Abstract

OBJECTIVE—The purpose of this study was to investigate the therapeutic potential of the anti-CD2 mAb OX34 first with regard to bone protection in established rat adjuvant arthritis (AA) and secondly with regard to prevention of AA induction. METHODS—Established AA was treated with dexamethasone (1 mg/kg body weight) for two days plus OX34 mAb or control mAb over three days (2 mg and then 1 mg) starting at different time points of the disease. For prevention studies animals were injected as above with mAb before induction of AA. Arthritis score (AS), hindpaw thickness, and body weight were blindly measured three times per week. Flow cytometry and hindpaw radiography were performed at the end of the study (day 29). RESULTS—Treatment of early AA with OX34 mAb combined with dexamethasone but not dexamethasone plus control mAb dramatically suppressed established AA as assessed by AS and hind paw thickness (>65% and >80% reduction, respectively; p < 0.05). Most importantly, early treatment in the course of AA almost completely prevented bone destruction in established AA. When given before AA induction OX34 alone prevented the initiation of arthritis compared with controls (AS reduction 83-95%, p < 0.05). In addition, OX34 plus dexamethasone treatment resulted in depletion of CD4+ T cells but not CD8+ T cells. IL2R+ and CD45RC-(`memory') T cells were significantly reduced. CONCLUSIONS—Anti-CD2 mAb treatment prevents AA induction confirming the role of CD4+ T cells in the induction phase of AA. In addition, early OX34 plus dexamethasone treatment resulted in pronounced clinical improvement and joint protection. OX34 treatment therefore inhibits the initiation and the perpetuation of rat AA.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (142.7 KB).

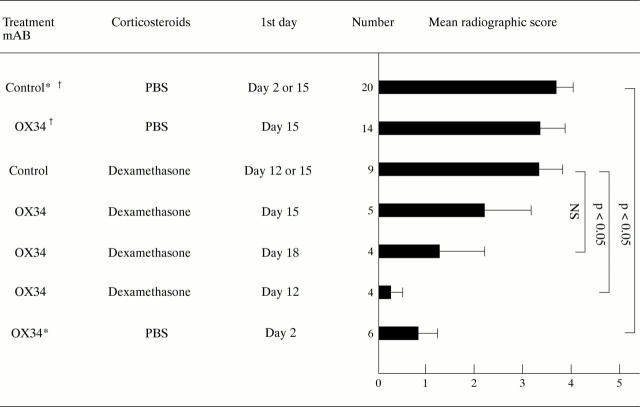

Figure 1 .

Influence of dexamethasone or OX34 treatment, or both, on radiographic bone destruction of AA rats. Indicated is the mean radiographic score of both hindpaws, the SEM for each treatment group, and the levels of significance. Radiographic scores of two groups of 14 rats receiving either OX34 or control mAb are included from a previous study (Hoffmann et al, unpublished data). All mAb treatments were started with 2 mg followed by 1 mg intraperitoneally per injection day, mAb were given over three consecutive days unless stated otherwise; dexamethasone was given intraperitoneally at 1 mg/kg body weight either for two consecutive days starting on day 12 or 18 or once on day 15. * = mAb given two days and one day before induction of AA and on the day of induction. † = mAb given on day 15, 17, 20, and 23 after induction of AA.

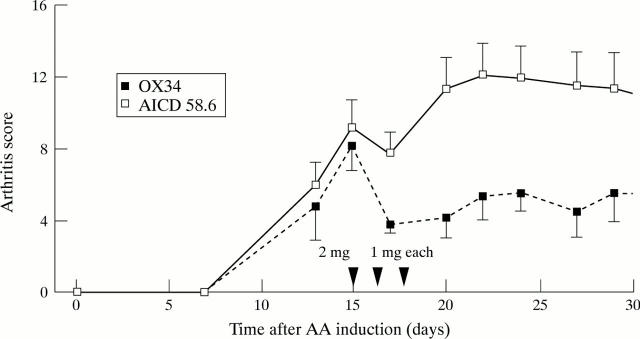

Figure 2 .

Amelioration of established AA by dexamethasone plus OX34 mAb therapy. Ten animals with established AA were randomised to intraperitoneal injections of OX34 (n = 5) or istotype matched control mAb (AICD58.6, n = 5) over three consecutive days starting with a loading dose of 2 mg followed by 1 mg each at indicated time points (arrows). Dexamethasone was given intraperitoneally on day 15 at a dose of 1mg/kg body weight. Arthritis score was measured by a blinded investigator at indicated time points. Shown are means (SEM), arrows indicate mAb injections.

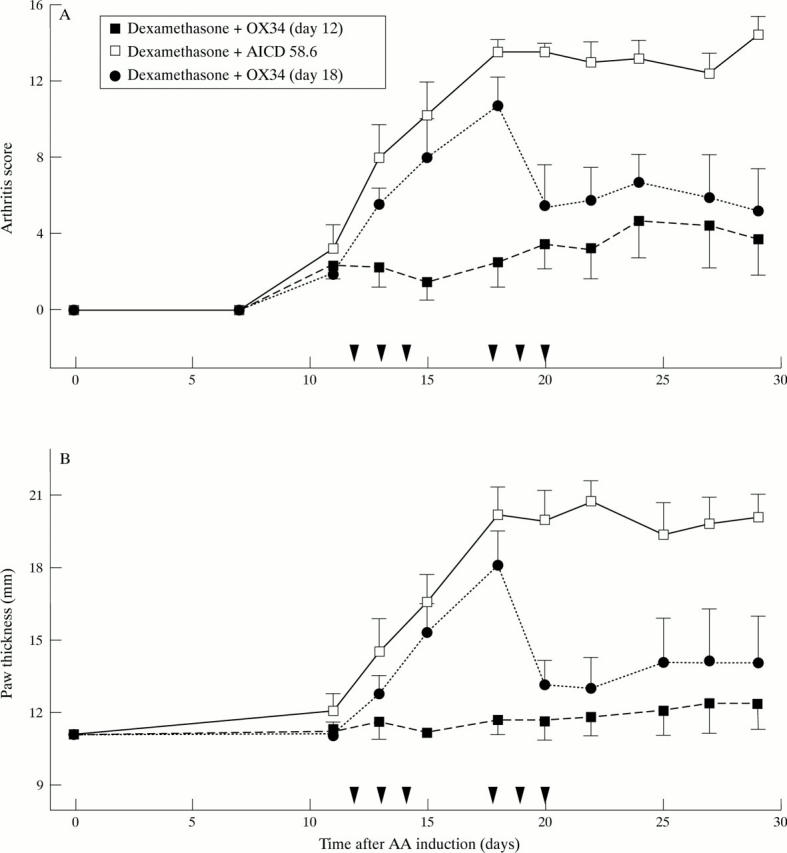

Figure 3 .

Marked suppression of established AA by early, repeated OX34 mAb injections plus a dexamethasone pulse over two days. Sixteen rats were injected with FCA and 12 rats developed AA by day 12 (AS ⩾ 2). These were randomised into three groups, four animals each, and received blindly either dexamethasone plus OX34 starting on day 12 (n = 4), dexamethasone plus control mAb (AICD 58.6) starting on day 12 (n = 4), or dexamethasone plus OX34 starting on day 18 (n = 4). PBS was given on those days when no mAb was injected (for example, day 12 to 14 for dexamethasone plus OX34). Dexamethasone diluted in PBS was given at a concentration of 1 mg/kg body weight on two consecutive days, mAbs were injected for three consecutive days starting with 2 mg followed by 1 mg per day. Arthritis score (A) and hindpaw thickness (B) were measured by a blinded investigator at indicated time points. Symbols and labelling as in figure 2.

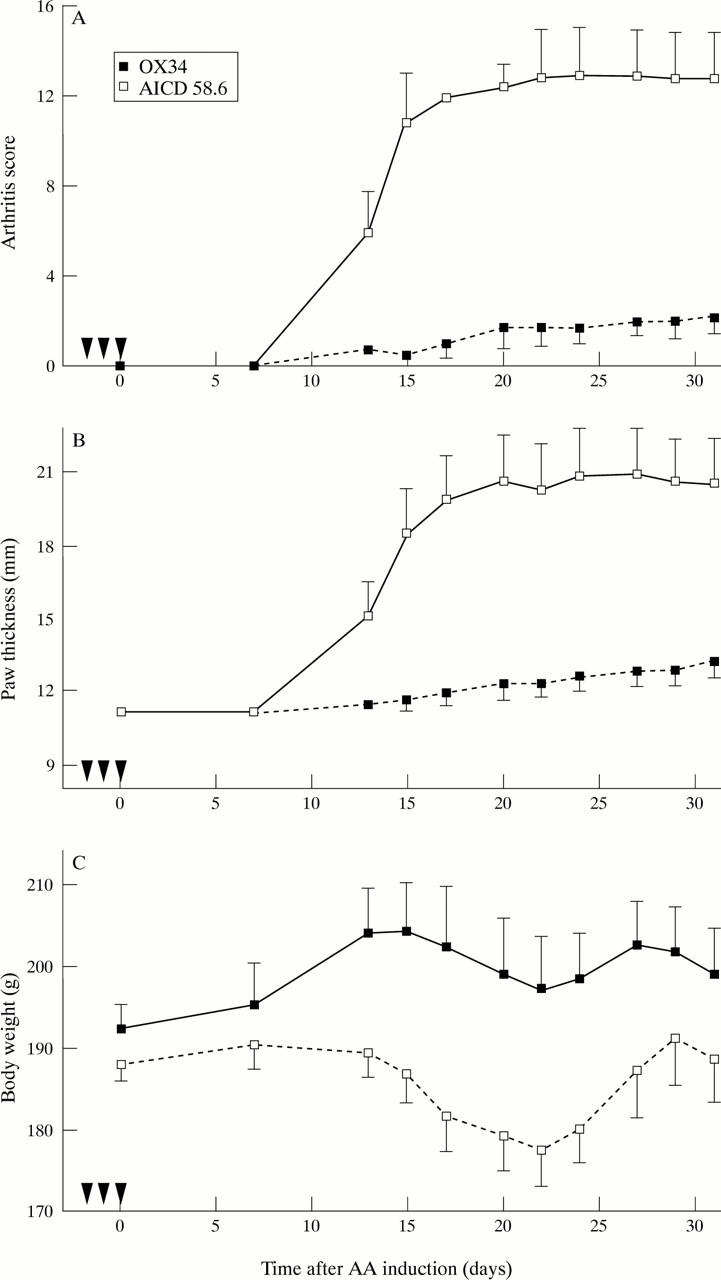

Figure 4 .

Prevention of AA induction by the anti-CD2 mAb OX34. Twelve animals were randomised to intraperitoneal administration of OX34 (n = 6) or istotype matched control mAb (AICD 58.6, n = 6) as in figure 3 before AA induction. Arthritis score (A), hind paw thickness (B), and body weight (C) was measured by a blinded investigator at indicated time points. Symbols and labelling as in figure 2.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alarcón G. S., López-Méndez A., Walter J., Boerbooms A. M., Russell A. S., Furst D. E., Rau R., Drosos A. A., Bartolucci A. A. Radiographic evidence of disease progression in methotrexate treated and nonmethotrexate disease modifying antirheumatic drug treated rheumatoid arthritis patients: a meta-analysis. J Rheumatol. 1992 Dec;19(12):1868–1873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arvieux J., Jefferies W. A., Paterson D. J., Williams A. F., Green J. R. Monoclonal antibodies against a rat leucocyte antigen block antigen-induced T-cell responses via an effect on accessory cells. Immunology. 1986 Jul;58(3):337–342. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow A. K., Like A. A. Anti-CD2 monoclonal antibodies prevent spontaneous and adoptive transfer of diabetes in the BB/Wor rat. Am J Pathol. 1992 Nov;141(5):1043–1051. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gückel B., Berek C., Lutz M., Altevogt P., Schirrmacher V., Kyewski B. A. Anti-CD2 antibodies induce T cell unresponsiveness in vivo. J Exp Med. 1991 Nov 1;174(5):957–967. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.5.957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halloran M. M., Szekanecz Z., Barquin N., Haines G. K., Koch A. E. Cellular adhesion molecules in rat adjuvant arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1996 May;39(5):810–819. doi: 10.1002/art.1780390514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hershkoviz R., Gilat D., Miron S., Mekori Y. A., Aderka D., Wallach D., Vlodavsky I., Cohen I. R., Lider O. Extracellular matrix induces tumour necrosis factor-alpha secretion by an interaction between resting rat CD4+ T cells and macrophages. Immunology. 1993 Jan;78(1):50–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirahara H., Tsuchida M., Watanabe T., Haga M., Matsumoto Y., Abo T., Eguchi S. Long-term survival of cardiac allografts in rats treated before and after surgery with monoclonal antibody to CD2. Transplantation. 1995 Jan 15;59(1):85–90. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199501150-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann J. C., Herklotz C., Zeidler H., Bayer B., Westermann J. Anti-CD2 (OX34) MoAb treatment of adjuvant arthritic rats: attenuation of established arthritis, selective depletion of CD4+ T cells, and CD2 down-modulation. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997 Oct;110(1):63–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4881385.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issekutz A. C., Issekutz T. B. Quantitation and kinetics of polymorphonuclear leukocyte and lymphocyte accumulation in joints during adjuvant arthritis in the rat. Lab Invest. 1991 May;64(5):656–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issekutz A. C., Meager A., Otterness I., Issekutz T. B. The role of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and IL-1 in polymorphonuclear leucocyte and T lymphocyte recruitment to joint inflammation in adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1994 Jul;97(1):26–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.1994.tb06574.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S., Toyka K., Hartung H. P. Suppression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in Lewis rats by antibodies against CD2. Eur J Immunol. 1995 May;25(5):1391–1398. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830250538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohashi O., Pearson C. M., Tamaoki N., Tanaka A., Shimamura K., Ozawa A., Kotani S., Saito M., Hioki K. Role of thymus for N-acetyl muramyl-L-alanyl-D-isoglutamine-induced polyarthritis and granuloma formation in euthymic and athymic nude rats or in neonatally thymectomized rats. Infect Immun. 1981 Feb;31(2):758–766. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.2.758-766.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Méndez A., Daniel W. W., Reading J. C., Ward J. R., Alarcón G. S. Radiographic assessment of disease progression in rheumatoid arthritis patients enrolled in the cooperative systematic studies of the rheumatic diseases program randomized clinical trial of methotrexate, auranofin, or a combination of the two. Arthritis Rheum. 1993 Oct;36(10):1364–1369. doi: 10.1002/art.1780361006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meacock S. C., Brandon D. R., Billingham M. E. Arthritis in Lewis rats induced by the non-immunogenic adjuvant CP20961: an immunohistochemical analysis of the developing disease. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Oct;53(10):653–658. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.10.653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peacock D. J., Banquerigo M. L., Brahn E. Angiogenesis inhibition suppresses collagen arthritis. J Exp Med. 1992 Apr 1;175(4):1135–1138. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.4.1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrí C., Morante M. P., Castellote C., Franch A., Castell M. Treatment with an anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody strongly ameliorates established rat adjuvant arthritis. Clin Exp Immunol. 1996 Feb;103(2):273–278. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1996.d01-624.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelegrí C., Paz Morante M., Castellote C., Castell M., Franch A. Administration of a nondepleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody (W3/25) prevents adjuvant arthritis, even upon rechallenge: parallel administration of a depleting anti-CD8 monoclonal antibody (OX8) does not modify the effect of W3/25. Cell Immunol. 1995 Oct 15;165(2):177–182. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed J. C., Tadmori W., Kamoun M., Koretzky G., Nowell P. C. Suppression of interleukin 2 receptor acquisition by monoclonal antibodies recognizing the 50 KD protein associated with the sheep erythrocyte receptor on human T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1985 Mar;134(3):1631–1639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaman W. E., Eriksson E., Dobrow R., Imboden J. B. Inositol trisphosphate is generated by a rat natural killer cell tumor in response to target cells or to crosslinked monoclonal antibody OX-34: possible signaling role for the OX-34 determinant during activation by target cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987 Jun;84(12):4239–4243. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.12.4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taurog J. D., Argentieri D. C., McReynolds R. A. Adjuvant arthritis. Methods Enzymol. 1988;162:339–355. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)62089-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinblatt M. E., Polisson R., Blotner S. D., Sosman J. L., Aliabadi P., Baker N., Weissman B. N. The effects of drug therapy on radiographic progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Results of a 36-week randomized trial comparing methotrexate and auranofin. Arthritis Rheum. 1993 May;36(5):613–619. doi: 10.1002/art.1780360507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann J., Nagahori Y., Walter S., Heerwagen C., Miyasaka M., Pabst R. B and T lymphocyte subsets enter peripheral lymph nodes and Peyer's patches without preference in vivo: no correlation occurs between their localization in different types of high endothelial venules and the expression of CD44, VLA-4, LFA-1, ICAM-1, CD2 or L-selectin. Eur J Immunol. 1994 Oct;24(10):2312–2316. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. O., Mason L. J., Feldmann M., Maini R. N. Synergy between anti-CD4 and anti-tumor necrosis factor in the amelioration of established collagen-induced arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Mar 29;91(7):2762–2766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshino S., Schlipköter E., Kinne R., Hünig T., Emmrich F. Suppression and prevention of adjuvant arthritis in rats by a monoclonal antibody to the alpha/beta T cell receptor. Eur J Immunol. 1990 Dec;20(12):2805–2808. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zvaifler N. J., Firestein G. S. Pannus and pannocytes. Alternative models of joint destruction in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994 Jun;37(6):783–789. doi: 10.1002/art.1780370601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Merwe P. A., McPherson D. C., Brown M. H., Barclay A. N., Cyster J. G., Williams A. F., Davis S. J. The NH2-terminal domain of rat CD2 binds rat CD48 with a low affinity and binding does not require glycosylation of CD2. Eur J Immunol. 1993 Jun;23(6):1373–1377. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]