Abstract

The role of the anti-inflammatory protein annexin-A1 (Anx-A1) in the phagocytic process has been investigated using a murine bone marrow culture-derived macrophage model from Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− mice.

Macrophages prepared from Anx-A1−/− mice exhibited a reduced ingestion of zymosan, Neisseria meningitidis or sheep red blood cells, when compared to Anx-A1+/+ cells and in the case of zymosan this effect was also mirrored by a reduced clearance in vivo when particles were injected into the peritoneal cavity of Anx-A1−/− mice.

The ablation of the Anx-A1 gene did not cause any apparent cytoskeletal defects associated with particle ingestion but the cell surface expression of the key adhesion molecule CD11b was depressed in the Anx-A1−/− cells providing a possible explanation for the attenuated phagocytic potential of these cells.

The production of the cytokines TNFα and IL-6 was increased in Anx-A1−/− macrophages following phagocytosis of all types of particle.

Keywords: Annexin A1, Zymosan, N. meningitidis, CD11b, inflammation and cytokines

Introduction

Experiments conducted in the late 1970s investigating the control by glucocorticoids of eicosanoid generation in peritoneal macrophages led to the discovery and cloning of the protein annexin A1 (Anx-A1; formerly lipocortin-1; see Yona et al. (2005) for a review). It is now recognised that this protein belongs to a superfamily of proteins (some 13 have been described in mammals) characterised by a highly homologous core domain comprising four (or sometimes eight) repeats of a 70–75 amino-acid sequence, which confers Ca2+- and phospholipid-binding properties, and an amino-terminal tail which is exclusive to each family member (Gerke & Moss, 2002). Anx-A1 is among the most studied member of this family. Glucocorticoids regulate the synthesis, phosphorylation and cellular disposition of this annexin in several tissues and this has lead to the concept that Anx-A1 could act as a ‘second messenger' of glucocorticoid action.

In early experiments, glucocorticoids were observed to act as potent inhibitors of eicosanoid release from the resident macrophages (Mφ) of the peritoneal cavity (Bray & Gordon, 1978) and a phagocytosis-inhibitory protein released from Mφ treated with glucocorticoids was tentatively identified as being related to ‘lipocortin' by Grasso and his co-workers (Becker & Grasso, 1988; Becker et al., 1988). Following the characterisation of Anx-A1, it was observed that treatment of monocytes and Mφ (Getting, 2002; Goulding, 2004) with the exogenous protein inhibited cellular activation, as assessed by superoxide generation, prostanoid release and inflammatory enzyme or cytokine expression (Maridonneau-Parini et al., 1989; Comera & Russo-Marie, 1995; Wu et al., 1995). More recently, the Anx-A1 mimetic peptide Ac2–26 (Perretti, 1998) was shown to inhibit IgG immune complex phagocytosis by mouse peritoneal Mφ, as determined by flow cytometry (Getting et al., 1997).

To elucidate the role of Anx-A1 under normal physiological conditions and during pathology, we recently generated a line of Anx-A1 null (Anx-A1−/−) mice (Hannon et al., 2003). These mice displayed a heightened sensitivity to both acute (Hannon et al., 2003) and chronic (Yang et al., 2004) inflammatory stimuli coupled with a reduced responsiveness to glucocorticoids. Fibroblasts cloned from tissues taken from the Anx-A1−/− mouse also exhibited a number of differences compared to the wild-type cells, including an increased release of arachidonic acid and eicosanoids in response to EGF and other stimuli, a disordered cell cycle and resistance to the inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids (Croxtall et al., 2003).

In a previous issue of this journal, we reported our initial findings on the effect of Anx-A1 gene deletion on zymosan particle uptake by resident peritoneal Mφ (Yona et al., 2004). In this paper, we have pursued this observation, finding that bone marrow culture-derived (BMD) Anx-A1−/− Mφ exhibit a reduced phagocytic capacity and an exacerbated release of cytokines following the addition of inflammatory stimuli.

Methods

Animals and BMD macrophages (BMDMφ)

Anx-A1−/− and wild-type littermate control (Anx-A1+/+) mice were bred in-house (Hannon et al., 2003). All animals were fed on a standard chow pellet diet with free access to water and maintained on a 12-h light–dark cycle. Animal work was performed in accordance with U.K. Home Office regulations, Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986.

Mice 4–6 weeks old were killed, the femur was excised, and the epiphyses removed prior to flushing out the bone marrow. Cells were washed and resuspended in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4, 10% foetal calf serum (FCS) and 15% L929 cell-conditioned media and cells were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air for 7 days. On day 7, BMDMφ cultures were detached with PBS supplemented with 10 mM EDTA and 4 mg ml−1 lidocaine and plated in appropriate dishes for each assay.

Cell surface marker expression

Aliquots (250 μl) of a BMDMφ preparation, 1 × 106 cells ml−1 in PBC (PBS, 1 mM Ca2+ and 0.2 mg ml−1 bovine serum albumin (BSA)), were plated into 96-well plates together with 20 μl blocking human IgG (16 mg ml−1), 5% goat serum and 20 μl of either rat anti-mouse CD11b (0.8 μg ml−1), rat anti-mouse F4/80 (5 μg ml−1) or rat anti-mouse FcγRIII/II (5 μg ml−1). Following 45 min incubation at 4°C, cells were washed and stained with 40 μl of FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-rat IgG antibody (1 : 80 dilution) for 30 min at 4°C. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Cowley, U.K.) with an air-cooled 100 mW argon ion laser tuned to 488 nm connected to an Apple MAC G3 computer running Cell Quest II software. The number of molecules of endogenous antigen per sample was quantified by acquiring 10,000 events in the FL-1 channel (wavelength of 548 nm), and calculated as median fluorescence intensity (MFI) units.

Cytokine release

BMDMφ's (0.5 × 106 well−1) were incubated in 24-well plates and cultured for 24 h at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air. Adherent cells were washed and incubated with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS, prior to stimulation with either boiled zymosan (at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 : 50), ethanol-fixed Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B (MC58; at an MOI of 1 : 50) or 10 ng ml−1 LPS. Cell-free supernatants were collected at various time points. These samples were then frozen at −80°C prior to detection of release of proinflammatory cytokines, IL-6 and TNFα, using commercially available enzyme immunoassay reagents.

Assays of BMDMφ phagocytosis

The extent of particle association with, and ingestion by, cells (as opposed to ingestion alone) was investigated using FITC-labelled zymosan, rhodamine green X-labelled N. meningitidis or FITC-labelled opsonised sheep red blood cells. Fluorescent particles were added to 1 × 106 macrophages at time 0 and incubated at 37°C; the Fluorescent-particle amount was calibrated to five particles per macrophage in order to reduce spill-over fluorescence. At different times, phagocytosis was halted by washing cells with 500 μl PBS supplemented with 2 mM EDTA and 4 mg ml−1 lidocaine hydrochloride prior to fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde. Samples were placed in an ice bath and analysed within 1 h by flow cytometry. The assay used above does not distinguish between binding and ingestion. Attempts to adjust the flow cytometric assay protocol to measure ingestion alone by trypan blue or ethidium bromide quenching (Drevets & Campbell, 1991; Giaimis et al., 1994) of extracellular fluorescence proved to be ineffective in our hands (data not shown). Repetitive washing of the cells removed most unbound fluorescently labelled particles.

In order to measure phagocytosis in vivo, FITC-labelled zymosan (2.3 × 107 particles mouse−1) was injected i.p. in both Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− mice. The uptake over time was measured by cellular fluorescence, as described above. The animals were killed at 0, 2, 10 and 20 min following the i.p. injection of FITC-labelled zymosan and the cells in the peritoneal cavity recovered by lavage with 3 ml PBS/EDTA. Samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and kept on ice. Flow cytometry was performed using a FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Cowley, U.K.) as described previously. The mean fluorescence of unloaded control cells was subtracted from the mean fluorescence of each assay condition, and the average was determined.

Real-time confocal analysis

Real-time confocal microscopy was used to visualise the kinetic events involved during phagocytosis. BMDMφ were resuspended to 2 × 105 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4. Then, 500 μl of cell suspension was added to each coverslip. Following overnight incubation at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air, the coverslips were washed three times with 1.5 ml of tissue culture grade PBS to ensure removal of any cell debris. Cells were then incubated again with RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air and placed on warmed stage to allow visualisation of cells by confocal microscopy. FITC-conjugated zymosan particles were added at an MOI of 1 : 5. Analysis by confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed using LaserSharp software, cells were mounted on a 2000 MP BioRAD™ microscope and images captured over a 1 h period every 15 s. Recordings were saved as QuickTime™ movie documents and played back for analysis.

To establish the role of Anx-A1 during phagocytosis, BMDMφ were resuspended to a concentration of 2 × 106 cells ml−1 in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FCS and 25 mM HEPES pH 7.4. Cell suspension (500 μl) was seeded onto the glass coverslips in 24-well plates. Following overnight incubation at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air, the plate was placed on ice and wells were washed three times with 1.5 ml of tissue culture grade PBS to ensure removal of any cell debris. FITC-conjugated zymosan particles were added to each well at an MOI of 1 : 5 for 1 h on ice, to allow for cell to particle adhesion but not phagocytosis. Following 1 h incubation on ice, wells were washed three times with ice-cold RPMI 1640 to remove nonadherent zymosan particles. Plates were then incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air, for 5 min to monitor phagocytic cup formation. Coverslips were then washed twice with ice-cold PBS, prior to the addition of ice-cold PBS supplemented with 4% paraformaldehyde solution and 200 mM HEPES buffer to fix the cells for at least 15 min. Cells were then permeabilised for 30 min at room temperature using PBS supplemented with 0.25% saponin, 1% BSA and 1% goat serum. Using this buffer, cells were first washed with the staining solution prior to being incubated at room temperature with a rabbit anti-Anx-A1 primary antibody (1 : 1000 dilution) for 1 h (which recognises the full-length Anx-A1). Cells were then washed three times before incubation with TRITC phalloidin (1 : 100 dilution of stock) and AlexaFluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 150 dilution), the secondary antibody for Anx-A1 for 1 h at room temperature; coverslips were washed four times prior to mounting. Analysis by confocal laser scanning microscopy was performed using LaserSharp software mounted on a 2000 MP BioRAD™ microscope. Representative pictures of slides were collected and saved in a QuickTime™ format, prior to being imported to Adobe Photoshop™ 7.0 software for single colour analysis.

Chemicals

The following items were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Poole, Dorset, U.K.), BSA, calcium chloride, EDTA, goat serum, human IgG, lidocaine hydrochloride, lipopolysaccharide (0111:B4), paraformaldehyde, phosphate buffer saline tablets, Saponin Saponaria species S2149, sheep red blood cells, anti-sheep red blood cell stroma (S1389), TRITC phalloidin and zymosan A. Foetal calf serum, HEPES buffer, RPMI 1640 were purchased from GIBCO BRL (Paisley, Scotland, U.K.). Rat-anti-mouse CD11b (clone 5C6) was a generous gift from Dr N Gozzard, Celltech (Slough, U.K.). Rat-anti-mouse F4/80 (clone Cl:A31) and FITC-conjugated rabbit anti-rat IgG antibody were purchased from Serotec (Kidlington, Oxford, U.K.). OptEIA™ Elisa kits for TNFα or IL-6 and Rat-anti-mouse FcγRIII/II were purchased from BD PharMingen (Cowley, Oxford, U.K.). Rabbit anti-annexin-1 polyclonal antibody (71–3400) was purchased from ZYMED Laboratories Inc. (Cambridge, U.K.). AlexaFluor 647 goat anti-rabbit IgG, Fluorescein-labelled zymosan and Slowfade™ were purchased from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, U.S.A.). All other chemicals were of analytical grade.

Statistical analysis

In all cases, data are expressed as mean±s.e.m. of n distinct experiments. Statistical differences among groups were analysed by Student's t-test. A probability value <0.05 was accepted to reject the null hypothesis.

Results

Cell surface marker expression

There were reductions in the cell surface expression of all cell surface markers measured in Anx-A1−/− cells, but this only achieved significance in the case of CD11b which was reduced by approximately 25% when compared to Anx-A1+/+ controls (see Table 1). This is congruent with our earlier findings showing a reduction in CD11b on circulating cells in Anx-A1−/− mice (Hannon et al., 2003).

Table 1.

Expression of cell surface markers on Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ

| Genotype | FcRγII/III | CD11b | F4/80 |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Anx-A1+/+ |

170±6 |

215±8 |

128±16 |

| Anx-A1−/− | 156±7 | 160±5* | 111±17 |

Macrophages labelled with either anti-FcRγIII/II (clone: 2.4G2), anti-F4/80 (clone Cl:A31) or anti-CD11b (clone: 5C6) prior to the addition of an FITC secondary antibody. Cell surface markers were measured by flow cytometry. All data are mean±s.e.m. of n=4–5 experiments performed with n=4–5 mice each. *P<0.05 vs Anx-A1+/+ cells expression.

P<0.05.

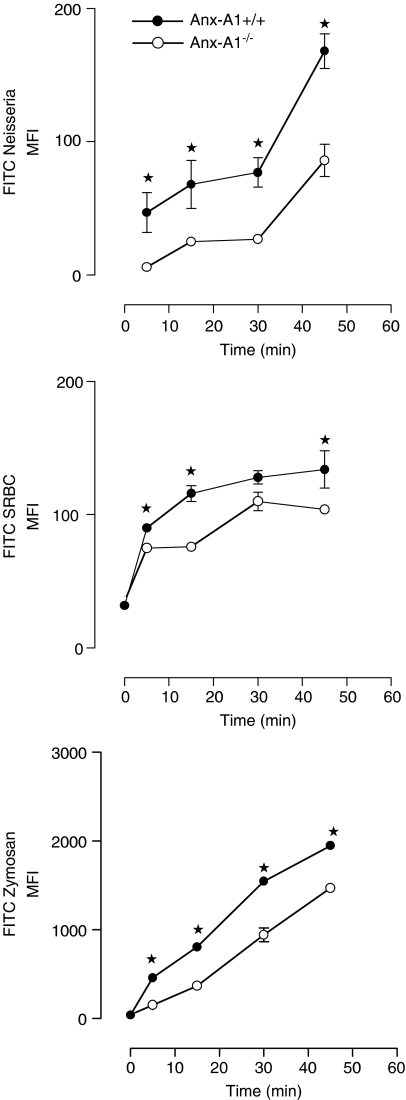

BMDMφ particle uptake both in vitro and in vivo

Uptake of rhodamine green X-labelled N. meningitidis, FITC-labelled sheep red blood cells or FITC-zymosan over time was quantified by measuring cellular fluorescence. Here, Anx-A1−/− cells exhibited a reduced uptake of all particles; in the case of opsonised sheep red blood cells for example, this was already significant by 15 min (Anx-A1+/+ 116±7 compared to 76±5 in Anx-A1−/− cells) and marked at 30 and 45 min (see Figure 1). In the case of N. meningitidis, there was a noticeable difference at 5 min (see Figure 1). Consistent with previous data, the uptake of FITC-zymosan was significantly attenuated at 10 min in the Anx-A1−/− macrophages; with the MFI values at 15 min being 806±16 compared with 371±21 for Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− cells, respectively (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Phagocytosis by Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ. Anx-A1−/− macrophages exhibit a defect in particle uptake. BMDMφ from either Anx-A1+/+ or Anx-A1−/− mice were tested for their ability to phagocytose-specific particles. Cells (5 × 105 per sample) were incubated with rhodamine green X-labelled N. meningitidis, FITC-labelled opsonised sheep red blood cells (SRBC) or zymosan (all at an MOI of 1 : 15). Samples were removed at intervals of 10–60 min, fixed and analysed by flow cytometry. The phagocytic ability of the Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ is significantly attenuated in all cases when compared with Anx-A1+/+ cells. Data are reported as the mean±s.e.m. of n=4 experiments performed in triplicate, with n=2 mice in each experiment. *P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1+/+ value.

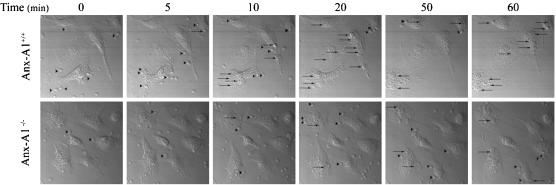

As this assay does not differentiate between cell attachment and actual ingestion of zymosan particles per se, this point was addressed by real-time confocal studies. FITC-zymosan particles were added to BMDMφ cultured on glass coverslips and incubated together at 37°C. Zymosan uptake was monitored by time-lapse microscopy over a 1 h period (a total of 239 images were captured; one every 15 s). Figure 2 illustrates that the Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ exhibited a reduced particle cell interaction compared to Anx-A1+/+ cells, resulting in decreased phagocytosis, with free particles still evident at 1 h in the medium surrounding Anx-A1−/− cells. By 30 min, Anx-A1+/+ cells had ingested nearly double the amount of zymosan particles compared to Anx-A1−/− cells (see online Supplementary video footage).

Figure 2.

Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ display a defect in FITC-zymosan uptake. BMDMφ (5 × 105 per sample) were cultured on glass coverslips mounted on a 37°C preheated microscope chamber with nonopsonised (FITC)-zymosan particles. Uptake of zymosan particles was monitored by time-lapse microscopy over a 1 h period (239 images were captured, one every 15 s). Zymosan particles, clearly visible at 0 min in both samples, have disappeared from the Anx-A1+/+ cultures by 20 min but are still visible in the Anx-A1−/− preparations at 60 min (see Supplementary video footage). Arrow heads (▸) depict zymosan cell interactions, whereas arrows (→) highlight visible phagocytosed particles. These data demonstrate that zymosan phagocytosis is grossly impaired in the Anx-A1−/− cells. The dimensions of the field represented by each individual frame are 103 × 103 μm.

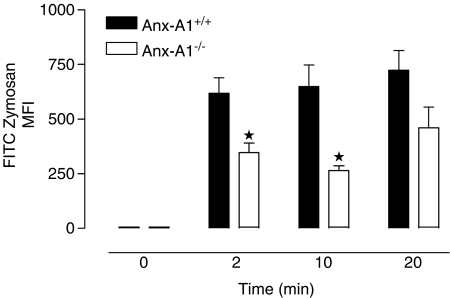

Finally, to establish whether this phenomenon was restricted to in vitro assays, animals were injected into the peritoneal cavity with FITC-zymosan (6.25 × 107 particles mouse−1), allowing resident macrophages to interact with the fluorescent particles for various periods while limiting the loss of cells by migration out of the cavity. Animals were then killed and peritoneal lavage fluids collected, fixed and the cellular fluorescence was analysed by flow cytometry. Zymosan uptake by Anx-A1−/− cells was markedly reduced at all times analysed compared to Anx-A1+/+ cells and this was noticeable already by 2 min (Anx-A1+/+ 684±103 compared to 346±45 in the Anx-A1−/− mouse; see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Clearance of FITC-labelled zymosan particles in vivo by Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− mice, following intraperitoneal injection. In vivo uptake and clearance of (FITC)-zymosan by resident macrophages in Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− mice. Animals were injected into the peritoneal cavity with 6.25 × 107 particles of zymosan (in 0.5 ml of saline) and then killed at intervals of 2–20 min. The peritoneal cavity was lavaged, the cells were recovered, fixed and subsequently analysed by flow cytometry. Zymosan uptake by resident cells in Anx-A1−/− mice was markedly reduced at all time points analysed when compared to the corresponding Anx-A1+/+ cells. Data shown are the mean±s.e.m. of n=3 mice per group. *P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1+/+ value.

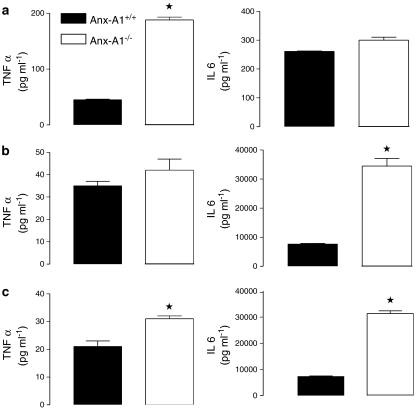

BMDMφ cytokine production

As the majority of particles are internalised in both Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− cells by 6 h, we adopted this as an appropriate time point to assess cytokine production. When incubated with zymosan particles, Anx-A1+/+ BMDMφ cells produced a typical time-dependent release of both TNFα and IL-6 (Figure 4 and Tables 2 and 3). By 4 h, incubation with zymosan or LPS 10 ng ml−1, TNFα production by Anx-A1−/− cells was significantly increased compared to the Anx-A1+/+ controls. IL-6 synthesis was also elevated throughout the entire time course. Incubation with zymosan, N. meningitidis or LPS 10 ng ml−1 for 6 h (included for comparison purposes) provoked a substantial increase in production of this cytokine (Figure 4) and Anx-A1−/− cells released significantly more IL-6 than Anx-A1+/+ cells and this was particularly evident in response to N. meningitidis or LPS as measured throughout the entire time course (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Release of TNFα and IL-6 from Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ in response to different stimuli. Left-hand panels: TNFα release from adherent BMDMφ (5 × 105) prepared from Anx-A1+/+or Anx-A1−/− mice incubated for 6 h with either (a) zymosan (MOI 1 : 50), (b) N. meningitidis (MOI 1 : 50) or (c) LPS (10 ng ml−1). At the end of the incubation period, cell-free medium was collected and TNFα assayed. Compared to Anx-A1+/+ cells, Anx-A1−/− generation of TNFα was significantly augmented during activation by each stimulus. Data are reported as TNFα concentrations in pg ml−1 and are expressed as mean±s.e.m. from n=3 experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1+/+ values. Right-hand panels: IL-6 release from adherent macrophages (5 × 105) prepared from Anx-A1+/+or Anx-A1−/− mice incubated for 6 h with either (a) zymosan (MOI 1 : 50), (b) N. meningitidis (MOI 1 : 50) or (c) LPS (10 ng ml−1). At the end of the incubation period, cell-free medium was collected and IL-6 assayed. Data are reported as IL-6 concentrations in pg ml−1 and are expressed as mean±s.e.m. from n=3 experiments performed in triplicate. *P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1+/+ values.

Table 2.

TNFα release from BMDMφ in response to different stimuli

| |

No stimulus |

Zymosan |

Neisseria |

LPS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− |

| 2 |

9.0±1.0 |

8.3±0.3 |

33±1.7 |

47.0±11.0* |

57.0±3.0 |

29.0±0.3* |

29.0±0.3 |

42.0±3.0* |

| 4 |

8.3±9.0 |

9.0±0.0 |

48.0±1.0 |

103.0±2.0* |

33.0±2.0 |

36.0±2.0 |

16.0±4.0 |

26.3±3.0 |

| 24 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±2.0 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±0.3 | 8.3±0.3 |

Adherent macrophages (0.5 × 106) prepared from Anx-A1+/+ or Anx-A1−/− mice incubated for the reported times either alone (vehicle only), with zymosan, N. meningitidis or LPS (10 ng ml−1). At the end of the incubation period, cell-free medium was collected and assayed for TNFα levels (detection limit 8.3 pg ml−1). Data reported are TNFα concentrations in pg ml−1, and are expressed as mean±s.e.m. from n=3 experiments performed in duplicate.

P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1+/+ values.

Table 3.

IL-6 release from BMDMφ in response to different stimuli

| |

No stimulus |

Zymosan |

Neisseria |

LPS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (h) | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− | Anx-A1+/+ | Anx-A1−/− |

| 2 |

213±6 |

222±6 |

230±12 |

230±8 |

243±3 |

270±17 |

250±5 |

306±14* |

| 4 |

220±3 |

216±8 |

236±3 |

246±3 |

1250±51 |

3270±303* |

1350±145 |

2867±142* |

| 24 | 226±3 | 226±3 | 252±10 | 396±28 | 38,620±2895 | 43,427±3312 | 33,620±3017 | 32,383±1158 |

Adherent macrophages (0.5 × 106) prepared from Anx-A1+/+ or Anx-A1−/− mice were incubated for the reported times either alone (vehicle only), with zymosan, N. meningitidis or LPS (10 ng ml−1). At the end of the incubation period, cell-free medium was collected and assayed for IL-6 levels. Data reported are IL-6 concentrations in pg ml−1, and are expressed as mean±s.e.m. from n=3 experiments performed in duplicate.

P<0.05 vs respective Anx-A1 +/+ values.

Anx-A1 localisation during phagocytosis

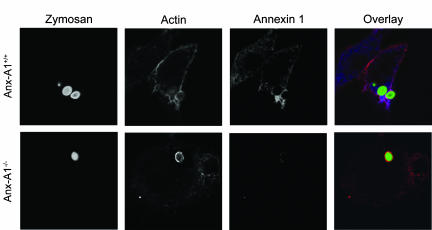

To investigate further these phagocytic defects, Anx-A1−/− BMDMφ were analysed using confocal imaging to visualise actin and Anx-A1 distribution. When FITC-zymosan particles were incubated with BMDMφ, cells adhered to glass coverslips for 5 min, both actin and Anx-A1 staining were clearly visible in the cytoplasm and the formation of the phagocytic cup was observed (see Figure 5). This occurs when actin polymerises forming microfilaments around the engulfed particle or phagosome. Cytoskeletal structural arrangements appeared to be similar in both genotypes, with an intense concentration of cytoplasmic actin around the zymosan particle during the initial stages of phagocytosis both in the presence and absence of Anx-A1. Anx-A1 cellular distribution mirrored that of actin during the initial stages of phagocytosis. These data could suggest a role for Anx-A1 during the early stages of phagocytosis.

Figure 5.

Anx-A1 and actin localisation at 5 min following zymosan phagocytosis in BMDMφ. BMDMφ of both genotypes were incubated with FITC-zymosan (green) particles for 5 min prior to the cells being fixed and permeabilised. Cells were subsequently stained for Anx-A1 (blue) and actin (red). In the Anx-A1+/+ cells, the actin cytoskeleton is clearly visible, sometimes in association with a dense network of Anx-A1. An actin cup formation may also be observed forming around the particle and this was associated with heavy Anx-A1 staining. In the Anx-A1−/− cells, no difference was observed in the formation of the actin cup, visible in both Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/−, yet only residual non-specific staining for Anx-A1 is observed in these cells. Images are representative of 10 similar images. Each individual frame represents an area of 41 × 41 μm.

Discussion

The experiments described here demonstrate that the lack of Anx-A1 is functionally related with a reduced rate of phagocytosis. Interestingly, when these cells are activated, cytokine release is exacerbated by the absence of this protein.

Researchers interested in the mechanisms and control of phagocytosis have frequently speculated on the possible role of the annexin family in these processes with some groups focussing upon an external, and others on an internal role for the protein. The earliest observations in the former category were those of Becker & Grasso (1988) who reported that dexamethasone induced the release of a protein which suppressed phagocytosis of yeast particles from elicited murine macrophages. On the basis of immunological crossreactivity, it was surmised that this was related to lipocortin 1 (the former name of Anx-A1).

Later studies in a different model system (apoptosis during mammary regression) lead McKanna (1995) to speculate that Anx-A1 had multiple roles in regulating the apoptotic event and the ensuing removal of cells by macrophages and suggested that the presence of this protein might be responsible for the lack of inflammatory changes characteristically observed during this response. The theme that Anx-A1 may play an extracellular role in regulating phagocytosis has found echoes in our own work as well as in the studies of other groups predominantly interested in apoptotic cell clearance. We have demonstrated that phagocytosis as well as a number of other leukocyte functions (such as superoxide generation) are suppressed by externally applied recombinant Anx-A1 or its mimetics (Getting et al., 1997; Goulding et al., 1998). Other groups have postulated that the caspase-induced externalisation of this protein may be important for the efficient clearing of apoptotic cells in some organisms such as Caenorhabditis elegans (Arur et al., 2003) as well as in human macrophages when phagocytosing apopototic T lymphocytes, although not thymocytes (Fan et al., 2004).

In most cases, it has been suggested that Anx-A1 acts in this way through its ability to bind to phosphatidylserine (PS), which is enriched on the cell surface during apoptotosis. However, Maderna et al. (2005) found that the Anx-A1 N-terminal peptide alone (which does not bind to PS) stimulated phagocytosis of apopototic PMN by human macrophages through a mechanism involving peptide binding to a member of the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) family, and that the initiation of apoptosis by dexamethasone was triggered by the release of immunoreactive Anx-A1. Furthermore (and congruent with our own findings here), BMDMφ from Anx-A1−/− mice exhibited a greatly reduced capacity to phagocytose PMN when compared to their wild-type counterparts.

In the present study, confocal and flow cytometry analysis clearly demonstrate that the Anx-A1−/− cells exhibit reduced phagocytosis when bacteria and fungal particles are used as targets and that this is not related to an obvious cytoskeletal defect. Interestingly, we observed the Anx-A1 recruitment and colocalisation with polymerised actin around the phagocytic cup within a few minutes of particle ingestion in Anx-A1+/+ cells. These data are in agreement with the published literature; many annexins have been shown to translocate to the surface of phagosomes during phagocytosis in cell lines (Ernst, 1991; Harricane et al., 1996; Collins et al., 1997; Diakonova et al., 1997; Larsson et al., 1997; Sjolin et al., 1997; Majeed et al., 1998; Pittis & Garcia, 1999; Kusumawati et al., 2000; 2001). Interestingly, Anx-A1 location varies with the nature of the phagocytic target. In J774 macrophages, phagocytosis of latex beads triggered Anx-A1 association with phagosomes and early endosomes (as well as with the plasma membrane, with F-actin at the site of membrane protrusions) but Anx-A4 seemed to be more associated with older phagosomes and Anx-A5 on late endocytic organelles. When Brucella suis was used as a phagocytic target in this cell line, targeting of Anx-A1 to the phagosome was not seen when Anx-A1 is mutated from Ser27 to Glu into the cells implying that phosphorylation at this residue is important in controlling this association (Kusumawati et al., 2000; 2001). In U937 cells, Anx-A1 translocated to phagosomes containing dead, but not live B. suis organisms (Harricane et al., 1996).

It is tempting to speculate that the association of members of the annexin family with subcellular organelles such as phagosomes is simply mediated through their ability to bind to membranes in a calcium-dependent fashion, but the totality of the published data taken together suggests that this is not the case. The fact that there are clear differences in the distribution of the family depending upon the nature of the stimulus, and whether it is viable or killed, suggests that these proteins subserve a more subtle role, perhaps as regulators of the initial signalling process that follows the interaction of the organism with the phagocytic cell itself. In the case of Anx-A1, this role is seemingly dependent upon an intact Ser27 residue, located in the unique N-terminal region of the molecule and not in the core domain containing the calcium-binding motifs, providing further evidence for specificity of action.

Data from our flow cytometry analysis performed in this study is worthy for discussion. Both Anx-A1+/+ and Anx-A1−/− cells displayed similar levels of membrane FcRγII/III and F4/80 proteins. However, CD11b expression is markedly reduced (∼25%) in the Anx-A1−/− cells compared to Anx-A1+/+ cells, this α-subunit of the β2-integrin family may be responsible for the integrity of membrane protrusions around the loosely attached particles to facilitate their ingestion into the phagosome. It is not known how intracellular Anx-A1 regulates CD11b gene expression, or whether this is a direct effect or through post-transcriptional events. However, glucocorticoids are known to reduce CD11b expression on circulating and resident granulocytes and monocytes (Burton et al., 1995; Das et al., 1997; Lim et al., 2000), in a cycloheximide-sensitive manner (Filep et al., 1997).

Finally, the enhanced cytokine release of TNFα and IL-6 seen here by Anx-A1−/− cells following incubation with either zymosan, N. meningitidis or LPS is congruent with previous studies during acute and chronic inflammation (Hannon et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2004). Several other studies have illustrated during the acute inflammatory response recombinant Anx-A1 or its mimetic to be potent inhibitors of cytokine synthesis (Sudlow et al., 1996). This phenomenon was also observed during zymosan peritonitis in the Anx-A1−/− mouse, with a significantly amplified synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines resulting in an amplified influx of neutrophils (Hannon et al., 2003). This suggests that although phagocytic dynamics are grossly impaired in these cells, downstream signalling is, if anything, considerably augmented. Interestingly, cytochalasin D, which inhibits actin polymerisation and therefore phagocytosis, does not inhibit the release of TNFα, demonstrating that the process of particle ingestion is separate from the signal transduction steps leading to enhanced cytokine synthesis and release (Brown et al., 2003). The exact mechanism by which the lack of Anx-A1 results in this enhanced cytokine production is not completely understood but a likely explanation emerging from recent studies is the absence of an important negative feedback loop, autocrine stimulation by Anx-A1 of the FPR receptor family in these cells. Although the intracellular signalling pathways have yet to be completely elucidated, substantial experimental evidence now supports the involvement of this receptor family in the transduction of signals from extracellular Anx-A1 (Perretti et al., 2001; Gavins et al., 2003; Ernst et al., 2004; Hayhoe et al., 2006). Lipoxin A4, another ligand that acts through members of the same receptor family (FPRL1; ALXR) or its stable analogues, has been shown to inhibit the production of IL-1β in rat mesangial cells (Wu et al., 2005) and human PMN (Hachicha et al., 1999; Pouliot & Serhan, 1999) by TNFα stimulation and enhances the production of anti-inflammatory TGF-β in inflammatory exudates (Bannenberg et al., 2005). Lipoxin agonists at the same receptor also inhibit IL-1β-induced release of IL-6, and IL-8 from human synovial fibroblasts (Sodin-Semrl et al., 2000) and block Salmonella typhimurium induced in IL-8 from intestinal epithelial cells without effecting the adherence or phagocytosis of the organism (Gewirtz et al., 1998). It therefore seems probable that the same situation obtains in our experimental system here in that the absence of Anx-A1 leads to an increased release of cytokines.

It is possible that future work might reconcile the function of nuclear Anx-A1 localisation with a function on nuclear gene transcription such as been suggested by Wang et al. (2004), but in any case the augmented production of several inflammatory cytokines is a common feature in Anx-A1−/− cells and this has been associated with a reduction of the inhibitory effects of glucocorticoids and the abnormally activated signal transduction pathways (Wu et al., 1995; Croxtall et al., 2003).

External data objects

Acknowledgments

R.J.F. is a Principal Fellow of the Wellcome Trust; M.P. is a Senior Research Fellow of the Arthritis Research Campaign and S.Y. held a Ph.D. studentship from the Nuffield Foundation, U.K. We thank the Wellcome Trust (Grant no. 051887/97) and the Oliver Bird Fund (Project RHE/00057/G) for supporting this study.

Abbreviations

- ALXR

lipoxin A4 receptor

- Anx-A1

annexin A1

- BMD

bone marrow culture derived

- FPR

formylpeptide receptor

- FPRL1

FPR like1

- IL-6

interleukin 6

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- Mϕ

macrophage

- PMN

polymorphonuclear leukocyte

- TNFα

tumour necrosis factor α

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on British Journal of Pharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/bjp)

References

- ARUR S., UCHE U.E., REZAUL K., FONG M., SCRANTON V., COWAN A.E., MOHLER W., HAN D.K. Annexin I is an endogenous ligand that mediates apoptotic cell engulfment. Dev. Cell. 2003;4:587–598. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00090-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BANNENBERG G.L., CHIANG N., ARIEL A., ARITA M., TJONAHEN E., GOTLINGER K.H., HONG S., SERHAN C.N. Molecular circuits of resolution: formation and actions of resolvins and protectins. J. Immunol. 2005;174:4345–4355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKER J., GRASSO R.J. Suppression of yeast ingestion by dexamethasone in macrophage cultures: evidence for a steroid-induced phagocytosis inhibitory protein. Int. J. Immunopharmacol. 1988;10:325–338. doi: 10.1016/0192-0561(88)90118-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BECKER J.L., GRASSO R.J., DAVIS J.S. Dexamethasone action inhibits the release of arachidonic acid from phosphatidylcholine during the suppression of yeast phagocytosis in macrophage cultures. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1988;153:583–590. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(88)81135-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRAY M.A., GORDON D. Prostaglandin production by macrophages and the effect of anti-inflammatory drugs. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1978;63:635–642. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1978.tb17276.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN G.D., HERRE J., WILLIAMS D.L., WILLMENT J.A., MARSHALL A.S., GORDON S. Dectin-1 mediates the biological effects of beta-glucans. J. Exp. Med. 2003;197:1119–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BURTON J.L., KEHRLI M.E., Jr, KAPIL S., HORST R.L. Regulation of L-selectin and CD18 on bovine neutrophils by glucocorticoids: effects of cortisol and dexamethasone. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995;57:317–325. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COLLINS H.L., SCHAIBLE U.E., ERNST J.D., RUSSELL D.G. Transfer of phagocytosed particles to the parasitophorous vacuole of Leishmania mexicana is a transient phenomenon preceding the acquisition of annexin I by the phagosome. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110 (Part 2):191–200. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COMERA C., RUSSO-MARIE F. Glucocorticoid-induced annexin 1 secretion by monocytes and peritoneal leukocytes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;115:1043–1047. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CROXTALL J.D., GILROY D.W., SOLITO E., CHOUDHURY Q., WARD B.J., BUCKINGHAM J.C., FLOWER R.J. Attenuation of glucocorticoid functions in an Anx-A1−/− cell line. Biochem. J. 2003;371:927–935. doi: 10.1042/BJ20021856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DAS A.M., FLOWER R.J., HELLEWELL P.G., TEIXEIRA M.M., PERRETTI M. A novel murine model of allergic inflammation to study the effect of dexamethasone on eosinophil recruitment. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;121:97–104. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DIAKONOVA M., GERKE V., ERNST J., LIAUTARD J.P., VAN DER VUSSE G., GRIFFITHS G. Localization of five annexins in J774 macrophages and on isolated phagosomes. J. Cell Sci. 1997;110:1199–1213. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.10.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DREVETS D.A., CAMPBELL P.A. Macrophage phagocytosis: use of fluorescence microscopy to distinguish between extracellular and intracellular bacteria. J. Immunol. Methods. 1991;142:31–38. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(91)90289-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNST J.D. Annexin III translocates to the periphagosomal region when neutrophils ingest opsonized yeast. J. Immunol. 1991;146:3110–3114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ERNST S., LANGE C., WILBERS A., GOEBELER V., GERKE V., RESCHER U. An annexin 1 N-terminal peptide activates leukocytes by triggering different members of the formyl peptide receptor family. J. Immunol. 2004;172:7669–7676. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAN X., KRAHLING S., SMITH D., WILLIAMSON P., SCHLEGEL R.A. Macrophage surface expression of annexins I and II in the phagocytosis of apoptotic lymphocytes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2004;15:2863–2872. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-09-0670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FILEP J.G., DELALANDRE A., PAYETTE Y., FOLDES-FILEP E. Glucocorticoid receptor regulates expression of L-selectin and CD11/CD18 on human neutrophils. Circulation. 1997;96:295–301. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.1.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAVINS F.N., YONA S., KAMAL A.M., FLOWER R.J., PERRETTI M. Leukocyte antiadhesive actions of annexin 1: ALXR- and FPR-related anti-inflammatory mechanisms. Blood. 2003;101:4140–4147. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GERKE V., MOSS S.E. Annexins: from structure to function. Physiol. Rev. 2002;82:331–371. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GETTING S.J. Melanocortin peptides and their receptors: new targets for anti-inflammatory therapy. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2002;23:447–449. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(02)02103-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GETTING S.J., FLOWER R.J., PERRETTI M. Inhibition of neutrophil and monocyte recruitment by endogenous and exogenous lipocortin 1. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1997;120:1075–1082. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GEWIRTZ A.T., MCCORMICK B., NEISH A.S., PETASIS N.A., GRONERT K., SERHAN C.N., MADARA J.L. Pathogen-induced chemokine secretion from model intestinal epithelium is inhibited by lipoxin A4 analogs. J. Clin. Invest. 1998;101:1860–1869. doi: 10.1172/JCI1339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GIAIMIS J., LOMBARD Y., POINDRON P., MULLER C.D. Flow cytometry distinction between adherent and phagocytized yeast particles. Cytometry. 1994;17:173–178. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990170210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOULDING N.J. The molecular complexity of glucocorticoid actions in inflammation – a four-ring circus. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2004;4:629–636. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2004.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GOULDING N.J., EUZGER H.S., BUTT S.K., PERRETTI M. Novel pathways for glucocorticoid effects on neutrophils in chronic inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 1998;47 (Suppl. 3):S158–S165. doi: 10.1007/s000110050310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HACHICHA M., POULIOT M., PETASIS N.A., SERHAN C.N. Lipoxin (LX)A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-LXA4 inhibit tumor necrosis factor 1alpha-initiated neutrophil responses and trafficking: regulators of a cytokine-chemokine axis. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1923–1930. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.12.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANNON R., CROXTALL J.D., GETTING S.J., ROVIEZZO F., YONA S., PAUL-CLARK M.J., GAVINS F.N., PERRETTI M., MORRIS J.F., BUCKINGHAM J.C., FLOWER R.J. Aberrant inflammation and resistance to glucocorticoids in annexin 1−/− mouse. FASEB J. 2003;17:253–255. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0239fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRICANE M.C., CARON E., PORTE F., LIAUTARD J.P. Distribution of annexin I during non-pathogen or pathogen phagocytosis by confocal imaging and immunogold electron microscopy. Cell. Biol. Int. 1996;20:193–203. doi: 10.1006/cbir.1996.0024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYHOE R.P., KAMAL A.M., SOLITO E., FLOWER R.J., COOPER D., PERRETTI M. Annexin 1 and its bioactive peptide inhibit neutrophil–endothelium interactions under flow indication of distinct receptor involvement. Blood. 2006;107:2123–2130. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSUMAWATI A., CAZEVIEILLE C., PORTE F., BETTACHE S., LIAUTARD J.P., SRI WIDADA J. Early events and implication of F-actin and annexin I associated structures in the phagocytic uptake of Brucella suis by the J-774A.1 murine cell line and human monocytes. Microb. Pathog. 2000;28:343–352. doi: 10.1006/mpat.2000.0354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KUSUMAWATI A., LIAUTARD J.P., SRI WIDADA J. Implication of annexin 1 in phagocytosis: effects of n-terminal domain deletions and point mutations of the phosphorylation site Ser-27. Cell. Biol. Int. 2001;25:809–813. doi: 10.1006/cbir.2000.0704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LARSSON M., MAJEED M., ERNST J.D., MAGNUSSON K.E., STENDAHL O., FORSUM U. Role of annexins in endocytosis of antigens in immature human dendritic cells. Immunology. 1997;92:501–511. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIM L.H., FLOWER R.J., PERRETTI M., DAS A.M. Glucocorticoid receptor activation reduces CD11b and CD49d levels on murine eosinophils: characterization and functional relevance. Am. J. Resp. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2000;22:693–701. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.22.6.3890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MADERNA P., YONA S., PERRETTI M., GODSON C. Modulation of phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by supernatant from dexamethasone-treated macrophages and annexin-derived peptide Ac(2–26) J. Immunol. 2005;174:3727–3733. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.6.3727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAJEED M., PERSKVIST N., ERNST J.D., ORSELIUS K., STENDAHL O. Roles of calcium and annexins in phagocytosis and elimination of an attenuated strain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human neutrophils. Microb. Pathog. 1998;24:309–320. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1997.0200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARIDONNEAU-PARINI I., ERRASFA M., RUSSO-MARIE F. Inhibition of O2-generation by dexamethasone is mimicked by lipocortin I in alveolar macrophages. J. Clin. Invest. 1989;83:1936–1940. doi: 10.1172/JCI114101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MCKANNA J.A. Lipocortin 1 in apoptosis: mammary regression. Anat. Rec. 1995;242:1–10. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092420102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERRETTI M. Lipocortin 1 and chemokine modulation of granulocyte and monocyte accumulation in experimental inflammation. Gen. Pharmacol. 1998;31:545–552. doi: 10.1016/s0306-3623(98)00039-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PERRETTI M., GETTING S.J., SOLITO E., MURPHY P.M., GAO J.L. Involvement of the receptor for formylated peptides in the in vivo anti-migratory actions of annexin 1 and its mimetics. Am. J. Pathol. 2001;158:1969–1973. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64667-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PITTIS M.G., GARCIA R.C. Annexins VII and XI are present in a human macrophage-like cell line. Differential translocation on FcR-mediated phagocytosis. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1999;66:845–850. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- POULIOT M., SERHAN C.N. Lipoxin A4 and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-LXA4 inhibit tumor necrosis factor-alpha-initiated neutrophil responses and trafficking: novel regulators of a cytokine-chemokine axis relevant to periodontal diseases. J. Periodontal Res. 1999;34:370–373. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02268.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SJOLIN C., MOVITZ C., LUNDQVIST H., DAHLGREN C. Translocation of annexin XI to neutrophil subcellular organelles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1326:149–156. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SODIN-SEMRL S., TADDEO B., TSENG D., VARGA J., FIORE S. Lipoxin A4 inhibits IL-1 beta-induced IL-6, IL-8, and matrix metalloproteinase-3 production in human synovial fibroblasts and enhances synthesis of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases. J. Immunol. 2000;164:2660–2666. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUDLOW A.W., CAREY F., FORDER R., ROTHWELL N.J. The role of lipocortin-1 in dexamethasone-induced suppression of PGE2 and TNF alpha release from human peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;117:1449–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15305.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG J.L., GRAY R.M., HAUDEK K.C., PATTERSON R.J. Nucleocytoplasmic lectins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2004;1673:75–93. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU C.C., CROXTALL J.D., PERRETTI M., BRYANT C.E., THIEMERMANN C., FLOWER R.J., VANE J.R. Lipocortin 1 mediates the inhibition by dexamethasone of the induction by endotoxin of nitric oxide synthase in the rat. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:3473–3477. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.8.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WU S.H., LU C., DONG L., ZHOU G.P., HE Z.G., CHEN Z.Q. Lipoxin A4 inhibits TNF-alpha-induced production of interleukins and proliferation of rat mesangial cells. Kidney. Int. 2005;68:35–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00379.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG Y.H., MORAND E.F., GETTING S.J., PAUL-CLARK M., LIU D.L., YONA S., HANNON R., BUCKINGHAM J.C., PERRETTI M., FLOWER R.J. Modulation of inflammation and response to dexamethasone by Annexin 1 in antigen-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:976–984. doi: 10.1002/art.20201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YONA S., BUCKINGHAM J.C., PERRETTI M., FLOWER R.J. Stimulus-specific defect in the phagocytic pathways of annexin 1 null macrophages. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2004;142:90–98. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YONA S., WARD B., BUCKINGHAM J.C., PERRETTI M., FLOWER R.J. Macrophage biology in the Anx-A1−/− mouse. Prostag Leukotr. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2005;72:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.