform from the resting closed conformation to an activated open form (Roth et al., 2001) (Figure 1). This results in unwinding of DNA, binding of TATA box binding protein (TBP), TBP-associated factors and RNA polymerase II, which then initiates gene transcription. This molecular mechanism is common to all genes, including those involved in differentiation, proliferation and activation of cells. This process is reversible and deacetylation of acetylated histones is associated with gene silencing. This is mediated by histone deacetylases (HDACs) which act as corepressors, together with other corepressor proteins which are subsequently recruited.

Figure 1.

Gene regulation by histone acetylation. Coactivator molecules such as CBP interact with transcription factors such as CREB, AP-1 and NF-κB, resulting in activation of their intrinsic HAT activity. This results in acetylation (Ac) of core histones, opening up the chromatin structure to allow binding on RNA polymerase II, which initiates gene transcription.

These fundamental gene regulatory mechanisms have now been applied to understand the regulation of inflammatory genes in diseases, such as asthma and COPD (Barnes, 2004a). In a human epithelial cell line activation of NF-κB, by exposing the cell to inflammatory signals such as IL-1β, tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) or endotoxin, results in acetylation of specific lysine residues on histone H4 (the other histones do not appear to be so markedly or rapidly acetylated) and this is correlated with increased expression of genes encoding inflammatory proteins, such as granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF) (Ito et al., 2000).

HDACs and corepressors

The acetylation of histone that is associated with increased expression of inflammatory genes is counteracted by the activity of HDACs, of which 11 that deacetylate histones are now identified in mammalian cells (de Ruijter et al., 2003; Thiagalingam et al., 2003). There is now evidence that the different HDACs target different patterns of acetylation and therefore regulate different types of gene (Peterson, 2002). HDACs act as corepressors in consort with other corepressor proteins, such as nuclear receptor corepressor (NCoR) and silencing mediator of retinoid and thyroid hormone receptors (SMRT), forming a corepressor complex that silences gene expression (Privalsky, 2004). In biopsies from patients with asthma there is an increase in HAT and a reduction in HDAC activity, thereby favouring increased inflammatory gene expression (Ito et al., 2002a). Understanding the molecular basis for inflammatory gene expression provides the background for understanding how corticosteroids are so effective in suppressing complex inflammatory diseases that involve the increased expression of multiple inflammatory proteins.

Glucocorticoid receptors

Corticosteroids diffuse readily across cell membranes and bind to glucocorticoid receptors (GR) in the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic GR are normally bound to proteins, known as molecular chaperones, such as heat shock protein-90 (hsp90) and FK-binding protein, that protect the receptor and prevent its nuclear localisation by covering the sites on the receptor that are needed for transport across the nuclear membrane into the nucleus (Wu et al., 2004). There is a single gene encoding human GR but several variants are now recognised, as a result of transcript alternative splicing, and alternative translation initiation (Rhen & Cidlowski, 2005). GRα binds corticosteroids, whereas GRβ is an alternatively spliced form that binds to DNA but cannot be activated by corticosteroids. GRβ has a very low level of expression compared to GRα (Pujols et al., 2002). The GRβ isoform has been implicated in steroid resistance in asthma (Leung et al., 1997), although whether GRβ can have any functional significance has been questioned in view of the very low levels of expression compared to GRα (Hecht et al., 1997).

GR may also be modified by phosphorylation and other modifications, which may alter the response to corticosteroids by affecting ligand binding, translocation to the nucleus, trans-activating efficacy, protein–protein interactions or recruitment of cofactors (Bodwell et al., 1998; Ismaili & Garabedian, 2004). For example, there are a number of serine/threonines in the N-terminal domain where GR may be phosphorylated by various kinases.

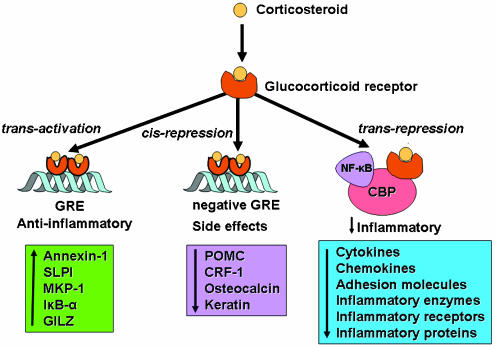

Once corticosteroids have bound to GR, changes in the receptor structure result in dissociation of molecular chaperone proteins, thereby exposing nuclear localisation signals on GR. This results in rapid transport of the activated GR–corticosteroid complex into the nucleus, where it binds to DNA at specific sequences in the promoter region of corticosteroid-responsive genes known as glucocorticoid response elements (GRE). Two GR molecules bind together as a homodimer and bind to GRE, leading to changes in gene transcription. Interaction of GR with GRE classically leads to an increase in gene transcription (trans-activation), but negative GRE sites have also been described where binding of GR leads to gene suppression (cis-repression) (Dostert & Heinzel, 2004) (Figure 2). There are few well-documented examples of negative GREs, but some are relevant to corticosteroid side effects, including genes that regulate the hypothalamic–pituitary axis (pro-opiomelanocortin and corticotrophin releasing factor), bone metabolism (osteocalcin) and skin structure (keratins).

Figure 2.

Corticosteroids may regulate gene expression in several ways. Corticosteroids enter the cell to bind to GR in the cytoplasm that translocate to the nucleus. GR homodimers bind to GRE in the promoter region of steroid-sensitive genes, which may encode anti-inflammatory proteins. Less commonly, GR homodimers interact with negative GREs to suppress genes, particularly those linked to side effects of corticosteroids. Nuclear GR also interact with coactivator molecules, such as CBP, which is activated by proinflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB, thus switching off the inflammatory genes that are activated by these transcription factors. Other abbreviations: SLPI: secretory leukoprotease inhibitor; MKP-1: mitogen-activated kinase phosphatase-1; IκB-α: inhibitor of NF-κB; GILZ: glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper protein; POMC: proopiomelanocortin; CRF: corticotrophin-releasing factor.

Corticosteroid-induced gene transcription

Corticosteroids produce their effect on responsive cells by activating GR to directly or indirectly regulate the transcription of target genes. The number of genes per cell directly regulated by corticosteroids is estimated to be between 10 and 100, but many genes are indirectly regulated through an interaction with other transcription factors and coactivators. GR homodimers bind to GRE sites in the promoter region of corticosteroid-responsive genes. Interaction of the activated GR dimer with GRE usually increases transcription. GR may increase transcription by interacting with coactivator molecules, such as CBP and pCAF, thus inducing histone acetylation and gene transcription. For example, relatively high concentrations of corticosteroids increase the secretion of the antiprotease secretory leukoprotease inhibitor (SLPI) from epithelial cells (Ito et al., 2000).

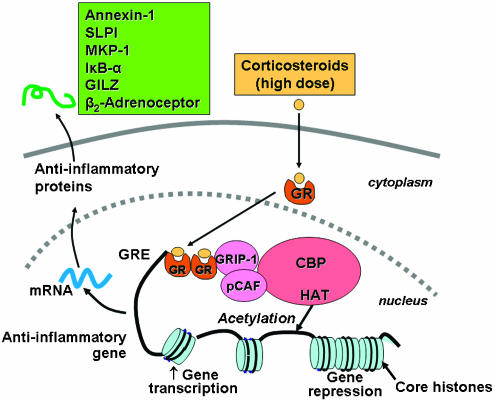

The activation of genes by corticosteroids is associated with a selective acetylation of lysine residues 5 and 16 on histone H4, resulting in increased gene transcription (Ito et al., 2000; Ito et al., 2001a) (Figure 3). Activated GR may bind to coactivator molecules, such as CBP or pCAF, as well as steroid-receptor coactivator-1 (SRC-1) and GR interacting protein-1 (GRIP-1), all of which possess HAT activity (Yao et al., 1996; Kurihara et al., 2002). GR preferentially associate with GRIP-1, which subsequently recruits pCAF (Li et al., 2003).

Figure 3.

Corticosteroids activation of anti-inflammatory gene expression. Corticosteroids bind to cytoplasmic GR, which translocate to the nucleus where they bind to GRE in the promoter region of steroid-sensitive genes and also directly or indirectly to coactivator molecules such as CBP, pCAF or GRIP-1, which have intrinsic HAT activity, causing acetylation of lysines on histone H4, which leads to activation of genes encoding anti-inflammatory proteins, such as SLPI, MKP-1, IκB-α and GILZ.

Anti-inflammatory gene activation

Several of the genes that are switched on by corticosteroids have anti-inflammatory effects, including annexin-1 (lipocortin-1), SLPI, interleukin-10 (IL-10) and the inhibitor of NF-κB (IκB-α). However, therapeutic doses of inhaled corticosteroids have not been shown to increase annexin-1 concentrations in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (Hall et al., 1999) and an increase in IκB-α has not been shown in most cell types, including epithelial cells (Heck et al., 1997; Newton et al., 1998a). Corticosteroids also switch on the synthesis of two proteins that affect inflammatory signal transduction pathways, glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper protein (GILZ), which inhibits both NF-κB and AP-1 (Mittelstadt & Ashwell, 2001) and MAP kinase phosphatase-1 (MKP-1), which inhibits p38 MAP kinase (Lasa et al., 2002). However, it seems unlikely that the widespread anti-inflammatory actions of corticosteroids could be entirely explained by increased transcription of small numbers of anti-inflammatory genes, particularly as high concentrations of corticosteroids are usually required for this effect, whereas in clinical practice corticosteroids are able to suppress inflammation at low concentrations.

‘Side effect' gene repression

Relatively little is known about the molecular mechanisms of corticosteroid side effects, such as osteoporosis, growth retardation in children, skin fragility and metabolic effects. These actions of corticosteroids are related to their endocrine effects. The systemic side effects of corticosteroids may be due to gene activation. Some insight into this has been provided by mutant GR, which do not dimerise and therefore cannot bind to GRE to switch on genes. In transgenic mice (dim−/−) expressing these mutant GR corticosteroids show no loss in their anti-inflammatory effects and are able to suppress NF-κB-activated genes in the normal way (Reichardt et al., 2001). Several of the genes associated with side effects, including the hypothalamo–pituitary axis, bone metabolism and skin structure, appear to be regulated by interaction of GR with negative GRE sites (Ismaili & Garabedian, 2004).

Corticosteroid repression of inflammatory genes

In controlling inflammation, the major effect of corticosteroids is to inhibit the synthesis of multiple inflammatory proteins through suppression of the genes that encode them. Although this was originally believed to be through interaction of GR with negative GRE sites, these have been demonstrated on only a few genes, which do not include genes encoding inflammatory proteins (Ismaili & Garabedian, 2004).

Interaction with transcription factors

Activated GRs may interact functionally with other activated transcription factors, without the necessity of binding to DNA (nongenomic effects). Most of the inflammatory genes that are activated in asthma do not have recognisable GRE sites in their promoter regions, yet are potently repressed by corticosteroids. There is persuasive evidence that corticosteroids inhibit the effects of proinflammatory transcription factors, such as AP-1 and NF-κB, that regulate the expression of genes that code for many inflammatory proteins, such as cytokines, inflammatory enzymes, adhesion molecules and inflammatory receptors (Barnes & Karin, 1997; Barnes & Adcock, 1998). Activated GR can interact directly with other activated transcription factors by protein–protein binding, but this may be a particular feature of cells in which these genes are artificially overexpressed, rather than a property of normal cells. Treatment of asthmatic patients with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids that suppress airway inflammation is not associated with any reduction in NF-κB binding to DNA, yet is able to switch off inflammatory genes, such as GM-CSF, that are regulated by NF-κB (Hart et al., 2000). This suggests that corticosteroids are more likely to be acting downstream of the binding of proinflammatory transcription factors to DNA and attention has now focused on their effects on chromatin structure and histone acetylation.

Effects on histone acetylation

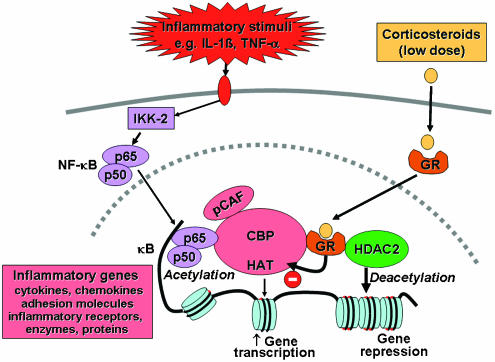

Repression of genes occurs through reversal of the histone acetylation that switches on inflammatory genes (Imhof & Wolffe, 1998). Activated GR may bind to CBP or other coactivators directly to inhibit their HAT activity (Ito et al., 2000), thus reversing the unwinding of DNA around core histones and thereby repressing inflammatory genes. More importantly, particularly at low concentrations that are likely to be relevant therapeutically in asthma treatment, activated GR recruits HDAC2 to the activated transcriptional complex, resulting in deacetylation of hyperacetylated histones, and thus a decrease in inflammatory gene transcription (Ito et al., 2000) (Figure 4). Using a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay we have demonstrated that corticosteroids recruit HDAC2 to the acetylated histone H4 associated with the GM-CSF promoter (Ito et al., 2000). Using interference RNA to selectively suppress HDAC2 in an epithelial cell line, we have shown that there is an increase in the expression of GM-CSF and reduced sensitivity to corticosteroids (Ito et al., 2006). By contrast, knockdown of HDAC1 and HDAC3 had no such effect on steroid responsiveness. An important issue that is not yet resolved is why corticosteroids selectively switch off inflammatory genes, while having no effect on genes that regulate proliferation, metabolism and cell survival. It is likely that GR only binds to coactivators that are activated by proinflammatory transcription factors, such as NF-κB and AP-1, although it is not yet understand how this specific recognition occurs.

Figure 4.

Corticosteroids suppression of activated inflammatory genes. Inflammatory genes are activated by inflammatory stimuli, such as IL-1β or TNF-α, resulting in activation of IKK2 (inhibitor of I-κB kinase-2), which activates the transcription factor NF-κB. A dimer of p50 and p65 NF-κB proteins translocates to the nucleus and binds to specific κB recognition sites and also to coactivators, such as CBP or pCAF, which have intrinsic HAT activity. This results in acetylation of core histone H4, resulting in increased expression of genes encoding multiple inflammatory proteins. GR after activation by corticosteroids translocate to the nucleus and bind to coactivators to inhibit HAT activity directly and recruiting HDAC2, which reverses histone acetylation leading in suppression of these activated inflammatory genes.

Other histone modifications

It has now become apparent that core histones may be modified not only by acetylation, but also by methylation, phosphorylation and ubiquitination and that these modifications may also regulate gene transcription (Berger, 2001; Peterson & Laniel, 2004). Methylation of histones, particularly histone H3, by histone methyltransferases, usually results in gene suppression (Bannister et al., 2002). The anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids are reduced by a methyltransferase inhibitor, 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine, suggesting that this may be an additional mechanism whereby corticosteroids suppress genes (Kagoshima et al., 2001). Indeed, there may be an interaction between acetylation, methylation and phosphorylation of histones, so that the sequence of chromatin modifications (the so called ‘histone code') may give specificity to expression of particular genes (Wang et al., 2004), including inflammatory genes (Wada et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2006).

GR acetylation

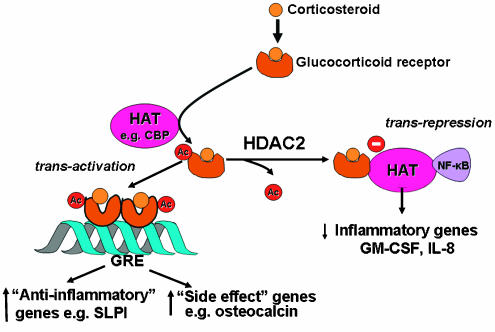

Nonhistone proteins are also acetylated by HATs and deacetylated by HDACs and this may be an important mechanism of regulating their function (Glozak et al., 2005). Several nuclear receptors, including the oestrogen and androgen receptors, may be acetylated and this affects binding of their hormones (Fu et al., 2004). We have recently demonstrated that GR is acetylated after ligand binding and that this acetylated GR translocates to the nucleus to bind to GRE sites and activate genes, such as SLPI (Ito et al., 2006). Acetylated GR is deacetylated by HDAC2 and this deacetylation is necessary before GR is able to inhibit NF-κB activation of inflammatory genes (Figure 5). The site of acetylation of GR is the lysine rich region –492–495 with the sequence KKTK, which is analogous to the acetylation sites identified on other nuclear hormone receptors. Site-directed mutagenesis of the lysine residues K494 and K495 prevents GR acetylation and reduces the activation of the SLPI gene by corticosteroids, whereas repression of NF-κB is unaffected.

Figure 5.

Acetylation of GR. Binding of a corticosteroid to GR results in its acetylation by HAT, such as CBP, and a dimmer of acetylated GR then binds to GRE to activate or suppress genes (such as side effect genes). Deacetylation of GR by HDAC2 is necessary for GR to interact with CBP and inhibit NF-κB to switch off inflammatory genes.

Nontranscriptional effects

Although most of the actions of corticosteroids are mediated by changes in transcription through chromatin remodelling, it is increasingly recognised that they may also affect protein synthesis by reducing the stability of mRNA so that less protein is synthesised. It is increasingly recognised that several inflammatory proteins are regulated post-transcriptionally at the level of mRNA stability (Anderson et al., 2004). This may be an important anti-inflammatory mechanism as it allows corticosteroids to switch off the ongoing production of inflammatory proteins after the inflammatory gene has been activated. The stability of some inflammatory genes is determined by regulation of AU-rich elements (ARE) in the 3′-untranslated regions of the gene which interact with several ARE binding proteins, such as HuR and tristetraprolin (TTP) that may stabilise mRNA (Raghavan et al., 2001; Dean et al., 2004). Some inflammatory genes, such as the genes encoding GM-CSF and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX2), produce mRNA that is particularly susceptible to the action of ribonucleases that break down mRNA, thus switching off protein synthesis. Corticosteroids may have inhibitory effects on the proteins that stabilise mRNA, leading to more rapid breakdown and thus a reduction in inflammatory protein expression (Newton et al., 1998b; Bergmann et al., 2000; Newton et al., 2001). Corticosteroids do not appear to have any effect on HuR or TTP expression; however, (Bergmann et al., 2004), although a recent report indicate that corticosteroids may suppress TTP gene expression through a nongenomic mechanism, potentially destabilising certain inflammatory gene mRNAs (Jalonen et al., 2005).

Corticosteroid resistance in COPD

Although inhaled corticosteroids are highly effective in asthma, they provide relatively little therapeutic benefit in COPD, despite the fact that active airway and lung inflammation is present. This may reflect that the inflammation in COPD is not suppressed by corticosteroids, with no reduction in inflammatory cells, cytokines or proteases in induced sputum even with high doses of inhaled and oral corticosteroids (Keatings et al., 1997; Culpitt et al., 1999; Loppow et al., 2001). Furthermore, histological analysis of peripheral airways of patients with severe COPD shows an intense inflammatory response, despite treatment with high doses of inhaled corticosteroids (Hogg et al., 2004). There is increasing evidence for an active steroid resistance mechanism in COPD, as corticosteroids fail to inhibit cytokines (such as IL-8 and TNF-α) that they normally suppress (Keatings et al., 1997; Culpitt et al., 1999). In vitro studies show that cytokine release from alveolar macrophages is markedly resistant to the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids, compared to cells from normal smokers and these in turn are more resistant than alveolar macrophages from nonsmokers (Lim et al., 2000; Culpitt et al., 2003). This lack of response to corticosteroids may be explained, at least in part, by an inhibitory effect of cigarette smoking and oxidative stress on HDAC function, thus interfering with the critical anti-inflammatory action of corticosteroids (Ito et al., 2001b; Ito et al., 2005). Indeed, there is a correlation between HDAC activity and the suppressive effects of a corticosteroid on cytokine release. The reduced HDAC2 expression in alveolar macrophages in COPD patients can be restored by inducing overexpression of HDAC2 using a viral vector and this is associated with restoration of corticosteroid responsiveness in these cells (Ito et al., 2006). By contrast, transfection with an HDAC1 vector failed to restore corticosteroid responsiveness in COPD cells.

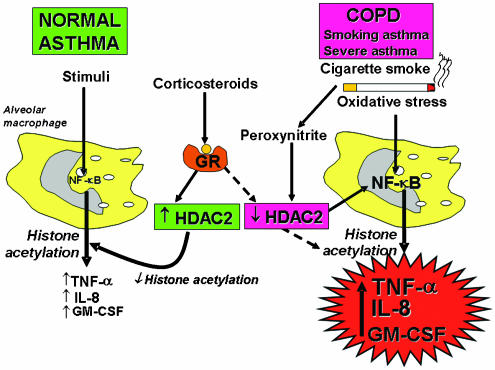

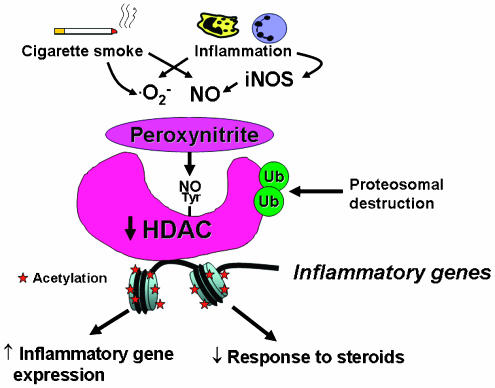

There is increased oxidative and nitrative stress in patients with COPD (Montuschi et al., 2000; Brindicci et al., 2005). It is likely that oxidative and nitrative stress in COPD specifically impairs HDAC2 (Ito et al., 2004; Adcock et al., 2005), resulting in corticosteroid resistance (Barnes et al., 2004) (Figure 6). Although this is seen in all stages of COPD it is most marked in the patients with the most severe disease when HDAC2 expression is reduced by more than 95% compared to nonsmokers (Ito et al., 2005). Even in patients with COPD who have stopped smoking the steroid resistance persists (Keatings et al., 1997; Culpitt et al., 1999) and these patients are known to have continuing oxidative stress (Montuschi et al., 2000). Oxidative stress in the presence of increased nitric oxide production results in the formation of peroxynitrite, which may then nitrate certain tyrosine residues on proteins. Peroxynitrite markedly reduces the anti-inflammatory effect of corticosteroids (Ito et al., 2004) (Figure 7). We have demonstrated that HDAC2 is tyrosine nitrated in COPD lungs and macrophages and that this impairs its catalytic activity (Ito et al., 2004). We have also demonstrated that nitration of HDAC2 targets it for ubiquitination and destruction by the proteasome, resulting in the low protein levels found in COPD patients.

Figure 6.

A proposed mechanism of corticosteroid resistance in COPD, severe asthma and smoking asthma. Stimulation of normal and asthmatic alveolar macrophages activates NF-κB and other transcription factors to switch on HAT leading to histone acetylation and subsequently to transcription of genes encoding inflammatory proteins, such as TNF-α, IL-8 and GM-CSF. Corticosteroids reverse this by binding to GR and recruiting HDAC2. This reverses the histone acetylation induced by NF-κB and switches off the activated inflammatory genes. In COPD and smoking asthmatic patients cigarette smoke generates oxidative stress (acting through the formation of peroxynitrite) to impair the activity of HDAC2. This amplifies the inflammatory response to NF-κB activation, but also reduces the anti-inflammatory effect of corticosteroids, as HDAC2 is now unable to reverse histone acetylation. A similar mechanism may operate in severe asthma where increased oxidative stress is generated by airway inflammation.

Figure 7.

Possible mechanism of HDAC2 inactivation in COPD and smoking asthmatics. Cigarette smoking and inflammation in COPD lungs generates superoxide anions (O2−) and nitric oxide (NO) from iNOS, which combine to form peroxynitrite. Peroxynitrite nitrates certain tyrosine residues (Tyr) and this may inactive the catalytic activity of HDAC2 and also mark the enzyme for ubiquitination (Ub), resulting in destruction by the proteasome. This loss of HDAC2 results in increased histone acetylation, leading to amplification of inflammation and blocking the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids.

The reduction in HDAC2 also prevents deacetylation of acetylated GR so that corticosteroids are no longer able to repress NF-κB-activated inflammatory genes which required deacetylation of the liganded receptor (Ito et al., 2006). Moreover, this results in excessive acetylated GR that may then bind to GRE sites to induce side effect genes. This means that in COPD patients, where there is a reduction in acetylated GR (unpublished observations), not only is the anti-inflammatory action of corticosteroids lost, but side effects more be seen more frequently.

Severe asthma

Patients with severe asthma require much higher doses of inhaled corticosteroids and sometimes maintenance doses of oral corticosteroids for control of asthma symptoms. Oxidative stress is increased in patients with severe asthma and during exacerbations (Montuschi et al., 1999; Caramori & Papi, 2004), so that a reduction in HDAC may also account for the reduced responsiveness to corticosteroids in these patients and the relative unresponsiveness of acute exacerbation of asthma to corticosteroids. There is evidence for reduced HDAC activity in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of patients with severe compare to mild asthma (Cosio et al., 2004a).

Smoking asthmatics

Asthmatic patients who smoke have more severe disease and are also resistant to the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids (Chalmers et al., 2001; Chaudhuri et al., 2003; Thomson & Spears, 2005). A plausible explanation for this steroid resistance is the combined effect of asthma and cigarette smoking on HDAC, resulting in a marked reduction comparable to that seen in COPD patients and this is confirmed by our preliminary data (Murahidy et al., 2005).

Other chronic inflammatory diseases

In other chronic inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatic arthritis and inflammatory bowel disease, there is a high degree of oxidative stress that may lead to impaired HDAC activity and reduced corticosteroid responsiveness. Patients with severe inflammatory diseases respond poorly to conventional doses of corticosteroids and may have the same problem in resistance to their anti-inflammatory properties (Chikanza & Kozaci, 2004; Michetti et al., 2005).

Therapeutic implications

Inhaled corticosteroids are now used as first-line therapy for the treatment of persistent asthma in adults and children in many countries, as they are the most effective treatments for asthma currently available. However, at high doses systemic absorption of inhaled corticosteroids may have deleterious effects, so there has been a search for safer steroids for inhalation and even for oral administration.

Dissociated corticosteroids

Most side effects of corticosteroids appear to be due to DNA binding and gene activation (cis-repression), whereas anti-inflammatory effects are predominantly due to inhibition of inflammatory gene expression by NF-κB and other proinflammatory transcription factors through a non-DNA binding mechanism of action mediated via inhibition of HAT activity and HDAC recruitment (trans-repression). This has led to a search for novel corticosteroids that selectively trans-repress without significant trans-activation or cis-repression, thus reducing the potential risk of systemic side effects. As corticosteroids bind to the same GR, this seems at first to be an unlikely possibility, but while DNA binding involved a GR homodimer, interaction with transcription factors AP-1 and NF-κB and coactivators involves only a single GR (Ito et al., 2001a). A separation of trans-activation and trans-repression has been demonstrated using reporter gene constructs in transfected cells using selective mutations of the GR (Heck et al., 1994). In transgenic mice with GR that do not dimerize (dim−/−) there is no trans-activation, but trans-repression appears to be normal (Reichardt et al., 1998, 2001). Furthermore, some steroids, such as the antagonist RU486, have a greater trans-repression than trans-activation effect. Indeed, the topical steroids used in asthma therapy today, such as fluticasone propionate and budesonide, appear to have more potent trans-repression than trans-activation effects, which may account for their selection as potent anti-inflammatory agents (Adcock et al., 1999; Jaffuel et al., 2000). Recently, a novel class of steroids has been described in which there is potent trans-repression with relatively little trans-activation. These ‘dissociated' steroids, including RU24858 and RU40066 have anti-inflammatory effects in vitro (Vayssiere et al., 1997) and in vivo (Schacke et al., 2004). Several dissociated corticosteroids are now in clinical development and may lead to inhaled steroids with greater safety or even to oral steroids which are lees likely to produce significant adverse effects (Miner et al., 2005). The recent resolution of the crystal structure of the ligand binding domain of GR may help in better design of dissociated steroids (Bledsoe et al., 2002).

Reversal of corticosteroid resistance

As oxidative stress and peroxynitrite appear to inhibit HDAC activity and mimic the defect in HDAC seen in COPD patients, antioxidants, inhibitors of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) or peroxynitrite scavengers such as ebselen, might be expected to be effective in restoring corticosteroid responsiveness. New and more effective antioxidants are in development (Cuzzocrea et al., 2004) and selective iNOS inhibitors are already in clinical trials (Hansel et al., 2003).

Theophylline

Theophylline is the first drug that has been shown to activate HDAC, resulting in marked potentiation of the anti-inflammatory effects of corticosteroids (Ito et al., 2002b; Cosio et al., 2004b). This action of theophylline is not mediated via phosphodiesterase inhibition or adenosine receptor antagonism and therefore appears to be a novel action of the drug (Ito et al., 2002b). In COPD macrophages low concentrations of theophylline are able to restore HDAC activity to normal and reverse steroid resistance of thee cells in vitro (Cosio et al., 2004b). Clinical studies to explore this effect of theophylline are now underway (Barnes, 2005b). It may be possible to discover other drugs in this class which could form the basis of a new class of anti-inflammatory drugs without the side effects that limit the use of theophylline (Barnes, 2003) and identification of the signal transduction pathways whereby theophylline activates HDAC and restores HDAC levels to normal may lead to novel anti-inflammatory approaches for the treatment of steroid-resistant inflammatory diseases (Barnes, 2005a).

Conclusions

Corticosteroids exert their anti-inflammatory effects through influencing multiple signal transduction pathways. Their most important action is switching off multiple activated inflammatory genes through inhibition of HAT and recruitment of HDAC2 activity to the inflammatory gene transcriptional complex. HDAC2 may play an important role in deacetylating the acetylated GR after corticosteroid binding so that it can repress NF-κB regulated inflammatory genes. In addition, corticosteroids may activate several anti-inflammatory genes and increase the degradation of mRNA encoding certain inflammatory proteins. This broad array of actions may account for the striking efficacy of corticosteroids in complex inflammatory diseases, such as asthma and rheumatoid arthritis, and the difficulty in finding alternative anti-inflammatory drugs. There is now a better understanding of how the responsiveness to corticosteroids is reduced in severe asthma, asthmatic patients who smoke and in patients with COPD. An important mechanism now emerging is a reduction in HDAC2 activity as a result of oxidative and nitrative stress. These new insights into corticosteroid action may lead to new approaches to treating inflammatory lung diseases and in particular to increasing efficacy of steroids in situations where they are less effective.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge the contributions of many researchers within my department, which have contributed to the novel mechanisms of corticosteroids discussed in this review, and particularly those of Dr Kazuhiro Ito and Professor Ian Adcock. I also acknowledge generous funding from the Wellcome Trust, Medical Research Council (U.K.), Asthma U.K., British Lung Foundation, GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca and Mitsubishi Pharma.

Abbreviations

- AP-1

activator protein-1

- CBP

cyclic AMP response element binding (CREB) binding protein

- COPD

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COX

cyclooxygenase

- GM-CSF

granulocyte–macrophage colony stimulating factor

- GR

glucocorticoid receptor

- HAT

histone acetyltransferase

- HDAC

histone deacetylase

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappaB

- SLPI

secretory leukoprotease inhibitor

- TNF

tumour necrosis factor

- TTP

tristetraprolin

References

- ADCOCK I.M., COSIO B., TSAPROUNI L., BARNES P.J., ITO K. Redox regulation of histone deacetylases and glucocorticoid-mediated inhibition of the inflammatory response. Antioxid. Redox. Signal. 2005;7:144–152. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ADCOCK I.M., NASUHARA Y., STEVENS D.A., BARNES P.J. Ligand-induced differentiation of glucocorticoid receptor trans-repression and transactivation: preferential targetting of NF-κB and lack of I-κB involvement. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;127:1003–1011. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ANDERSON P., PHILLIPS K., STOECKLIN G., KEDERSHA N. Post-transcriptional regulation of proinflammatory proteins. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2004;76:42–47. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNISTER A.J., SCHNEIDER R., KOUZARIDES T. Histone methylation: dynamic or static. Cell. 2002;109:801–806. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00798-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Theophylline: new perspectives on an old drug. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167:813–818. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200210-1142PP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Distribution of receptor targets in the lung. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2004a;1:345–351. doi: 10.1513/pats.200409-045MS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Mediators of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharm. Rev. 2004b;56:515–548. doi: 10.1124/pr.56.4.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Targeting histone deacetylase 2 in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease treatment. Expert. Opin. Ther. Targets. 2005a;9:1111–1121. doi: 10.1517/14728222.9.6.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J. Theophylline in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: new horizons. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005b;2:334–339. doi: 10.1513/pats.200504-024SR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Transcription factors and asthma. Eur. Respir. J. 1998;12:221–234. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12010221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. How do corticosteroids work in asthma. Ann. Intern. Med. 2003;139:359–370. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-5_part_1-200309020-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F., PAGE C.P. Inflammatory mediators of asthma: an update. Pharmacol. Rev. 1998;50:515–596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., ITO K., ADCOCK I.M. A mechanism of corticosteroid resistance in COPD: inactivation of histone deacetylase. Lancet. 2004;363:731–733. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15650-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARNES P.J., KARIN M. Nuclear factor-κB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. New Engl. J. Med. 1997;336:1066–1071. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704103361506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGER S.L. An embarrassment of niches: the many covalent modifications of histones in transcriptional regulation. Oncogene. 2001;20:3007–3013. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGMANN M., BARNES P.J., NEWTON R. Molecular regulation of granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor in human lung epithelial cells by interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-4, and IL-13 involves both transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2000;22:582–589. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.5.3889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BERGMANN M.W., STAPLES K.J., SMITH S.J., BARNES P.J., NEWTON R. Glucocorticoid inhibition of GM-CSF from T cells is independent of control by NF-kB and CLE0. Am. J. Respir. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2004;30:555–563. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0295OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BLEDSOE R.K., MONTANA V.G., STANLEY T.B., DELVES C.J., APOLITO C.J., MCKEE D.D., CONSLER T.G., PARKS D.J., STEWART E.L., WILLSON T.M., LAMBERT M.H., MOORE J.T., PEARCE K.H., XU H.E. Crystal structure of the glucocorticoid receptor ligand binding domain reveals a novel mode of receptor dimerization and coactivator recognition. Cell. 2002;110:93–105. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOARDLEY J.E., CAREY R.A., HARVEY A.M. Preliminary observations on the effect of adrenocorticotropic hormone in allergic diseases. Bull. Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1949;85:396–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BODWELL J.E., WEBSTER J.C., JEWELL C.M., CIDLOWSKI J.A., HU J.M., MUNCK A. Glucocorticoid receptor phosphorylation: overview, function and cell cycle-dependence. J. Steroid. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1998;65:91–99. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(97)00185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRINDICCI C., ITO K., RESTA O., PRIDE N.B., BARNES P.J., KHARITONOV S.A. Exhaled nitric oxide from lung periphery is increased in COPD. Eur. Respir. J. 2005;26:52–59. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00125304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN H.M., STOREY G., GEORGE W.H. Beclomethasone dipropionate: a new steroid aerosol for the treatment of allergic asthma. Br. Med. J. 1972;1:585–590. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5800.585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARAMORI G., PAPI A. Oxidants and asthma. Thorax. 2004;59:170–173. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2002.002477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHALMERS G.W., MACLEOD K.J., THOMSON L., LITTLE S.A., MCSHARRY C., THOMSON N.C. Smoking and airway inflammation in patients with mild asthma. Chest. 2001;120:1917–1922. doi: 10.1378/chest.120.6.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHAUDHURI R., LIVINGSTON E., MCMAHON A.D., THOMSON L., BORLAND W., THOMSON N.C. Cigarette smoking impairs the therapeutic response to oral corticosteroids in chronic asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:1265–1266. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200304-503OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHIKANZA I.C., KOZACI D.L. Corticosteroid resistance in rheumatoid arthritis: molecular and cellular perspectives. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1337–1345. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSIO B.G., MANN B., ITO K., JAZRAWI E., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F., ADCOCK I.M. Histone acetylase and deacetylase activity in alveolar macrophages and blood monocytes in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2004a;170:141–147. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200305-659OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COSIO B.G., TSAPROUNI L., ITO K., JAZRAWI E., ADCOCK I.M., BARNES P.J. Theophylline restores histone deacetylase activity and steroid responses in COPD macrophages. J. Exp. Med. 2004b;200:689–695. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CULPITT S.V., NIGHTINGALE J.A., BARNES P.J. Effect of high dose inhaled steroid on cells, cytokines and proteases in induced sputum in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;160:1635–1639. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.5.9811058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CULPITT S.V., ROGERS D.F., SHAH P., DE MATOS C., RUSSELL R.E., DONNELLY L.E., BARNES P.J. Impaired inhibition by dexamethasone of cytokine release by alveolar macrophages from patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2003;167:24–31. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-298OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CUZZOCREA S., THIEMERMANN C., SALVEMINI D. Potential therapeutic effect of antioxidant therapy in shock and inflammation. Curr. Med. Chem. 2004;11:1147–1162. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DE RUIJTER A.J., VAN GENNIP A.H., CARON H.N., KEMP S., VAN KUILENBURG A.B. Histone deacetylases (HDACs): characterization of the classical HDAC family. Biochem. J. 2003;370:737–749. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEAN J.L., SULLY G., CLARK A.R., SAKLATVALA J. The involvement of AU-rich element-binding proteins in p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway-mediated mRNA stabilisation. Cell. Signal. 2004;16:1113–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DI STEFANO A., CARAMORI G., CAPELLI A., LUSUARDI M., GNEMMI I., IOLI F., CHUNG K.F., DONNER C.F., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Increased expression of NF-kB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur. Resp. J. 2002;20:556–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.02.00272002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DOSTERT A., HEINZEL T. Negative glucocorticoid receptor response elements and their role in glucocorticoid action. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2004;10:2807–2816. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FU M., WANG C., ZHANG X., PESTELL R.G. Acetylation of nuclear receptors in cellular growth and apoptosis. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:1199–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GLOZAK M.A., SENGUPTA N., ZHANG X., SETO E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene. 2005;363:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HALL S.E., LIM S., WITHERDEN I.R., TETLEY T.D., BARNES P.J., KAMAL A.M., SMITH S.F. Lung type II cell and macrophage annexin I release: differential effects of two glucocorticoids. Am. J. Physiol. 1999;276:L114–L121. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.1.L114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANSEL T.T., KHARITONOV S.A., DONNELLY L.E., ERIN E.M., CURRIE M.G., MOORE W.M., MANNING P.T., RECKER D.P., BARNES P.J. A selective inhibitor of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibits exhaled breath nitric oxide in healthy volunteers and asthmatics. FASEB. J. 2003;17:1298–1300. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0633fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HART L., LIM S., ADCOCK I., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F. Effects of inhaled corticosteroid therapy on expression and DNA-binding activity of nuclear factor-kB in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;161:224–231. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.1.9809019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HART L.A., KRISHNAN V.L., ADCOCK I.M., BARNES P.J., CHUNG K.F. Activation and localization of transcription factor, nuclear factor-κB, in asthma. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1998;158:1585–1592. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9706116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECHT K., CARLSTEDT-DUKE J., STIERNA P., GUSTAFFSON J.-Å., BRONNEGARD M., WILKSTROM A.-C. Evidence that the β-isoform of the human glucocorticoid receptor does not act as a physiologically significant repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:26659–26664. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECK S., BENDER K., KULLMANN M., GOTTLICHER M., HERRLICH P., CATO A.C. IκB alpha-independent downregulation of NF-κB activity by glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO. J. 1997;16:4698–4707. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.15.4698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HECK S., KULLMANN M., GRAST A., PONTA H., RAHMSDORF H.J., HERRLICH P., CATO A.C.B. A distinct modulating domain in glucocorticoid receptor monomers in the repression of activity of the transcription factor AP-1. EMBO. J. 1994;13:4087–4095. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06726.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOGG J.C., CHU F., UTOKAPARCH S., WOODS R., ELLIOTT W.M., BUZATU L., CHERNIACK R.M., ROGERS R.M., SCIURBA F.C., COXSON H.O., PARE P.D. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IMHOF A., WOLFFE A.P. Transcription: gene control by targeted histone acetylation. Curr. Biol. 1998;8:R422–R424. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISMAILI N., GARABEDIAN M.J. Modulation of glucocorticoid receptor function via phosphorylation. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2004;1024:86–101. doi: 10.1196/annals.1321.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Glucocorticoid receptor recruitment of histone deacetylase 2 inhibits IL-1b-induced histone H4 acetylation on lysines 8 and 12. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2000;20:6891–6903. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.18.6891-6903.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., CARAMORI G., LIM S., OATES T., CHUNG K.F., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Expression and activity of histone deacetylases (HDACs) in human asthmatic airways. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2002a;166:392–396. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., ITO M., ELLIOTT W.M., COSIO B., CARAMORI G., KON O.M., BARCZYK A., HAYASHI M., ADCOCK I.M., HOGG J.C., BARNES P.J. Decreased histone deacetylase activity in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;352:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., JAZRAWI E., COSIO B., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. p65-activated histone acetyltransferase activity is repressed by glucocorticoids: Mifepristone fails to recruit HDAC2 to the p65/HAT complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2001a;276:30208–30215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., LIM S., CARAMORI G., CHUNG K.F., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Cigarette smoking reduces histone deacetylase 2 expression, enhances cytokine expression and inhibits glucocorticoid actions in alveolar macrophages. FASEB. J. 2001b;15:1100–1102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., LIM S., CARAMORI G., COSIO B., CHUNG K.F., ADCOCK I.M., BARNES P.J. A molecular mechanism of action of theophylline: Induction of histone deacetylase activity to decrease inflammatory gene expression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002b;99:8921–8926. doi: 10.1073/pnas.132556899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., TOMITA T., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Oxidative stress reduces histone deacetylase (HDAC)2 activity and enhances IL-8 gene expression: role of tyrosine nitration. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2004;315:240–245. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ITO K., YAMAMURA S., ESSILFIE-QUAYE S., COSIO B., ITO M., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. Histone deacetylase 2-mediated deacetylation of the glucocorticoid receptor enables NF-kB suppression. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:7–13. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAFFUEL D., DEMOLY P., GOUGAT C., BALAGUER P., MAUTINO G., GODARD P., BOUSQUET J., MATHIEU M. Transcriptional potencies of inhaled glucocorticoids. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:57–63. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.1.9901006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JALONEN U., LAHTI A., KORHONEN R., KANKAANRANTA H., MOILANEN E. Inhibition of tristetraprolin expression by dexamethasone in activated macrophages. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2005;69:733–740. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAGOSHIMA M., WILCKE T., ITO K., TSAPROUNI L., BARNES P.J., PUNCHARD N., ADCOCK I.M. Glucocorticoid-mediated transrepression is regulated by histone acetylation and DNA methylation. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;429:327–334. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01332-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KEATINGS V.M., JATAKANON A., WORSDELL Y.M., BARNES P.J. Effects of inhaled and oral glucocorticoids on inflammatory indices in asthma and COPD. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1997;155:542–548. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.2.9032192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KURIHARA I., SHIBATA H., SUZUKI T., ANDO T., KOBAYASHI S., HAYASHI M., SAITO I., SARUTA T. Expression and regulation of nuclear receptor coactivators in glucocorticoid action. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 2002;189:181–189. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00717-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LASA M., ABRAHAM S.M., BOUCHERON C., SAKLATVALA J., CLARK A.R. Dexamethasone causes sustained expression of mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) phosphatase 1 and phosphatase-mediated inhibition of MAPK p38. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:7802–7811. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.7802-7811.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEE K.-Y., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. NF-kB and AP-1 response elements and the role of histone modifications in IL-1b-induced TGF-b1 gene transcription. J. Immunol. 2006;176:603–615. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.1.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEUNG D.Y.M., HAMID Q., VOTTERO A., SZEFLER S.J., SURS W., MINSHALL E., CHROUSOS G.P., KLEMM D.J. Association of glucocorticoid insensitivity with increased expression of glucocorticoid receptor b. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:1567–1574. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LI X., WONG J., TSAI S.Y., TSAI M.J., O'MALLEY B.W. Progesterone and glucocorticoid receptors recruit distinct coactivator complexes and promote distinct patterns of local chromatin modification. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2003;23:3763–3773. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.11.3763-3773.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIM S., ROCHE N., OLIVER B.G., MATTOS W., BARNES P.J., FAN C.K. Balance of matrix metalloprotease-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloprotease-1 from alveolar macrophages in cigarette smokers. regulation by interleukin-10. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:1355–1360. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.4.9910097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOPPOW D., SCHLEISS M.B., KANNIESS F., TAUBE C., JORRES R.A., MAGNUSSEN H. In patients with chronic bronchitis a four week trial with inhaled steroids does not attenuate airway inflammation. Respir. Med. 2001;95:115–121. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MICHETTI P., MOTTET C., JUILLERAT P., FELLEY C., VADER J.P., BURNAND B., GONVERS J.J., FROEHLICH F. Severe and steroid-resistant Crohn's disease. Digestion. 2005;71:19–25. doi: 10.1159/000083867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MINER J.N., HONG M.H., NEGRO-VILAR A. New and improved glucocorticoid receptor ligands. Expert. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2005;14:1527–1545. doi: 10.1517/13543784.14.12.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MITTELSTADT P.R., ASHWELL J.D. Inhibition of AP-1 by the glucocorticoid-inducible protein GILZ. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:29603–29610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONACO C., PALEOLOG E. Nuclear factor kappaB: a potential therapeutic target in atherosclerosis and thrombosis. Cardiovasc. Res. 2004;61:671–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2003.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTUSCHI P., CIABATTONI G., CORRADI M., NIGHTINGALE J.A., COLLINS J.V., KHARITONOV S.A., BARNES P.J. Increased 8-Isoprostane, a marker of oxidative stress, in exhaled condensates of asthmatic patients. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1999;160:216–220. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.160.1.9809140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MONTUSCHI P., COLLINS J.V., CIABATTONI G., LAZZERI N., CORRADI M., KHARITONOV S.A., BARNES P.J. Exhaled 8-isoprostane as an in vivo biomarker of lung oxidative stress in patients with COPD and healthy smokers. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2000;162:1175–1177. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.3.2001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER-LADNER U., GAY R.E., GAY S. Role of nuclear factor kB in synovial inflammation. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2002;4:201–207. doi: 10.1007/s11926-002-0066-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MURAHIDY A., ITO M., ADCOCK I.M., BARNES P.J., ITO K. Reduction is histone deacetylase expression and activity in smoking asthmatics: a mechanism of steroid resistance. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2005;2:A889. [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON R., HART L.A., STEVENS D.A., BERGMANN M., DONNELLY L.E., ADCOCK I.M., BARNES P.J. Effect of dexamethasone on interleukin-1β-induced nuclear factor-κB and κB-dependent transcription in epithelial cells. Eur. J. Biochem. 1998a;254:81–89. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2540081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON R., SEYBOLD J., KUITERT L.M.E., BERGMANN M., BARNES P.J. Repression of cyclooxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2 release by dexamethasone occurs by transcriptional and post-transcriptional mechanisms Involving loss of polyadenylated mRNA. J. Biol. Chem. 1998b;273:32312–32321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.32312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NEWTON R., STAPLES K.J., HART L., BARNES P.J., BERGMANN M.W. GM-CSF expression in pulmonary epithelial cells is regulated negatively by posttranscriptional mechanisms. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;287:249–253. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSON C.L. HDAC's at work: everyone doing their part. Mol. Cell. 2002;9:921–922. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00534-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PETERSON C.L., LANIEL M.A. Histones and histone modifications. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R546–R551. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRIVALSKY M.L. The role of corepressors in transcriptional regulation by nuclear hormone receptors. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2004;66:315–360. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.66.032802.155556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PUJOLS L., MULLOL J., ROCA-FERRER J., TORREGO A., XAUBET A., CIDLOWSKI J.A., PICADO C. Expression of glucocorticoid receptor alpha- and beta-isoforms in human cells and tissues. Am. J. Physiol. Cell. Physiol. 2002;283:C1324–C1331. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00363.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAGHAVAN A., ROBISON R.L., MCNABB J., MILLER C.R., WILLIAMS D.A., BOHJANEN P.R. HuA and tristetraprolin are induced following T cell activation and display distinct but overlapping RNA binding specificities. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:47958–47965. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109511200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REICHARDT H.M., KAESTNER K.H., TUCKERMANN J., KRETZ O., WESSELY O., BOCK R., GASS P., SCHMID W., HERRLICH P., ANGEL P., SCHUTZ G. DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell. 1998;93:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- REICHARDT H.M., TUCKERMANN J.P., GOTTLICHER M., VUJIC M., WEIH F., ANGEL P., HERRLICH P., SCHUTZ G. Repression of inflammatory responses in the absence of DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO. J. 2001;20:7168–7173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RHEN T., CIDLOWSKI J.A. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids – new mechanisms for old drugs. New Engl. J. Med. 2005;353:1711–1723. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ROTH S.Y., DENU J.M., ALLIS C.D. Histone acetyltransferases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2001;70:81–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHACKE H., SCHOTTELIUS A., DOCKE W.D., STREHLKE P., JAROCH S., SCHMEES N., REHWINKEL H., HENNEKES H., ASADULLAH K. Dissociation of transactivation from transrepression by a selective glucocorticoid receptor agonist leads to separation of therapeutic effects from side effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:227–232. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0300372101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THIAGALINGAM S., CHENG K.H., LEE H.J., MINEVA N., THIAGALINGAM A., PONTE J.F. Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 2003;983:84–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2003.tb05964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMSON N.C., SPEARS M. The influence of smoking on the treatment response in patients with asthma. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2005;5:57–63. doi: 10.1097/00130832-200502000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAYSSIERE B.M., DUPONT S., CHOQUART A., PETIT F., GARCIA T., MARCHANDEAU C., GRONEMEYER H., RESCHE-RIGON M. Synthetic glucocorticoids that dissociate transactivation and AP-1 transrepression exhibit antiinflammatory activity in vivo. Mol. Endocrinol. 1997;11:1245–1255. doi: 10.1210/mend.11.9.9979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WADA H., KAGOSHIMA M., ITO K., BARNES P.J., ADCOCK I.M. 5-Azacytidine suppresses RNA polymerase II recruitment to the SLPI gene. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;331:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG Y., FISCHLE W., CHEUNG W., JACOBS S., KHORASANIZADEH S., ALLIS C.D. Beyond the double helix: writing and reading the histone code. Novartis Found. Symp. 2004;259:3–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU B., LI P., LIU Y., LOU Z., DING Y., SHU C., YE S., BARTLAM M., SHEN B., RAO Z. 3D structure of human FK506-binding protein 52: implications for the assembly of the glucocorticoid receptor/Hsp90/immunophilin heterocomplex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:8348–8353. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0305969101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO T.P., KU G., ZHOU N., SCULLY R., LIVINGSTON D.M. The nuclear hormone receptor coactivator SRC-1 is a specific target of p300. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:10626–10631. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.20.10626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]