Abstract

A-349821 is a selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist. Herein, binding of the novel non-imidazole H3 receptor radioligand [3H]A-349821 to membranes expressing native or recombinant H3 receptors from rat or human sources was characterized and compared with the binding of the agonist [3H]N-α-methylhistamine ([3H]NαMH).

[3H]A-349821 bound with high affinity and specificity to an apparent single class of saturable sites and recognized human H3 receptors with 10-fold higher affinity compared to rat H3 receptors. [3H]A-349821 detected larger populations of receptors compared to [3H]NαMH.

Displacement of [3H]A-349821 binding by H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists was monophasic, suggesting recognition of a single binding site, while that of H3 receptor agonists was biphasic, suggesting recognition of both high- and low-affinity H3 receptor sites.

pKi values of high-affinity binding sites for H3 receptor competitors utilizing [3H]A-349821 were highly correlated with pKi values obtained with [3H]NαMH, consistent with labelling of H3 receptors by [3H]A-349821.

Unlike assays utilizing [3H]NαMH, addition of GDP had no effect on saturation parameters measured with [3H]A-349821, while displacement of [3H]A-349821 binding by the H3 receptor agonist histamine was sensitive to GDP.

In conclusion, [3H]A-349821 labels interconvertible high- and low-affinity states of the H3 receptor, and displays improved selectivity over imidazole-containing H3 receptor antagonist radioligands. [3H]A-349821 competition studies showed significant differences in the proportions and potencies of high- and low-affinity sites across species, providing new information about the fundamental pharmacological nature of H3 receptors.

Keywords: Histamine; radioligand binding; H3-receptor binding; radiolabelled H3-receptor antagonist; radiolabelled H3-receptor inverse agonist; [3H]A-349821; guanine nucleotide shift; G-protein, G-protein-coupled receptor

Introduction

To date, a majority of histamine H3 receptor-binding studies have relied on the H3 receptor-selective agonists [3H]RαMH and [3H]NαMH as radiolabels (van der Goot & Timmerman, 2000). While having high selectivity and specific binding along with favorable signal to noise ratios, binding of these agonist radioligands to H3 receptors is sensitive to guanine nucleotides, suggesting that H3 receptor agonist radioligands recognize both high- and low-affinity receptor sites (Arrang et al., 1990; West et al., 1990a; Kilpatrick & Michel, 1991; Clark et al., 1993). This makes characterization of H3 receptors difficult because of assay-dependent variables, such as membrane preparation procedures (Childers & Lariviere, 1984; Kim & Neubig, 1987) and ionic composition of assay buffers that can alter receptor–G-protein interactions and affect the apparent affinity state of the receptor (Hamblin & Creese, 1982; Kilpatrick & Michel, 1991; Parkinson & Fredholm, 1992). Several radiolabelled H3-antagonists have been described previously, such as [3H]S-methylthioperamide, [125I]iodophenpropit, [125I]iodoproxyfan, [3H]thioperamide, [3H]GR168320 and [3H]clobenpropit (Jansen et al., 1992; Ligneau et al., 1994; Yanai et al., 1994; Alves-Rodrigues et al., 1996; Brown et al., 1996; Harper et al., 1999), but they have not been widely used. This is attributable to a variety of limiting factors, such as low specific activity, poor H3 receptor specificity, equivocal functional properties or lack of commercial availability. Moreover, all of the previously referenced H3 receptor antagonist radiolabels contain an imidazole moiety, which may be responsible for off-target binding to 5-HT3 receptors, H4 receptors and cytochrome P450 isoenzymes (Labella et al., 1992; Leurs et al., 1995; Schlicker et al., 1995; Alves-Rodrigues et al., 1996; Harper et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2002; Esbenshade et al., 2005a; Kitbunnadaj et al., 2005). More recently, we described the first non-imidazole, H3 receptor antagonist, [3H]A-317920 (Esbenshade et al., 2005b; Yao et al., 2005). [3H]A-317920 is a highly selective and potent radiolabel useful for detection and characterization of recombinant rat H3 receptors expressed in C6 cells, a rat glioma cell line, or native H3 receptors expressed in rat cortical tissue. However, this radioligand does not recognize human H3 receptors with high affinity, and as such has limited utility.

Subsequent medicinal chemistry efforts revealed a novel non-imidazole H3 receptor ligand, A-349821, having high potency and selectivity for both rat and human H3 receptors in competition-binding assays and potent antagonist activity in a variety of in vitro functional assays as well as H3 receptor-mediated in vivo models (Esbenshade et al., 2004). A-349821 also displayed highly efficacious and potent inverse agonist properties in [35S]GTPγS-binding assays across species (Esbenshade et al., 2004). Competition-binding studies carried out with ∼75 G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) and ligand-gated ion channels showed minimal crossreactivity (IC50>1 μM), with weak affinity (IC50=250 nM) observed for α2c adrenergic receptors (Esbenshade et al., 2004). With these promising binding and pharmacological properties, [3H]A-349821 was prepared and evaluated as a radiolabel for the detection of H3 receptors in membranes expressing recombinant or native rat or human H3 receptors. Like the agonist radioligand [3H]NαMH, [3H]A-349821 exhibited specific and saturable binding to tissues or cell lines expressing either rat or human H3 receptors. Detailed competition-binding studies using a large panel of H3 receptor ligands were performed to compare the pharmacology of [3H]A-349821 with that of [3H]NαMH. The effects of guanosine 5′-diphosphate (GDP) on binding were determined to investigate the contribution of low- and high-affinity binding states to the observed pharmacology. Herein, we describe the use of [3H]A-349821 as the first non-imidazole radioligand for the highly specific detection and characterization of both rat and human H3 receptors.

Methods

Synthesis of [3H]A-349821

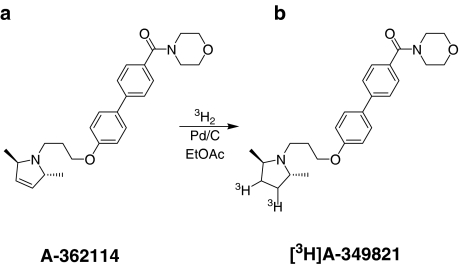

A-362114 ({4′-[3-(2R,5R)-dimethyl-2,5-dihydro-pyrrol-1-yl)-propoxy]-biphenyl-4-yl}-morpholin-4-yl-methanone) (10 mg, 0.024 mmol) was dissolved in ethyl acetate (2 ml). Palladium on carbon (10%, 11 mg) was added and the mixture was degassed by freeze–pump–thaw and stirred under an atmosphere of tritium gas (0.042 mmol, 2.5 Ci) at room temperature for 2.5 h. The catalyst was filtered and labile tritium was removed by three evaporations of methanol to yield 362 mCi of crude [3H]A-349821 ([dimethylpyrrolidinyl-3,4-3H2]{4′-[3-(2R,5R-dimethyl-pyrrolidin-1-yl)-propoxy]-biphenyl-4-yl}-morpholin-4-yl-methanone) (for chemical structures, see Figure 1). One-fifth of the product was purified by reversed-phase HPLC, using a 20 × 250 mm BHK ODS-W/S column (BHK Laboratories, Chicago, IL, U.S.A.) eluted at 16 ml min−1 with 43% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. The major UV peak (254 nm) was collected in four fractions and the two major fractions were combined and lyophilized to give a white solid (50 mCi). HPLC analysis showed 84% radiochemical purity, so a second purification using the same system, but with 30% acetonitrile, ensued. The desired product eluted at 34–38 min providing 20 mCi at >99% radiochemical purity by HPLC. The identity was established by HPLC retention time, co-injecting with authentic A-349821. The specific activity was determined to be 22 Ci mmol−1 by measuring the mass concentration from an HPLC standard curve followed by liquid scintillation counting to determine the radioactivity concentration.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of the precursor, A-362114 (a) and the radiolabelled product ([3H]A-349821 ([dimethylpyrrolidinyl-3,4-3H2]{4′-[3-(2R,5R-dimethyl-pyrrolidin-l-yl)-propoxyl-biphenyl-4-yl}-morpholin-4-yl-methanone) (b).

Preparation of membranes from rat and human cortices and C6 cells expressing recombinant rat and human H3 receptors

Cortices were obtained from Sprague–Dawley rats (Pelfreez, Rogers, AR, U.S.A.). Human cortical tissue was obtained from Analytical Biological Sciences (Wilmington, DE, U.S.A.). C6 cell lines stably expressing full-length (445 A.A.) recombinant human or rat H3 receptors were generated and cultured as described previously (Yao et al., 2003). Cortical tissues or C6 cells expressing recombinant H3 receptors were homogenized in ice-cold Tris–EDTA buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) containing protease inhibitors (2 μg ml−1 aprotinin, 1 mM benzamidine, 2 μg ml−1 leupeptin and 1 μg ml−1 pepstatin; Sigma, St Louis, MO, U.S.A.) using an Ultra-Turrax T25 polytron (Janke & Kunkel GMBH & Co. KG, Germany) at maximum setting (24,000 r.p.m.) for 2 × 10 s. Homogenates were centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 20 min. Membrane pellets were further processed by repeating the above homogenization and centrifugation steps. Final membrane preparations were obtained by re-homogenizing pellets by polytron in 6.25 ml g−1 (volume/wet pellet weight) of ice-cold Tris–EDTA buffer. Membranes were divided into aliquots, flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C until use. Protein concentrations were determined using the BCA method with bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a standard (Smith et al., 1985).

[3H]NαMH and [3H]A-349821 – saturation studies

Binding assays were conducted as described previously (Esbenshade & Hancock, 2000). Briefly, dilutions of radioligands and competitors were made with Tris–EDTA buffer (50 mM Tris, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 at room temperature). Tris–EDTA buffer with 0.2% BSA was included for all studies using [3H]A-349821 to effectively prevent adsorption to labware surfaces. Membrane preparations were thawed and homogenized (polytron) in various volumes of Tris–EDTA buffer to give protein concentrations of ∼70, ∼60, ∼600, and ∼1000 μg ml−1 for membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors, and from rat and human cortices, respectively. Assay components were combined in 96-well BioBlocks™ in duplicate to give a final volume of 0.5 ml, or for recombinant human, 1 ml. Membrane preparations were incubated with various concentrations of [3H]NαMH (∼0.1–6 nM) or [3H]A-349821 (∼0.01 to ∼6 nM) at 25°C for 30 or 60 min, respectively. Nonspecific binding was defined by the presence of 10 μM thioperamide. Binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through Whatman GF/B filters pre-soaked in 0.3% polyethylenimine in Tris buffer (50 mM Tris, pH 7.4 at 4°C); filters were washed (4 × 2 ml) with ice-cold Tris buffer using a Brandel Cell Harvester (Brandel Inc., Gaithersburg, MD, U.S.A.). Filters were transferred into scintillation vials, Ultima-Gold™ scintillant (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA, U.S.A.) was added, and after 2 h the bound radioactivity was determined by counting for 3 min in a Packard liquid scintillation counter.

[3H]A-349821 – kinetic studies

Kinetic studies were performed with ∼4 nM [3H]A-349821 (membranes from C6 cells stably expressing the recombinant rat H3 receptor or rat cortices) or ∼1 nM [3H]A-349821 (membranes from C6 cells stably expressing the recombinant human H3 receptor) as described above with minor modifications. To determine the observed association rates, triplicate membrane samples were incubated with [3H]A-349821 for increasing time intervals ranging from 0.33 to 90 min. Nonspecific binding for each time point was defined by the presence of 10 μM thioperamide. For dissociation kinetic studies, the same membrane preparation was incubated with [3H]A-349821 1 h before dissociation was initiated by exposure to 10 μM thioperamide for increasing time intervals ranging from 1 to 120 min. Filtration and counting methods were as described above.

[3H]NαMH and [3H]A-349821 – competition studies

Competition-binding assays were performed with minor modifications to the binding assays described above. Membranes were incubated with 0.5 nM [3H]NαMH or 1.5 nM [3H]A-349821 (membranes from C6 cells stably expressing rat H3 receptors or rat cortices), or 0.5 nM [3H]A-349821 (membranes from C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors) in the presence or absence of competitors. Nonspecific binding was defined by the presence of 10 μM thioperamide. Binding reactions were carried out for 30 min ([3H]NαMH) or 60 min ([3H]A-349821) at 25°C. To study the effects of GDP on binding, assays were carried out in the absence or presence of 100 μM GDP with an incubation time of 60 min for all experiments. For membranes from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors, binding reactions were terminated by rapid filtration through 96-well GF/B-Unifilters™ presoaked in 0.3% polyethylenimine in Tris buffer, which were washed (4 × 2 ml) with ice-cold Tris buffer using a Packard Unifilter harvester. Filters were allowed to dry, PerkinElmer MICROSCINT™ 20 scintillant was added (40 μl well−1) and bound radioactivity was determined by counting in a Packard Topcount scintillation counter for 3 min. Binding assays with membranes from rat cortices were terminated and processed using the Brandell harvester, as described above.

Data analysis

KD values from saturation-binding assays were evaluated by one-site and two-site binding methods using Prism™ software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA, U.S.A.). KD values reported are based on comparison of one-site and two-site curve fits with an F-test in which the sum-of-squares and degrees of freedom are compared for each fit (significance at a 95% confidence limit).

Observed rate constants (kob) or dissociation rate constants (koff) were analyzed with Prism™ software using one-phase and two-phase exponential association or one-phase and two-phase exponential decay parameters. Rate constant values reported are based on comparison of one-phase and two-phase curve fits with an F-test in which the sum of squares and degrees of freedom are compared for each fit (significance at a 95% confidence limit). Association rate constants (kon) were defined as (kob−koff)/[radioligand] and dissociation constants (KD) were defined as koff/kon.

Competition data were analyzed with Prism™ software using both one-site and two-site competition parameters. The number of binding sites reported is based on comparison of one-site and two-site curve fits with an F-test in which the sum of squares and degrees of freedom are compared for each fit (significance at a 95% confidence limit). IC50 values were converted to Ki values using the generalized Cheng–Prussoff equation (Cheng & Prusoff, 1973; Leff & Dougall, 1993). The paired t-test (two-tailed) with significance determined at the 95% confidence interval (P<0.05) was used for all other statistical comparisons.

Drugs and chemicals

Histamine and clobenpropit were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St Louis, MO, U.S.A.). (N)-α-methylhistamine (NαMH), (R)-α-methylhistamine (RαMH), (S)-α-methylhistamine (SαMH), imetit, immipep, iodophenpropit, and thioperamide were purchased from Tocris-Cookson (Ellisville, MO, U.S.A.). Ciproxifan, proxyfan, and GT-2331 ((1S, 2S)-(+)-4-[2-(5,5-dimethyl-hex-1-ynyl)-cyclopropyl]-1H-imidazole) (Liu et al., 2004) were synthesized at Abbott Laboratories. Nonlabelled A-349821 ({4′-[3-(2R,5R-dimethyl-pyrrolidin-1-yl)-propoxy]-biphenyl-4-yl}-morpholin-4-yl-methanone) and other A-compounds were prepared at Abbott laboratories as described previously (Faghih et al., 2002, 2003a, 2003b; Turner et al., 2003). Radiolabelled [3H]NαMH was purchased from Perkin-Elmer Life Sciences (Boston, MA, U.S.A.). Aprotinin, leupeptin, and pepstatin were purchased from Roche Molecular Biochemicals (Indianapolis, IN, U.S.A.). BSA (fatty acid free, fraction V) was from ICN Biomedicals (Aurora, OH, U.S.A.). Dulbeco's modified Eagle's cell culture medium, hygromycin B, and lipofectamine 2000 reagent were obtained from Invitrogen/LifeTech (Grand Island, NY, U.S.A.). The rat C6 glioma cell line was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Rockville, MD, U.S.A.).

Results

Saturation analysis: [3H]A-349821 and [3H]NαMH

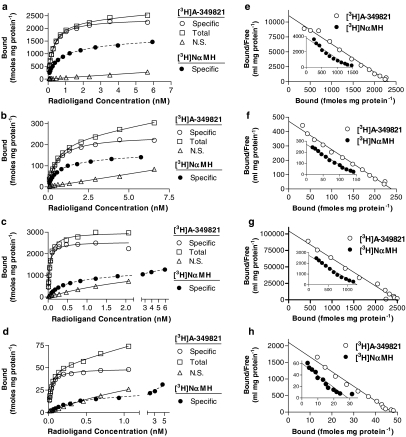

Saturable specific binding of [3H]A-349821 (for chemical structure, see Figure 1) was observed using membranes from clonal cell lines stably expressing recombinant rat or human H3 receptors and in membranes prepared from rat and human cortices (Figures 2a–d). Nonspecific binding, at [3H]A-349821 concentrations equivalent to the KD, were 1.7, 4.3, 8.3, and 9.2% for membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors, and rat and human cortices, respectively. Individual plots of specific binding versus [3H]A-349821 concentrations were, in all cases, best fit by the one-site equation over the concentration range of [3H]A-349821 tested. Scatchard plots appeared linear, also consistent with binding to a single site over the concentration range of [3H]A-349821 tested (Figure 2e–h). Calculated pKD values for [3H]A-349821 binding to membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat H3 receptors and rat cortices were 9.75 and 9.32, respectively, while somewhat higher pKD values were obtained for membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors and human cortices (10.54 and 10.50, respectively), showing that [3H]A-349821 labels recombinant and native rat and human H3 receptors with high affinity (Table 1). Estimated Bmax values were 2190, 2240, 227, and 46.6 fmol mg protein−1 for membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors and rat and human cortices, respectively. Parallel saturation assays were conducted with the H3 receptor agonist radioligand, [3H]NαMH (Figure 2a–d). Analysis of specific binding versus [3H]NαMH concentration showed a preference for curve fitting by the two-site equation, although the maximal concentrations of [3H]NαMH tested were not sufficient to adequately describe the low-affinity site. Scatchard transformations tended to deviate from linearity, consistent with the presence of both high- and low-affinity binding sites (Figure 2e–h, insets). Higher [3H]NαMH concentrations were not tested because of poor signal to noise ratios. Due to this limitation, binding parameters for the low-affinity component were ill-defined and only results for the one-site analysis of the saturation data are reported (Table 1). In contrast to [3H]A-349821, [3H]NαMH bound with similar affinity to all membrane preparations, giving pKD values ranging from 9.19 to 9.31 (Table 1). Estimated Bmax values were 1300, 1170, 140, and 29.8 fmol mg protein−1 for membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors and rat and human cortices, respectively, showing that, over the concentration range tested, [3H]NαMH labelled a significantly lower number of receptor sites (52–64%) compared with [3H]A-349821 (Table 1 and Figure 2a–h). Specific binding of [3H]A-349821 was not observed in membranes prepared from untransfected C6 cells, in membranes expressing human H4 receptors, human α2c adrenoceptors, or human 5-HT3 receptors using concentrations up to ∼6 nM (data not shown). Specificity of [3H]A-349821 at H3 receptors was also demonstrated since chlorpheniramine and ranitidine (H1 and H2 receptor ligands, respectively) had negligible affinity (pKi<5) in competition-binding studies with [3H]A-349821 (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Representative saturation curves from a total of four experiments each for binding of either [3H]A-349821 (solid lines) or [3H]NαMH (dashed lines) to sites in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors (a), cortical rat H3 receptors (b), recombinant human H3 receptors (c), or cortical human H3 receptors (d). Panels e–h are Scatchard transformation plots of panels a–d, respectively. For [3H]A-349821 saturation studies, ∼18, ∼150, ∼15, and 250 μg of membrane protein from membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors, cortical rat H3 receptors, recombinant human H3 receptors, or cortical human H3 receptors, respectively, were incubated for 60 min at 25°C, in total volumes of 0.5 or 1 ml (recombinant human), with various concentrations of [3H]A-349821 in combination with buffer (total binding) or 10 μM thioperamide (nonspecific binding). [3H]NαMH saturation-binding experiments were carried out similarly, but with a 30-min incubation time. All determinations were from duplicate tubes. Saturation-binding curves were analyzed by the one-site binding hyperbolic fit method using Prism software.

Table 1.

[3H]A-349821 and [3H]NαMH saturation-binding parameters from binding to rat or human H3 receptors in the absence and presence of 100 μM GDP

| |

|

[3H]A-349821 |

[3H]NαMH |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDP | pKD | Bmax (fmol mg protein−1) | pKD | Bmax (fmol mg protein−1) | |

| Rat H3 |

− |

9.75±0.12 |

2190±100 |

9.31±0.02 |

1300±130a |

| |

+ |

9.69±0.17 |

2350±70 |

8.59±0.02b |

1140±40a |

| Rat cortex |

− |

9.32±0.11 |

227±24 |

9.19±0.01 |

140±7a |

| |

+ |

9.39±0.05 |

224±15 |

8.98±0.02b |

119±4a,c |

| Human H3 |

− |

10.54±0.06 |

2240±190 |

9.29±0.03 |

1170±80a |

| |

+ |

10.59±0.06 |

2450±190 |

8.55±0.04b |

1160±70a |

| Human cortex |

− |

10.50±0.02 |

46.6±1.8 |

9.19±0.07 |

29.8±1.6a |

| + | 10.49±0.02 | 48.6±2.0 | 8.96±0.03b | 27.3±0.9a | |

Mean pKD (−log dissociation constant) values and Bmax (maximal binding density) were calculated from saturation analysis of [3H]A-349821 (0.01–6 nM) and [3H]NαMH (0.1–6 nM) binding to rat or human H3 receptors. Data are the mean±s.e.m. of four experiments conducted with duplicate determinations.

Significance of lower Bmax values for [3H]NαMH versus [3H]A-349821 (P<0.05).

Significance of lower pKD values with the same radiolabel in the presence of GDP compared to its absence (P<0.05).

Significance of lower Bmax values in the presence of GDP compared to its absence (P<0.05).

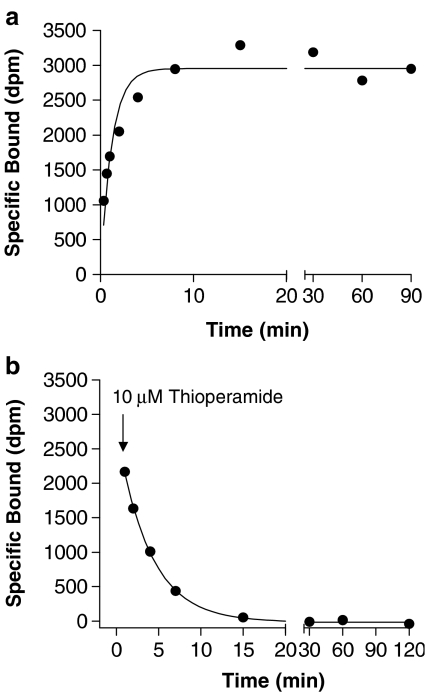

Kinetic studies: [3H]A-349821

Association and dissociation rate profiles were measured using concentrations of [3H]A-349821 equal to ∼5 nM for membranes from C6 cells or cortices expressing rat H3 receptors or ∼1 nM for membranes from C6 cells expressing human H3 receptors. These concentrations of radioligand were selected to give high receptor occupancy and to maximize signals, particularly at early time points. Due to low H3 receptor expression levels in human cortices and limited availability, kinetic studies were not carried out with these tissues. Specific binding of [3H]A-349821 in membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing rat H3 receptors was extremely rapid, achieving equilibrium within 10 min, while displacement of [3H]A-349821 by 10 μM thioperamide was rapid and virtually complete within 15 min (Figure 3). Association and dissociation rate data appeared to be monophasic, consistent with binding to a single site. Rate data for membranes prepared from rat cortices and C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors were similar in this regard (data not shown). Kinetic rate and dissociation constants (kon, koff) are summarized in Table 2. Mean rates for membranes from C6 cells expressing rat H3 receptors and rat cortices were similar (kon=1.79 and 0.80 min−1 nM−1, respectively; koff=0.38 and 0.41 min−1, respectively), while the association rate determined in membranes from C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors was markedly faster (kon=3.48 min−1 nM−1) and the dissociation rate was conversely slower (koff=0.07 min−1). As a result, the dissociation constants for [3H]A-349821 calculated using kon and koff values revealed lower affinity values in membranes from C6 cells expressing rat H3 receptors and rat cortices (pKD(Kinetic)=9.67 and 9.29, respectively) compared to membranes from C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors (pKD(Kinetic)=10.7). Kinetic dissociation constant values were similar to those determined by saturation-binding analyses (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Representative association–dissociation plots from a total of four experiments for specific binding of [3H]A-349821 to membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors. The association rate experiment was performed by incubating [3H]A-349821 (125 μl; 4 nM final concentration) for increasing times (0.33–90 min) in triplicate tubes containing membranes (250 μl; 0.03 mg ml−1 protein final), 100 μl of buffer and 25 μl of buffer or thioperamide (10 μM final concentration) to define total and nonspecific binding, respectively (a). The dissociation rate experiment was performed by incubating [3H]A-349821 (125 μl; 2 nM final concentration) for 60 min in tubes containing membranes (250 μl; 0.03 mg ml−1 protein final), 125 μl of buffer in one set of triplicate tubes to define total binding, and 100 μl of buffer and 25 μl of thioperamide (10 μM final concentration) in another set of triplicate tubes to define nonspecific binding. At this time, 25 μl of 10 μM thioperamide were added to the total binding tubes, and binding was measured over increasing times (1–120 min) (b). All experiments were carried out at 25°C in triplicate tubes. Association and dissociation rates were estimated using the ‘one-phase exponential' and ‘one-phase exponential decay' equations, respectively, using Prism software.

Table 2.

Kinetic analysis of [3H]A-349821 binding to membranes prepared from C6 cells stably expressing recombinant rat or human H3 receptors and rat cortices

| kon (min−1 nM−1) | koff (min−1) | pKD (kinetic) | pKD (saturation)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rat H3 |

1.79±0.23 |

0.38±0.03 |

9.67±0.09 |

9.75±0.12 |

| Rat cortex |

0.80±0.16 |

0.41±0.09 |

9.29±0.09 |

9.32±0.11 |

| Human H3 | 3.48±0.67 | 0.07±0.02 | 10.7±0.1 | 10.5±0.1 |

For comparison, pKD values from Table 1 are included (N=4).

Competition studies: [3H]A-349821 and [3H]NαMH

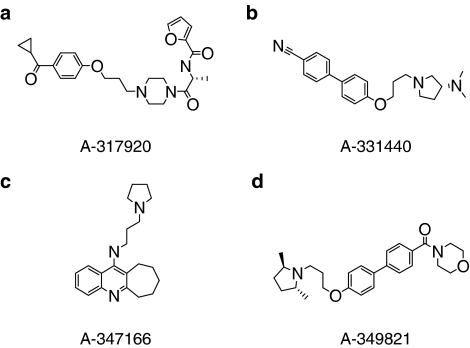

A panel of reference H3 receptor ligands, including previously described H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists that represent three lead chemical series (for chemical structures, see Figure 4) developed by Abbott Laboratories (Table 3 and Figure 5), as well as a large panel of lead series analogs (Table 4), were assessed for their ability to compete with [3H]A-349821 binding to membranes prepared from C6 cells expressing recombinant rat or human H3 receptors or from rat cortices. Individual competition curves for H3 receptor ligands previously characterized as full agonists (histamine, RαMH, NαMH, SαMH, immepip, and imetit) were biphasic and best described by two-site curve fits (Figure 5a–c and Table 3). Individual competition curves for proxyfan, an H3 receptor ligand having either agonist or antagonist functional properties depending on the assay system (Morisset et al., 2000; Gbahou et al., 2003; Krueger et al., 2005), were best described by two-site curve fits in all experiments performed with membranes from C6 cells stably expressing human H3 receptors. However, a mixture of one- or two-site curve fits was observed in individual experiments performed using membranes prepared from C6 cells expressing rat H3 receptors, while the combined competition curves were best described by two-site curve fits (Table 3 and Figure 5d–f). Varied curve fitting was also observed in individual competition curves for GT-2331, a compound having mixed functional properties similar to proxyfan (Wulff et al., 2002; Krueger et al., 2005), while combined competition curves were overall best described by two-site curve fits for membranes from C6 cells stably expressing rat or human H3 receptors, but one site for membranes from rat cortices (Table 3 and Figure 5d–f). For compounds best described by two-site curve fits, the average percentages of high-affinity H3 receptor sites were 53, 46, and 38% in membranes prepared from C6 cells expressing rat H3 receptors, rat cortices, and membranes prepared from C6 cells expressing human H3 receptors, respectively (Table 3).

Figure 4.

Structures for lead compounds representing three chemical series for the analogues listed in Table 4: the piperazine, A-317920 (a); the biaryl, A-331440 (b); the tricyclic, A-347166 (c); and the biaryl, A-349821 (d).

Table 3.

Parameters for multiple data sets from competition experiments using [3H]A-349821 or [3H]NαMH in membranes expressing rat or human H3 receptors

| |

[3H]A-349821 |

[3H]NαMH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Compound |

Rat H3 |

Rat Cortex |

Human H3 |

Rat H3 |

Rat Cortex |

Human H3 |

| |

pKi (F) |

pKi (F) |

pKi (F) |

pKi |

pKi |

pKi |

| [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | |

| Histamine |

8.25±0.18 (57%) |

8.34±0.20 (51%) |

8.21±0.14 (41%) |

8.56±0.02 |

8.42±0.02 |

8.57±0.01 |

| (ID=1) |

6.60±0.26 (43%) |

6.83±0.11 (49%) |

6.19±0.41 (59%) |

[0.94±0.01] |

[0.95±0.01] |

[0.95±0.01] |

| RαMH |

9.14±0.43 (53%) |

9.11±0.24 (43%) |

9.10±0.09 (37%) |

9.29±0.15 |

8.79±0.08 |

9.28±0.06 |

| (ID=2) |

7.40±0.42 (47%) |

7.73±0.13 (57%) |

7.13±0.10 (63%) |

[0.91±0.05] |

[0.93±0.06] |

[0.92±0.03] |

| NαMH |

9.58±0.66 (52%) |

9.49±0.13 (48%) |

9.23±0.14 (38%) |

9.50±0.09 |

8.98±0.11 |

9.48±0.04 |

| (ID=3) |

7.58±0.36 (48%) |

7.93±0.08 (52%) |

7.16±0.08 (62%) |

[0.84±0.04] |

[0.88±0.04] |

[0.94±0.03] |

| SαMH |

7.69±0.37 (38%) |

7.49±0.16 (54%) |

8.39±0.26 (30%) |

7.72±0.14 |

7.49±0.08 |

8.15±0.05 |

| (ID=4) |

6.24±0.21 (62%) |

6.03±0.18 (46%) |

6.13±0.16 (70%) |

[1.04±0.04] |

[0.93±0.04] |

[0.83±0.05] |

| Immepip |

9.67±0.29 (59%) |

9.99±0.26 (46%) |

9.54±0.12 (43%) |

9.93±0.06 |

9.29±0.15 |

9.83±0.03 |

| (ID=5) |

8.10±0.78 (41%) |

8.43±0.26 (54%) |

7.84±0.10 (57%) |

[1.05±0.06] |

[1.15±0.21] |

[1.05±0.05] |

| Imetit |

9.84±0.26 (53%) |

10.1±0.1 (40%) |

9.44±0.16 (35%) |

10.1±0.1 |

9.53±0.09 |

9.59±0.09 |

| (ID=6) |

8.23±0.20 (47%) |

8.68±0.09 (60%) |

7.65±0.05 (65%) |

[0.95±0.05] |

[0.96±0.04] |

[1.00±0.03] |

| Proxyfan |

8.40 (39%)a |

8.21 (73%)a |

8.26±0.14 (32%) |

8.62±0.10 |

8.51±0.05 |

8.35±0.06 |

| (ID=7) |

7.29 (61%)a |

7.37 (27%)a |

6.57±0.08 (68%) |

[0.88±0.04] |

[0.89±0.03] |

[0.95±0.04] |

| GT-2331 |

9.95 (38%)a |

9.22±0.13 |

7.96±0.15 (32%) |

10.0±0.1 |

9.63±0.06 |

8.39±0.07 |

| (ID=8) |

9.14 (62%)a |

[1.27±0.06] |

6.63±0.04 (68%) |

[1.03±0.04] |

[1.04±0.03] |

[1.03±0.02] |

| Clobenpropit |

10.2±0.1 |

10.0±0.2 |

9.91±0.30 |

9.82±007 |

9.45±0.08 |

9.47±0.04 |

| (ID=9) |

[1.29±0.16] |

[1.21±0.03] |

[1.05±0.11] |

[1.08±0.03] |

[0.98±0.03] |

[1.01±0.03] |

| Thioperamide |

8.74±0.22 |

8.43±0.23 |

7.54±0.21 |

8.63±0.05 |

8.20±0.07 |

7.24±0.07 |

| (ID=10) |

[0.95±0.06] |

[1.12±0.02] |

[1.00±0.11] |

[0.81±0.03] |

[0.89±0.03] |

[0.90±0.03] |

| Ciproxifan |

9.53±0.41 |

9.17±0.35 |

7.21±0.36 |

9.38±0.07 |

9.22±0.05 |

7.20±0.04 |

| (ID=11) |

[1.15±0.01] |

[1.12±0.06] |

[0.80±0.12] |

[0.90±0.02] |

[0.89±0.03] |

[0.84±0.03] |

| Iodophenpropit |

10.1±0.1 |

9.69±0.05 |

9.61±0.23 |

9.83±0.08 |

9.39±0.08 |

9.14±0.05 |

| (ID=12) |

[1.33±0.03] |

[1.16±0.02] |

[1.01±0.06] |

[1.03±0.08] |

[1.06±0.07] |

[0.92±0.04] |

| A-317920b |

9.95±0.31 |

9.31±0.24 |

7.51±0.31 |

9.24±0.08 |

9.13±0.04 |

7.02±0.04 |

| (ID=13) |

[1.00±0.05] |

[1.20±0.02] |

[0.78±0.12] |

[0.85±0.02] |

[0.92±0.03] |

[0.89±0.03] |

| A-331440c |

8.53±0.12 |

7.74±0.11 |

9.00±0.14 |

8.27±0.05 |

7.75±0.06 |

8.50±0.04 |

| (ID=14) |

[1.00±0.10] |

[1.14±0.07] |

[1.10±0.23] |

[0.90±0.05] |

[0.81±0.04] |

[0.91±0.03] |

| A-347166d |

9.02±0.09 |

8.69±0.09 |

9.04±0.12 |

8.95±0.7 |

8.60±0.05 |

8.80±0.07 |

| (ID=15) |

[1.09±0.08] |

[1.01±0.02] |

[1.14±0.25] |

[0.80±0.07] |

[0.81±0.03] |

[0.84±0.02] |

| A-349821e |

9.73±0.20 |

9.33±0.10 |

10.5±0.4 |

9.01±0.12 |

8.77±0.05 |

9.46±0.07 |

| (ID=16) | [1.07±0.09] | [1.17±0.07] | [1.13±0.18] | [0.88±0.04] | [0.85±0.03] | [0.93±0.02] |

Binding parameters based on curve fitting to compiled competition curves.

Faghih et al. (2003a) (Compd 8). For chemical structure, see Figure 4a.

Faghih et al. (2002) (Comp 31). For chemical structure, see Figure 4b.

Turner et al. (2003) (Compd 23). For chemical structure, see Figure 4c.

Faghih et al. (2003b) (Compd A6). For chemical structure, see Figure 4d.

Mean pKi (−log inhibition constant) for compounds displaying two-site competition with high-affinity values (upper line) and low-affinity values (lower line), as well as the percentage fraction, F (in parenthesis), are shown. For compounds displaying one-site competition, affinities are expressed as mean pKi±s.e.m., with mean nH±s.e.m. shown on the second line in brackets (N=4–451).

Figure 5.

Displacement curves for [3H]A-349821 in competition with a panel of reference H3 receptor agonists (a–c) and selected H3 receptor ligands with mixed pharmacology (proxyfan and GT-2331) or antagonists/inverse agonists (d–f) in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors (a and d), rat cortical H3 receptors (b and e) or recombinant human H3 receptors (c and f). s.e.m. bars have been omitted for the purpose of clarity. s.e.m. values were typically less than ±10% of the mean. [3H]A-349821 concentrations were ∼1.8, ∼1.6 and ∼0.6 nM for membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors, rat cortical H3 receptors, or recombinant human H3 receptors, respectively. Nonspecific binding was defined by the presence of 10 μM thioperamide. All experiments were carried at 25°C for 60 min with duplicate tubes. Data represent mean±s.e.m. of three or four experiments where each point was determined in duplicate. The curves shown superimposed on the mean data points were described with the best fit (F-test at 95% confidence) by either the ‘one-site competition' or ‘two-site competition' equations using Prism software.

Table 4.

Parameters for multiple data sets from competition experiments using [3H]A-349821 or [3H]NαMH in membranes expressing human or rat H3 receptors

| |

|

[3H]A-349821 |

[3H]NαMH |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Compound |

Chemical |

Rat H3 |

Rat Cortex |

Human H3 |

Rat H3 |

Rat Cortex |

Human H3 |

| |

Series |

pKi |

pKi |

pKi |

pKi |

pKi |

pKi |

| [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | [nH] | ||

|

1aA-347187 |

Tricyclic |

6.81±0.08 |

6.53±0.09 |

6.42±0.14 |

6.57±0.06 |

6.40±0.13 |

6.12±0.07 |

| |

|

[0.83±0.19] |

[1.08±0.03] |

[0.86±0.11] |

[0.75±0.05] |

[0.77±0.05] |

[0.92±0.09] |

|

1bA-349951 |

Tricyclic |

6.93±0.35 |

6.53±0.30 |

7.26±0.30 |

7.10±0.04 |

7.01±0.15 |

7.29±0.10 |

| |

|

[1.03±0.26] |

[0.87±0.06] |

[0.87±0.16] |

[0.81±0.02] |

[0.71±0.10] |

[0.83±0.07] |

|

2A-311346 |

Biaryl |

7.77±0.08 |

6.90±0.19 |

8.09±0.12 |

7.74±0.08 |

7.20±0.33 |

8.06±0.14 |

| |

|

[1.30±0.10] |

[1.03±0.20] |

[0.89±0.10] |

[0.94±0.10] |

[0.78±0.11] |

[0.90±0.07] |

|

3aA-349762 |

Biaryl |

8.71±0.17 |

8.50±0.09 |

9.55±0.17 |

8.48±0.02 |

8.55±0.07 |

9.08±0.12 |

| |

|

[1.10±0.17] |

[1.32±0.10] |

[1.09±0.17] |

[0.97±0.05] |

[0.70±0.02] |

[0.88±0.06] |

|

3bA-349763 |

Biaryl |

8.70±0.06 |

8.43±0.15 |

9.23±0.26 |

8.81±0.09 |

8.42±0.07 |

8.68±0.12 |

| |

|

[0.92±0.17] |

[1.22±0.08] |

[1.45±0.32] |

[0.78±0.07] |

[0.79±0.01] |

[0.97±0.14] |

|

3cA-349765 |

Biaryl |

7.35±0.64 |

7.11±0.72 |

7.87±0.69 |

6.59±0.06 |

6.39±0.10 |

6.96±0.09 |

| |

|

[1.12±0.24] |

[1.23±0.05] |

[1.10±0.19] |

[0.80±0.07] |

[0.62±0.04] |

[0.75±0.05] |

|

3dA-349768 |

Biaryl |

8.71±0.07 |

8.56±0.06 |

9.42±011 |

8.97±0.08 |

8.69±0.07 |

9.10±0.09 |

| |

|

[1.21±0.11] |

[1.09±0.04] |

[1.26±0.19] |

[0.76±0.08] |

[0.79±0.07] |

[0.86±0.05] |

|

3eA-349771 |

Biaryl |

7.45±0.12 |

7.26±0.06 |

8.08±0.11 |

7.52±0.04 |

7.38±0.18 |

8.01±0.14 |

| |

|

[1.13±0.11] |

[1.33±0.14] |

[1.18±0.19] |

[0.80±0.01] |

[0.68±0.06] |

[0.82±0.11] |

|

3fA-349774 |

Biaryl |

7.86±0.01 |

7.55±0.08 |

8.59±0.10 |

7.55±0.05 |

7.67±0.09 |

8.20±0.12 |

| |

|

[1.05±0.15] |

[1.26±0.01] |

[1.14±0.16] |

[0.94±0.07] |

[0.82±0.10] |

[0.95±0.06] |

|

3gA-349777 |

Biaryl |

6.84±0.16 |

6.69±0.04 |

7.29±0.16 |

6.54±0.02 |

6.96±0.09 |

7.61±0.11 |

| |

|

[1.20±0.27] |

[1.17±0.11] |

[1.27±0.14] |

[0.85±0.09] |

[0.68±0.09] |

[0.78±0.09] |

|

3hA-349778 |

Biaryl |

6.39±0.15 |

6.24±0.26 |

6.68±0.13 |

6.32±0.07 |

6.66±0.18 |

6.64±0.11 |

| |

|

[0.90±0.17] |

[1.15±0.07] |

[0.99±0.10] |

[0.82±0.11] |

[0.56±0.20] |

[0.73±0.11] |

|

3iA-349785 |

Biaryl |

6.77±0.08 |

6.23±0.07 |

7.00±0.15 |

6.62±0.11 |

6.33±0.15 |

6.74±0.05 |

| |

|

[1.03±0.19] |

[1.28±0.27] |

[1.08±0.21] |

[1.03±0.07] |

[0.74±0.13] |

[0.86±0.09] |

|

3jA-349786 |

Biaryl |

8.39±0.13 |

7.79±0.20 |

8.98±0.11 |

8.55±0.11 |

8.08±0.13 |

8.46±0.12 |

| |

|

[1.17±0.34] |

[1.23±0.12] |

[1.22±0.24] |

[0.86±0.17] |

[0.79±0.11] |

[0.96±0.06] |

|

3kA-349816 |

Biaryl |

7.29±0.33 |

6.62±0.22 |

7.62±0.29 |

7.26±0.03 |

7.14±0.07 |

7.63±0.17 |

| |

|

[1.05±0.16] |

[1.49±0.19] |

[1.23±0.19] |

[0.93±0.04] |

[0.83±0.02] |

[0.90±0.12] |

|

3lA-349822 |

Biaryl |

7.94±0.16 |

8.03±0.17 |

8.36±0.15 |

8.02±0.05 |

7.97±0.10 |

8.13±0.11 |

| |

|

[1.43±0.22] |

[1.24±0.10] |

[1.32±0.17] |

[0.93±0.02] |

[0.81±0.08] |

[1.00±0.08] |

|

3mA-350810 |

Biaryl |

7.53±0.11 |

7.25±0.09 |

8.36±0.12 |

7.38±0.07 |

6.76±0.26 |

7.39±0.15 |

| [1.16±0.36] | [1.29±0.08] | [1.25±0.31] | [0.78±0.05] | [0.69±0.14] | [0.72±0.05] | ||

1For chemical structures, see Turner et al. (2003) (1a=Compd. 27, 1b=Compd. 28).

For chemical structures, see Faghih et al. (2002) (2=Compd. 29).

For chemical structures, see Faghih et al. (2003b) (3a=Compd. F6, 3b=Compd. F5, 3c=Compd. G1, 3d=Compd. G6, 3e=Compd. D1, 3f=Compd. D3, 3g=Compd. D7, 3h=Compd. E1, 3i=Compd. B1, 3j=Compd. B2, 3k=Compd. B7, 3l=Compd. A5, 3m=Compd. C7).

Mean pKi (−log inhibition constant)±s.e.m., with mean nH±s.e.m. in brackets shown below (N=3–31).

By contrast, competition curves for thioperamide and clobenpropit, both reported to have antagonist/inverse agonist attributes in functional studies (Wieland et al., 2001), were monophasic and best described by one-site curve fits (Table 3 and Figure 5d–f). Similarly, competition curves for four Abbott compounds, representing three distinct chemical series (for chemical structures, see Figure 4), and previously shown to have antagonist/inverse agonist functional properties (Esbenshade et al., 2003; 2004; Turner et al., 2003; Hancock et al., 2004), were monophasic and best described by one-site curve fits (Table 3 and Figure 5d–f). The imidazoles thioperamide and clobenpropit displaced [3H]A-349821 to the same level as the non-imidazole, A-317920 (Figure 5d–f). In addition, a large panel of Abbott compounds from these three chemical series (previously described as H3 receptor antagonists/inverse agonists), which displayed a wide range of potencies in the displacement of [3H]NαMH binding (Faghih et al., 2002, 2003a, 2003b; Turner et al., 2003), were tested in competition with [3H]A-349821. For these compounds as well, competition curves displayed Hill slopes close to or slightly above unity and were best described by the one-site analysis (Table 4).

For comparison, parallel studies were carried out for the complete panel of compounds in competition-binding assays with the H3 receptor agonist radioligand [3H]NαMH (Tables 3 and 4). Competition curves for all compounds displayed Hill slopes close to or slightly below unity and were best described by the one-site curve fit (Tables 3 and 4).

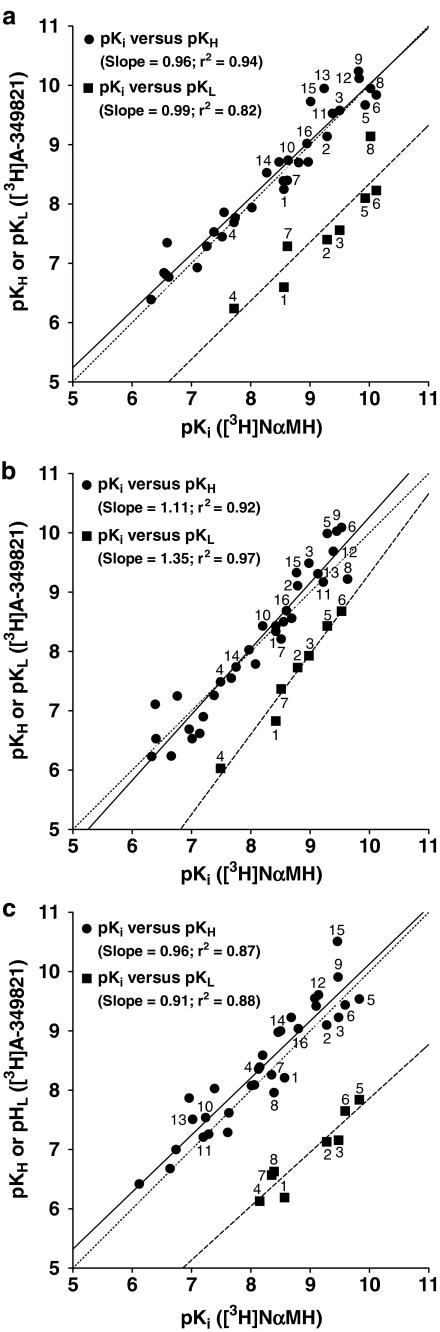

pKi values for antagonists (denoted by pKH) and high- and low-affinity pKi values for agonists (denoted by pKH and pKL, respectively) determined by displacement of [3H]A-349821 binding to membranes from C6 cells expressing rat H3 receptors (Figure 6a), human H3 receptors (Figure 6c), or rat cortices (Figure 6b) were correlated to pKi values for antagonists and agonists obtained by displacement of [3H]NαMH binding. Two distinct regression lines with slopes close to unity were revealed (Figure 6a–c). One regression line was close to the line of unity, as described by pKi values for displacement of [3H]NαMH (pKi) versus high-affinity displacement of [3H]A-349821 from a high-affinity site recognized by both antagonists and agonists (pKH), while another was frame shifted to the right, as described by pKi values for displacement of [3H]NαMH (pKi) versus displacement of [3H]A-349821 from a low-affinity site recognized by agonists (pKL) (Figure 6). In all instances, regression lines were highly correlated (R2⩾0.82).

Figure 6.

Regression lines showing mean affinities for H3 receptor ligands estimated from competition with [3H]NαMH (pKi) or [3H]A-349821 (pKH and pKL) in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors (a), rat cortical H3 receptors (b), and recombinant human H3 receptors (c). The solid line is the linear regression for pKi versus pKH, the dashed line is the linear regression for pKi versus pKL, and the dotted line is the line of identity. Compounds of interest are notated and can be identified by the corresponding compound ID values and compound names included in Table 3. Compounds 1–6 are reference agonists, compounds 7 and 8 (proxyfan and GT-2331, respectively) display mixed pharmacology and compounds 9–16 are antagonists/inverse agonists. Symbols not marked by a number refer to the compounds listed in Table 4.

Saturation studies using [3H]A-349821 and [3H]NαMH: the effect of GDP

The effect of GDP (100 μM) on saturation binding of [3H]A-349821 and [3H]NαMH was investigated, since guanine nucleotides are known to affect agonist affinities for many GPCRs. KD and Bmax values for [3H]A-349821 binding were largely insensitive to GDP in all membranes tested (Table 1 and Figure 7). By contrast, KD values for [3H]NαMH binding to all membranes were significantly reduced by addition of GDP (P<0.05) (Table 1 and Figure 7). Similarly, Bmax values tended to be reduced by addition of GDP, but they were marginally significant only for membranes from rat cortices (P=0.048).

Figure 7.

Representative saturation curves from a total of four experiments for binding of either [3H]A-349821 (open symbols) or [3H]NαMH (solid symbols) to sites in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors (a), cortical rat H3 receptors (b), recombinant human H3 receptors (c), or cortical human H3 receptors (d) in the absence or presence of 100 μM GDP. Panels e–h are Scatchard transformation plots of panels a–d, respectively. All determinations were from duplicate tubes. Saturation studies and data analysis were performed as described in Figure 2, but include simultaneous determinations in the presence of GDP.

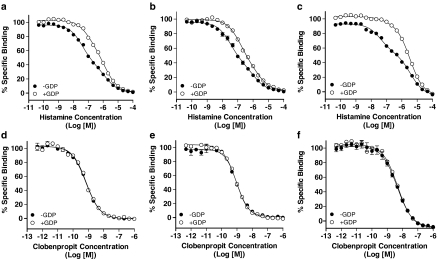

[3H]A-349821 displacement by histamine and clobenpropit: the effect of GDP

Displacement of [3H]A-349821 binding by the endogenous H3 receptor agonist, histamine, displayed shallow slopes that were best fitted by the two-site model, whereas competition curves performed in the presence of GDP were shifted to the right, showing an overall reduction in histamine affinity and an increase in Hill slope values in all membranes tested (Figure 8a–c). However, the displacement curves in the presence of GDP were still best fit by the two-site model. The GDP effect was most pronounced when membranes expressing recombinant human H3 receptors were utilized (Figure 8c). Competition binding with the H3 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist clobenpropit was, in all cases, monophasic and completely insensitive to GDP (Figure 8d–f).

Figure 8.

Representative [3H]A-349821 displacement curves from a total of three experiments for histamine (a–c) or clobenpropit (d–f) in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors (a and d), rat cortical H3 receptors (b and e), and recombinant human H3 receptors (c and f), with (open circles) and without GDP (closed circles). All determinations were from duplicate tubes. Competition studies and data analysis were performed as described in Figure 5, but included addition of either buffer or GDP (100 μM, final concentration) immediately prior to addition of [3H]A-349821.

Discussion

The present study describes the characterization of a novel and highly specific, non-imidazole-containing, H3 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist radioligand, [3H]A-349821, and its use in comparing the pharmacology displayed by membranes expressing recombinant or native H3 receptors from rat or human sources. Specific [3H]A-349821 binding was saturable and displayed high affinity in these membranes. [3H]A-349821 appeared to saturate a single pool of receptors and exhibited very low nonspecific binding, even in membranes from rat cortices (Figure 2), where previously described imidazole-based H3 receptor antagonist radioligands have been reported to significantly label H4 receptors, 5-HT3 receptors or cytochrome P450 sites (Labella et al., 1992; Leurs et al., 1995; Schlicker et al., 1995; Alves-Rodrigues et al., 1996; Harper et al., 1999; Yang et al., 2002). Specific binding of [3H]A-349821 was absent in membranes from the parent cell line and from cell lines expressing α2c adrenoceptors, H4, or 5-HT3 receptors, while specific binding was insensitive to competition by H1 and H2 ligands in membranes expressing H3 receptors (data not shown). Thus, [3H]A-349821 demonstrated high specificity for the H3 receptor, consistent with previous studies in which unlabelled A-349821 used in competition assays showed low affinity (μM) for a large number of GPCRs and ion channels, although weak potency towards α2c adrenoceptors (IC50=250 nM), was observed (Esbenshade et al., 2004). While this potency was similar to the potency of [125I]Iodoproxyfan for α2 adrenoceptors (pKi=162 nM) (Schlicker et al., 1995), disparate interaction of these radioligands with cytochrome P450 sites was found. Previous studies (Yao et al., 2005) showed that [125I]iodoproxyfan binding was displaced differentially by thioperamide, which competed for a low-affinity binding site that was sensitive to the cytochrome P450 inhibitor metyrapone, whereas the non-imidazole A-317920 did not interact with this site. In the current study, [3H]A-349821 binding was displaced equally by both thioperamide and A-317920 (Figure 5d–f) and saturation analysis with [3H]A-349821 (0.06–6 nM) showed identical inhibition of binding by thioperamide and A-317921 (data not shown), suggesting that, unlike [125I]Iodoproxyfan, [3H]A-349821 does not label cytochrome P450 sites.

While [3H]A-349821 bound to an apparent single class of receptors, [3H]NαMH saturation binding suggested interaction with both high- and low-affinity sites, although accurate estimation of the low-affinity binding parameters was not possible and, as such, saturation data are reported for single-site occupancy. By contrast, while [3H]NαMH showed decreased specific binding, binding affinity (pKD), and Bmax values upon exposure to GDP, which converts GPCRs from the high- to low-affinity state for agonists, binding of [3H]A-349821 was largely insensitive to GDP (Table 1 and Figure 7), consistent with its previously reported antagonist/inverse agonist properties. Interestingly, the binding of [125I]Iodoproxyfan, a compound originally described as an antagonist radioligand, like that of [3H]NαMH, has been reported to be sensitive to guanylnucleotides (Ligneau et al., 1994). This observation is consistent with several publications describing agonist properties associated with iodoproxyfan (Schlicker et al., 1995; 1996; Wulff et al., 2002).

Saturation-binding studies utilizing membranes prepared from cortical tissue or from C6 cells stably expressing either rat or human H3 receptors further revealed that [3H]A-349821 labelled a larger population of receptors compared to [3H]NαMH (Figure 2). This may be accounted for by [3H]A-349821 stabilizing the inactive H3 receptor conformation, to which it binds with high affinity, or by [3H]A-349821 binding with equivalent affinity to either the inactive or active state of the receptor. Conversely, [3H]NαMH binds with high affinity only to the active state of the receptor, while the receptors in the inactive state would remain largely undetected over the concentrations of [3H]NαMH that are useable in saturation studies. Consistent with the observation that [3H]NαMH detected roughly 50% of the receptor population identified by [3H]A-349821 in the saturation-binding studies (Table 1), the population of high-affinity sites detected with agonists in competition with [3H]A-349821 was found to be roughly 50% (Table 3). Of note is that Bmax values reported for [125I]iodoproxyfan binding in rat cortical membranes were similar to those reported for [3H]NαMH or [3H]RαMH binding (Arrang et al., 1987; West et al., 1990a, 1990b; Ligneau et al., 1994), suggesting that [125I]iodoproxyfan, like other agonist radioligands, detected only a fraction of the total H3 receptors. Thus, [3H]A-349821 may provide a more accurate assessment of H3 receptor density, which may be helpful for membrane-binding and autoradiographic studies, particularly in native tissue. Although [3H]A-349821 is a useful radiolabel for detection of H3 receptors, modest specific activity, in combination with very high affinity, requires careful modifications of assay conditions to avoid ligand depletion, a limitation that may be overcome by improving the current radiolabelling process to increase specific activity.

In kinetic studies, [3H]A-349821 bound rapidly to a single site, with equilibrium achieved in all membranes within 5–15 min (Figure 3). Dissociation constants derived from kinetic studies agreed with values obtained in saturation studies and showed that [3H]A-349821 bound with approximately 10-fold higher affinity towards human compared to rat H3 receptors due to a combination of faster on-rates and slower off-rates (Table 2).

Studies using a large panel of H3 receptor ligands in competition with [3H]A-349821 gave potencies highly correlated with those observed for [3H]NαMH (R2⩾0.82), consistent with labelling of the H3 receptor by [3H]A-349821 (Figure 6). Competition for [3H]A-349821 binding by H3 receptor ligands was biphasic for compounds previously shown to be agonists, but monophasic for antagonists/inverse agonists (Tables 3 and 4 and Figure 5). GDP induced rightward shifts and increased Hill slopes for displacement curves with the H3 receptor agonist histamine, but had no effect on displacement by the H3 receptor antagonist clobenpropit (Figure 8). By contrast, competition against [3H]NαMH was monophasic for all ligands, presumably owing to the labelling of predominantly high-affinity sites at the concentrations of [3H]NαMH used for competition studies (∼0.5 nM). The findings that (1) [3H]A-349821 labelled predominantly one site while [3H]NαMH labelled two sites; (2) specific binding, Bmax and pKD values determined for [3H]NαMH but not [3H]A-349821 were affected by GDP; and (3) histamine displacement of [3H]A-349821 was shifted to the right by GDP, are consistent with G-protein modulation of interconvertable high- and low-affinity states for H3 receptors.

Inspection of high- and low-affinity binding parameters estimated from displacement of [3H]A-349821 by reference H3 receptor agonists revealed a subtle species difference (Table 3). Mean fractions of high-affinity sites for agonists were higher at recombinant or cortical rat H3 receptors compared to recombinant human H3 receptors (52±15, 47±11, and 37±7%, respectively, P<0.05). Another interesting observation is that the differences between mean potencies for high- and low-affinity states (pKH−pKL=ΔpKi; derived from Table 3) for agonists were smaller in membranes expressing recombinant or cortical rat H3 receptors compared to membranes expressing recombinant human H3 receptors (1.67±0.19, 1.48±0.08, and 1.97±0.20, respectively; P<0.05). This trend is reflected in the correlation plots that show a greater frame shift with respect to high- and low-affinity sites for the human H3 receptor compared to rat (Figure 6). Taken together, these results provide a body of evidence supporting the idea that discrimination of agonist binding to high- and low-affinity sites is less pronounced in rat versus human H3 receptors.

Pharmacological comparisons utilizing [3H]A-349821 further revealed that although expression levels of H3 receptors were 10-fold higher in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors compared to those expressing cortical rat H3 receptors (2190 and 227 fmol mg protein−1, respectively), the mean proportion of high-affinity sites recognized by all agonists tested remained unchanged (49±9 and 51±11%, respectively), as did the differences between mean pKH and pKL values (1.67±0.19 and 1.48±0.08, respectively) (Tables 1 and 3). Furthermore, histamine competition curves against [3H]A-349821 showed a similar degree of sensitivity to GDP in membranes expressing recombinant rat H3 receptors compared to those from rat cortices (Figure 8). Taken together, these results suggest that the proportion of high-affinity sites, as well as the ability of agonists to differentiate between high- and low-affinity sites, is largely independent of expression level and the milieu in which the rat H3 receptor is expressed. Since multiple rat H3 receptor isoforms are present in the cortex (Drutel et al., 2001), these data further indicate that, under these conditions, multiple H3 receptor isoforms do not affect the apparent proportions of affinity states, either because of lower expression levels and/or similar binding properties.

It is notable that full agonists showed a clear discrimination between recognition of high- and low-affinity binding sites, while ligands having only antagonist and/or inverse agonist properties did not. Proxyfan and GT-2331, two compounds that have been previously shown to be functionally similar across a range of assays, displayed differential pharmacological classification ranging from antagonism to full agonism, depending on G-protein subtypes and the system in which the functional measurements were made (Krueger et al., 2005). Of interest, proxyfan has been previously described as a ‘protean agonist', being able to act as an agonist in systems where the constitutive activity is low or as an inverse agonist in systems where the constitutive activity is high (Gbahou et al., 2003). Consistent with this differential pharmacological behavior, competition-binding studies utilizing proxyfan and GT-2331 showed varied ability to discriminate between high- and low-affinity binding sites, different from the results seen with full agonists or antagonist/inverse agonists. While several pharmacological properties are similar for proxyfan and GT-2331, it should be mentioned that significant differences between these two compounds are apparent as GT-2331 binds with higher affinity to rat compared to human H3 receptors, while the affinity of proxyfan is roughly the same (Table 3).

In conclusion, the novel non-imidazole-containing antagonist/inverse agonist radioligand, [3H]A-349821, labelled both rat and human H3 receptors with high affinity and selectivity. The results described herein show that [3H]A-349821 labels interconvertable high- and low-affinity H3 receptor sites, revealing the aspects of H3 receptor affinity states with improved definition. Competition data using this radioligand indicate subtle species differences with respect to the pharmacology of receptor states by suggesting that rat H3 receptor activation may be more facile compared to that of human. Investigation of high- and low-affinity H3 receptor states using [3H]A-349821 in competition assays also allowed for the delineation of compounds displaying differential pharmacology from those displaying only full agonism, suggesting a relationship between binding properties and intrinsic activity. Application to membranes expressing recombinant and native H3 receptors from various species could provide further comparative insights into H3 receptor pharmacology.

Acknowledgments

This paper is dedicated to the memory of Arthur A. Hancock, a renowned expert in the field of histamine receptor research, our mentor and friend. He will be missed by all who had the pleasure of knowing him.

Abbreviations

- GPCR

G-protein-coupled receptor

- HEK-293

human embryonic kidney cells

- kob

observed rate constant

- koff

dissociation rate constant

- kon

association rate constant

- NαMH

(N)-α-methylhistamine

- RαMH

(R)-α-methyl-histamine

- SαMH

(S)-α-methylhistamine

References

- ALVES-RODRIGUES A., LEURS R., WU T., PRELL G., FOGED C., TIMMERMAN H. [3H]-thioperamide as a radioligand for the histamine H3 receptor in rat cerebral cortex. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1996;118:2045–2052. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15642.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARRANG J., GARBARG M., LANCELOT J., LECOMTE J., POLLARD H., ROBBA M., SCHUNACK W., SCHWARTZ J. Highly potent and selective ligands for histamine H3-receptors. Nature. 1987;327:117–123. doi: 10.1038/327117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ARRANG J., ROY J., MORGAT J., SCHUNACK W., SCHWARTZ J. Histamine H3 receptor binding sites in rat brain membranes: modulations by guanine nucleotides and divalent cations. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1990;188:219–227. doi: 10.1016/0922-4106(90)90005-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN J.D., O'SHAUGHNESSY C.T., KILPATRICK G.J., SCOPES D.I., BESWICK P., CLITHEROW J.W., BARNES J.C. Characterisation of the specific binding of the histamine H3 receptor antagonist radioligand 3HGR168320. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1996;311:305–310. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(96)00428-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHENG Y.C., PRUSOFF W. Relationship between the inhibition constant Ki and the concentration of inhibitor which causes 50% inhibition (IC50) of an enzymatic reaction. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1973;22:2099–2108. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(73)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CHILDERS S.R., LARIVIERE G. Modification of guanine nucleotide-regulatory components in brain membranes. II. Relationship of guanosine 5′-triphosphate effects on opiate receptor binding and coupling receptors with adenylate cyclase. J. Neurosci. 1984;4:2764–2771. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.04-11-02764.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK M.A., KORTE A., EGAN R.W. Guanine nucleotides and pertussis toxin reduce the affinity of histamine H3 receptors on AtT-20 cells. Agents Actions. 1993;40:129–134. doi: 10.1007/BF01984051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DRUTEL G., PEITSARO N., KARLSTEDT K., WIELAND K., SMIT M., TIMMERMAN H., PANULA P., LEURS R. Identification of rat H3 receptor isoforms with different brain expression and signaling properties. Mol. Pharmacol. 2001;59:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESBENSHADE T.A., FOX G.B., KRUEGER K.M., BARANOWSKI J.L., MILLER T.R., KANG C.H., DENNY L.I., WITTE D.G., YAO B.B., PAN J.B., FAGHIH R., BENNANI Y.L., WILLIAMS M., HANCOCK A.A. Pharmacological and behavioral properties of A-349821, a selective and potent human histamine H3 receptor antagonist. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2004;68:933–945. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2004.05.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESBENSHADE T.A., FOX G.B., KRUEGER K.M., MILLER T.R., KANG C.H., DENNY L.I., WITTE D.G., YAO B.B., PAN L., WETTER J., MARSH K., BENNANI Y.L., COWART M.D., SULLIVAN J.P., HANCOCK A.A. Pharmacological properties of ABT-239 [4-(2-{2-[(2R)-2-methylpyrrolidinyl] ethyl}-benzofuran-5-yl)benzonitrile]: I. Potent and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist with drug-like properties. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2005a;313:165–175. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.078303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESBENSHADE T.A., HANCOCK A.A.Characterization of histaminergic receptors Curr. Prot. Pharmacol. 200011.19.1–1.19.19 [Google Scholar]

- ESBENSHADE T.A., KRUEGER K.M., MILLER T.R., KANG C.H., DENNY L.I., WITTE D.G., YAO B.B., FOX G.B., FAGHIH R., BENNANI Y.L., WILLIAMS M., HANCOCK A.A. Two novel and selective nonimidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonists A-304121 and A-317920: I. In vitro pharmacological effects. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2003;305:887–896. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.047183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ESBENSHADE T.A., YAO B.B., WITTE D.G., CARR T.L., BARANOWSKI J.L., KRUEGER K.M., MILLER T.R., SURBER B.W., FAGHIH R., HANCOCK A.A. Use of novel, non-imidazole inverse agonist radioligands to define H3 receptor pharmacology. Inflamm. Res. 2005b;54:S46–S47. doi: 10.1007/s00011-004-0421-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGHIH R., DWIGHT W., PAN J.B., FOX G.B., KRUEGER K.M., ESBENSHADE T., MCVEY J.M., MARSH K., BENNANI Y.L., HANCOCK A.A. Synthesis and SAR of aminoalkoxy-biaryl-4-carboxamides: novel and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonists. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003a;13:1325–1328. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00118-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGHIH R., DWIGHT W., VASUDEVAN A., DINGES J., CONNER-SCOTT E., ESBENSHADE TIMOTHY A., BENNANI YOUSSEF L., HANCOCK ARTHUR A. Aminoalkoxybiphenylnitriles as histamine-3 receptor ligands. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2002;12:3077–3079. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00648-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FAGHIH R., PHELAN K., ESBENSHADE T.A., MILLER T.R., KANG C.H., KRUEGER K.M., YAO B.B., FOX G.B., BENNANI Y.L., HANCOCK A.A. -alanine piperazine-amides: novel non-imidazole antagonists of the histamine H3 receptor. Inflamm. Res. 2003b;52:S47–S88. doi: 10.1007/s000110300049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GBAHOU F., ROULEAU A., MORISSET S., PARMENTIER R., CROCHET S., LIN J., SHENG L.J., LIGNEAU X., TARDIVEL L., JOËL T.L., STARK H., SCHUNACK W., GANELLIN C.R., SCHWARTZ J.C., ARRANG J.M. Protean agonism at histamine H3 receptors in vitro and in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2003;100:11086–11091. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932276100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HAMBLIN M.W., CREESE I. 3H-dopamine binding to rat striatal D-2 and D-3 sites: enhancement by magnesium and inhibition by guanine nucleotides and sodium. Life Sci. 1982;30:1587–1595. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(82)90248-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HANCOCK A.A., BENNANI Y.L., BUSH E.N., ESBENSHADE T.A., FAGHIH R., FOX G.B., JACOBSON P., KNOUREK S.V., KRUEGER K.M., NUSS M.E., PAN J.B., SHAPIRO R., WITTE D.G., YAO B.B. Antiobesity effects of A-331440, a novel non-imidazole histamine H3 receptor antagonist. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2004;487:183–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARPER E.A., SHANKLEY N.P., BLACK J.W. Characterization of the binding of of [3H]-clobenpropit to histamine H3-receptors in guinea pig cerebral cortex membranes. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1999;128:881–890. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JANSEN F.P., RADEMAKER B., BAST A., TIMMERMAN H. The first radiolabeled histamine H3 receptor antagonist, [125I]iodophenpropit: saturable and reversible binding to rat cortex membranes. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1992;217:203–205. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90851-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KILPATRICK G., MICHEL A. Characterisation of the binding of the histamine H3 receptor agonist [3H] (R)-alpha methyl histamine to homogenates of rat and guinea-pig cortex. Agents Actions Suppl. 1991;33:69–75. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-7309-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KIM M.H., NEUBIG R.R. Membrane reconstitution of high-affinity alpha 2 adrenergic agonist binding with guanine nucleotide regulatory proteins. Biochemistry. 1987;26:3664–3672. doi: 10.1021/bi00386a061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KITBUNNADAJ R., HASHIMOTO T., POLI E., ZUIDERVELD O.P., MENOZZI A., HIDAKA R., DE E., IWAN J.P., BAKKER R.A., MENGE W.M.P.B., YAMATODANI A., CORUZZI G., TIMMERMAN H., LEURS R. N-substituted piperidinyl alkyl imidazoles: discovery of methimepip as a potent and selective histamine H3 receptor agonist. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:2100–2107. doi: 10.1021/jm049475h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KRUEGER K.M., WITTE D.G., IRELAND-DENNY L.M., MILLER T.R, BARANOWSKI J.L., BUCKNER S., MILICIC I., ESBENSHADE T.A., HANCOCK A.A. G protein-dependent pharmacology of histamine H3 receptor ligands: evidence for heterogeneous active state receptor conformations. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2005. pp. 271–281. [DOI] [PubMed]

- LABELLA F., QUEEN G., GLAVIN G., DURANT G., STEIN D., BRANDES L. H3 receptor antagonist, thioperamide, inhibits adrenal steroidogenisis and histamine binding to adrenocortical microsomes and binds to cytochrome P450. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;107:161–164. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEFF P., DOUGALL I. Further concerns over Cheng–Prusoff analysis. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1993;14:110–112. doi: 10.1016/0165-6147(93)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEURS R., TULP M.T., MENGE W.M., ADOLFS M.J., ZUIDERVELD O.P., TIMMERMAN H. Evaluation of the receptor selectivity of the H3 receptor antagonists, iodophenpropit and thioperamide: an interaction with the 5-HT3 receptor revealed. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1995;116:2315–2321. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb15071.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIGNEAU X., GARBARG M., VIZUETE M.L., DIAZ J., PURAND K., STARK H., SCHUNACK W., SCHWARTZ J.C. [125I]iodoproxyfan, a new antagonist to label and visualize cerebral histamine H3 receptors. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 1994;271:452–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIU H., KERDESKY F.A., BLACK L.A., FITZGERALD M., HENRY R., ESBENSHADE T.A., HANCOCK A.A., BENNANI Y.L. An efficient multigram synthesis of the potent histamine H(3) antagonist GT-2331 and the reassessment of the absolute configuration. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:192–194. doi: 10.1021/jo035264t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MORISSET S., ROULEAU A., LIGNEAU X., GBAHOU F., TARDIVEL-LACOMBE J., STARK H., SCHUNACK W., GANELLIN C.R., SCHWARTZ J.C., ARRANG J.M. High constitutive activity of native H3 receptors regulates histamine neurons in brain. Nature. 2000;408:860–864. doi: 10.1038/35048583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PARKINSON F.E., FREDHOLM B.B. Magnesium-dependent enhancement of endogenous agonist binding to A1 adenosine receptors: a complicating factor in quantitative autoradiography. J. Neurochem. 1992;58:941–950. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1992.tb09347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHLICKER E., PERTZ H., BITSCHNAU H., PURAND K., KATHMANN M., ELZ S., SCHUNACK W. Effects of iodoproxyfan, a potent and selective histamine H3 receptor antagonist, on alpha 2 and 5-HT3 receptors. Inflamm. Res. 1995;44:296–300. doi: 10.1007/BF02032572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHLICKER E., KATHMANN M., BITSCHNAU H., MARR I., REIDEMEISTER S., STARK H., SCHUNACK W. Potencies of antagonists chemically related to iodoproxyfan at histamine H3 receptors in mouse brain cortex and guinea-pig ileum: evidence for H3 receptor heterogeneity. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg's Arch. Pharmacol. 1996;353:482–488. doi: 10.1007/BF00169166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SMITH P.K., KROHN R.I., HERMANSON G.T., MALLIA A.K., GARTNER F.H., PROVENZANO M.D., FUJIMOTO E.K., GOEKE N.M., OLSON B.J., KLENK D.C. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal. Biochem. 1985;150:76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- TURNER S.C., ESBENSHADE T.A., BENNANI Y.L., HANCOCK A.A. A new class of histamine H3-receptor antagonists: synthesis and structure–activity relationships of 7,8,9,10-tetrahydro-6H-cyclohepta (b)quinolines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2003;13:2131–2135. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(03)00356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- VAN DER GOOT H., TIMMERMAN H. Selective ligands as tools to study histamine receptors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2000;35:5–20. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)00101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST R.E., JR, ZWEIG A., SHIH N.Y., SIEGEL M.I., EGAN R.W., CLARK M.A. Identification of two H3-histamine receptor subtypes. Mol. Pharmacol. 1990a;38:610–613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WEST R.E.J., ZWEIG A., GRANZOW R.T., SIEGEL M.I., EGAN R.W. Biexponential kinetics of (R)-alpha-[3H]methylhistamine binding to the rat brain H3 histamine receptor. J. Neurochem. 1990b;55:1612–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1990.tb04946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WIELAND K., BONGERS G., YAMAMOTO Y., HASHIMOTO T., YAMATODANI A., MENGE W.M.B.P., TIMMERMAN H., LOVENBERG T.W., LEURS R. Constitutive activity of histamine H-3 receptors stably expressed in SK-N-MC cells: display of agonism and inverse agonism by H-3 antagonists. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Therap. 2001;299:908–914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WULFF B.S., HASTRUP S., RIMVALL K. Characteristics of recombinantly expressed rat and human histamine H3 receptors. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2002;453:33–41. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANAI K., RYU J.H., SAKAI N., TAKAHASHI T., IWATA R., IDO T., MURAKAMI K., WATANABE T. Binding characteristics of a histamine H3-receptor antagonist, [3H]S-methylthioperamide: comparison with [3H](R)alpha-methylhistamine binding to rat tissues. Japan. J. Pharmacol. 1994;65:107–112. doi: 10.1254/jjp.65.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YANG R., HEY J.A., ASLANIAN R., RIZZO C.A. Coordination of histamine H3 receptor antagonists with human adrenal cytochrome P450 enzymes. Pharmacology. 2002;66:128–135. doi: 10.1159/000063794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO B.B., HUTCHINS C.W., CARR T.L., CASSAR S., MASTERS J.N., BENNANI Y.L., ESBENSHADE T.A., HANCOCK A.A. Molecular modeling and pharmacological analysis of species-related histamine H-3 receptor heterogeneity. Neuropharmacology. 2003;44:773–786. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(03)00056-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- YAO B.B., WITTE D.G., MILLER T.R., CARR T.L., KANG C.H., CASSAR S., FAGHIH R., BENNANI Y.L., SURBER B.W., HANCOCK A.A., ESBENSHADE T.A. Use of an inverse agonist radioligand [3H]A-317920 reveals distinct pharmacological profiles of the rat histamine H3 receptor. Neuropharmacology. 2005;44:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]