Abstract

Macrophage activation is a key feature of inflammatory reactions occurring during bacterial infections, immune responses and tissue injury. We previously demonstrated that human macrophages of different origin express the tyrosine kinase receptor recepteur d'origine nantaise, the human receptor for MSP (RON) and produce superoxide anion (O2−) when challenged with macrophage-stimulating protein (MSP), the endogenous ligand for RON.

This study was aimed to evaluate the role of MSP in alveolar macrophages (AM) isolated from healthy volunteers and patients with interstitial lung diseases (sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis), either smokers or non-smokers, by evaluating the respiratory burst, cytokine release and nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) activation. MSP effects were compared with those induced by known AM stimuli, for example, phorbol myristate acetate, N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine, lipopolysaccharide.

MSP evokes O2− production, cytokine release and NF-κB activation in a concentration-dependent manner. By evaluating the respiratory burst, we demonstrate a significantly increased O2− production in AM from healthy smokers or smokers with pulmonary fibrosis, as compared to non-smokers, thus suggesting MSP as an enhancer of cigarette smoke toxicity.

Besides inducing interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) production, MSP triggers an enhanced tumor necrosis factor-alpha release, especially in healthy and pulmonary fibrosis smokers. On the contrary, MSP-induced IL-10 release is higher in AM from healthy non-smokers.

MSP activates the transcription factor NF-κB; this effect is more potent in healthy and fibrosis smokers (2.5-fold increase in p50 subunit translocation). This effect is receptor-mediated, as it is prevented by a monoclonal anti-human MSP antibody.

The higher effectiveness of MSP in AM from healthy smokers and patients with pulmonary fibrosis is suggestive of its role in these clinical conditions.

Keywords: Macrophage-stimulating protein, human alveolar macrophages, tobacco smoke, NF-κB activation, respiratory burst, cytokine release, sarcoidosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, p50 subunit, IL-10, TNF-α

Introduction

Macrophage-stimulating protein (MSP) is a 80-kDa serum protein that was identified about 30 years ago by its ability to stimulate shape change, migration and phagocytosis of murine resident peritoneal macrophages (Leonard & Skeel, 1976). MSP is synthesized in the liver and circulates in the blood at a serum concentration of 2–5 mM as an inactive precursor, pro-MSP. The bioactive MSP is produced by proteolytic conversion during blood coagulation and at sites of inflammation (Wang et al., 2002). MSP acts on target tissues by activating the tyrosine kinase receptors recepteur d'origine nantaise (RON), the human receptor for MSP, and stem cell-derived tyrosine kinase (STK), the murine receptor for MSP, the expression of STK being regarded as a marker of terminal differentiation of murine macrophages (Iwama et al., 1995). MSP has been shown to inhibit lipopolysaccharide (LPS)- and cytokine-induced nitric oxide (NO) production as well as inducible NO synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase-2 expression in mouse peritoneal macrophages (Chen et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2002; Zhou et al., 2002). Targeted deletion of STK resulted in enhanced NO production by murine macrophages (Correll et al., 1997) and the MSP/STK complex reduced the nuclear translocation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) induced by LPS plus IFN-γ in STK-transfected RAW 264.7 cells (a murine macrophage cell line) (Liu et al., 1999). As known, human macrophages present marked differences from murine peritoneal macrophages and macrophage cell lines, especially regarding NO production: while murine macrophages rapidly produce large amounts of NO after challenge with inflammatory cytokines or LPS, human macrophages usually do not, although they express the iNOS gene (Albina, 1995).

The effects of MSP on human macrophages and its role in human pathophysiology have been poorly investigated. In 2001, we originally demonstrated that human macrophages of different origin (peritoneal macrophages isolated from ascitic fluid of cirrhotic patients, alveolar macrophages (AM) from eight patients with different lung diseases, as well as monocyte-derived macrophages from healthy volunteers), but not human monocytes, express authentic and functional RON receptors and undergo a respiratory burst upon challenge with MSP (Brunelleschi et al., 2001). MSP-evoked superoxide anion (O2−) production is mediated by tyrosine kinase activity, requires the activation of Src, but not of phosphatidyl-inositol 3-kinase (which is implicated in MSP/RON signal transduction in other cell types) and involves MAP kinase and p38 signalling pathways (Brunelleschi et al., 2001).

Other authors also reported that MSP is present, at biological significant concentrations, in the broncho-alveolar spaces, where AM are located, as well as in induced sputum from healthy subjects and patients with bronchiectasis (Sakamoto et al., 1997; Takano et al., 2000).

The present study was undertaken to explore the role of MSP in different lung diseases, by evaluating the respiratory burst, cytokine release and NF-κB signalling in AM isolated from healthy volunteers and patients with interstitial lung diseases, for example, sarcoidosis and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), either smokers or non-smokers.

We demonstrate that, in a concentration-dependent manner, MSP evokes O2− production and cytokine release, being more effective in healthy smokers and in patients with IPF. We also present direct evidence that MSP activates the transcription factor NF-κB, the p50 subunit being especially involved, so providing new insights on the possible mechanisms involved in the control of AM responsiveness.

Methods

Isolation of human AM from broncho-alveolar lavage

This study and the research protocol were approved by the local Ethical Committee. Broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) was mainly performed for diagnostic purposes, to have a further validation/confirmation of the suspected disease. AM were isolated from BAL as described (Brunelleschi et al., 2001; Bardelli et al., 2005). After informed consent and pretreatment with parenteral atropine sulphate, airways were anaesthetized and a fiberoptic bronchoscope was advanced and wedged into the middle lobe under direct visualization. Lavage was carried out with 140–200 ml of prewarmed (37°C) sterile saline solution in 20-ml aliquots with immediate gentle vacuum (syringe) aspiration after each injection. The fluid obtained was filtered through two layers of sterile surgical gauze and centrifuged (400 × g, 30 min). The whole BAL pellet was washed twice in phosphate-buffered salt solution (PBS), resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 2 mM glutamine, 10 mM Hepes, 50 μg ml−1 streptomycin and 5 U ml−1 penicillin, and plated in six-well tissue culture plates (Costar, U.K.). After 2 h at 37°C in humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere, nonadherent cells (mainly lymphocytes) were gently removed and AM were used for the experiments. Total cell count and viability evaluation (Trypan blue dye exclusion test, always >98%) were performed on a Burker haemocytometer. Differential cell count was carried out on Diff-Quick (Don Baxter)-stained cytospin smears, counting at least 400 cells. The adherent cell population was >99% AM. Phenotypical analysis was carried out on cytocentrifuge (Cytospin, U.K.; 500 r.p.m., 10 min) slides by employing leukocyte-specific monoclonal antibodies for CD68, CD14 and HLA-DR (from Becton Dickinson, U.K.). In some cases, monocyte-derived macrophages (MDM) were prepared from circulating monocytes of single individual patients, cultured for 7–8 days in a CO2 incubator at 37°C in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FCS, glutamine and antibiotics, as described (Brunelleschi et al., 2001). MDM were defined as macrophage-like cells also by evaluating the decrease in the surface monocyte marker CD14 (Brunelleschi et al., 2001).

Superoxide anion (O2−) production in AM

Adherent AM (0.4–1 × 106 cells/plate) were washed twice with PBS, incubated in RPMI 1640 medium (without phenol red, no antibiotics and no FCS) and challenged with increasing concentrations of MSP (3–500 ng ml−1) for 30 min. The effects of MSP were compared with those evoked by maximal effective concentrations of the protein kinase C activator, phorbol 12-myristate acetate (PMA; 10−7 M) and the bacterial peptide, N-formyl-methyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (FMLP; 10−6 M). O2− production, evaluated by the superoxide dismutase (SOD)-inhibitable cytochrome C reduction, was expressed as nmol cytochrome C reduced 106 cells−1 30 min−1, using an extinction coefficient of 21.1 mM (Brunelleschi et al., 2001). To avoid interference with spectrophotometrical recordings of O2− production, AM were incubated with RPMI 1640 without phenol red. Experiments were performed in duplicate; control values (e.g., basal O2− production in the absence of stimuli) were subtracted from all determinations.

Cytokine release in AM

Adherent AM were challenged with MSP (3–500 ng ml−1) or the standard stimuli (PMA 10−7 M, FMLP 10−6 M, LPS 10 ng ml−1) for 24 h at 37°C to ensure maximal cytokine release (Bardelli et al., 2005). Supernatants were collected and stored at −20°C. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin 1 beta (IL-1β) and interleukin-10 (IL-10) (the latter was evaluated as the most important anti-inflammatory cytokine) in the samples were measured using enzyme-linked immunoassay kit (Pelikine Compact™ human ELISA kit). The measurements were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The minimum detectable concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10 were 1.4, 1.5 and 1.3 pg ml−1, respectively. No crossreactivity was observed with any other known cytokine. Control values (e.g., cytokine release from untreated, unstimulated AM) were subtracted from all determinations. Results are expressed in pg ml−1.

Evaluation of NF-κB activation

The activation of NF-κB induced by MSP, PMA and LPS was evaluated by measuring the nuclear migration (by electrophoretic mobility shift assay, EMSA) as well as the nuclear content of p50 and p65 subunits (by ELISA), as previously described (Bardelli et al., 2005). As EMSA assays require large numbers of cells (5–10 × 106 for each sample) to perform these experiments, we used MDM obtained from the same individuals who underwent BAL procedure. In EMSA assays, nuclear extracts (5 μg) from MDM were incubated with 2 μg poly (dI-dC) and [32P]ATP-labelled oligonucleotide probe (100,000–150,000 c.p.m.; Promega, St Louis, U.S.A.) in binding buffer for 30 min at room temperature. The NF-κB consensus oligonucleotide (5′-AGTTGAGGGGACTTTCCCAGGC-3′) was from Promega. The nucleotide–protein complex was separated on a polyacrylamide gel, the gel was dried and radioactive bands were detected by autoradiography (Bardelli et al., 2005). Supershift assays were performed with commercial antibodies (anti-NF-κB p50: ab 7949 and anti-NF-κB p65: ab 7970) from Abcam (U.K.) at a final concentration of 1 μg ml−1. AM nuclear extracts were prepared and evaluated for the presence of p50 and p65/RelA subunits using Trans AM™ NF-κB p50 Chemi and NF-κB p65 Chemi Transcription Factor Assay kits (Active Motif Europe, Belgium), according to the manufacturer's instructions: an equal amount (1 μg) of lysate was used for each sample. These assay kits specifically detected bound NF-κB p65 or p50 subunits in human extracts; activities of p50 and p65 were measured by a Rosys Anthos Lucy 1 luminometer and results are expressed as RLU (Relative Luminescence Unit), according to Bardelli et al. (2005).

Drugs and analytical reagents

Human recombinant MSP and anti-human MSP β-chain monoclonal antibody (MAB 735) were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, U.S.A.); FCS (Lot 40F-7234K) was from Gibco (Paisley, U.K.). PBS, RPMI 1640 (with or without phenol red), BSA, glutamine, Hepes, streptomycin, penicillin, LPS, PMA, SOD, cytochrome c, bromophenol blue, glycine, glycerol, methanol and Tween 20 were obtained from Sigma (Milwaukee, U.S.A.). Nitro-cellulose filters (Hybond) and poly(dI-dC) were from Amersham (Buckinghamshire, U.K.). All the reagents for EMSA assays were purchased from Promega Corporation (St Louis, U.S.A.). Tissue-culture plates were from Costar Ltd (Buckinghamshire, U.K.); all cell culture reagents, with the exception of FCS, were endotoxin-free according to details provided by the manufacturer. TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-10 immunoassay kits were obtained from CLB/Sanquin, Central Laboratory of the Netherlands Red Cross (Netherlands).

Data and statistical analysis

Data are mean±s.e.m. of duplicate determinations of ‘n' independent experiments. Concentration–response curves for MSP were constructed and EC50 values were interpolated from curves of best-fit. When required, statistical evaluation was performed by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test.

Results

Study population, BAL and phenotype of AM

A total of 47 subjects, 25 male and 22 female subjects, aged between 45 and 68 years, 23 smokers and 24 non-smokers, were studied; 15 patients had pulmonary sarcoidosis, 14 patients had IPF and 18 individuals were classified as healthy subjects, that is, individuals with no history of cardiopulmonary disease or other chronic diseases, no diagnosed lung disease and no medication. In a few cases, the attribution of an ‘healthy' subject to the category was done after the BAL procedure. The characteristics and smoking history of the study population are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study population

| Subjects | Sex (M/F) | Age (years) | Number of cigarettes day−1 | Years on smoke |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthy |

|

|

|

|

| Smokers (n=10) |

6/4 |

51.4±1.6 |

20.3±2 |

23.4±2.5 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

4/4 |

54.3±2.7 |

— |

— |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Sarcoidosis | ||||

| Smokers (n=7) |

4/3 |

55.3±2.2 |

18.3±2.3 |

25.4±2.7 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

3/5 |

53.4±2.4 |

— |

— |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

Pulmonary fibrosis | ||||

| Smokers (n=6) |

3/3 |

52.8±2 |

19.7±3 |

25.3±3 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) | 5/3 | 53.8±1.5 | — | — |

Total and differential cell counts in BAL and phenotype of AM are presented in Table 2. As expected, a significant (P<0.05) increase in the total cell number was observed in all the smoker subjects as compared to non-smokers; patients with sarcoidosis (both smokers and non-smokers) presented an alveolar lymphocytosis (25±2 and 24±2%, respectively) and a reduction in AM percentage (74.2±1.4% in smokers and 74.6±3% in non-smokers) (Table 2). The great majority of AM (96±1%) in healthy smokers was CD68+ and a high percentage (84±1 and 68±3%, respectively) of AM expressed also HLA-DR and CD14. As known, CD68 expression is related to the presence of AM involved in the oxidative burst, CD14 expression is related to cytokine production by LPS, whereas HLA-DR is related to antigen presentation. The expression CD14 and CD68 was significantly (P<0.05) higher in AM collected from healthy smokers and smoker patients as compared to the respective non-smoker groups (Table 2). The non-smoker sarcoidosis group presented a very low (26±2.5%; n=8) CD14 expression as compared to sarcoidosis smokers (55±2%; n=7); similar results were obtained in the IPF group (Table 2). HLA-DR expression presented only minor variations among groups (values around 70–80% being always measured), with the only exception of the non-smoker IPF patients who presented a significant reduced HLA-DR expression (71±2; n=8) as compared to the IPF smokers (82±1%; n=6) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Total and differential cell count in BAL and AM phenotype

| Subjects | Total cell ml−1 BAL | AM (%) | Lympho (%) | PMN (%) | CD68+(%) | HLA-DR+(%) | CD14+(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthy |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smokers (n=10) |

390.600±6.000 |

91.4±1.9 |

8.2±2 |

1±0.5 |

96±1 |

84±1 |

68±3 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

138.000±5.000* |

90.6±1 |

8.6±1 |

0.2±0.1 |

83±1* |

86±1 |

51±1* |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sarcoidosis | |||||||

| Smokers (n=7) |

348.000±6.200 |

74.2±1.4 |

25±2 |

1±0.5 |

91±0.4 |

77±3 |

55±2 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

170.000±6.900* |

74.6±3 |

24±2 |

1±0.5 |

82±0.2* |

72±4 |

26±2.5* |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pulmonary fibrosis | |||||||

| Smokers (n=6) |

380.500±6.000 |

86±3 |

12±4 |

1±0.3 |

93±0.8 |

82±1 |

58±3 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) | 202.000±5.500* | 82±5 | 13±3 | 3±1.2 | 85±0.5* | 71±2* | 32±3* |

Data are given as total cell number ml−1 BAL and percentage of total cell population (differential) in BAL. AM=alveolar macrophages; Lympho=alveolar lymphocytes; PMN=alveolar neutrophils. The AM phenotype was evaluated by measuring CD68, CD14 and HLA-DR; positive cells are expressed as percentage of total AM.

Denotes P<0.05 vs smokers of the corresponding group.

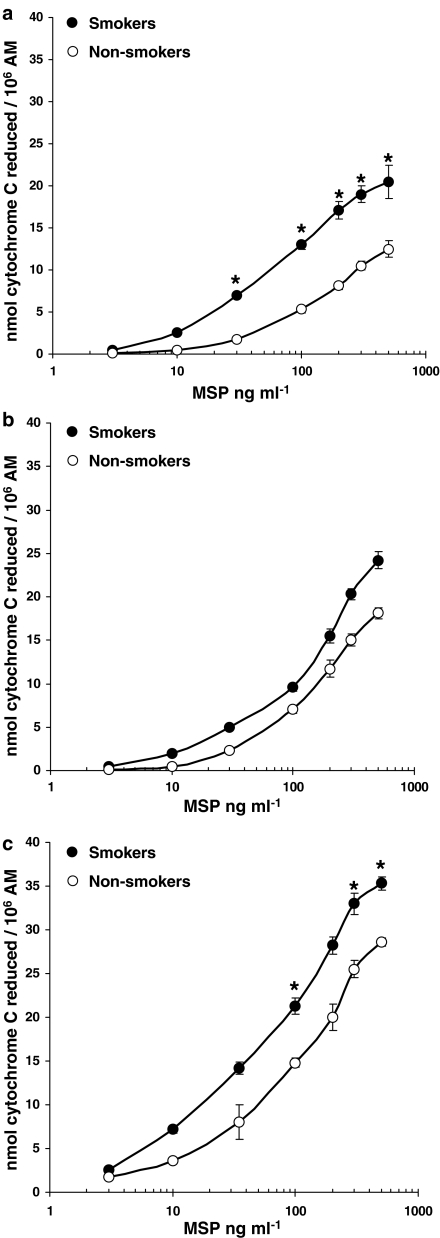

MSP evokes O2− production in human AM

Control, unstimulated human AM from healthy subjects (smokers and non-smokers) and patients with interstitial lung diseases (both smokers and non-smokers) spontaneously released substantial amounts of O2−, as reported in Table 3. These values were subtracted from those obtained after MSP, FMLP or PMA challenge to obtain the net O2− production. PMA, used at 10−7 M (a near maximal concentration), produced 23±2 (n=10) and 17±1.5 (n=8; P<0.05) nmol cytochrome c reduced per 106 AM in healthy smokers and non-smokers, respectively (Table 3) and even higher amounts in AM isolated from patients with interstitial lung diseases, the maximal effect (38±2.2 nmol cytochrome c reduced 106 AM−1; n=6) being observed in smoker patients with IPF (Table 3). FMLP, used at the fully effective 10−6 M concentration, was less potent than PMA; in this case, too, maximal O2− production was observed in smoker patients with IPF (Table 3). On the contrary, LPS-evoked O2− production was minimal (data not shown). In the concentration range 3–500 ng ml−1, MSP evoked O2− production in AM from both smokers and non-smokers, higher production being observed in smokers (Figure 1). As depicted in Figure 1, maximal activation by MSP was observed at 300–500 ng ml−1, MSP being particularly effective in healthy smokers (P<0.05 vs non-smokers; Figure 1a) and in patients with IPF (Figure 1c). In AM from sarcoidosis patients, MSP, although effective, did not demonstrate significant differences between smokers and non-smokers (Figure 1b). In all cases, MSP-induced maximal O2− production was quantitatively similar to the PMA-evoked one (Figure 1 and Table 3). The EC50 values for MSP were: 55 ng ml−1 in healthy smokers and 103 ng ml−1 in healthy non-smokers, 100 and 118 ng ml−1 in sarcoidosis patients (smokers and non-smokers, respectively), 35 ng ml−1 in smokers with IPF and 65 ng ml−1 in non-smokers with IPF (Figure 1 a–c).

Table 3.

Superoxide anion production from AM

| Subjects | O2− production, control | O2− production, PMA 10−7 M | O2− production, FMLP 10−6 M |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthy | |||

| Smokers (n=10) |

13.1±2 |

23±2 |

9.5±1.2 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

2.2±0.5** |

17±1.5* |

3.5±0.6* |

| |

|

|

|

|

Sarcoidosis | |||

| Smokers (n=7) |

9±1 |

30±2 |

8±2 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) |

4±0.8* |

24±1.8* |

7.2±1.8 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Pulmonary Fibrosis | |||

| Smokers (n=6) |

8.2±1.2 |

38±2.2 |

18.2±3 |

| Non-smokers (n=8) | 4.4±1.8* | 30±2 | 16±3 |

Data are means±s.e.m. of n patients.

P<0.05 vs smokers;

P<0.001 vs smokers.

Spontaneous O2− production was subtracted from any determination with stimuli. O2− production is expressed as nmol cytochrome C reduced/106 AM.

Figure 1.

MSP evokes O2− production in AM. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with increasing concentrations of MSP (3–500 ng ml−1) for 30 min; •=smokers, ○=non-smokers. Results are means±s.e.m. of six to 10 experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs non-smokers.

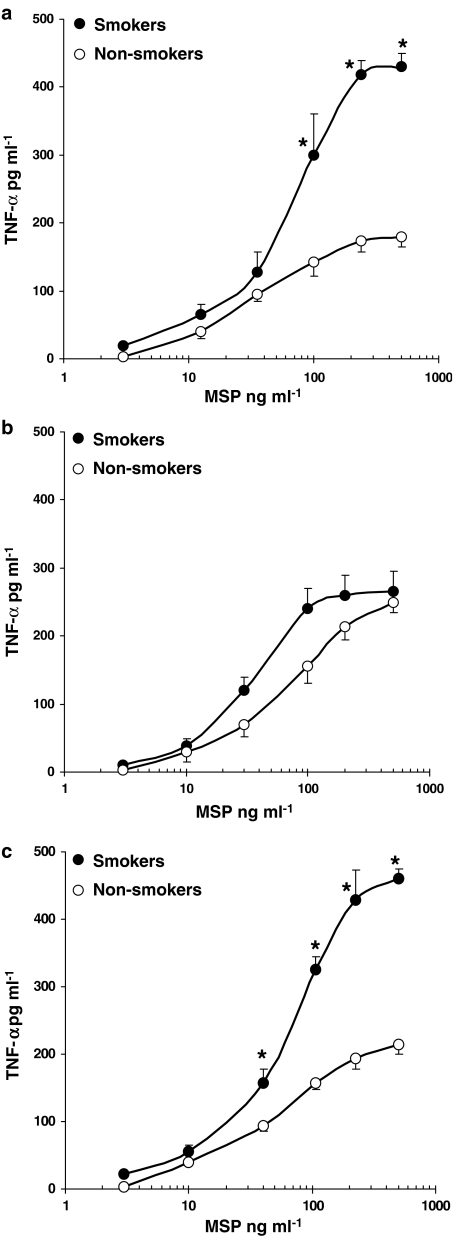

MSP-evoked cytokine release in AM

We also evaluated the release of proinflammatory cytokines, namely TNF-α and IL-1β, as well as IL-10 release (the most relevant anti-inflammatory cytokine in AM), after challenge with MSP or the standard stimuli PMA, FMLP or LPS. Basal values (i.e. the release from control, unstimulated AM) were subtracted from all determinations and are listed in Table 4: TNF-α represents the most abundant cytokine in AM and is spontaneously released to significant higher amounts in healthy smokers (P<0.05 vs non-smokers) and patients with interstitial lung diseases.

Table 4.

Basal release of cytokines in AM

| Subjects | TNF-α (pg ml−1) | IL-1β (pg ml−1) | IL-10 (pg ml−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Healthy | |||

| Smokers (n=5) |

63±3 |

10±0.5 |

30±3 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) |

35±2* |

8±2 |

49±4 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Sarcoidosis | |||

| Smokers (n=5) |

139±10 |

39±4 |

20±11 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) |

137±14 |

35±2 |

10±3 |

| |

|

|

|

|

Pulmonary fibrosis | |||

| Smokers (n=5) |

146±20 |

50±6 |

38±13 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) | 91±13* | 30±8 | 36±15 |

Values are means±s.e.m. of experiments in duplicate.

P<0.05 vs smokers.

As reported in Table 5, dealing with FMLP-, PMA- and LPS-evoked cytokine release, TNF-α is the cytokine released to significant higher amounts by all stimuli in all patients, LPS is the most effective AM stimulus for cytokine release from human AM, whereas PMA evoked no IL-10 release above baseline levels in all subjects (Table 4).

Table 5.

FMLP-, PMA- and LPS-evoked cytokine release in AM

|

Subjects |

TNF-α (pg ml−1) |

IL-1β (pg ml−1) |

IL-10 (pg ml−1) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

FMLP |

PMA |

LPS |

FMLP |

PMA |

LPS |

FMLP |

PMA |

LPS |

| 10−6 M | 10−7 M | 10 ng ml−1 | 10−6 M | 10−7 M | 10 ng ml−1 | 10−6 M | 10−7 M | 10 ng ml−1 | |

|

Healthy | |||||||||

| Smokers (n=5) |

37±4 |

515±36 |

3230±80 |

55±10 |

120±30 |

475±40 |

35±6 |

12±4 |

385±11 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) |

11±5 |

112±30* |

1703±70* |

46±8 |

108±10 |

290±30 |

45±7 |

10±3 |

360±20 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sarcoidosis | |||||||||

| Smokers (n=5) |

30±5 |

596±45 |

3330±80 |

60±15 |

80±10 |

320±30 |

25±5 |

15±7 |

232±35 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) |

24±3 |

242±40* |

1780±80* |

30±10 |

50±22 |

242±28 |

29±3 |

12±3 |

442±80 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Pulmonary fibrosis | |||||||||

| Smokers (n=5) |

309±40 |

560±50 |

4.685±100 |

115±12 |

179±15 |

1.580±70 |

15±7 |

11±6 |

520±25 |

| Non-smokers (n=5) | 65±20 | 240±30* | 3.380±40* | 70±8 | 80±8 | 890±20 | 20±5 | 10±4 | 816±40 |

Data are means±s.e.m. of n patients. AM were challenged for 24 h with FMLP 10−6 M, PMA 10−7 M or LPS 10 ng ml−1.

P<0.05 vs smokers.

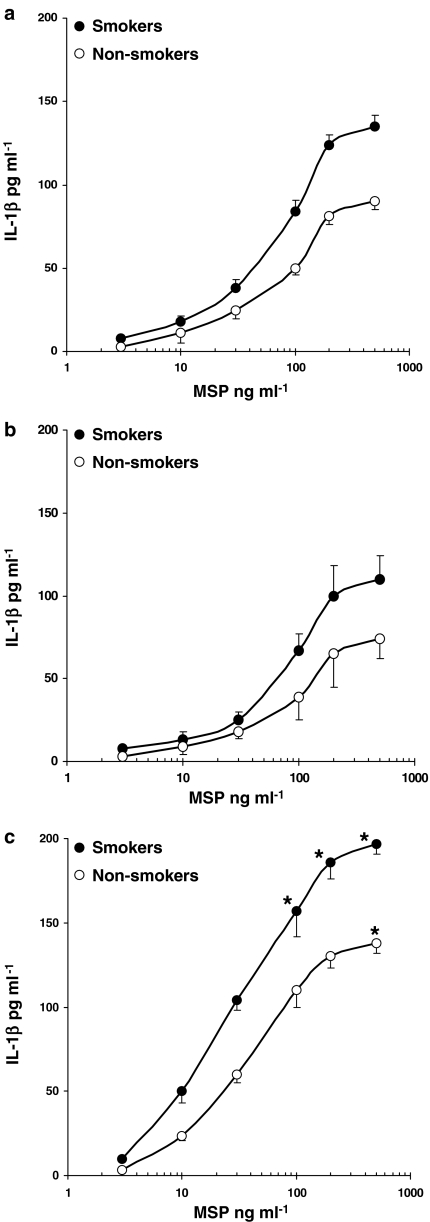

In the concentration range 3–500 ng ml−1, MSP induced TNF-α release from AM and was more effective in AM from healthy smokers (Figure 2a; P<0.05) and smokers with IPF (Figure 2c; P<0.05) as compared to non-smokers (Figure 2). No major differences between smokers and non-smokers were observed in AM from sarcoidosis patients (Figure 2b). To assess the specificity of MSP response, we used a commercial monoclonal anti-human MSP β-chain antibody (R&D), which, at 2 μg ml−1, inhibited 90% of the MSP-evoked TNF-α release in healthy smokers (data not shown). By evaluating IL-1β production from human AM, we observed that MSP acted in a concentration-dependent manner, maximal release being documented in smokers with IPF (Figure 3c). In healthy subjects and sarcoidosis patients, MSP-evoked IL-1β release was similar in smokers and non-smokers (Figure 3a and b).

Figure 2.

MSP evokes TNF-α release in AM. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with increasing concentrations of MSP (3–500 ng/ml) for 24 h; •=smokers, ○=non-smokers. Results are means±s.e.m. of five experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs non-smokers.

Figure 3.

MSP evokes IL-1β release in AM. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with increasing concentrations of MSP (3–500 ng/ml) for 24 h; •=smokers, ○=non-smokers. Results are means±s.e.m. of five experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs non-smokers.

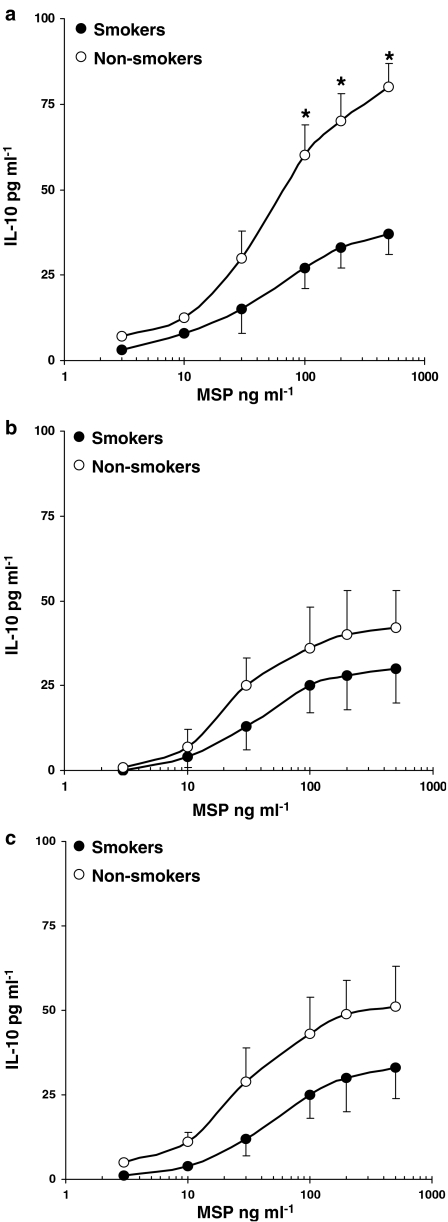

In keeping with our previous observations (Bardelli et al., 2005), human AM released lower amounts of IL-10, as compared to other cytokines (Figure 4). MSP-induced IL-10 release in AM from healthy non-smokers was higher (P<0.05) than in healthy smokers (Figure 4a) and was quantitatively reduced in AM obtained from patients with sarcoidosis (Figure 4b) and IPF (Figure 4c). Similar results were observed by evaluating MSP-induced cytokine release in MDM obtained from both healthy smokers and non-smokers (data not shown).

Figure 4.

MSP evokes IL-10 release in AM from smokers and non-smokers. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with increasing concentrations of MSP (3–500 ng/ml) for 24 h.; •=smokers, ○=non-smokers. Results are means±s.e.m. of five experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs smokers.

MSP induces NF-κB activation

In EMSA studies, we recently reported that AM from healthy smokers present an enhanced nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB as compared to AM from healthy non-smokers, the p50 subunit of NF-κB being the predominant one (Bardelli et al., 2005). Others have reported that NF-κB activity is elevated in AM collected from patients with active sarcoidosis (Culver et al., 2004) or fibrosing alveolitis (Conron et al., 2002). As large numbers of cells are required in these studies, we used MDM from individual smokers and non-smokers for EMSA studies (5–10 × 106 cells per sample). We used AM (2–3 × 106 cells per sample) to measure the nuclear content of p50 and p65 subunits by an ELISA kit, to ensure a better quantitative evaluation. Although different NF-κB forms have been described, the p50–p65 heterodimer is the predominant species in many cell types (Baldwin, 1996).

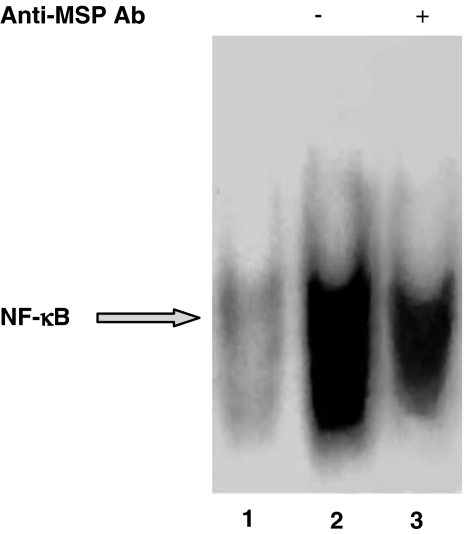

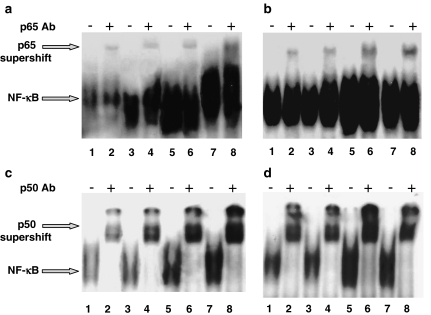

Gel shift analysis demonstrates that MSP 100 ng ml−1 induced NF-κB activation in MDM from healthy non-smokers (Figure 5). As previously demonstrated (Wang et al., 1997), MSP binds to its receptor RON via the β-chain; so, to confirm the ligand specificity in the activation of NF-κB, we used a commercial monoclonal antibody against human MSP β-chain. In the presence of this antibody (2 μg ml−1, preincubated for 45 min), the nuclear translocation induced by MSP was significantly reduced (Figure 5). MSP at two different concentrations, 50 and 100 ng ml−1, induced NF-κB activation in MDM from both healthy smokers and non-smokers (Figure 6); in keeping with Bardelli et al. (2005), we detected a relevant spontaneous activation in MDM from healthy smokers (Figure 6b and d; control, lane 1), which is significantly higher than in non-smokers (Figure 6a and c; control, lane 1). The effect of MSP is concentration-dependent and, in smokers, even higher than the LSP-induced one (Figure 6b and d). Figure 6 also shows supershift assays for p65 in both non-smokers (Figure 6a) and smokers (Figure 6b), as well as for p50 (Figure 6c: non-smokers; Figure 6d: smokers). In any case, p65 supershift is weak, thereby suggesting that it is not the major component involved in the activation, whereas p50 is potently supershifted (Figure 6).

Figure 5.

MSP evokes NF-κB activation in human MDM from healthy non-smokers. MDM from healthy non-smokers were challenged with MSP in the absence or presence of a monoclonal anti-MSP antibody (2 μg ml−1). Lane 1=unstimulated, control MDM; lane 2=MSP 100 ng ml−1; lane 3: MSP+anti-MSP antibody. This experiment was performed three times with similar results.

Figure 6.

MSP evokes NF-κB activation in human MDM from healthy non-smokers and smokers: supershift assays. MDM from healthy non-smokers (a and c) and smokers (b and d) were challenged with MSP (50 and 100 ng ml−1) or LPS 500 ng ml−1 for 2 h. Nuclear extracts (5 μg) were prepared and assayed for NF-κB activity by EMSA (see text for further details). In (a) and (b), supershifts with p65 antibody; in (c) and (d), supershift with p50 antibody. Lanes 1 and 2=unstimulated, control MDM; lanes 3 and 4=MSP 50 ng ml−1; lanes 5 and 6=MSP 100 ng ml−1; lanes 7 and 8=LPS 500 ng ml−1. Experiments here depicted were performed with MDM from different individual donors: this fact could explain the different shape and intensity of the gel.

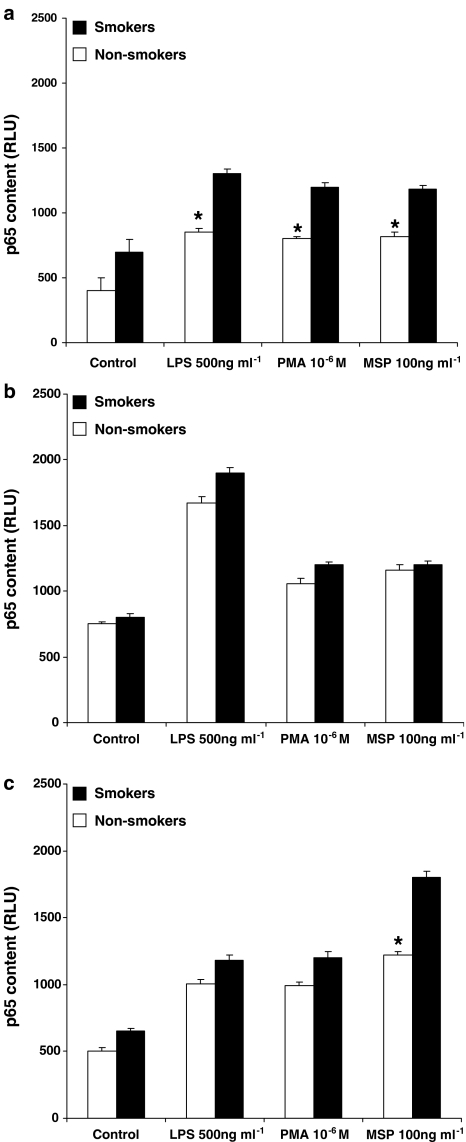

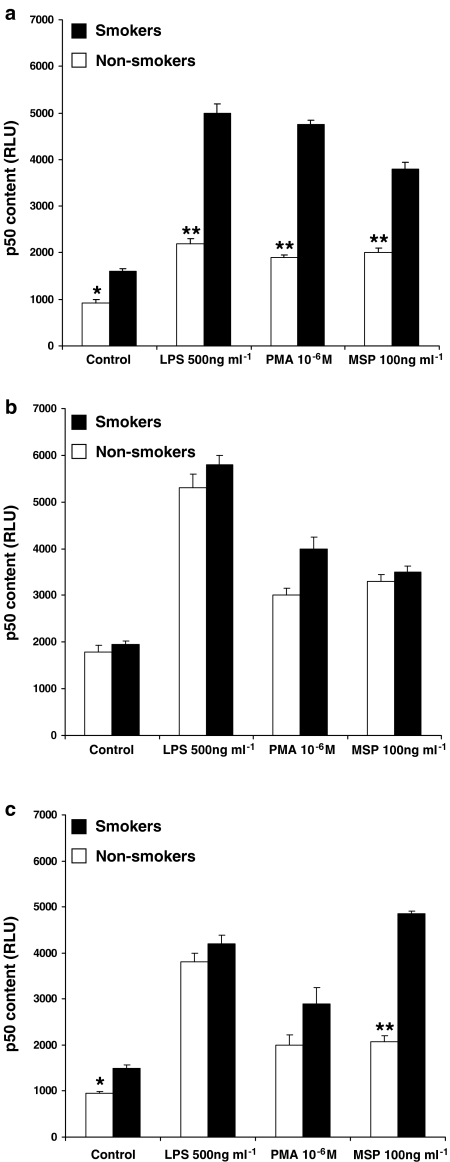

To ensure a better quantitative evaluation, we also assessed the translocation of p65 and p50 subunits in AM from healthy subjects (three smokers and three non-smokers), patients with sarcoidosis (three smokers and three non-smokers) or IPF (three smokers and three non-smokers), using a commercially available ELISA kit. First of all, we confirmed our previous observation (Bardelli et al., 2005) that the p50 subunit is the more abundant and/or more translocated one. In fact, RLU values for p50 are about two-fold higher than those measured for p65 in each group of patients (please, see, for a comparison, Figures 7 and 8). As depicted in Figure 7 (dealing with p65 subunit), MSP, LPS and PMA induced the nuclear translocation of this subunit. Interestingly, MSP induced an enhanced (P<0.05) nuclear translocation of p65 subunit in AM from healthy smokers (Figure 7a) and smokers with IPF (Figure 7c) as compared to non-smokers, so confirming what observed by measuring the respiratory burst (see Figure 1) and TNF-α release (see Figure 2). Moreover, in keeping with previous demonstrations (Culver et al., 2004), NF-κB activity in AM from non-smokers with sarcoidosis was upregulated, as revealed by the high amounts of translocated p65 subunit in unstimulated AM (Figure 7b). In this case, no significant differences were observed between smokers and non-smokers after MSP challenge (Figure 7b). By evaluating the nuclear translocation of the p50 subunit (Figure 8), MSP was particularly effective in AM from healthy smokers (Figure 8a) and IPF smokers (Figure 8c), but induced a similar effect in AM from sarcoidosis patients (Figure 8b), as already observed with p65. It is also worth noting that, in AM from IPF patients, MSP is the only stimulus which induced a more than doubled p50 nuclear translocation in smokers as compared to non-smokers (P<0.01), the amount of translocated p50 reaching about 5000 RLU (Figure 8c).

Figure 7.

MSP induces the translocation of p65 subunit in AM. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with MSP 100 ng ml−1, PMA 10−6 M or LPS 500 ng ml−1 for 2 h. Nuclear extracts (1 μg) were prepared and evaluated for their content in p65 subunit. Results are expressed as relative luminescence units (RLU) and are means±s.e.m. of three experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs smokers.

Figure 8.

MSP induces the translocation of p50 subunit in AM. AM from healthy smokers and non-smokers (a), patients with sarcoidosis (b) and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (c) were challenged with MSP 100 ng ml−1, PMA 10−6 M or LPS 500 ng ml−1 for 2 h. Nuclear extracts (1 μg) were prepared and evaluated for their content in p50 subunit. Results are expressed as relative luminescence units (RLU) and are means±s.e.m. of three experiments in duplicate. *P<0.05 vs smokers; **P<0.001 vs smokers.

Discussion

Several observations indicate that growth factors and proinflammatory cytokines are exaggerated in fibrotic lung diseases (Krein & Winston, 2002; Ziegenhagen & Muller-Quernheim, 2003; Khalil & O'Connor, 2004). A growing body of evidence suggests that hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which shares 45% homology with MSP and belongs to the same receptor family, could play an important role. In fact, enhanced HGF concentrations have been documented in sera from patients with IPF (Hojo et al., 1997; Yamanouchi et al., 1998), in BAL from sarcoidosis or IPF patients (Sakai et al., 1997), and a defective HGF secretion by lung fibroblasts has been related to IPF development (Marchand-Adam et al., 2003). As a member of the HGF family of growth factors, MSP has been evaluated for its effects in the lung. Currently, we recognize that the MSP/RON complex increases ciliary beat frequency of human nasal cilia (Sakamoto et al., 1997), is induced in early preneoplastic lung injury in hamster (Willett et al., 1997), is expressed in non-small-cell lung tumors (Willett et al., 1998) and stimulates oxy-radical production from human macrophages (Brunelleschi et al., 2001). Furthermore, MSP has been detected in induced sputum from normal subjects (about 8 ng ml−1; Takano et al., 2000), as well as in BAL from four healthy non-smokers, at concentrations ranging from 1.3 to 5.8 ng ml−1 (Sakamoto et al., 1997).

We report here that MSP, in a concentration-dependent manner, induces significant respiratory burst and cytokine release in AM from patients with interstitial lung diseases and healthy volunteers, both smokers and non-smokers. This growth factor mainly acts at concentrations higher than those measured in BAL, even if it is worth reminding that the absolute concentration of MSP in the broncho-alveolar spaces, where AM are located, should be higher (Sakamoto et al., 1997). We measured a significantly (P<0.05) increased O2− production when AM from healthy smokers or IPF smokers were challenged with MSP; on the contrary, no major differences were observed between smokers and non-smokers in the sarcoidosis group, despite the relevant respiratory burst induced by MSP. Regardless of the clinical condition evaluated, this growth factor is a potent AM stimulus, since MSP-induced respiratory burst is quantitatively similar to the PMA-evoked one and significantly higher than the FMLP-evoked one. These observations extend our previous data in human macrophages of different origin (Brunelleschi et al., 2001). Among the numerous cytokines involved in lung diseases, TNF-α has been appreciated as a crucial mediator for IPF and sarcoidosis (Ziegenhagen and Muller-Quernheim, 2003). In our experiments, MSP evoked the secretion of TNF-α in AM from all patients, a more than doubled release being observed, at the highest concentrations evaluated, in healthy smokers and IPF smokers as compared to the respective non-smoker groups. MSP also induced IL-1β release from AM, no significant differences being observed between smokers and non-smokers, except for the IPF group. In keeping with the fact (see below) that MSP activates NF-κB signalling, this result was somewhat unexpected. However, both PMA and LPS, although activating NF-κB and inducing cytokine secretion, did not release an enhanced amount of IL-1β in smokers (Bardelli et al., 2005; this paper). We have no conclusive explanation for this effect, but we remind that TNF-α and IL-1β production can be induced also through NF-κB-independent pathways (Bardelli et al., 2005). We and others (Conron et al., 2001; Ziegenhagen & Muller-Quernheim, 2003; Bardelli et al., 2005) observed that AM from smokers and sarcoidosis patients spontaneously produce a number of proinflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, but little of the immunoregulatory cytokine IL-10. Interestingly, MSP released higher amounts of IL-10 in AM from healthy non-smokers. This represents a peculiar feature of MSP: in fact, PMA- and FMLP-evoked release was negligible, whereas LPS released similar amounts in smokers and non-smokers of the three groups. As previously documented, IL-10 exerts anti-inflammatory effects and inhibits NF-κB activation in LPS-stimulated human AM (Raychaudhuri et al., 2000).

There is mounting evidence that NF-κB activation is important in the pathogenesis of different pulmonary diseases: elevated levels of NF-κB have been detected in AM obtained from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome, sarcoidosis or IPF (Schwartz et al., 1996; Conron et al., 2001; Culver et al., 2004), but not in cells from healthy non-smokers (Farver et al., 1998). In the majority of unstimulated cells, NF-κB is located in the cytoplasm as a heterodimer or homodimer of protein components (p50 and p65, mainly) bound to an inhibitor IκB protein (Baldwin, 1996). Activation of this transcription factor involves sequential phosphorylation, ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of IκBα, resulting in the migration of the NF-κB complex to the nucleus and binding to promoter region of many cytokine and growth factor genes (Baldwin, 1996).

The presence of potential NF-κB sites in the STK/RON promoter was demonstrated some years ago (Waltz et al., 1998): however, only a few reports are available in the literature concerning MSP effects on NF-κB signalling.

We originally report here that, in human AM and MDM from both smokers and non-smokers, MSP efficiently activates NF-κB: at 100 ng ml−1, a concentration which represents the EC50 value for the respiratory burst in healthy non-smokers, MSP is about as effective (or even more effective, see below) as PMA and LPS. As we reported previously, NF-κB is constitutively activated in healthy smokers (Bardelli et al., 2005); in this case, MSP-induced NF-κB nuclear translocation in MDM resulted in a two-fold increase over baseline and was more intense than the LPS-evoked one. Different NF-κB complexes are generated in AM from healthy volunteers; Carter et al. (1998) reported that specific NF-κB complexes are used for the transcription of various cytokine genes and that the p50 subunit binds the TNF-α sequence, mainly. A previous paper of our group demonstrated that the p50 subunit is the most abundant one in AM from both smokers and non-smokers, and is more efficiently translocated in smokers (Bardelli et al., 2005). We further confirm these observations by showing a weak p65 supershift but a very intense p50 supershift in MDM, and a doubled nuclear translocation of p50 (but about the same for p65) in unstimulated AM from healthy smokers as compared to non-smokers. In addition, there is a good correlation between the results of the p50 supershift assay and those obtained by the ELISA kit. When AM were challenged by PMA, LPS or MSP, a further enhanced nuclear translocation of NF-κB subunits was observed: all stimuli were particularly effective on p50 translocation (2.3–3-fold above baseline control values). Even in this case, MSP effects were significantly enhanced in AM from healthy smokers and smokers with IPF. However, no major differences were observed in smokers and non-smokers with sarcoidosis after challenge with MSP or other stimuli. We have no definite explanation for this fact, but we think it could rely, at least partially, on the documented upregulation of NF-κB in this disease (Culver et al., 2004). On the contrary, MSP was very effective (about three-fold increase) in inducing the translocation of the p50 subunit in AM from IPF smokers.

The clinical relevance of this finding remains to be ascertained, but, in our opinion, it could support an intriguing role for MSP in IPF development. The somewhat different effects evoked by MSP in AM collected from patients with interstitial lung diseases could also depend on both the peculiar type of disease and the more or less enhanced baseline of cytokines and oxy-radicals, given the fact that these mediators play a relevant role in sarcoidosis and IPF. As it is known that the activity of NF-κB is enhanced by free radicals and proinflammatory cytokines (Baldwin, 1996; Bowie & O'Neill, 2000), it is tempting to speculate that MSP-evoked respiratory burst, as well as TNF-α release, largely contribute to MSP ability in activating the transcription factor NF-κB.

Overall, these observations indicate that MSP triggers O2− production, cytokine release and NF-κB activation in AM from healthy volunteers and patients with sarcoidosis or IPF, both smokers and non-smokers. To our knowledge, this is the first paper that describes such effects and suggests MSP as a possible contributor for tobacco smoke toxicity.

Acknowledgments

Research described in this article was supported by Philip Morris U.S.A. Inc. and by Philip Morris International grants.

Abbreviations

- AM

alveolar macrophages

- BAL

broncho-alveolar lavage

- FMLP

N-formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine

- IL-10

interleukin-10

- IL-1β

interleukin-1 beta

- IPF

idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- MDM

monocyte-derived macrophages

- MSP

macrophage-stimulating protein

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-kappa B

- O2−

superoxide anion

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RON, recepteur d'origine nantaise, the human receptor for MSP; STK

stem cell-derived tyrosine kinase, the murine receptor for MSP

- TNF-α

tumor necrosis factor-alpha

References

- ALBINA J.E. On the expression of nitric oxide synthase by human macrophages. Why no NO. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1995;58:643–649. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.6.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BALDWIN A.S. The NF-κB and Iκ-B proteins: new discoveries and insights. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1996;14:649–681. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BARDELLI C., GUNELLA G., VARSALDI F., BALBO P., DEL BOCA E., SEREN BERNARDONE I., AMORUSO A., BRUNELLESCHI S. Expression of functional NK1 receptors in human alveolar macrophages: superoxide anion production, cytokine release and involvement of NF-κB pathway. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;145:385–396. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BOWIE A., O'NEILL L.A. Oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappaB activation: a reassessment of the evidence in the light of recent discoveries. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2000;59:13–23. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00296-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BRUNELLESCHI S., PENENGO L., LAVAGNO L., SANTORO C., COLANGELO D., VIANO I., GAUDINO G. Macrophage stimulating protein (MSP) evokes superoxide anion production by human macrophages of different origin. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2001;134:1285–1295. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CARTER A.B., MONICK M.M., HUNNINGHAKE G.W. Lipopolysaccharide-induced NF-κB activation and cytokine release in human alveolar macrophages is PKC-independent and TK- and PC-PLC-dependent. Am. J. Resp. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1998;18:384–391. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.3.2972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHEN Y.Q., FISHER J.H., WANG M.H. Activation of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression by murine peritoneal exudates macrophages: phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase is required for RON-mediated inhibition of iNOS expression. J. Immunol. 1998;161:4950–4959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONRON M., ANDREAKOS E., PANTELIDIS P., SMITH C., BEYNON H.L.C., DUBOIS R.M., FOXWELL B.M.J. Nuclear Factor-κB activation in alveolar macrophages requires IκB kinase-β, but not nuclear factor-κB inducing kinase. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2002;165:996–1004. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2107058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CONRON M., BONDESON J., PANTEDELIS P., BEYNON H.L.C., FELDMAN M., DUBOIS R.M., FOXWELL B.M.J. Alveolar macrophages and T cells from sarcoid, but not normal lung, are permissive to adenovirus infection and allow analysis of NF-κB-dependent signalling pathways. Am. J. Resp. Cell Mol. Biol. 2001;25:141–149. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.2.4327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CORRELL P.H., IWAMA S., TONDAT G., MAYRHOFER G., SUDA T., BERNSTEIN A. Deregulated inflammatory response in mice lacking the STK/RON receptor tyrosine kinase. Genes Funct. 1997;1:69–73. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4624.1997.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CULVER D.A., BARNA B.P., RAYCHAUDHURI B., BONFIELD T.L., ABRAHAM S., MALUR A., FARVER C.F., KAVURU M.S., THOMASSEN M.J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ activity is deficient in alveolar macrophages in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am. J. Resp. Cell. Mol. Biol. 2004;30:1–5. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2003-0304RC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FARVER C.F., RAYCHAUDHURI B., BUHROW L.T., CONNORS M.J., THOMASSEN M.J. Constitutive NF-κB levels in human alveolar macrophages from normal volunteers. Cytokine. 1998;10:868–871. doi: 10.1006/cyto.1998.0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOJO S., FUJITA J., YOSHINOU0CHI T., YAMANOUCHI H., KAMEI T., YAMADORI I., OTSUKI Y., UEDA N., TAKAHARA T. Hepatocyte growth factor and neutrophil elastase in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Resp. Med. 1997;91:511–516. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(97)90083-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IWAMA A., WANG M.H., YAMAGUCHI N., OHNO N., OKANO K., SUDO T, TAKEYA M., GERVAIS F., MORISETTE C, LEONARD E.J., SUDA T. Terminal differentiation of murine resident peritoneal macrophages is characterized by expression of the STK protein tyrosine kinase, a receptor for macrophage stimulating protein. Blood. 1995;86:3394–3403. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KHALIL N., O'CONNOR R. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: current understanding of the pathogenesis and the status of treatment. CMAJ. 2004;171:153–160. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.1030055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KREIN P.M., WINSTON B.W. Roles for insulin-like growth factor I and transforming growth factor-β in fibrotic lung disease. Chest. 2002;122:289S–293S. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6_suppl.289s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEONARD E.J., SKEEL A. A serum protein that stimulates macrophage movement, chemotaxis and spreading. Exp. Cell Res. 1976;102:434–438. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(76)90065-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU Q.P., FRUIT K., WARD J., CORRELL P.H. Negative regulation of macrophage activation in response to IFN-γ and lipopolysaccharide by the STK/RON receptor tyrosine kinase. J. Immunol. 1999;163:6606–6613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MARCHAND-ADAM S., MARCHAL J., COHEN M., SOLER P., GERARD B., CASTIER Y., LESECHE G., VALEYRE D., MAL H., AUBIER M., DEHOUX M., CRESTANI B. Defect of hepatocyte growth factor secretion by fibroblasts in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care Med. 2003;168:1156–1161. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200212-1514OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RAYCHAUDHURI B., FISHER C.J., FARVER C.F., MALUR A., DRAZBA J., KAVURU M.S., THOMASSEN M.J. Interleukin 10 (IL-10)-mediated inhibition of inflammatory cytokine production by human alveolar macrophages. Cytokine. 2000;12:1348–1355. doi: 10.1006/cyto.2000.0721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKAI T., SATOH K., MATSUSHIMA K., SHINDO S., ABE S., ABE T., MOTOMIYA M., KAWAMOTO T., KAWABATA Y., NAKAMURA T., NUKIWA T. Hepatocyte growth factor in bronchoalveolar lavage fluids and cells in patients with inflammatory chest diseases of the lower respiratory tract: detection by RIA and in situ hybridization. Am. J. Resp. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1997;16:388–397. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.4.9115749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAKAMOTO O., IWAMA A., AMITANI R., TAKEHARA T., YAMAGUCHI N., YAMAMOTO T., MASUYAMA K., YAMANAKA T., ANDO M., SUDA T. Role of macrophage-stimulating protein and its receptor, RON tyrosine kinase, in ciliary motility. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:701–709. doi: 10.1172/JCI119214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHWARTZ M.D., MOORE E.E., MOORE F.A., SHENKAR R., MOINE P., HAENEL J.B., ABRAHAM E. Nuclear factor-kappa B is activated in alveolar macrophages from patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit. Care Med. 1996;24:1285–1292. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199608000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TAKANO Y., SAKAMOTO O., SUGA M., SUDA T., ANDO M. Elevated levels of macrophage-stimulating protein in induced sputum of patients with bronchiectasis. Resp. Med. 2000;94:784–790. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALTZ S.E., TOMS C.L., MC DOWELL S.A., CLAY L.A., MURAOKA R.S., AIR E.L., SUN W.Y., THOMAS M.B., DEGEN S.J. Characterization of the mouse Ron/Stk receptor tyrosine kinase gene. Oncogene. 1998;16:27–42. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG M.H., JULIAN F.M., BREATHNAC R., GODOWSKI P.J., TAKEHARA T., YOSHIKAWA W., HAGIYA M., LEONARD E.J. Macrophage stimulating protein (MSP) binds to its receptor via the MSP β chain. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:16999–17004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.27.16999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WANG M.H., ZHOU Y.Q., CHEN Y.Q. Macrophage stimulating protein and RON receptor tyrosine kinase: potential regulators of macrophage inflammatory activities. Scand. J. Immunol. 2002;56:545–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.2002.01177.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLETT C.G., SMITH D.I., SHRIDHAR V., WANG M.H., EMANUEL R.L., PATIDAR K., GRAHAM S.A., ZHANG F., HATCH V., SUGARBAKER D.J., SUNDAY M.E. Differential screening of a human chromosome 3 library identifies hepatocyte growth factor-like/macrophage-stimulating protein and its receptors in injured lung. Possible implications for neuroendocrine cell survival. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:2979–2991. doi: 10.1172/JCI119493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLETT C.G., WANG M.H., EMANUEL R.L., GRAHAM S.A., SMITH D.I., SHRIDHAR V., SUGARBAKER D.J., SUNDAY M.E. Macrophage-stimulating protein and its receptor in non-small-cell lung tumors: induction of receptor tyrosine phosphorylation and cell migration. Am. J. Resp. Cell. Mol. Biol. 1998;18:489–496. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.18.4.2978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAMANOUCHI H., FUJITA J., YOSHINOUCHI T., HOJO S., KAMEI T., YAMADORI I., OHTSUKI Y., UEDA N., TAKAHARA J. Measurement of hepatocyte growth factor in serum and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid in patients with pulmonary fibrosis. Respir. Med. 1998;92:273–278. doi: 10.1016/s0954-6111(98)90108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZHOU Y.Q., CHEN Y.Q., FISHER J.H., WANG M.H. Activation of the RON receptor tyrosine kinase by macrophage stimulating protein inhibits inducible cyclooxygenase-2 expression in murine macrophages. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:38104–38110. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ZIEGENHAGEN M.W., MULLER-QUERNHEIM J.M. The cytokine network in sarcoidosis and its clinical relevance. J. Intern. Med. 2003;253:18–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2003.01074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]