Abstract

OBJECTIVE—In aseptic loosening, a heavy macrophage response to biomaterial wear particles is commonly found in arthroplasty tissues. The aim of this study was to discover if these cells contribute to the bone resorption of aseptic loosening by differentiating into osteoclasts. METHODS—Macrophages were isolated from the pseudocapsule and pseudomembrane of loose cemented and uncemented hip arthroplasties at the time of revision surgery and then co-cultured on glass coverslips and dentine slices with UMR 106 rat osteoblast-like cells, both in the presence and absence of 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 [1,25(OH)2D3]. Macrophages isolated from the synovial membrane of patients with osteoarthritis (OA) undergoing hip replacements were similarly studied as a control group. RESULTS—After 24 hours incubation, most cells isolated from the above periprosthetic tissues strongly expressed macrophage (CD11b, CD14) but not osteoclast markers. However, after 14 days incubation, numerous multinucleated cells showing the phenotypic features of osteoclasts (that is, positive for tartrate resistant acid phosphatase, the vitronectin receptor, and capable of extensive lacunar resorption) formed in co-cultures of arthroplasty derived macrophages and UMR 106 cells, in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. The addition of an antibody to macrophage colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) considerably reduced macrophage-osteoclast differentiation and hence the lacunar resorption seen in these co-cultures. In contrast, OA synovial macrophage/UMR 106 co-cultures showed little or no evidence of macrophage-osteoclast differentiation and this was only seen when human M-CSF was added to the co-cultures. CONCLUSION—This is the first report showing that human macrophages isolated directly from periprosthetic tissues surrounding loosened implants can differentiate into multinucleated cells showing all the functional and cytochemical characteristics of osteoclasts. In contrast with other macrophage populations, exogenous M-CSF is not required for this to occur. In the context of the heavy macrophage response to wear particles in periprosthetic tissues macrophage-osteoclast differentiation may represent an important cellular mechanism whereby osteolysis is effected in aseptic loosening.

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (191.4 KB).

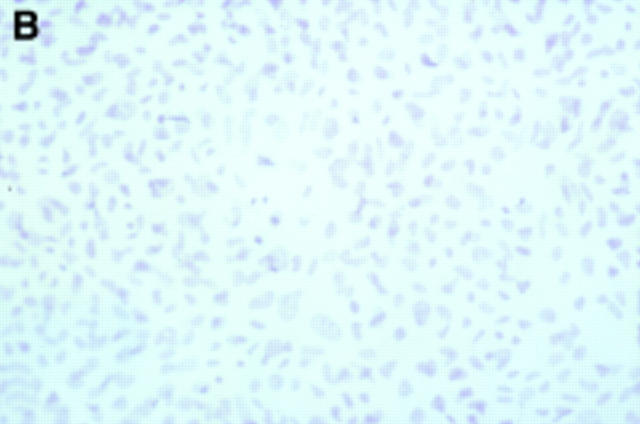

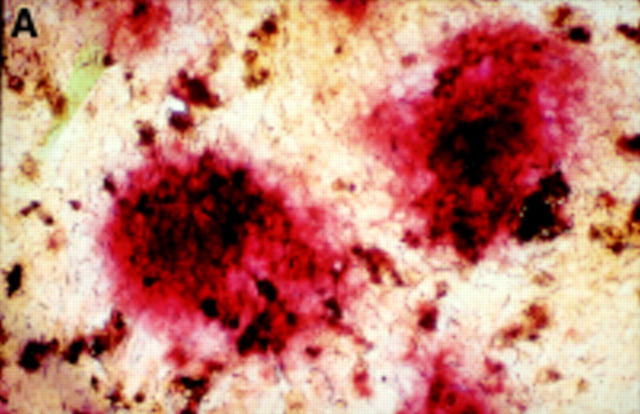

Figure 1 .

Twenty four hour culture of arthroplasty derived macrophages incubated with UMR 106 cells (in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3) stained by an indirect immunoperoxidase technique with monoclonal antibodies.(A) GRS 1 (anti-CD14) and (B) 23C6 (anti- VNR), showing reaction for CD14 (arrows) but not VNR on isolated cells. This indicates that these cells express a monocyte/macrophage but not osteoclast immunophenotype. (Original magnification × 200).

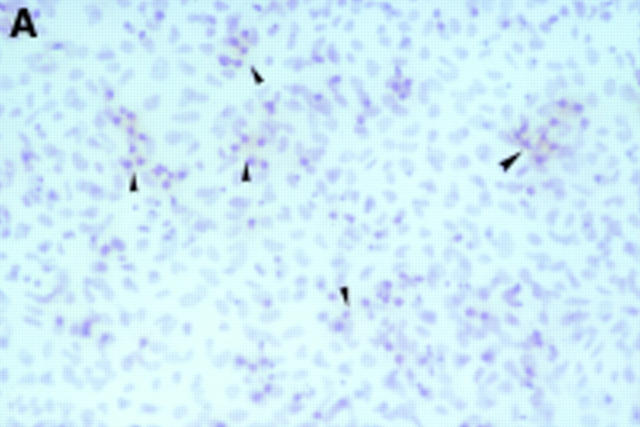

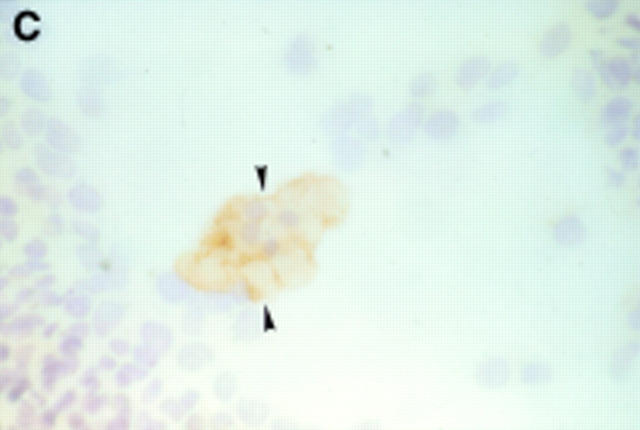

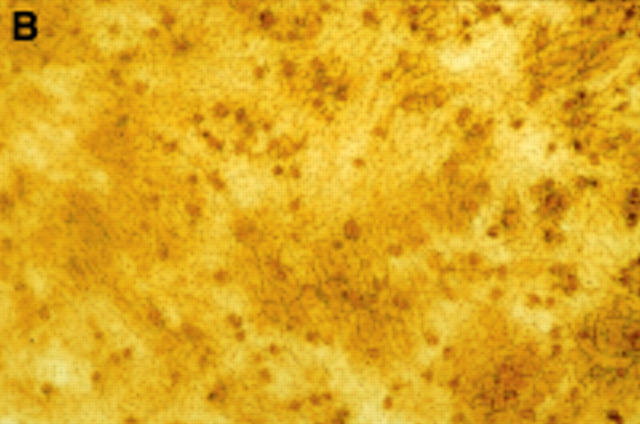

Figure 2 .

Seven day culture of arthroplasty derived macrophages incubated with UMR 106 cells showing: (A) clusters of TRAP positive cells in the presence of 1,25(OH)2D3. (Original magnification × 200). (B) negative control for the TRAP staining (that is, in the absence of 1,25(OH)2D3. (Original magnification × 200). (C) A VNR positive multinucleated cell (arrow heads). (Original magnification × 400).

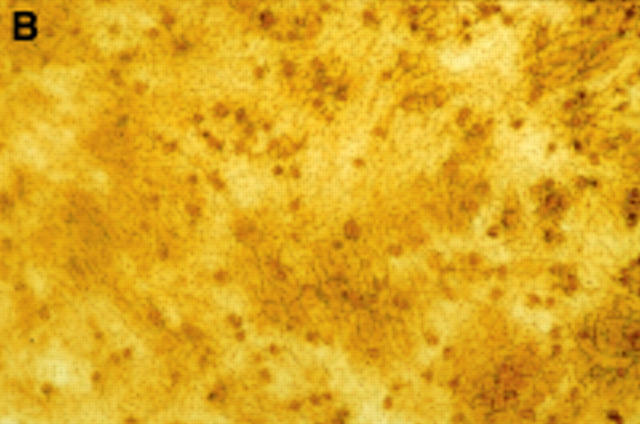

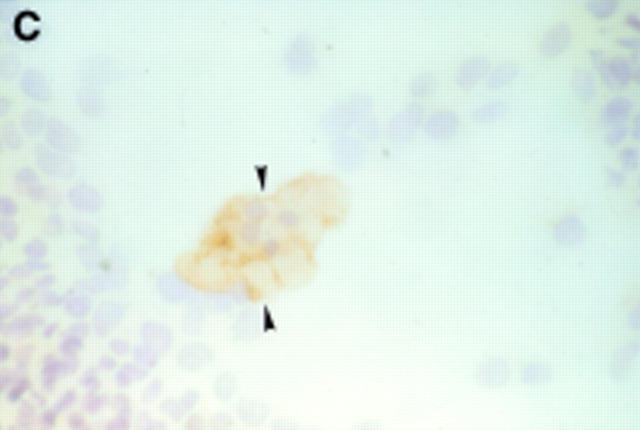

Figure 3 .

(A) Fourteen day culture of arthroplasty derived macrophages incubated with UMR 106 cells on dentine slices. The cells have been removed to reveal evidence of lacunar resorption with the formation of numerous well defined resorption pits. (Black bar = 100 µm). (B) A high power view of individual resorption pits. (Black bar = 100 µm).

Figure 4 .

Effect of neutralising anti-M-CSF antibody on the mean number of lacunar pits formed on dentine slices from co-cultures of arthroplasty derived macrophages from case numbers 6 and 7. Results are expressed as mean (SD). Levels of significance using Student's paired t test: (*); p=0.024 and (***); p=0.00092.

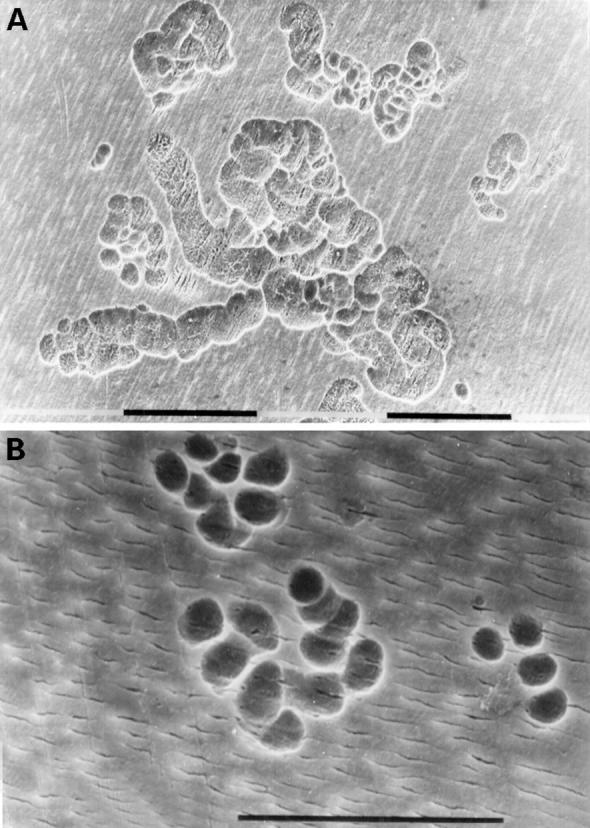

Figure 5 .

Proposed cellular and humoral mechanism whereby human wear particle induced foreign body macrophages in the periprosthetic tissues differentiate into osteoclastic bone resorbing cells.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amstutz H. C., Campbell P., Kossovsky N., Clarke I. C. Mechanism and clinical significance of wear debris-induced osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992 Mar;(276):7–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J., Bulstrode C. J. Resorption of bone by inflammatory cells derived from the joint capsule of hip arthroplasties. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Jan;74(1):57–62. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B1.1732267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J., Horton M. A., McGee J. O. New sites of cellular vitronectin receptor immunoreactivity detected with osteoclast-reacting monoclonal antibodies 13C2 and 23C6. Bone Miner. 1990 Jan;8(1):7–22. doi: 10.1016/0169-6009(91)90136-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanasou N. A., Quinn J. Immunophenotypic differences between osteoclasts and macrophage polykaryons: immunohistological distinction and implications for osteoclast ontogeny and function. J Clin Pathol. 1990 Dec;43(12):997–1003. doi: 10.1136/jcp.43.12.997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyde A., Ali N. N., Jones S. J. Resorption of dentine by isolated osteoclasts in vitro. Br Dent J. 1984 Mar 24;156(6):216–220. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4805313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullough P. G., DiCarlo E. F., Hansraj K. K., Neves M. C. Pathologic studies of total joint replacement. Orthop Clin North Am. 1988 Jul;19(3):611–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers T. J., Horton M. A. Failure of cells of the mononuclear phagocyte series to resorb bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 1984 Sep;36(5):556–558. doi: 10.1007/BF02405365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix R., Cecchini M. G., Fleisch H. Macrophage colony stimulating factor restores in vivo bone resorption in the op/op osteopetrotic mouse. Endocrinology. 1990 Nov;127(5):2592–2594. doi: 10.1210/endo-127-5-2592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa Y., Quinn J. M., Sabokbar A., McGee J. O., Athanasou N. A. The human osteoclast precursor circulates in the monocyte fraction. Endocrinology. 1996 Sep;137(9):4058–4060. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.9.8756585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujikawa Y., Sabokbar A., Neale S., Athanasou N. A. Human osteoclast formation and bone resorption by monocytes and synovial macrophages in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996 Nov;55(11):816–822. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.11.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Chin R. C., Chiou S. S., Schurman D. J., Woolson S. T., Masada M. P. A clinical-pathologic-biochemical study of the membrane surrounding loosened and nonloosened total hip arthroplasties. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989 Jul;(244):182–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman S. B., Chin R. C. Prostaglandin E2 levels in the membrane surrounding bulk and particulate polymethylmethacrylate in the rabbit tibia. A preliminary study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990 Aug;(257):305–309. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris W. H. Osteolysis and particle disease in hip replacement. A review. Acta Orthop Scand. 1994 Feb;65(1):113–123. doi: 10.3109/17453679408993734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris W. H. The problem is osteolysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1995 Feb;(311):46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz S. M., Purdon M. A. Mechanisms of cellular recruitment in aseptic loosening of prosthetic joint implants. Calcif Tissue Int. 1995 Oct;57(4):301–305. doi: 10.1007/BF00298886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton M. A., Lewis D., McNulty K., Pringle J. A., Chambers T. J. Monoclonal antibodies to osteoclastomas (giant cell bone tumors): definition of osteoclast-specific cellular antigens. Cancer Res. 1985 Nov;45(11 Pt 2):5663–5669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiranek W. A., Machado M., Jasty M., Jevsevar D., Wolfe H. J., Goldring S. R., Goldberg M. J., Harris W. H. Production of cytokines around loosened cemented acetabular components. Analysis with immunohistochemical techniques and in situ hybridization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993 Jun;75(6):863–879. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199306000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadoya Y., al-Saffar N., Kobayashi A., Revell P. A. The expression of osteoclast markers on foreign body giant cells. Bone Miner. 1994 Nov;27(2):85–96. doi: 10.1016/s0169-6009(08)80211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. J., Rubash H. E., Wilson S. C., D'Antonio J. A., McClain E. J. A histologic and biochemical comparison of the interface tissues in cementless and cemented hip prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1993 Feb;(287):142–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreutz M., Andreesen R. Induction of human monocyte to macrophage maturation in vitro by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 1990 Dec 15;76(12):2457–2461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lennox D. W., Schofield B. H., McDonald D. F., Riley L. H., Jr A histologic comparison of aseptic loosening of cemented, press-fit, and biologic ingrowth prostheses. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987 Dec;(225):171–191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minkin C. Bone acid phosphatase: tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase as a marker of osteoclast function. Calcif Tissue Int. 1982 May;34(3):285–290. doi: 10.1007/BF02411252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray D. W., Rushton N. Macrophages stimulate bone resorption when they phagocytose particles. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990 Nov;72(6):988–992. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey R., Quinn J., Joyner C., Murray D. W., Triffitt J. T., Athanasou N. A. Arthroplasty implant biomaterial particle associated macrophages differentiate into lacunar bone resorbing cells. Ann Rheum Dis. 1996 Jun;55(6):388–395. doi: 10.1136/ard.55.6.388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Partridge N. C., Alcorn D., Michelangeli V. P., Kemp B. E., Ryan G. B., Martin T. J. Functional properties of hormonally responsive cultured normal and malignant rat osteoblastic cells. Endocrinology. 1981 Jan;108(1):213–219. doi: 10.1210/endo-108-1-213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J. M., McGee J. O., Athanasou N. A. Cellular and hormonal factors influencing monocyte differentiation to osteoclastic bone-resorbing cells. Endocrinology. 1994 Jun;134(6):2416–2423. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.6.8194468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J. M., Sabokbar A., Athanasou N. A. Cells of the mononuclear phagocyte series differentiate into osteoclastic lacunar bone resorbing cells. J Pathol. 1996 May;179(1):106–111. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199605)179:1<106::AID-PATH535>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn J., Joyner C., Triffitt J. T., Athanasou N. A. Polymethylmethacrylate-induced inflammatory macrophages resorb bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1992 Sep;74(5):652–658. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.74B5.1527108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell P. A. Tissue reactions to joint prostheses and the products of wear and corrosion. Curr Top Pathol. 1982;71:73–101. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-68382-4_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigby W. F. The immunobiology of vitamin D. Immunol Today. 1988 Feb;9(2):54–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth P., Stanley E. R. The biology of CSF-1 and its receptor. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;181:141–167. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-77377-8_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Hoikka V., Eskola A., Konttinen Y. T., Paavilainen T., Tallroth K. Aggressive granulomatous lesions in cementless total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990 Nov;72(6):980–984. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B6.2246301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santavirta S., Konttinen Y. T., Bergroth V., Eskola A., Tallroth K., Lindholm T. S. Aggressive granulomatous lesions associated with hip arthroplasty. Immunopathological studies. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990 Feb;72(2):252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Tanaka S., Murakami H., Owan I., Tamura T., Suda T. Postmitotic osteoclast precursors are mononuclear cells which express macrophage-associated phenotypes. Dev Biol. 1994 May;163(1):212–221. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi N., Yamana H., Yoshiki S., Roodman G. D., Mundy G. R., Jones S. J., Boyde A., Suda T. Osteoclast-like cell formation and its regulation by osteotropic hormones in mouse bone marrow cultures. Endocrinology. 1988 Apr;122(4):1373–1382. doi: 10.1210/endo-122-4-1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S., Takahashi N., Udagawa N., Tamura T., Akatsu T., Stanley E. R., Kurokawa T., Suda T. Macrophage colony-stimulating factor is indispensable for both proliferation and differentiation of osteoclast progenitors. J Clin Invest. 1993 Jan;91(1):257–263. doi: 10.1172/JCI116179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Udagawa N., Takahashi N., Akatsu T., Tanaka H., Sasaki T., Nishihara T., Koga T., Martin T. J., Suda T. Origin of osteoclasts: mature monocytes and macrophages are capable of differentiating into osteoclasts under a suitable microenvironment prepared by bone marrow-derived stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Sep;87(18):7260–7264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida H., Hayashi S., Kunisada T., Ogawa M., Nishikawa S., Okamura H., Sudo T., Shultz L. D., Nishikawa S. The murine mutation osteopetrosis is in the coding region of the macrophage colony stimulating factor gene. Nature. 1990 May 31;345(6274):442–444. doi: 10.1038/345442a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]