Abstract

The overall aim of this study was to determine if adrenomedullin (AM) protects against myocardial ischaemia (MI)-induced arrhythmias via nitric oxide (NO) and peroxynitrite.

In sham-operated rats, the effects of in vivo administration of a bolus dose of AM (1 nmol kg−1) was assessed on arterial blood pressure (BP), ex vivo leukocyte reactive oxygen species generation and nitrotyrosine deposition (a marker for peroxynitrite formation) in the coronary endothelium.

In pentobarbitone-anaesthetized rats subjected to ligation of the left main coronary artery for 30 min, the effects of a bolus dose of AM (1 nmol kg−1, i.v.; n=19) or saline (n=18) given 5 min pre-occlusion were assessed on the number and incidence of cardiac arrhythmias. In a further series of experiments, some animals received infusions of the NO synthase inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine (LNNA) (0.5 mg kg−1 min−1) or the peroxynitrite scavenger N-mercaptopropionyl-glycine (MPG) (20 mg kg−1 h−1) before AM.

AM treatment significantly reduced mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) and increased ex vivo chemiluminescence (CL) generation from leukocytes in sham-operated animals. AM also enhanced the staining for nitrotyrosine in the endothelium of coronary arteries.

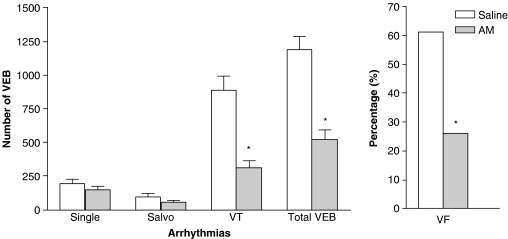

AM significantly reduced the number of total ventricular ectopic beats that occurred during ischaemia (from 1185±101 to 520±74; P<0.05) and the incidences of ventricular fibrillation (from 61 to 26%; P<0.05). AM also induced a significant fall in MABP prior to occlusion. AM-induced cardioprotection was abrogated in animals treated with the NO synthase inhibitor LNNA and the peroxynitrite scavenger MPG.

This study has shown that AM exhibits an antiarrhythmic effect through a mechanism that may involve generation of NO and peroxynitrite.

Keywords: Cardioprotection, adrenomedullin, anaesthetized rats, ischaemia, leukocytes, ventricular arrhythmias

Introduction

Adrenomedullin (AM) is a recently described peptide that has pronounced effects on the cardiovascular and renal systems (Kitamura et al., 1993a). In a wide variety of vascular beds, AM causes vasodilation (He et al., 1995) that leads to a fall in arterial blood pressure (BP) in vivo (Feng et al., 1994). This vasodilator effect is largely (but not exclusively) due to the generation of nitric oxide (NO) in the vasculature since it is reduced by a nitric oxide synthase (NOS) inhibitor or by de-endothelialization (Yang et al., 1996). In addition, AM has been shown to inhibit vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation (Chini et al., 1995) and apoptosis in endothelial cells (Kato et al., 1997). It has also been reported that AM has cytoprotective properties in a model of glomerular cell injury (Chini et al., 1997). Within the cardiovascular system, AM is produced by both the blood vessels and the heart (Kitamura et al., 1993b), and following myocardial infarction there is an increase in plasma (Kato et al., 1996) and ventricular AM levels (Nagaya et al., 2000). An increasing amount of evidence suggests that AM could be a cardioprotective agent. For example, endogenous AM has been demonstrated to be protective against myocardial injury in mice (Shimosawa et al., 2002; Niu et al., 2004) and in rats (Hamid & Baxter, 2005). In addition, Nakamura et al. (2002) demonstrated that continuous administration of AM had beneficial effects on left ventricular remodelling after myocardial infarction in rats. Furthermore, AM gene delivery attenuated myocardial infarction and apoptosis after myocardial ischaemia (MI) and reperfusion in rats (Kato et al., 2003). However, the possible mechanism(s) by which AM exerts cardioprotection is not fully understood. Moreover, the concept that AM may also protect against the electrophysiological consequences of ischaemia has not been explored.

A large body of evidence supports a cardioprotective and antiarrhythmic role for NO and peroxynitrite, a product of NO and superoxide, in the setting of MI and reperfusion. NO donors or the precursor for NO synthesis, L-arginine, can ameliorate reperfusion-induced arrhythmias in rats (Pabla et al., 1995; Bilinska et al., 1996) and reduce ischaemic/reperfusion injury in rabbits (Aitchison & Coker, 1999). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) have also been shown to be one of the triggers that can mimic the cardioprotective effects of preconditioning (Bilinska et al., 1996; Baines et al., 1997). Peroxynitrite, an ROS produced from an interaction between superoxide and NO, has been shown to contribute to the cardioprotective effects of ischaemic preconditioning in rats (Altug et al., 2000) as well as acting as a ‘pharmacological' preconditioning agent in rats (Lefer et al., 1997; Altug et al., 2001) and cats (Nossuli et al., 1997; 1998). Thus it is feasible that AM may induce cardioprotection through release of NO, with subsequent accumulation of peroxynitrite produced through interaction with superoxide.

The first aim of the present study was therefore to determine the effects of AM on haemodynamics, ROS generation from peripheral blood leukocytes and coronary endothelial peroxynitrite production in normal anaesthetized rats. Once these responses had been established, we examined the effect of exogenously administered AM on the cardiac arrhythmias produced by coronary artery occlusion in anaesthetized rats. Finally, in order to investigate the potential roles of NO and peroxynitrite in AM-induced cardioprotection, further coronary occlusion experiments with AM were performed in the presence of the NO synthase inhibitor N(G)-nitro-L-arginine (LNNA) and the peroxynitrite scavenger N-mercaptopropionyl-glycine (MPG).

Methods

Surgical procedure

All procedures were carried out in accordance with the United Kingdom Home Office Guide on the Operation of animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986. Animals were allowed free access to food and water and maintained on a 12-h light/dark cycle. Male Sprague–Dawley rats (250–400 g) were anaesthetized with sodium pentobarbitone (60 mg kg−1 i.p.) and maintained under anaesthesia by additional injections (6 mg i.v.) as required. The trachea was cannulated for artificial respiration using a rodent respirator (Scientific & Research Instruments, U.K., tidal volume 1.5 ml 100 g−1, rate 54 strokes min−1). Blood was withdrawn for blood gas analysis (Synthesis 10, Instrumentation Laboratory, U.S.A.) to ensure adequate ventilation throughout the experiment (pCO2 18–24 mmHg, pO2 100–130 mmHg, pH 7.4). Systemic arterial BP was recorded via a catheter inserted into the left carotid artery and attached to a BP transducer (Gould, U.S.A.). The right jugular vein was cannulated for administration of drugs or additional anaesthetic as appropriate. Rectal temperature was recorded via a precalibrated steel thermistor probe and core temperature maintained at 37–38°C with the aid of a heating lamp. A standard limb lead I electrocardiogram (ECG) was recorded from subcutaneous limb leads. Both the ECG and BP were continuously recorded on a Gould polygraph recorder (Gould, U.S.A.). Mean arterial blood pressure (MABP) was calculated from the BP trace, whereas the heart rate (HR; beats per minute; b.p.m.) was calculated from the ECG. A left thoracotomy was performed and the heart prepared for coronary artery ligation using the method previously described by Clark et al. (1980). A 6/0 braided silk suture attached to a 10 mm micropoint reverse cutting needle (Mersilk, Ethicon, Belgium) was inserted (approximately 0.5 mm) into the myocardium 2–3 mm away from the origin of the left main coronary artery. In sham-operated animals, the ligature was left untied; however, in studies looking at the effect of AM on coronary occlusion-induced arrhythmias, coronary occlusion was achieved by tightening the ends of the suture by a pair of clamps.

Assessment of arrhythmias

Ventricular arrhythmias were assessed according to the guidelines of the Lambeth Conventions for the analysis of experimental arrhythmias (Walker et al., 1988). Arrhythmias were counted as single ventricular ectopic beats, couplets and triplets (salvos) and ventricular tachycardia (VT). In animals that survived the 30 min of ischaemia, the total number of ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs) was summed. The incidences of ventricular fibrillation (VF), VT and mortality within each experimental group were also recorded. Animals were excluded from the study if spontaneous arrhythmias were observed prior to coronary artery occlusion or if the initial MABP was less than 70 mmHg. Animals that failed to survive the ischaemic period were also excluded from the statistical analysis of haemodynamic parameters and VEBs.

Ex vivo chemiluminescence measurement

ROS generated from peripheral leukocytes was measured using a modification of the luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence (CL) method previously described by us (Demiryürek et al., 1997). Briefly, immediately after withdrawal from the animal, 90 μl of whole blood containing citrate (0.038%, final concentration) was added to a cuvette containing 810 μl of Hank's balanced salt solution that was preheated to 37°C for 5 min. The cuvette was then placed into the chamber and the baseline was set. Then, 100 μl of luminol (2 mM) was added into the cuvette, followed by the addition of 10 μl of zymosan A (from Saccharomyces cerevisiae). A minute of incubation time was then allowed for the stimulation of respiratory burst from leukocytes by zymosan A before starting the integration of the emitted signal for 15 min. CL emitted was expressed as the total count recorded in the digital display panel. For blood samples withdrawn throughout the experimental protocol, the total CL count was expressed as a percentage of the basal CL reading.

Nitrotyrosine immunostaining

Immunocytochemical staining for nitrotyrosine was performed in heart sections from sham-operated and MI animals that were administered bolus AM (1 nmol kg−1) or saline and the hearts were removed 35 min later (i.e. equivalent to the 30 min post-occlusion time point) using a method previously described by us (Demiryürek et al., 2000). Cross-sectional slices of the hearts were fixed in 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline, wax embedded and 3 μm thick transverse sections cut and mounted on polysilane-coated slides. Following deparaffinization, endogenous peroxidases activity was quenched by incubating the sections in 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min, followed by washing in Tris-buffered saline for 5 min. The sections were then incubated in freshly prepared 0.1% trypsin dissolved in 0.1% calcium chloride solution in Tris Buffer at 37°C for 25 min. Nonspecific binding was prevented by incubating the sections in 20% normal goat serum, 5% normal rat serum and 3% bovine serum albumin solution in Tris-buffered saline. Endogenous avidin and biotin were then suppressed by the sequential 15 min application of avidin and biotin blocking kit. Subsequently, the primary antibody (rabbit anti-nitrotyrosine) was applied for a period of 1 h at a dilution of 1 : 250. Specific labelling was detected by the Labelled Streptavidin-Biotin® 2 System (LSAB® 2 System, DAKO, U.K.). Peroxidase activity was detected using diamino-benzidine, which yielded a dark-brown reaction product at the sites of nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity. The sections were then counterstained with haematoxylin and then incubated in 0.5% copper sulphate solution for 10 min to intensify the brown end product. Each staining run contained a negative and a positive control slide (chronic hypoxic rat lung; Demiryürek et al., 2000).

Experimental protocols

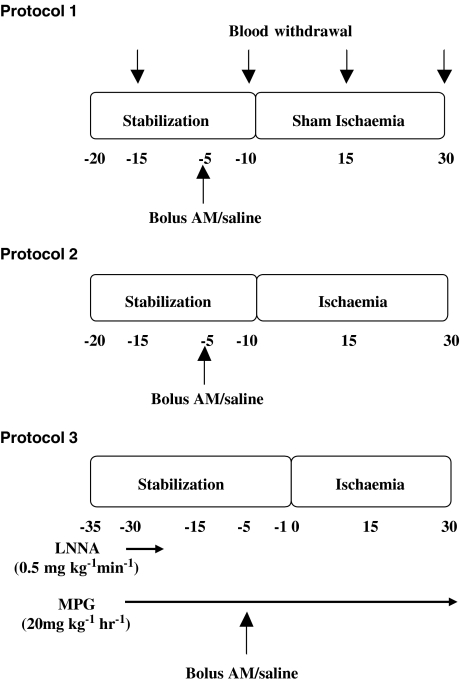

Preliminary studies in closed-chest rats to determine an appropriate dose of AM revealed that 0.3 nmol kg−1 had no effect on MABP, whereas 1 and 3 nmol kg−1 reduced MABP by approximately 10 and 50%, respectively. Thus for the remaining studies, the dose of 1 nmol kg−1 was chosen owing to its minimal effects on BP. Figure 1 illustrates the experimental protocols employed.

Figure 1.

Experimental protocols.

Protocol 1 – studies on the effects of AM in sham-operated rats

Animals were allowed a 20 min-stabilization period after the surgical procedure. A bolus dose of AM (1 nmol kg−1; i.v.; n=8) or an equal volume of 0.9% saline (n=6) was given 5 min before ‘sham' MI and the ECG and BP were monitored continuously. Blood was withdrawn at 15 min intervals for the determination of ROS production from leukocytes. At the end of the experiment, the hearts were removed for immunocytochemical staining of heart sections for nitrotyrosine.

Protocol 2 – studies to determine the effects of AM on coronary occlusion-induced arrhythmias

Following stabilization, a bolus dose of AM (1 nmol kg−1; i.v.; n=19) or an equal volume of 0.9% saline (n=18) was given 5 min before coronary artery occlusion. The consequent arrhythmias and haemodynamics were monitored for 30 min. Blood was withdrawn at 15 min intervals for the determination of ROS production from leukocytes. At the end of the experiment, the hearts were removed for immunocytochemical staining of heart sections for nitrotyrosine.

Protocol 3

To determine the contribution of NO and peroxynitrite to the antiarrhythmic effect of AM, rats were given either a 10 min intravenous infusion of the NOS inhibitor LNNA (0.5 mg kg−1 min−1) or a continuous intravenous infusion of the peroxynitrite scavenger MPG (20 mg kg−1 h−1), each started 30 min prior to coronary artery occlusion. In both experiments, either AM (1 nmol kg−1) or saline was then given 5 min prior to occlusion (n=10 for each experimental group). Blood was withdrawn at 15 min intervals for determination of ROS production from leukocytes. At the end of the experiment, the hearts were removed for immunocytochemical staining of heart sections for nitrotyrosine.

Materials

Drugs and chemicals used were human AM, LNNA, MPG, zymosan A, luminol, Hank's balanced salt solution, diamino-benzidine (all from Sigma, Poole, U.K.); pentobarbitone sodium (Sagatal, Rhône Mérieux, Essex, U.K.); avidin and biotin blocking kit (Vector Lab, Burlinghame, U.S.A.); LSAB® 2 System kit (DAKO, Ely, U.K.); anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Upstate, Lake Placid, U.S.A.). AM stock solution (of 10−5 M) was prepared by dissolving AM desiccate in 0.9% NaCl. Zymosan A was prepared by boiling 10 mg in 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl for 10 min. Following this, the solution was centrifuged for 5 min at 1200 r.p.m. and resuspended in 10 ml of 0.9% NaCl.

Data analysis

Values are expressed as the mean and the standard error of the mean. Statistical comparisons within groups were performed using repeated measures ANOVA and Dunnett's multiple comparison post hoc tests. Comparisons between groups were performed by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's multiple comparison post hoc tests where applicable. Differences in the incidence of VT, mortality and VF were determined by Fisher's exact test. The degree of staining for nitrotyrosine was scored as followed: 0=negative or the same level as background staining, 1=mild positivity, 2=moderate positivity, 3=intense positivity. Staining grades were converted to a percentage where 100%=3 on the grading scale and 0%=0 on the grading scale. Dr A.R. McPhaden (consultant pathologist, Department of Pathology, Glasgow Royal Infirmary) carried out the histological quantification in a blinded fashion. Differences were considered significant when P<0.05.

Results

The effects of AM in sham-operated rats

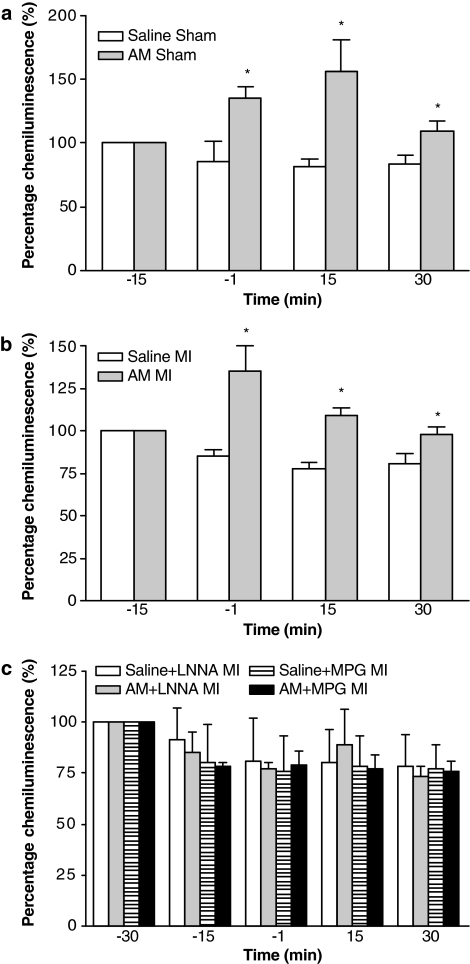

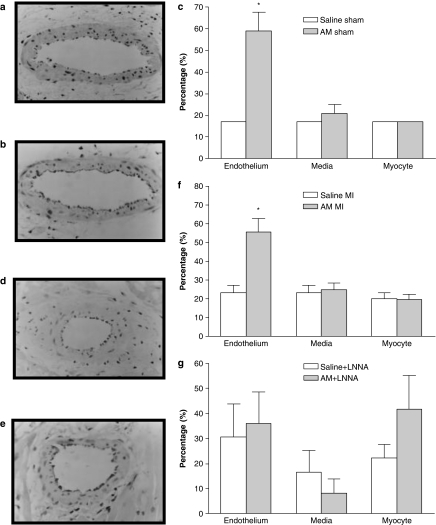

AM caused a significant and sustained reduction in MABP (Table 1) without inducing any changes in either HR or QT interval (data not shown). CL generated in whole blood after administration of AM in sham-operated animals was significantly increased 4 min following administration compared to the same time point in saline controls. This increased leukocyte ROS generation was maintained throughout the remainder of the experimental protocol (Figure 2a). In the heart sections of sham-operated animals treated with saline, only faint nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity within the endothelium was observed (Figure 3a), whereas in animals treated with AM significantly more intense staining for nitrotyrosine was evident within the endothelium (Figure 3b and c). Faint positivity was also observed in the media and myocytes from both AM-treated and saline-treated heart sections.

Table 1.

MABP and HR in sham-operated anaesthetized rats following administration of saline or AM

| |

MABP (mmHg) |

HR (b.p.m.) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time (min) | Saline (n=6) | AM (n=8) | Saline (n=6) | AM (n=8) |

| −15 |

111±3 |

113±5 |

460±13 |

473±12 |

| −5 |

112±7 |

115±8 |

455±9 |

469±14 |

| −1 |

108±7 |

106±10* |

440±13 |

461±15 |

| 1 |

109±7 |

98±9* |

440±13 |

458±16 |

| 15 |

113±9 |

85±8* |

450±11 |

458±14 |

| 30 | 110±8 | 82±8* | 455±6 | 450±10 |

Times correspond to time 0 being the point at which coronary ligation would be performed in coronary occlusion experiments. AM or saline was given at time −5 min.

P<0.05 indicates significantly different from −5 min value;

#P<0.05 indicates significantly different from −1 min value.

Figure 2.

Ex vivo luminol chemiluminescence, expressed as a percentage of baseline (with the control value equal to 100%), generated by activated leukocytes in whole blood withdrawn from saline (n=6)- and AM (n=8)-treated sham-operated animals (a); saline (n=13)- and AM (n=13)-treated animals subjected to MI (b); and saline+LNNA (n=7), AM+LNNA (n=8), saline+MPG (n=8) and AM+MPG (n=9) animals subjected to MI (c). *P<0.05 indicates significantly different from control.

Figure 3.

Representative immunocytochemical staining of nitrotyrosine in the heart sections of sham-operated animals that were treated with either saline (a) or AM (b), and in animals subjected to MI that were treated with either saline (d) or AM (e). Photomicrographs reveal enhanced brown nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity in the endothelium of coronary blood vessels of AM-treated animals compared to saline-treated animals. Magnification × 400. (c) Illustrates semiquantification of the expression of nitrotyrosine in the endothelium and media of coronary blood vessel and in the myocyte of sham-operated rat hearts (n=4). (f) Illustrates semiquantification of the expression of nitrotyrosine in the endothelium and media of coronary blood vessel and in the myocyte of MI hearts (n=5–6). (g) Illustrates semiquantification of the expression of nitrotyrosine in the endothelium and media of coronary blood vessels and in the myocytes of MI hearts pretreated with LNNA. (n=6). *P<0.05 indicates significantly different from the saline group.

Effects of AM on the consequences of coronary artery occlusion

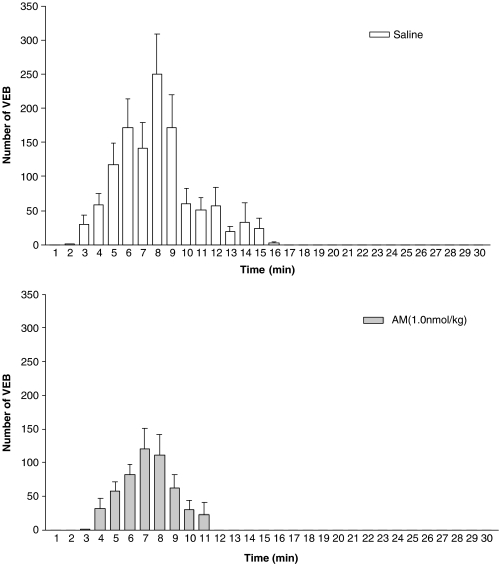

Coronary artery occlusion resulted in an immediate fall in arterial BP (Table 2), an increase in the amplitude of the R-wave of the electrocardiogram and subsequently the development of arrhythmias. Administration of AM prior to ischaemia resulted in a small but significant reduction in MABP prior to coronary occlusion. Following occlusion, the magnitude of the fall in MABP was significantly greater in AM-treated rats (59±3% reduction) than in saline-treated controls (45±6%). Figures 4 and 5 summarize the effects of AM on arrhythmias. AM significantly reduced the total number of VEBs over the 30 min of MI compared to saline-treated rats, predominantly through a reduction in the number of beats occurring as VT (Figure 4) during the 6–15 min post-occlusion period (Figure 5). Similarly, the total incidence of VF was markedly reduced by AM (Figure 4), although there was no effect on mortality owing to VT or VF between the groups (28 and 32% in the saline and AM treatment groups, respectively). CL generated in whole blood after administration of AM was significantly increased 4 min following administration (Figure 2b) and the increased leukocyte ROS generation was maintained throughout the remainder of the experimental protocol (Figure 2b). In the heart sections of animals treated with saline, only faint nitrotyrosine immunoreactivity within the endothelium was observed (Figure 3d), whereas in animals treated with AM significantly more intense staining for nitrotyrosine was evident within the endothelium (Figure 3e and f). Faint positivity was also observed in the media and myocytes from both AM-treated and saline-treated heart sections.

Table 2.

MABP in rats subjected to coronary artery occlusion following administration of saline or AM (1 nmol kg−1)

| Time (min) | Saline (n=13) | AM+MI (n=13) |

|---|---|---|

| −15 |

109±4 |

111±3 |

| −5 |

113±3 |

115±4 |

| −1 |

113±3 |

106±5* |

| 1 |

58±7# |

47±3# |

| 15 |

80±5# |

78±5# |

| 30 | 64±5# | 61±3# |

Saline or AM were administered at time −5 min and coronary occlusion was performed at time 0.

P<0.05 compared to −5 min value.

P<0.05 compared to −1 min pre-occlusion value.

Figure 4.

Numbers of ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs) and the percentage incidences of ventricular fibrillation (VF) in animals treated with saline (n=13 for VEB quantification, n=18 for VF percentage quantification) and AM (n=13 for VEB quantification, n=19 for VF percentage quantification). *P<0.05 indicates significantly different from the saline group.

Figure 5.

Minute by minute distribution of VEBs over the 30 min period of coronary artery occlusion in animals treated with saline (top panel, n=13) and AM (bottom panel, n=13).

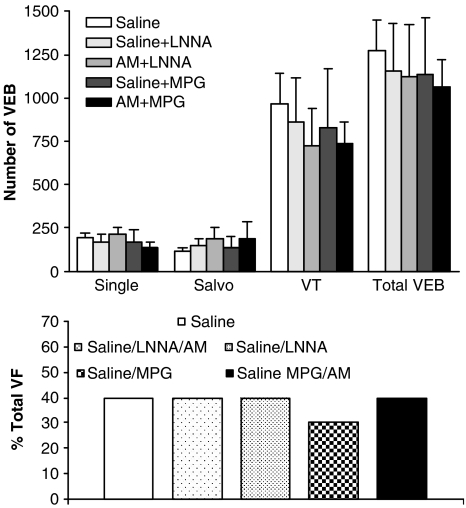

Effects of LNNA and MPG on AM-induced reduction in arrhythmias

Table 3 shows the MABP values in all animal groups. LNNA infusion caused a significant and sustained rise in MABP compared to saline control and prevented the AM-induced fall in MABP. MPG infusion itself did not modify MABP, nor did it block the depressor response to AM. However, MABP in the saline+MPG group was significantly lower than in the saline controls at the 30 min time point. HR was not significantly altered in response to any of the drug treatments or to coronary artery occlusion (data not shown). Neither LNNA nor MPG alone influenced either the total number of VEBs or the incidence of VF. In animals receiving LNNA infusion and subsequent administration of AM, the total number of VEBs was not significantly different from either the saline or LNNA alone groups (Figure 6). Similarly, in animals receiving MPG infusion before AM treatment, there was no significant difference in the total number of VEBs compared to either the saline or MPG alone groups. Furthermore, the incidences of VF were not significantly different among any of the groups (Figure 6). Mortality from irreversible VF or VT was similar among the groups (10, 30, 20, 10 and 20% in the saline, saline+LNNA, AM+LNNA, saline+MPG and AM+MPG treatment groups, respectively; NS). These data demonstrate that the antiarrhythmic effect of AM was not evident in the presence of either LNNA or MPG. CL generated in whole blood after administration of AM in all groups was not significantly different compared to the same time point in saline controls throughout the experimental protocol (Figure 2c). In addition, the intensity of nitrotyrosine staining in heart sections from rats pretreated with LNNA prior to administration of AM was not significantly different from staining intensity in the heart sections from animals administered only LNNA (Figure 3g). We were unable to stain sufficient heart sections from the MPG-treated groups to allow statistical analysis, however from the sections we did analyse, there was no apparent difference in staining intensity between MPG-treated rats with or without additional AM administration.

Table 3.

MABP (mmHg) in rats given either LNNA or MPG prior to administration of saline or AM with subsequent coronary artery occlusion

| Time (min) | Saline (n=9) | Sal+LNNA (n=7) | AM+LNNA (n=8) | Sal+MPG (n=8) | AM+MPG (n=9) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −35 |

107±5 |

113±5 |

118±4 |

107±5 |

117±4 |

| −15 |

99±5 |

163±5@,† |

163±6@,† |

118±8 |

119±7 |

| −5 |

111±6 |

162±5@,† |

163±4@,† |

109±7 |

114±7 |

| −1 |

108±5 |

160±5@,† |

161±4@,† |

105±7 |

101±7* |

| 1 |

60±2# |

93±9#,† |

87±7#,† |

56±6# |

61±5# |

| 15 |

100±6# |

106±11# |

101±10# |

72±10# |

80±8# |

| 30 | 81±5# | 88±9# | 76±10# | 53±7#,† | 62±7# |

LNNA was infused for 10 min from −30 min, while MPG was infused continuously from −30 min for the duration of the experiment. Saline or AM was then administered at time −5 min and coronary occlusion was performed at time 0.

P<0.05 indicates significantly different from −35 min value;

P<0.05 indicates significantly different from −5 min value;

P<0.05 indicates significantly different from −1 min value;

P<0.05 indicates significantly different from corresponding saline values.

Figure 6.

Numbers of ventricular ectopic beats (VEBs) in surviving animals pretreated with saline (n=9), saline+LNNA (n=7), AM+LNNA (n=8), saline+MPG (n=8) and AM+MPG (n=9). The bottom panel shows the percentage incidences of VF (n=10 for all groups).

Discussion

AM has previously been reported to induce a reduction in arterial BP (Ishiyama et al., 1993) which is thought to be mediated through the release of endothelium-derived NO (Feng et al., 1994; Nossaman et al., 1996; Hayakawa et al., 1999). Furthermore, AM has also previously been shown to induce protection against myocardial injury (Shimosawa et al., 2002; Niu et al., 2004; Hamid & Baxter, 2005). Here, we provide the first evidence that, in addition to causing the release of NO, AM also increases the production of ROS (including peroxynitrite) by activated peripheral blood leukocytes and the coronary vascular endothelium, and that both NO and peroxynitrite are involved in the newly demonstrated antiarrhythmic effect of AM.

In sham-operated rats, AM, given as a single bolus dose of 1 nmol kg−1, caused a significant reduction in arterial BP without inducing a reflex tachycardia. This is in agreement with previous studies conducted in anaesthetized rats (Ishiyama et al., 1993; He et al., 1995). Furthermore, and again in line with the literature, we demonstrated that this reduction in MABP was mediated by NO release since, in rats subsequently subjected to coronary occlusion, this effect was abrogated by the NO synthase inhibitor LNNA. Using ex vivo luminol-enhanced CL, we have also demonstrated that in sham-operated and MI animals, AM-enhanced ROS generation from activated peripheral blood leukocytes occurs over a similar time course to the depressor response to AM. Although this study was not designed to address the question of which ROS species are generated under the present experimental conditions, one possibility is that leukocyte-derived NO or a NO-derived species such as peroxynitrite could be responsible for the detected increase in the CL as the enhanced ROS generation was inhibited by LNNA and MPG. Indeed, we have shown previously that leukocyte-derived NO can increase the chemiluminescent signal in isolated porcine leukocytes by reacting with superoxide to produce peroxynitrite (Demiryürek et al., 1997). Thus we hypothesize that AM, in addition to causing NO release from the endothelium, induces NO production by leukocytes, which subsequently interacts with leukocyte-derived superoxide to contribute to the chemiluminescent signal. We have also provided evidence that AM administration results in production of peroxynitrite in the vicinity of the coronary endothelium, as immunocytochemical staining for nitrotyrosine, a stable product of peroxynitrite nitration, was enhanced within the endothelium of coronary arteries. This presumably occurs through the interaction of increased levels of NO with superoxide which is known to be released continuously from endothelial cells (reviewed in Wolin et al., 2002).

Cardiac AM gene expression and protein synthesis is rapidly induced following MI (Nagaya et al., 2000) and it has been proposed that endogenously produced AM may play a compensatory role to protect against further deterioration of pathophysiological conditions (Eto et al., 1999). In the present study in rats subjected to acute MI, a single bolus dose of AM given 5 min prior to coronary artery occlusion protected against the resultant arrhythmias by reducing the total number of VEBs (predominantly VT) and the incidence of VF. These findings provide the first evidence for an antiarrhythmic effect of AM when given exogenously prior to ischaemia and compliments previous findings that both exogenous delivery of AM (Nakamura et al., 2002; Shimosawa et al., 2002; Niu et al., 2004) and AM gene delivery (Kato et al., 2003) can reduce the injury and long-term ventricular remodelling following myocardial infarction. The finding that while the total incidence of VF was reduced by AM, mortality from this arrhythmia was not modified, provides some insight into the antiarrhythmic action of AM. In the rat, VF can spontaneously revert to sinus rhythm and drugs that are defibrillatory can reduce the incidence of terminal VF in this model (Curtis, 1994). This implies that, whatever the mechanism underlying the antiarrhythmic effect of AM, it does not include a defibrillatory effect.

We have also shown that the antiarrhythmic effects of AM were abolished by NOS inhibition, suggesting that stimulation of the NO pathway is a prerequisite factor for AM-induced cardioprotection. This is consistent with a recent study by Hamid & Baxter (2005) which demonstrated that AM-induced cardioprotection in isolated rat hearts was mediated by an NO-dependent mechanism. Although NO donors (Aitchison & Coker, 1999) or nitrovasodilators (du Toit et al., 1988) have been reported to reduce ischaemia/reperfusion-induced cellular damage in rats, they fail to protect against ischaemia-induced arrhythmias in rats (Sun & Wainwright, 1997). Furthermore, inhibition of basal production of endogenous NO with LNNA in the present studies did not modify arrhythmia severity, despite increasing arterial pressure, which is consistent with our previous studies with N(G)-nitro-L-arginine-methylester (L-NAME) (Sun & Wainwright, 1997). The ability of LNNA to block the antiarrhythmic effect of AM may point to differences between the ability of basally produced endogenous NO generated during ischaemia, and endogenous NO generated in response to pharmacological stimulation prior to ischaemia, to influence the severity of ischaemia-induced arrhythmias. In contrast, Pabla & Curtis (1995) have demonstrated that blocking NOS activity increases the incidence of reperfusion-induced VF in rat isolated hearts, implying that endogenous NO may play different roles in arrhythmia modulation depending upon the setting.

One proposed mechanism by which endogenous NO exerts cardioprotection is through the generation of ROS by interaction with superoxide, as ROS have been shown to mimic the injury-limiting effects of ischaemic preconditioning (Tritto et al., 1997) as well as to trigger anaesthetic preconditioning (Novalija et al., 2002). Similarly, low concentrations (2–5 μM) of peroxynitrite have been shown to protect against both ischaemia/reperfusion-induced arrhythmias (Altug et al., 2001) and injury (Lefer et al., 1997). In the present study, the abolition of the antiarrhythmic effect of AM by MPG supports this concept, providing the first evidence for an involvement of peroxynitrite in the antiarrhythmic effect of AM. Based on our observations in sham-operated and MI rats that nitrotyrosine was detected within the coronary endothelium following AM administration, and that this was decreased by NOS inhibition, we propose that the coronary endothelium could be a source of NO-dependent peroxynitrite formation following exogenous AM administration, which then acts as a mediator of the observed antiarrhythmic effects. The lack of nitrotyrosine in the endothelium of saline-treated rats subjected to ischaemia is most likely due to the fact that reperfusion subsequent to ischaemia is required for peroxynitrite to be generated (Liu et al., 1997).

Although we have demonstrated that ex vivo activation of peripheral blood leukocytes exposed to AM in vivo generate increased ROS, it is unlikely that this can account for the observed antiarrhythmic effect of AM. This is primarily because in vivo leukocyte activation occurs after a longer period of ischaemia than that employed in the present study and also requires reperfusion of the ischaemic tissue (Kaminski et al., 2002). This also explains why we did not see an increase in ROS production from leukocytes sampled during the ischaemic period. While enhanced ROS (possibly including peroxynitrite) production by inflammatory cells may explain the cardioprotective effects of AM observed in some studies designed to examine its effects on infarct size, the study by Hamid & Baxter (2005) was performed in the absence of circulating inflammatory cells. Thus, the role of leukocytes in the cardioprotective effect of AM as yet remains unresolved. In order to demonstrate more directly the role of ROS produced by the cardiac tissue in the antiarrhythmic action of AM, it would be necessary to perform measurement of ROS generation directly from the cardiac tissue, which we were unable to do in the present study.

Peroxynitrite has been implicated as a physiologically active toxic metabolite of NO that causes vascular and myocardial dysfunction and, as such, the ability of peroxynitrite to induce cardioprotection may seem paradoxical. Exogenous administration of peroxynitrite to crystalloid perfused hearts clearly induces detrimental effects on cardiac performance (reviewed in Ferdinandy & Schulz, 2003), whereas in vivo administration of peroxynitrite prior to ischaemia has been shown to reduce myocardial injury and adherence of leukocytes to coronary endothelium (Lefer et al., 1997; Nossuli et al., 1997). Some light has been shed on this inconsistency by studies by Ronson et al. (1999) and Ma et al. (2000), which have highlighted the difference in response to peroxynitrite-generating systems in crystalloid-perfused and blood-perfused hearts. These observations have led to the notion that the physiological effects of peroxynitrite on the myocardium are exquisitely dependent upon the physiological environment and that there is some component within the blood that reduces the toxicity of peroxynitrite. It has been proposed that peroxynitrite is cardioprotective through the ability of certain thiol-containing compounds, such as glutathione, in the blood and tissues, to convert peroxynitrite to S-nitrosothiols (Vinten-Johansen, 2000). Indeed, the detrimental effects of peroxynitrite in crystalloid-perfused hearts can be attenuated by the addition of glutathione to the perfusion solution (Nakamura et al., 2000). Thus, thiol-derived compounds formed through reaction with peroxynitrite may protect the heart by preventing the toxic accumulation of peroxynitrite. Furthermore, the generation of protective NO over a sustained period of time (Moro et al., 1995) or the stimulation of coronary vasodilatation by triggering intracellular second messenger pathways to increase cGMP (Mayer et al., 1995) may also play a role in peroxynitrite-induced cardioprotection. With respect to endogenously produced peroxynitrite, although the induction of MI and reperfusion has been associated with increased peroxynitrite formation (as demonstrated by increase nitrotyrosine staining; Liu et al., 1997), no direct causal relationship between this and cardiomyocyte damage was demonstrated. In studies to determine the importance of peroxynitrite in ischaemic preconditioning, Csonka et al. (2001) have shown that peroxynitrite levels in cardiac tissue are increased after the first cycle of ischaemic preconditioning, but after a third cycle of ischaemia, peroxynitrite levels were reduced, which led to the conclusion that peroxynitrite generated during ischaemia/reperfusion might act as a trigger for preconditioning. To our knowledge, this is the first observation that endogenously generated peroxynitrite in response to a pharmacological preconditioning stimulus may be involved in cardioprotection.

Although we have shown that AM has a NO- and peroxynitrite-dependent antiarrhythmic effect when given exogenously prior to coronary occlusion, we have not fully established the mechanism(s) underlying this action and there are some limitations to the study. First, our argument that the effect of MPG on arrhythmias is linked to an inhibition of peroxynitrite production could be strengthened by the demonstration that MPG inhibited nitrotyrosine deposition in a similar way to LNNA. However, the lack of sufficient tissue from the MPG-treated rats precluded this analysis and it would therefore be important to revisit this point in future studies. Second, there were slight differences in the incidences of VF in the controls used in the separate studies to determine the effect of AM alone (incidence 60%) and the effect of AM in the presence of LNNA and MPG (incidence 40%) on arrhythmias. This variability in VF incidence is due to the fact that these studies were performed at different times of the year, which is a frequent finding in our laboratory and is supported by evidence from both animal and human studies that there is seasonal variation in the severity of arrhythmias resulting from an ischaemic episode (Janse et al., 1998; Muller et al., 2003). However, as it is inappropriate to pool the data from the two contemporaneous control groups, this makes a direct comparison between the two studies difficult. Finally, many of the studies to determine the mechanism of the cardioprotective effect of AM have implicated a role for Akt activation, which could induce an antiapoptotic mechanism (Okumura et al., 2004) or induce phosphorylation of eNOS. This latter mechanism could be an event upstream of the NOS activation identified in the present study and further studies are therefore clearly needed to fully elucidate the receptor and the sequence of signal transduction mechanisms through which AM is cardioprotective.

Acknowledgments

Yee Hoo Looi was in receipt of an Overseas Research Scholarship (ORS) award and a University of Strathclyde PhD Studentship.

Abbreviations

- AM

adrenomedullin

- BP

blood pressure

- CL

chemiluminescence

- ECG

electrocardiogram

- HR

heart rate

- L-NAME

N(G)-nitro-L-arginine-methylester

- LNNA

N(G)-nitro-L-arginine

- MABP

mean arterial blood pressure

- MI

myocardial ischaemia

- MPG

N-mercaptopropionyl-glycine

- NO

nitric oxide

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- VEB

ventricular ectopic beat

- VF

ventricular fibrillation

- VT

ventricular tachycardia

References

- AITCHISON K., COKER S.J. Potential interactions between iloprost and SIN-1 on platelet aggregation and myocardial infarct size in vitro. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1999;374:59–69. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTUG S., DEMIRYUREK A.T., AK D., TUNGEL M., KANZIK I. Contribution of peroxynitrite to the beneficial effects of preconditioning on ischaemia-induced arrhythmias in rat isolated hearts. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2001;415:239–246. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)00843-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ALTUG S., DEMIRYUREK A.T., KANE K.A., KANZIK I. Evidence for the involvement of peroxynitrite in ischaemic preconditioning in rat isolated hearts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2000;130:125–131. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0703280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BAINES C., GOTO M., DOWNEY J. Oxygen radicals released during ischaemic preconditioning contribute to cardioprotection in the rabbit myocardium. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 1997;29:207–216. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1996.0265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BILINSKA M., MACZEWSKI M., BERESEWICZ A. Donors of nitric oxide mimic effects of ischaemic preconditioning on reperfusion induced arrhythmias in isolated rat hearts. Mol. Cell. Biochem. 1996;160–161:265–271. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4613-1279-6_34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHINI E.N., CHINI C.S., BOLLIGER C., JOUGASAKI M., GRANDE J.P., BURNETT J.C., JR, DOUSA T.P. Cytoprotective effects of adrenomedullin in glomerular cell injury: central role of cAMP signalling pathway. Kidney Int. 1997;52:917–925. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHINI E.N., CHOI E., GRANDE J.P., BURNETT J.C., DOUSA T.P. Adrenomedullin suppresses mitogenesis in rat mesangial cells via cAMP pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Comm. 1995;215:868–873. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK C., FOREMAN M.I., KANE K.A., MCDONALD F.M., PARRATT J.R. Coronary artery ligation in anaesthetized rats as a method for the production of experimental dysrhythmias and for the determination of infarct size. J. Pharmacol. Methods. 1980;3:357–368. doi: 10.1016/0160-5402(80)90077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CSONKA C., CSONT T., ONODY A., FERDINANDY P. Preconditioning decreases ischemia/reperfusion-induced peroxynitrite formation. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2001;285:1217–1219. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CURTIS M.J. Chemical defibrillation in acute myocardial ischaemia: a hypothesis. J. Basic Clin. Physiol. Pharmacol. 1994;5:1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMIRYÜREK A.T., KARAMSETTY M.R., MCPHADEN A.R., WADSWORTH R.M., KANE K.A., MACLEAN M.R. Accumulation of nitrotyrosine correlates with endothelial NO synthase in pulmonary resistance arteries during chronic hypoxia in the rat. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther. 2000;13:157–165. doi: 10.1006/pupt.2000.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEMIRYÜREK A.T., KENNEDY S., WAINWRIGHT C.L., WADSWORTH R.M., KANE K.A. Influence of nitric oxide on luminol-enhanced chemiluminescence measured from porcine-stimulated leukocytes. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;30:332–337. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DU TOIT E.F., MCCARTHY J., MIYAHIRO J., OPIE L.H., BRUNNER F. Effects of nitrovasodilators and inhibitors of nitric oxide synthase on ischaemic and reperfusion function of rat isolated hearts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1988;123:1159–1167. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ETO T., KITAMURA K., KATO J. Biological and clinical roles of adrenomedullin in circulation control and cardiovascular diseases. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 1999;26:371–380. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1681.1999.03047.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FENG C.J., KANG B., KAYE A.D., KADOWITZ P.J., NOSSAMAN B.D. L-NAME modulates responses to adrenomedullin in the hindquarters vascular bed of the rat. Life Sci. 1994;55:433–438. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00347-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FERDINANDY P., SCHULZ R. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite on muocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury and preconditioning. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2003;138:532–643. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMID S.A., BAXTER G.F. Adrenomedullin limits reperfusion injury in experimental myocardial infarction. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2005;100:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s00395-005-0538-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAYAKAWA H., HIRATA Y., KAKOKI M., SUZUKI Y., NISHIMATSU H., NAGATA D., SUZUKI E., KIKUCHI K., NAGANO T., KANGAWA K., MATSUO H., SUGIMOTO T., OMATA M. Role of nitric oxide-cGMP pathway in adrenomedullin-induced vasodilation in the rat. Hypertension. 1999;33:689–693. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.2.689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HE H., BESSHO H., FUJISAWA Y., HORIUCHI K., TOMOHIRO A., KITA T., AKI Y., KIMURA S., TAMAKI T., ABE Y. Effects of a synthetic rat adrenomedullin on regional haemodynamics in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1995;273:209–214. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)00683-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ISHIYAMA Y., KITAMURA K., ICHIKI Y., NAKAMURA S., KIDA O., KANGAWA K., ETO T. Haemodynamic effects of a novel hypotensive peptide, human adrenomedullin, in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1993;241:271–273. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(93)90214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSE M.J., OPTHOF T., KLEBER A.G. Animal models of cardiac arrhythmias. Cardiovasc. Res. 1998;39:165–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KAMINSKI K.A., BONDA T.A., KORECKI J., MUSIAL W.J. Oxidative stres and neutrophil activation – the two keystones of ischaemia/reperfusion injury. Int. J. Cardiol. 2002;86:41–59. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5273(02)00189-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO H., SHICHIRI M., MURUMO F., HIRATA Y. Adrenomedullin as an autocrine/paracrine apoptosis survival factor for rat endothelial cells. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2615–2620. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.6.5197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO J., KOBAYASHI K., ETOH T., TANAKA M., KITAMURA K., IMAMURA T., KOIWAYA Y., KANGAWA K., ETO T. Plasma adrenomedullin concentration in patients with heart-failure. J. Clin. Endocr. Metabol. 1996;81:180–183. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KATO K., YIN H., AGATA J., YOSHIDA H., CHAO L., CHAO J. Adrenomedullin gene delivery attenuates myocardial infarction apoptosis after ischaemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. 2003;285:H1506–H1514. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00270.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., KANGAWA K., KAWAMOTO M., ICHIKI Y., NAKAMURA S., MATSUO H., ETO T. Adrenomedullin: a novel hypotensive peptide isolated from human pheochromocytoma. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993a;192:553–560. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITAMURA K., SAKATA J., KANGAWA K., KOJIMA M., MATSUO H., ETO T. Cloning and characterization of cDNA encoding a precursor for human adrenomedullin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1993b;194:720–725. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFER D.J., SCALIA R., CAMPBELL B., NOSSULI T., HAYWARD R., SALAMON M., GRAYSON J., LEFER A.M. Peroxynitrite inhibits leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions and protects against ischaemia–reperfusion injury in rats. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;99:684–691. doi: 10.1172/JCI119212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU P.T., HOCK C.E., NAGELE R., WONG P.Y.K. Formation of nitric oxide, superoxide and peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia–reperfusion injury in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 1997;272:H2327–H2336. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.5.H2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MA X.-L., GAO F., LOPEZ B.L., CHRISTOPHER T.A., VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. Peroxynitrite, a two-edged sword in post-ischaemic myocardial injury – dichotomy of action in crystalloid- versus blood-perfused hearts. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2000;292:912–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAYER B., SCHRAMMEL A., KLATT P., KOESLING D., SCHMIDT K. Peroxynitrite-induced accumulation of cyclic GMP in endothelial cells and stimulation of purified soluble guanylyl cyclase. Dependence on glutathione and possible role of S-nitrosation. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:17355–17360. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORO M.A., DARLEY-USMAR V.M., LIZASOAIN I., SU Y., KNOWLES R.G., RADOMSKI M.W., MONCADA S. The formation of nitric oxide donors from peroxynitrite. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:1999–2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb16404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MULLER D., LAMPE F., WEGSCHNEIDER K., SCHULTHEISS H.B., BEHRENS S. Annual distribution of ventricular tacnycardias and ventricular fibrillation. Amer. Heart J. 2003;146:941–943. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8703(03)00426-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAGAYA N., NISHIKIMI T., YOSHIHARA F., HORIO T., MORIMOTO A., KANGAWA K. Cardiac adrenomedullin gene expression and peptide accumulation after acute myocardial infarction in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000;278:R1019–R1026. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.2000.278.4.R1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA M., THOURANI V.H., RONSON R.S., VELEZ D., MA X.-L., KATZMARK S., ROBINSON J., SCHMARKET L.S., ZHAO Z.-Q., WANG N.-P., GUYTON R.A., VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. Glutathione reverses endothelial damage from peroxynitrite, the by-product of nitric oxide degradation, in crystalloid cardioplegia. Circulation. 2000;102 Suppl 3:III332–III338. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.suppl_3.iii-332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NAKAMURA R., KATO J., KITAMURA K., ONITSUKA H., IMAMURA T., MARUTSUKA K., ASADA Y., KANGAWA K., ETO T. Beneficial effects of adrenomedullin on left ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in rats. Cardiovasc. Res. 2002;56:373–380. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00594-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NIU P., SHINDO T., IWATA H., IIMURO S., TAKEDA N., ZHANG Y., EBIHARA A., SUEMATSU Y., KANGAWA K., HIRATA Y., NAGAI R. Protective effects of endogenous adrenomedullin on cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and renal damage. Circulation. 2004;109:1–6. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118466.47982.CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSSAMAN B.D., FENG C.J., KAYE A.D., DEWITT B., COY D.H., MURPHY W.A., KADOWITZ P.J. Pulmonary vasodilator responses to adrenomedullin are reduced by NOS inhibitors in rats but not in cats. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;270:L782–L789. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1996.270.5.L782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSSULI T.O., HAYWARD R., JENSEN D., SCALIA R., LEFER A.M. Mechanisms of cardioprotection by peroxynitrite in myocardial ischaemia and reperfusion. Am. J. Physiol. 1998;275:H509–H519. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1998.275.2.H509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOSSULI T.O., HAYWARD R., SCALIA R., LEFER A.M. Peroxynitrite reduces myocardial infarct size and preserves coronary endothelium after ischaemia and reperfusion in cats. Circulation. 1997;96:2317–2324. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.7.2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOVALIJA E., VARADARAJAN S.G., CAMARA A.K., AN J., CHEN Q., RIESS M.L., HOGG N., STOWE D.F. Anesthetic preconditioning: triggering role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in isolated heart. Am. J. Physiol. 2002;283:H44–H52. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01056.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OKUMURA H., NAGAYA N., ITOH T., OKANO I., HINO J., MORI K., TSUKAMOTO Y., ISHIBASHI-UEDA H., MIWA S., TAMBARA K., TOYOKUNI S., YUTANI C., KANGAWA K. Adrenomedullin infusion attenuates myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury through the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. Circulation. 2004;109:242–248. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109214.30211.7C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PABLA R., BLAND-WARD P., MOORE P.K., CURTIS M.J. An endogenous protectant effect of cardiac cyclic GMP against reperfusion ventricular fibrillation in the rat heart. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2923–2930. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15946.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PABLA R., CURTIS M.J. Effect of NO modulation on cardiac arrhythmias in the rat isolated heart. Circ. Res. 1995;77:984–992. doi: 10.1161/01.res.77.5.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- RONSON R.S., NAKAMURA M., VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. The cardiovascular effects and implications of peroxynitrite. Cardiovasc. Res. 1999;44:47–59. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00184-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SHIMOSAWA T., SHIBAGAKI Y., ISHIBASHI K., KITAMURA K., KANGAWA K., KATO S., ANDO K., FUJITA T. Adreomedullin, an endogenous peptide, counteracts cardiovascular damage. Circulation. 2002;105:106–111. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUN W., WAINWRIGHT C.L. The role of nitric oxide in modulating ischaemia-induced arrhythmias in rats. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1997;29:554–562. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199704000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TRITTO I., D'ANDREA D., ERAMO N., SCOGNAMIGLIO A., DE SIMONE C., VIOLANTE A., ESPOSITO A., CHIARIELLO M., AMBROSIO G. Oxygen radicals can induce preconditioning in rabbit hearts. Circ. Res. 1997;80:743–748. doi: 10.1161/01.res.80.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VINTEN-JOHANSEN J. Physiological effects of peroxynitrite: potential products of the environment. Circ. Res. 2000;87:170–172. doi: 10.1161/01.res.87.3.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WALKER M.J.A., CURTIS M.J., HEARSE D.J., CAMPBELL R.W.F., JANSE M.J., YELLON D.M., COBBE S.M., COKER S.J., HARNESS J.B., HARRON D.W.G., HIGGINS A.J., JULIAN D.G., LAB M.J., MANNING A.S., NORTHOVER B.J., PARRATT J.P., RIEMERSMA R.A., RIVA E., RUSSELL D.C., SHERIDAN D.J., WINSLOW E., WOODWARD B. The Lambeth Conventions: guidelines for the study of arrhythmias in ischaemia, infarction, and reperfusion. Cardiovasc. Res. 1988;22:447–455. doi: 10.1093/cvr/22.7.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WOLIN M.S., GUPTE S.A., OECKLER R.A. Superoxide in the vascular system. J. Vasc. Res. 2002;39:191–207. doi: 10.1159/000063685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG B.C., LIPPTON H., GUMUSEL B., HYMAN A., MEHTA J.L. Adrenomedullin dilates rat pulmonary artery rings during hypoxia: role of nitric oxide and vascular prostaglandins. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 1996;28:458–462. doi: 10.1097/00005344-199609000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]