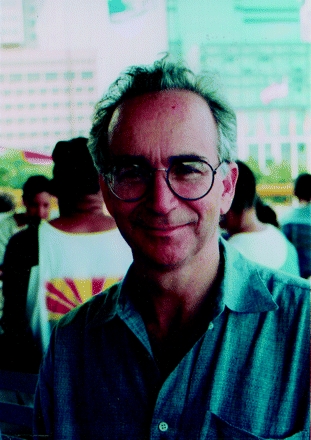

JONATHAN MANN COULD BE best characterized by 3 words: vision, audacity, and charisma. Mann would be nearing his 60th birthday had he not—together with his wife, Mary Lou Clements-Mann—been among the victims of a plane crash on September 2, 1998. Born in Boston, Mass, Jonathan graduated from Harvard College, studied at the Institut d’Études Politiques in Paris in 1967 and 1968, and obtained his MD from the Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, Mo, in 1974. In 1975 he joined the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as an epidemiological intelligence officer and was assigned to the New Mexico Health and Social Services Department as a state epidemiologist.

By 1977, Mann was New Mexico’s state epidemiologist, chief medical officer, and deputy director of the Health Services Department. By 1984, he was managing a staff of more than 400 and had published 58 articles, received 6 significant professional awards, and earned an MPH from the Harvard School of Public Health. Drawn to the challenges of the newly discovered AIDS epidemic, Mann moved his family to Zaire (today the Democratic Republic of the Congo), where a new AIDS research program was about to begin. Mann spent 2 intense years there, helping accumulate some of the initial epidemiological, clinical, and biomedical evidence on HIV and AIDS in an African context. In 1986, the Mann family—Jonathan; his first wife, Marie-Paule; their daughters, Naomi and Lydia; and their son, Aaron—moved to Geneva, where, after several years of hesitation, the World Health Organization (WHO) had embarked on a modest AIDS program.

Mann was assigned a small cubicle in the vast WHO headquarters. Within months, he had spearheaded the development of the first global strategy on HIV/AIDS, mobilized interest across industrialized and developing countries, and obtained promises of funding from potential donors. By January 1987, the Global Program on AIDS had been born. Mann recognized that HIV infection rates were closely connected to inequality, injustice, discrimination, and the failure of public health to recognize the deep roots of vulnerability worldwide. The program’s global strategy was unprecedented in international public health in that it specifically incorporated human rights principles. By 1990, the Global Program on AIDS had fostered a number of truly revolutionary policies and engaged nontraditional partners—sex workers, men who had sex with men, and drug users—to work with government officials and WHO staff in the fight against HIV/AIDS. By the end of 1989, 160 countries around the world had HIV/AIDS programs.

Mann spoke with convincing power and had a capacity to transmit empathy that had seldom been seen in public health forums. His eloquence and charisma made it possible for him to convey controversial social, cultural, and political issues in ways that his audience could understand and accept. He became a world leader in public health and a huge media personality. Some WHO leaders, perceiving Mann to be “too big” for the organization, took action to clip his wings. The organization lowered Mann’s public profile, imposed administrative constraints on the Global Program on AIDS, and—most important—toned down the human rights facet of WHO’s global AIDS strategy, which had generated discomfort among a few influential member states. Mann felt he had no choice but to resign from WHO in March 1990.

Mann then moved to the Harvard School of Public Health as a tenured professor and director of the International AIDS Center of the Harvard AIDS Institute. There, one of his early projects was to present a new vision of the HIV/AIDS pandemic in a book titled AIDS in the World,1 which explained how vulnerability to HIV was intertwined with the lack of realization of human rights. Four years later, he and collaborators showed how the lessons learned from the pandemic allowed a deeper understanding of the relation between health and society.2

As the founding director of the Harvard-based Francois-Xavier Bagnoud Center for Health and Human Rights, Mann laid the ground for development of a conceptual framework for health and human rights. Mann and colleagues described this framework in the first issue of the journal he founded, Health and Human Rights.3 He left Harvard in 1998 to become dean of the newly created school of public health at the Allegheny University of Health Sciences, Philadelphia, Pa. However, the school was shut down for financial reasons, and Mann and his second wife, Mary Lou—a renowned scientist in the field of vaccine research—decided to spend some time working in a developing country. They were on their way to discuss this at WHO headquarters when they boarded the ill-fated flight from New York to Geneva. Jonathan Mann projected a vision of modern public health—a vision that continues to inspire new generations of health and human rights practitioners.

References

- 1.Mann J, Tarantola D, Netter T, eds. AIDS in the World. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1992.

- 2.Mann J, Tarantola D, eds. AIDS in the World II. Oxford University Press; 1996.

- 3.Mann J, Gostin L, Gruskin S, Brennan T, Lazzarini Z, Fineberg H. Health and human rights. Health Hum Rights. 1994;1(1):6–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]