Abstract

Atomic force microscopes and optical tweezers are widely used to probe the mechanical properties of individual molecules and molecular interactions, by exerting mechanical forces that induce transitions such as unfolding or dissociation. These transitions often occur under nonequilibrium conditions and are associated with hysteresis effects—features usually taken to preclude the extraction of equilibrium information from the experimental data. But fluctuation theorems1–5 allow us to relate the work along nonequilibrium trajectories to thermodynamic free-energy differences. They have been shown to be applicable to single-molecule force measurements6 and have already provided information on the folding free energy of a RNA hairpin7,8. Here we show that the Crooks fluctuation theorem9 can be used to determine folding free energies for folding and unfolding processes occurring in weak as well as strong nonequilibrium regimes, thereby providing a test of its validity under such conditions. We use optical tweezers10 to measure repeatedly the mechanical work associated with the unfolding and refolding of a small RNA hairpin11 and an RNA three-helix junction12. The resultant work distributions are then analysed according to the theorem and allow us to determine the difference in folding free energy between an RNA molecule and a mutant differing only by one base pair, and the thermodynamic stabilizing effect of magnesium ions on the RNA structure.

The Crooks fluctuation theorem9 (CFT) predicts a symmetry relation in the work fluctuations associated with the forward and reverse changes a system undergoes as it is driven away from thermal equilibrium by the action of an external perturbation. This theorem applies to processes that are microscopically reversible, and its experimental evaluation in small systems is crucial to understand better the foundations of nonequilibrium physics13. A consequence of the CFT is Jarzynski’s equality14, which relates the equilibrium free-energy difference ΔG between two equilibrium states to an exponential average (denoted by angle brackets) of the work done on the system, W, taken over an infinite number of repeated none-quilibrium experiments, exp(−ΔG/kBT) = 〈exp(−W/kBT)〉. The equality has been developed6 into a formalism that allows us to use nonequilibrium single-molecule pulling experiments to reconstruct free-energy profiles or potentials of mean force15 along reaction coordinates. Experimental testing of Jarzynski’s equality in single-molecule force experiments16 used the P5ab RNA hairpin7,8, which can be folded and unfolded quasi-reversibly. But for processes that occur far from equilibrium, the applicability of Jarzynski’s equality is hampered by large statistical uncertainties that arise from the sensitivity of the exponential average to rare events17,18 (low values of W). Moreover, although the equality 〈W〉 = ΔG holds for processes occurring near equilibrium, spatial drift in the experimental system usually makes it difficult in practice to extract unfolding free energies using small loading rates (below a few pN s−1). Drift effects decrease noticeably for larger pulling speeds, making it possible to obtain more reliable experimental data (and also good statistics as a large number of pulls can be executed in a reasonable time), but at the expense of a more irreversible unfolding process. Here we show that significant improvements can be obtained by using the CFT, which provides a more robust and more rapidly converging method to extract equilibrium free energies from non-equilibrium processes.

The CFTallows us to quantify the amount of hysteresis observed in the values of the irreversible work done to unfold and refold a macromolecule. Let PU(W) denote the probability distribution of the values of the work performed on the molecule in an infinite number of pulling experiments along the unfolding (U) process, and define PR(W) analogously for the reverse (R) process. For the CFT to be applicable, the unfolding and refolding processes need to be related by time-reversal symmetry, that is, in our experiments, the optical trap used to manipulate the molecule must be moved at the same speeds during unfolding and refolding. Moreover, the molecular transition probed always has to start in an equilibrium state (folded in the unfolding process, and denatured or unfolded in the refolding process) and reach a well-defined final state. The CFT9 then predicts that:

| (1) |

where ΔG is the free-energy change between the final and the initial states, and thus equal to the reversible work associated with this process. Note that the CFT does not require that the system studied reaches its final equilibrium state immediately after the unfolding and refolding processes have been completed; it is only the control parameter that needs to attain its final value, whereas the system may continue to equilibrate to a well-defined state that is consistent with the final value of the control parameter. The equilibration occurs without change of the control parameter, and therefore contributes no work. In principle, W is an integral over the external variation of a control parameter9, for example, the position of the optical trap or the time6. In our experiments, W is well approximated by the familiar force-versus-extension integral:

| (2) |

where xi is the distance between the ends of the molecule and Ns is the number of intervals used in the sum (see ref. 6 for a thorough discussion of this issue). Relation (1) quantifies hysteretic effects in the pulling experiment: work values larger than ΔG occur most often along the unfolding path while (absolute) values smaller than ΔG occur more often along the refolding path. As can be seen from equation (1), the CFT states that although P U(W), P R(−W) depend on the pulling protocol, their ratio depends only on the value of ΔG. Thus the value of ΔG can be determined once the two distributions are known. In particular, the two distributions cross at W = ΔG:

| (3) |

regardless of the pulling speed. Although the simple identity (3) already gives an estimate of ΔG, it is not necessarily very precise because it uses only the local behaviour of the distribution around W = ΔG. Using the whole work distribution increases the precision of the free-energy estimate19. In particular, as we show below, when the overlapping region of work values between the unfolding and refolding work distributions is too narrow (as may happen for large values of the average dissipated work, defined as 〈W dis〉 = 〈W〉 − ΔG), the use of Bennett’s acceptance ratio method20 makes it possible to extract accurate estimates of ΔG using the CFT (see the Supplementary Information).

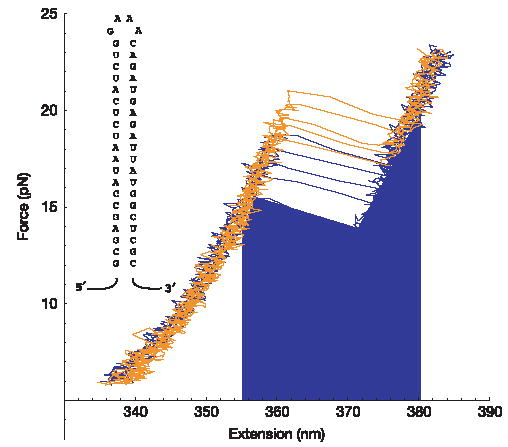

We first experimentally test the validity of the CFT for a molecular transition occurring near equilibrium. For this, we use a short interfering (si)RNA hairpin that targets the messenger RNA of the CD4 receptor of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)11 and that unfolds irreversibly but not too far from equilibrium at accessible experimental pulling speeds (dissipated work values less than 6k BT). Under these conditions, the unfolding and refolding work distributions overlap over a sufficiently large range of work values to justify the use of the direct method to experimentally test equation (1). The work done on the molecules during either pulling or relaxation is given by the areas below the corresponding force–extension curves (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Force–extension curves.

The stochasticity of the unfolding and refolding process is characterized by a distribution of unfolding or refolding work trajectories. Five unfolding (orange) and refolding (blue) force–extension curves for the RNA hairpin are shown (loading rate of 7.5 pN s−1). The blue area under the curve represents the work returned to the machine as the molecule switches from the unfolded to the folded state. The RNA sequence is shown as an inset.

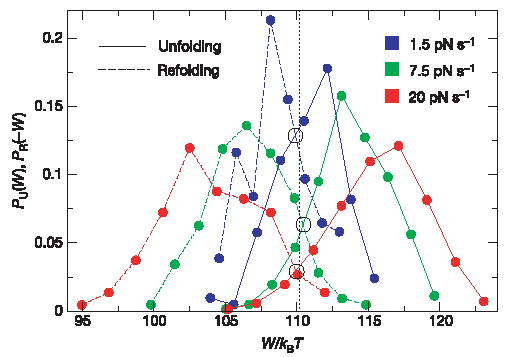

Unfolding and refolding work distributions at three different pulling speeds are shown in Fig. 2. Irreversibility increases with the pulling speed and unfolding–refolding work distributions become progressively more separated. Note, however, that the unfolding and the refolding distributions cross at a value of the work ΔG = 110.3 ±0.5 kBT that does not depend on the pulling speed, as predicted by equation (3). Moreover, the work distributions also satisfy the CFT, that is, equation (1) (see the Supplementary Information). We also notice that work distributions are compatible with, and can be fitted to, gaussian distributions (data not shown). After subtracting the contribution arising from the entropy loss due to the stretching of the molecular handles attached on both sides of the hairpin (ΔGhandles = 23.8 k BT) and of the extended single-stranded (ss)RNA (ΔGssRNA = 23.7 ±1kBT) from the total work, ΔGexp = 110.3 ±0.5 kBT, we obtain for the free energy of unfolding at zero force = 62.8 ±1.5kBT = 37.2 ±1 kcalmol−1 (at 25° C, in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 1 mM EDTA), in excellent agreement with the result obtained using the Visual OMP from DNA software21 = 38 kcal mol−1 (at 25° C, in 100 mM NaCl).

Figure 2. Test of the CFT using an RNA hairpin.

Work distributions for RNA unfolding (continuous lines) and refolding (dashed lines). We plot negative work, PR(−W), for refolding. Statistics: 130 pulls and three molecules (r = 1.5pNs−1), 380 pulls and four molecules (r = 7.5pNs−1), 700 pulls and three molecules (r = 20.0pNs−1), for a total of ten separate experiments. Good reproducibility was obtained among molecules (see Supplementary Fig. S2). Work values were binned into about ten equally spaced intervals. Unfolding and refolding distributions at different speeds show a common crossing around ΔG = 110.3kBT.

To extend the experimental test of the validity of the CFT to the very-far-from-equilibrium regime where the work distributions are no longer gaussian, we apply the CFT to determine: (1) the difference in folding free energy between an RNA molecule and a mutant that differs only by one base-pair, and (2) the thermodynamic stabilizing effect of Mg2+ ions on the RNA structure. The RNA we consider is a three-helix junction of the 16S ribosomal RNA of Escherichia coli12 that binds the S15 protein. The secondary structure of this RNA is a common feature in RNA structures22–24 that plays, in this case, a crucial role in the folding of the central domain of the 30S ribosomal subunit. For comparison, and to verify the accuracy of the method, we have pulled the wild type and a C·G to G·C mutant (C754G to G587C) of the three-helix junction.

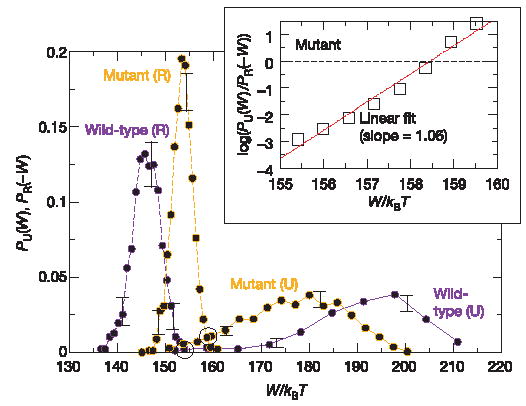

Figure 3 depicts the unfolding and refolding work distributions for the wild-type and mutant molecules (work values were binned into about 10–20 equally spaced intervals). For both molecules, the distributions display a very narrow overlapping region. In contrast with the hairpin distribution, the average dissipated work for the unfolding pathway is now much larger—in the range 20–40kBT —and the unfolding work distribution shows a large tail and strong deviations from gaussian behaviour. Thus, these molecules are ideal to test the validity of equation (1) in the far-from-equilibrium regime. As shown in the inset of Fig. 3, the plot of the log ratio of the unfolding to the refolding probabilities versus total work done on the molecule can be fitted to a straight line with a slope of 1.06, thus establishing the validity of the CFT (see equation (1)) under far-from-equilibrium conditions. Our measurements reveal the presence of long tails in the work distribution P U(W) along the unfolding path and narrow work distributions PR(W) along the refolding path. These distributions complement each other, one being large where the other is small, thereby providing thermodynamically important information about the free-energy landscape.

Figure 3. Free-energy recovery and test of the CFT for non-gaussian work distributions.

Experiments were carried out on the wild-type and mutant S15 three-helix junction without Mg2+. Unfolding (continuous lines) and refolding (dashed lines) work distributions. Statistics: 900 pulls and two molecules (wild type, purple); 1,200 pulls and five molecules (mutant type, orange). Crossings between distributions are indicated by black circles. Work histograms were found to be reproducible among different molecules (error bars indicating the range of variability). Inset, test of the CFT for the mutant. Data have been linearly interpolated between contiguous bins of the unfolding and refolding work distributions.

Bennett’s acceptance ratio method gives ΔGexp = 154.1 ±0.4kBT and ΔGexp = 157.9 ±0.2 kBT for unfolding the wild-type and mutant types, respectively, giving a difference between the two forms = ΔΔGexp = 3.8 ±0.6kBT. After subtracting the (identical for both molecules) handle and RNA entropy loss contributions (97 ±1 kBT) we get = 57 ±1.5kBT (wild type) and = 60.8 ±1.5 kBT (mutant), the error increasing owing to the uncertainty in the contributions coming from the stretching of ssRNA. Free-energy prediction programs such as Mfold25 and Visual OMP21 give a = 2 ±2 kBT between the forms (at 25 °C and 100 mM NaCl). Thus, when combined with acceptance ratio methods, the CFT furnishes a method precise enough to determine the difference in the folding free energies of RNA molecules differing only by one base pair in 34 base pairs.

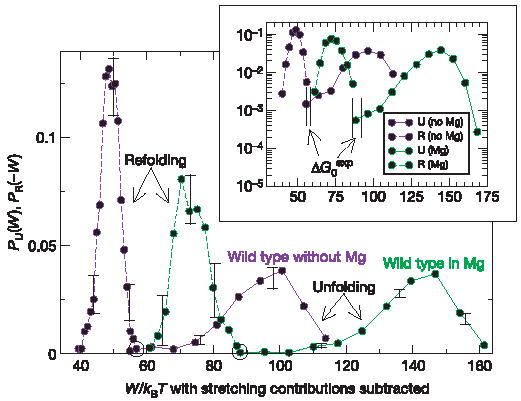

Finally we apply equation (1) to obtain the free energy of stabilization by Mg2+ of the S15 three-helix junction. These values are often difficult to access using bulk methods because melting temperatures of tertiary folded RNAs are frequently higher than the boiling point of water, and Mg2+ catalyses the hydrolysis of RNA at increased temperatures26. Figure 4 depicts the work histograms in the presence and absence of Mg2+ (at constant ionic strength); stretching contributions differ in the presence and absence of magnesium ions (116.8 kBT and 97 k BT, respectively). These values have been subtracted from the work data to properly compare the unfolding free energies of both molecules. The strong increase of irreversibility due to Mg2+ can be seen in the large value of the average dissipated work (about 50 k BT along the unfolding reaction and 16 k BT along the refolding path). Applying Bennett’s acceptance ratio method for the molecule in the presence of magnesium yields ΔGexp = 205.5 ± 1.5kBT and (after subtracting the stretching contributions) gives = 88.7 ±2.5 kBT for the unfolding reaction of the wild-type junction in 4 mM MgCl2. The difference in free energies of unfolding in the presence and absence of Mg2+, = −31.7 ±2 kBT, gives the free energy of stabilization associated with the binding of Mg2+ ions to the S15 three-helix junction through both specific and non-specific (shielding) interactions.

Figure 4. Use of CFT to extract the stabilizing contribution of Mg2+ to the free energy of the S15 three-helix junction (wild type).

Unfolding (continuous lines) and refolding (dashed lines) work distributions. Green curves, 450 pulls and two molecules in Mg2+; purple curves, 900 pulls and two molecules without Mg2+. Crossings between distributions are indicated by black circles. Work histograms are reproducible between the molecules (error bars indicating the range of variability). Inset, the same histograms in logarithmic scale (axes labels as for the main panel) showing (vertical black bars) the regions of work values where unfolding and refolding distributions are expected to cross each other by Bennett’s acceptance ratio method (Supplementary Information).

These results illustrate that when used in conjunction with an appropriate fluctuation theorem, nonequilibrium single-molecule force measurements can provide equilibrium information such as folding free energies, even if the process studied occurs under far-from-equilibrium conditions. The approach works using soft optical traps but is probably limited to processes that dissipate less than 100 k BT. Whether it can be extended to studies that use much stiffer atomic-force-microscope cantilevers to pull proteins27 is at present being examined in our laboratory. Finally, the initial and final states of molecular interactions such as ligand binding or macromolecular assembly usually do not correspond to measurable molecular extensions; in such cases, the approach as described cannot at present be applied.

METHODS

Sample preparation

The RNA molecules were prepared as previously described by ref. 16. Each DNA sequence corresponding to the three different RNAs was cloned separately into pBR322 vector between EcoRI and HindIII sites. A polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify a DNA sequence containing an upstream T7 promoter, the RNA sequence of interest and flanking DNA sequences corresponding to the ‘handles’. The handles correspond to a sequence of pBR322 (NCBI ID ‘J01749’) from nucleotides 3838 to 1 and from 29 to 629, respectively. The three RNA sequences were transcribed in vitro using T7 RNA polymerase28. Two DNA handles were synthesized by PCR. The DNA handle upstream of the RNA was biotinylated at the 3′-end, whereas a digoxigenin moiety was attached to the 5′-end of the other handle. The RNA and two DNA handles were annealed by heating samples to 85 °C, followed by a slow cooling down to room temperature. The RNA hairpin was pulled in 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.1, 1 mM EDTA buffer. The S15 three-helix junction and the mutant have been pulled in 62 mM KCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.8 buffer. In 4 mM MgCl2 the KCl concentration was adjusted to 50 mM to work at the same ionic strength as in the absence of Mg2+.

Work measurements

Work probability distributions were obtained from many force–extension curves for a given molecule and aligned to a worm-like chain curve that best fitted the force–extension data at forces below the range of forces where the molecule unfolds. This procedure minimizes the effect of machine drift on the measured work values. For the worm-like chain fits we used P ≈ 10 nm and P ≈ 1 nm for the persistence lengths of the DNA/RNA hybrid handles and ssRNA respectively. Work values were integrated along the range of extension: [355 nm, 380 nm] for the hairpin; [326 nm, 392 nm] for the S15 three-helix junction without magnesium (wild and mutant); and [337 nm, 398 nm] for the S15 three-helix junction with magnesium. The free-energy contributions from stretching the handles and the ssRNA were then obtained by numerical integration of the worm-like chain reference curves using the values for the persistence and contour lengths of the polymers. To estimate the free energy of unfolding at zero, , we subtract the free-energy contribution of the hybrid handles and ssRNA from the total reversible work across the transition, ΔGexp, by using the expression7,29: = ΔGexp − ΔGhandles − ΔGssRNA, where ΔGhandles,ΔGssRNA are the entropy loss contributions due to the stretching of the molecular handles attached on both sides of the hairpin and of the extended ssRNA, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Summary of results obtained for all molecules

| Molecule | σU | σR | ΔGexp | RU | RR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hairpin (1.5 pN s−1)* | 110.9 | 108.7 | 2.35 | 2.21 | 109.7 (0.2) | 107.4 (0.7) | 110.9 (0.2) | 109.1 (0.5) | 110.0 (0.2) | 62.5 (1.2) | 0.9 | 1.3 | 3.1 | 1.9 |

| Hairpin (7.5 pN s−1) | 113.8 | 106.6 | 2.63 | 2.84 | 110.3 (0.2) | 109.7 (0.7) | 110.9 (0.5) | 110.3 (0.5) | 110.3 (0.5) | 62.8 (1.5) | 3.5 | 3.7 | 0.98 | 1.10 |

| Hairpin (20 pN s−1) | 115.7 | 104.1 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 110.1 (0.2) | 110.2 (0.7) | 108.6 (0.2) | 109.4 (0.4) | 110.2 (0.6) | 62.9 (1.6) | 5.4 | 6.2 | 0.94 | 0.98 |

| S15 (wild, no Mg) | 191.3 | 145.9 | 11.3 | 2.9 | 158.7 (0.8) | 155.2 (1.4) | 149.3 (0.2) | 152.2 (0.7) | 154.1 (0.4) | 57.0 (1.5) | 36.3 | 9.1 | 1.75 | 0.46 |

| S15 (mutant, no Mg) | 176.5 | 153.4 | 10.6 | 2.1 | 156.0 (0.4) | 152.4 (5.0) | 155.7 (0.2) | 154.1 (0.3) | 157.9 (0.2) | 60.8 (1.5) | 18.6 | 4.5 | 3.02 | 0.49 |

| S15 (wild, Mg) | 256.4 | 190.3 | 12.2 | 5.0 | 213.0 (1.3) | 207.0 (4.0) | 199.8 (0.6) | 203.6 (2.0) | 205.5 (1.5) | 88.7 (2.5) | 50.9 | 15.2 | 1.46 | 0.82 |

and , σU and σR, and are the average total work, standard deviations and predictions obtained by using Jarzynski’s equality along the unfolding (U) and refolding (R) paths. is the estimate obtained by Hummer30, , which gives the leading correction to the linear response prediction, is the average of the estimates obtained by using Jarzynski’s equality along the unfolding and refolding paths , ΔGexp is our best estimate obtained by using the acceptance ratio method; is the final estimate for the unfolding free energy at zero force after subtracting the handles contribution, is the average dissipated work (for the analysis of the hairpin data we took ΔGexp = 110.3 for all pulling rates) and is a parameter that is equal to 1 for gaussian work distributions8. Statistical errors are given for Jarzynski’s equality and the crossing estimates. These were obtained using the bootstrap method. All work values (except: ) include the handle and RNA stretching contributions and are given in units of k BT at T = 298 K. In parentheses we indicate the errors in units of kBT.

Data for the RNA hairpin at 1.5 pN s−1 are also included for completion; however, at such low loading rates drift effects are very large and data are very noisy as revealed by the values of R U and and R R, which differ too much from 1.

Acknowledgments

We thank G. Hummer and A. Szabo for many discussions and G. E. Crooks, D. Chandler and J. Liphardt for a careful reading of the manuscript. F.R. was supported by the Spanish Research council and the Catalan Government (Distinció de la Generalitat). C.J. was supported by an NIH grant and the US Department of Energy. I.T. was supported by an NIH grant. C.B. was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information is linked to the online version of the paper at www.nature.com/nature.

References

- 1.Evans DJ, Cohen EG, Morriss GP. Probability of second law violations in shearing steady states. Phys Rev Lett. 1993;71:2401–2404. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.2401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gallavotti G, Cohen EGD. Dynamical ensembles in nonequilibrium statistical mechanics. Phys Rev Lett. 1995;74:2694–2697. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ciliberto S, Laroche C. An experimental test of the Gallavotti-Cohen fluctuation theorem. J Phys IV. 1998;8(Proc 6):215–220. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Evans DJ, Searles DJ. The fluctuation theorem. Adv Phys. 2002;51:1529–1585. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang GM, Sevick EM, Mittag E, Searles DJ, Evans DJ. Experimental demonstration of violations of the second law of thermodynamics for small systems and short timescales. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:050601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.050601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hummer G, Szabo A. Free-energy reconstruction from nonequilibrium single molecule experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3658–3661. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071034098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liphardt J, Dumont S, Smith SB, Tinoco I, Jr, Bustamante C. Equilibrium information from nonequilibrium measurements in an experimental test of the Jarzynski equality. Science. 2002;296:1832–1835. doi: 10.1126/science.1071152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritort F, Bustamante C, Tinoco I., Jr A two-state kinetic model for the unfolding of single molecules by mechanical force. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13544–13548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172525099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crooks GE. Entropy production fluctuation theorem and the nonequilibrium work relation for free-energy differences. Phys Rev E. 1999;60:2721–2726. doi: 10.1103/physreve.60.2721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith SB, Cui Y, Bustamante C. An optical-trap force transducer that operates by direct measurement of light momentum. Methods Enzymol. 2003;361:134–162. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(03)61009-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McManus MT, Petersen CP, Haines BB, Chen J, Sharp AP. Gene silencing using micro-RNA designed hairpins. RNA. 2002;8:842–850. doi: 10.1017/s1355838202024032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serganov A, et al. Role of conserved nucleotides in building the 16S rRNA binding site for ribosomal protein S15. J Mol Biol. 2002;305:785–803. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritort F. Work fluctuations, transient violations of the second law and free-energy recovery methods. Semin Poincaré. 2003;2:193–226. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jarzynski C. Nonequilibrium equality for free energy differences. Phys Rev Lett. 1997;78:2690–2693. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park S, Schulten K. Calculating potentials of mean force from steered molecular dynamics simulations. J Chem Phys. 2004;120:5946–5961. doi: 10.1063/1.1651473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liphardt J, Onoa B, Smith SB, Tinoco I, Jr, Bustamante C. Reversible unfolding of single RNA molecules by mechanical force. Science. 2001;292:733–737. doi: 10.1126/science.1058498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zuckerman DM, Woolf TB. Theory of systematic computational error in free energy differences. Phys Rev Lett. 2002;89:180602. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.89.180602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gore J, Ritort F, Bustamante C. Bias and error in estimates of equilibrium free-energy differences from nonequilibrium measurements. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:12564–12569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635159100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirts R, Bair E, Hooker G, Pande VS. Equilibrium free energies from nonequilibrium measurements using maximum likelihood methods. Phys Rev Lett. 2003;91:140601. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.140601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bennett CH. Efficient estimates of free energy differences from Monte Carlo data. J Comp Phys. 1976;22:245–268. [Google Scholar]

- 21.SantaLucia J, Jr, Hicks D. The thermodynamics of DNA structural motifs. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:415–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Robertus DJ, et al. Structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 3A resolution. Nature. 1974;250:546–551. doi: 10.1038/250546a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long DM, Uhlenbeck OC. Self-cleaving catalytic RNA. FASEB J. 1993;7:25–30. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.7.1.8422971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cate JH, Doudna JA. Metal binding sites in the major groove of a large ribozyme domain. Structure. 1996;4:1221–1229. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00129-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zuker M. Mfold web server for nucleic acid folding and hybridization predictions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3406–3415. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Turner, D. H. in Nucleic Acids: Structures, Properties and Functions (eds Bloomfield, D. A., Crothers, D. M. & Tinoco, I. Jr) Ch. 7 (Univ. Press, New York, 2000).

- 27.Carrion-Vazquez, M., et al. Protein nanomechanics studied by AFM single-molecule force spectroscopy. In Emerging Techniques in Biophysics (eds Arrondo, J. L. R. & Alonso, A.) (Biophys. Monogr. Ser., Springer, Heidelberg, in the press).

- 28.Milligan JF, Groebe DR, Witherell GW, Uhlenbeck OC. Oligoribonucleotide synthesis using T7 RNA polymerase and synthetic DNA templates. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:8783–8798. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.21.8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manosas M, Ritort F. Thermodynamic and kinetic aspects of RNA pulling experiments. Biophys J. 2005;88:3224–3242. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.045344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hummer G. Fast-growth thermodynamics integration: Error and efficiency analysis. J Chem Phys. 2001;114:7330–7337. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.