Abstract

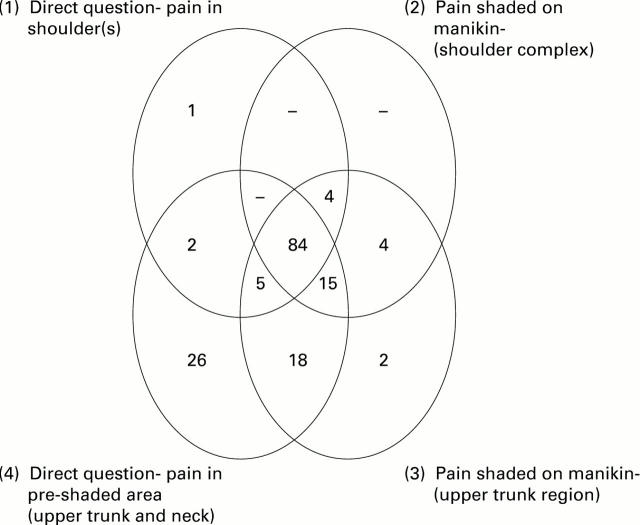

OBJECTIVE—To compare estimates of the occurrence of shoulder pain according to (a) different approaches to defining `shoulder' and (b) restricting the definition to only include those with associated disability. METHODS—A postal questionnaire survey was sent to a sample of 500 patients registered with a general practice in south Manchester. After additional mailings to non-responders, 312 questionnaires were returned (66% adjusted response rate). Four definitions of shoulder pain were used to estimate the occurrence of symptoms derived from answers to the questionnaire. Two were based on questions asking directly about pain in the shoulder and the upper trunk and neck region respectively and two were based on markings on a pain drawing in the shoulder complex and the upper trunk respectively. To determine the occurrence of disabling shoulder pain responders were subsequently approached for interview. Of the responders, 232 (74%) were successfully interviewed. Those indicating that they were suffering from `current' shoulder symptoms, pain on the day of interview, were asked to complete a short, 23 item, questionnaire enquiring about disability in daily living associated with such symptoms. RESULTS—In total 160 (51%) people reported shoulder pain according to at least one definition. This one month period prevalence ranged from 31% to 48% across the four definitions with the lowest estimate being for the question asking directly about shoulder symptoms. In total 84 people (27% of all respondents) answered positively to all four definitions. Only seven people who answered positively when asked directly about shoulder pain did not indicate symptoms on the pain drawing in the shoulder complex. By contrast 65 (30%) of those answering negatively to the direct question about shoulder pain indicated symptoms on the pain drawing in the upper trunk region or answered positively to the direct question about pain in the upper trunk or neck region. However only 19 (9%) of those answering negatively to the direct question indicated symptoms in the shoulder complex on the pain drawing, compared with 38 (18%) indicating symptoms in the upper trunk region and 59 (27%) symptoms in the upper trunk and neck region. Limiting the definition to only include current symptoms with some associated disability (at least one item on the disability questionnaire being answered positively) restricted the point prevalence to 20% (n=46). CONCLUSIONS—Using a pain drawing based definition with case ascertainment restricted to an area in and around the shoulder complex is recommended for surveys assessing the occurrence of shoulder symptoms in the general population. To solve the problem of the poor specificity associated with symptom based definitions it is useful to incorporate an additional classification to restrict the definition to more disabling problems.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (116.2 KB).

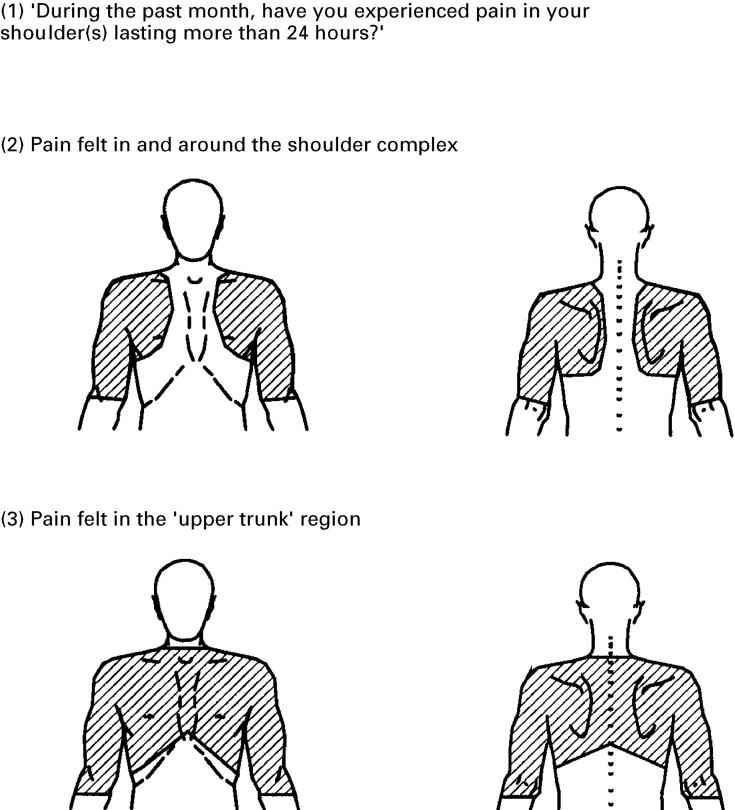

Figure 1 .

Case definitions of shoulder pain used in the cross sectional survey.

Figure 2 .

Case definition of shoulder pain used in the cross sectional survey.

Figure 3 .

Overlap of definitions of shoulder pain from cross sectional survey.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andersson H. I., Ejlertsson G., Leden I., Rosenberg C. Chronic pain in a geographically defined general population: studies of differences in age, gender, social class, and pain localization. Clin J Pain. 1993 Sep;9(3):174–182. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199309000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjelle A. Epidemiology of shoulder problems. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol. 1989 Dec;3(3):437–451. doi: 10.1016/s0950-3579(89)80003-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchbinder R., Goel V., Bombardier C., Hogg-Johnson S. Classification systems of soft tissue disorders of the neck and upper limb: do they satisfy methodological guidelines? J Clin Epidemiol. 1996 Feb;49(2):141–149. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(95)00519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard M. D., Hazleman R., Hazleman B. L., King R. H., Reiss B. B. Shoulder disorders in the elderly: a community survey. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Jun;34(6):766–769. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croft P., Pope D., Zonca M., O'Neill T., Silman A. Measurement of shoulder related disability: results of a validation study. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Aug;53(8):525–528. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.8.525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham L. S., Kelsey J. L. Epidemiology of musculoskeletal impairments and associated disability. Am J Public Health. 1984 Jun;74(6):574–579. doi: 10.2105/ajph.74.6.574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasvold T., Johnsen R. Headache and neck or shoulder pain--frequent and disabling complaints in the general population. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1993 Sep;11(3):219–224. doi: 10.3109/02813439308994834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsson L., Lindgärde F., Manthorpe R. The commonest rheumatic complaints of over six weeks' duration in a twelve-month period in a defined Swedish population. Prevalences and relationships. Scand J Rheumatol. 1989;18(6):353–360. doi: 10.3109/03009748909102096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locker D., Slade G. D., Leake J. L. The response rate problem in oral health surveys of older adults in Ontario. Can J Public Health. 1990 May-Jun;81(3):210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nygren A., Berglund A., von Koch M. Neck-and-shoulder pain, an increasing problem. Strategies for using insurance material to follow trends. Scand J Rehabil Med Suppl. 1995;32:107–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohlund C., Eek C., Palmbald S., Areskoug B., Nachemson A. Quantified pain drawing in subacute low back pain. Validation in a nonselected outpatient industrial sample. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1996 May 1;21(9):1021–1031. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199605010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papageorgiou A. C., Croft P. R., Ferry S., Jayson M. I., Silman A. J. Estimating the prevalence of low back pain in the general population. Evidence from the South Manchester Back Pain Survey. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1995 Sep 1;20(17):1889–1894. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope D. P., Croft P. R., Pritchard C. M., Macfarlane G. J., Silman A. J. The frequency of restricted range of movement in individuals with self-reported shoulder pain: results from a population-based survey. Br J Rheumatol. 1996 Nov;35(11):1137–1141. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/35.11.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope D., Croft P. Surveys using general practice registers: who are the non-responders? J Public Health Med. 1996 Mar;18(1):6–12. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangfort E. Clinical aspects of neck-and-shoulder pain. Scand J Rehabil Med Suppl. 1995;32:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takala J., Sievers K., Klaukka T. Rheumatic symptoms in the middle-aged population in southwestern Finland. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1982;47:15–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]