Abstract

OBJECTIVE—To determine whether induced mast cell activation/degranulation in rheumatoid synovial explants modulates the production of prostaglandin E (PGE2), and the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) collagenase 1, gelatinase A, and stromelysin 1. METHODS—Synovial explant cultures were treated either with rabbit IgG anti-human IgE as a mast cell (MC) secretagogue or with non-immune rabbit IgG as controls. After 20 hours conditioned medium was assayed for the release of MC tryptase, PGE2, collagenase 1, gelatinase A, and stromelysin 1 using radioimmunoassay, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay, western blot, and zymogram techniques; tissue explants were examined immunohistologically for the relative distributions of MC tryptase, collagenase 1, and stromelysin 1. RESULTS—Over a 20 hour incubation period the MC secretagogue treated explants showed a significant increase in the quantities of released tryptase and PGE2 compared with controls. By contrast, the three MMPs showed variable values between experiments in response to MC activation; no reproducible trend of either an increased or decreased production of each MMP over control values was evident. Each MMP initially appeared as an inactive precursor form; collagenase 1 and stromelysin 1 were more effectively processed to active forms in the MC activated cultures. Immunolocalisation studies of MC activated explants showed that areas of extracellular tryptase were commonly associated with the local production of both collagenase 1 and stromelysin 1. CONCLUSION—MC degranulation induced artificially in rheumatoid synovial explant cultures consistently resulted in an increased production of PGE2 but had variable effects on the quantification of released collagenase 1, gelatinase A, and stromelysin 1. Such observations support the concept that activated synovial MCs within their native environment stimulate the production of non-MC derived PGE2 and may contribute to the regulation and processing of specific MMPs; both aspects represent important components of the inflammatory and degradative processes of the rheumatoid lesion. Keywords: mast cells; matrix metalloproteinases; prostaglandin E2; rheumatoid synovium

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (226.8 KB).

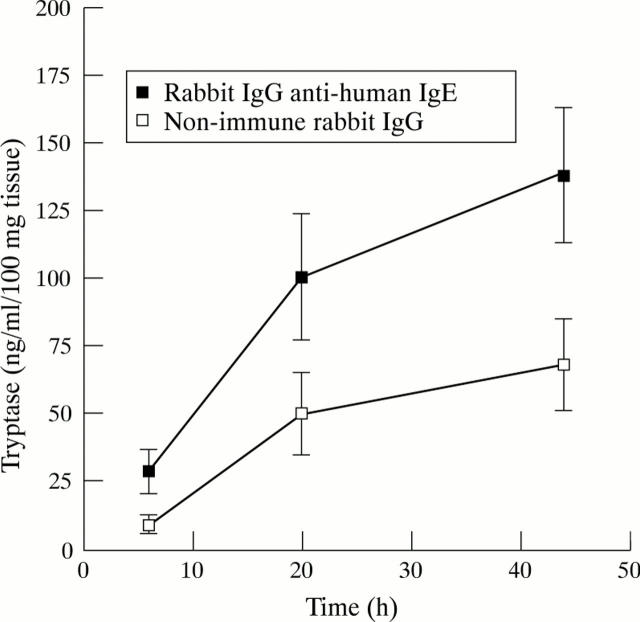

Figure 1 .

Cumulative data for tryptase release from rheumatoid synovial explant cultures treated with MC secretagogue or non-immune rabbit IgG over 44 hours. Data points represent mean (SEM) values from five different specimens.

Figure 2 .

Cumulative data for PGE2 release from rheumatoid synovial explant cultures treated with MC secretagogue or non-immune rabbit IgG. Data points represent mean (SEM) values from four different specimens.

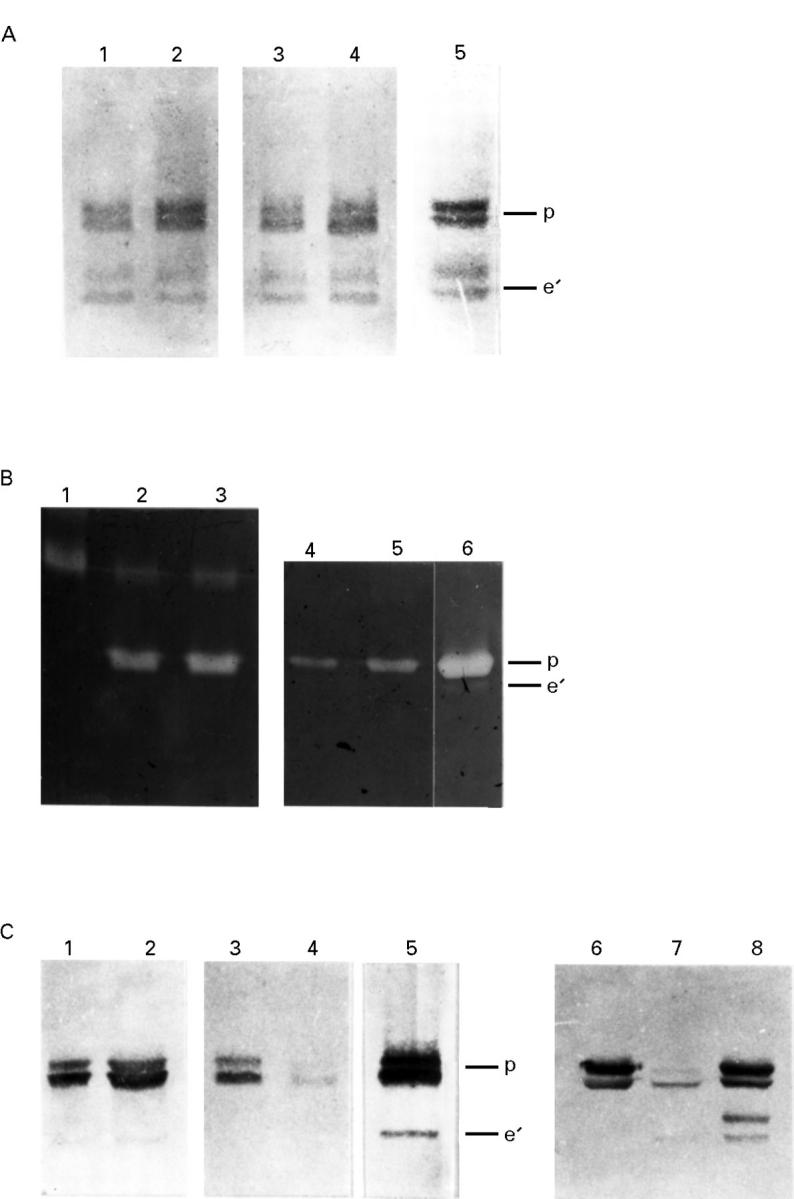

Figure 3 .

Western blot and zymogram analyses of collagenase 1, gelatinase A, and stromelysin 1 released from rheumatoid synovial explant cultures treated with and without MC secretagogue. (A) Collagenase 1. Western blot analysis of the precursor (p) and active (e') forms of collagenase 1 are shown by the enzyme standard (lane 5). Collagenase 1 released from control cultures is shown after 20 hours (lane 1) and 44 hours (lane 3) for comparison with similar secretagogue treated cultures at 20 hours (lane 2) and 44 hours (lane 4). Note the modest increase in the amounts of precursor enzyme (52 kDa) from the secretagogue treated cultures (lanes 2 and 4) compared with controls, and the presence of active enzyme (43 and 41 kDa) in both the 20 and 44 hour samples. (B) Gelatinase A. Zymography of the precursor (p) and active (e') forms of gelatinase A are shown by the enzyme standard (lane 6); and progelatinase B standard shown on lane 1. Gelatinase A in precursor form released from control cultures after 20 hours is shown in lanes 2 and 4, for comparison with similar secretagogue treated cultures shown in lanes 3 and 5. The precursor form of gelatinase B is also seen in lanes 2 and 3, but no evidence for activation or processing was observed for the gelatinase enzymes. (C) Stromelysin 1. Western blot analysis of the precursor (p) and active (e') forms of stromelysin 1 are shown by the enzyme standard (lane 5). Stromelysin 1 precursor released from control cultures is shown after 20 hours (lane 1) and 44 hours (lane 3) for comparison with similar secretagogue treated cultures at 20 hours (lane 2) and 44 hours (lane 4). Note depletion of the stromelysin 1 precursor in lane 4. The addition of 5 µg purified stromelysin 1 precursor (57 kDa; lane 6) was added to 50 µl conditioned 44 hour culture medium and secretagogue shown in lane 7. After incubation at 37°C for three hours the sample showed that some of the exogenous precursor had been converted to an active form of stromelysin 1 (45 kDa; lane 8), thereby demonstrating its proteolytic processing capacity for stromelysin 1.

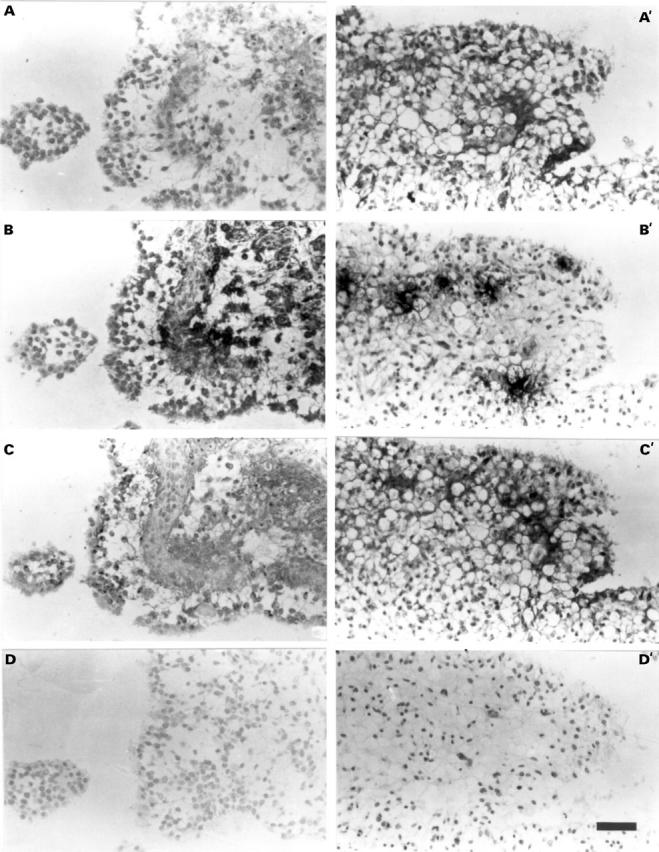

Figure 4 .

Immunolocalisation of MC tryptase, collagenase 1, and stromelysin 1 on consecutive tissue sections of rheumatoid synovial explants treated with MC secretagogue after 20 hours (A-D) or 44 hours (A'-D'). Positive immunostaining visualised by the darkly stained cells or matrix compared with control haematoxylin stained tissue sections shown in (D) and (D'). (A) and (A'). Immunolocalisation of collagenase 1. Note very little immunostaining at 20 hours (A) but both intracellular and extracellular staining at 44 hours (A'). (B) and (B') Immunolocalisation of MC tryptase. Both tissue sections at 20 hours (B) and 44 hours (B') show evidence of extracellular tryptase indicative of MC degranulation. Note the association or uptake of tryptase by the lining synovial cells in (B). (C) and (C') Immunolocalisation of stromelysin 1. Note that positive staining is mainly intracellular with weaker staining of matrix at 20 hours (C), whereas at 44 hours widespread extracellular immunostaining is evident (C'). (D) and (D') Haematoxylin stained control sections for (A)-(C), and (A')-(C'), respectively. Bar = 50 µm for all micrographs.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alter S. C., Metcalfe D. D., Bradford T. R., Schwartz L. B. Regulation of human mast cell tryptase. Effects of enzyme concentration, ionic strength and the structure and negative charge density of polysaccharides. Biochem J. 1987 Dec 15;248(3):821–827. doi: 10.1042/bj2480821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arend W. P., Dayer J. M. Inhibition of the production and effects of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor alpha in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Feb;38(2):151–160. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baggiolini M., Horisberger U., Martin U. Phagocytosis of mast cell granules by mononuclear phagocytes, neutrophils and eosinophils during anaphylaxis. Int Arch Allergy Appl Immunol. 1982;67(3):219–226. doi: 10.1159/000233022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkedal-Hansen H., Moore W. G., Bodden M. K., Windsor L. J., Birkedal-Hansen B., DeCarlo A., Engler J. A. Matrix metalloproteinases: a review. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med. 1993;4(2):197–250. doi: 10.1177/10454411930040020401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonassar L. J., Frank E. H., Murray J. C., Paguio C. G., Moore V. L., Lark M. W., Sandy J. D., Wu J. J., Eyre D. R., Grodzinsky A. J. Changes in cartilage composition and physical properties due to stromelysin degradation. Arthritis Rheum. 1995 Feb;38(2):173–183. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bridges A. J., Malone D. G., Jicinsky J., Chen M., Ory P., Engber W., Graziano F. M. Human synovial mast cell involvement in rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Relationship to disease type, clinical activity, and antirheumatic therapy. Arthritis Rheum. 1991 Sep;34(9):1116–1124. doi: 10.1002/art.1780340907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bromley M., Fisher W. D., Woolley D. E. Mast cells at sites of cartilage erosion in the rheumatoid joint. Ann Rheum Dis. 1984 Feb;43(1):76–79. doi: 10.1136/ard.43.1.76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu C. Q., Field M., Allard S., Abney E., Feldmann M., Maini R. N. Detection of cytokines at the cartilage/pannus junction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: implications for the role of cytokines in cartilage destruction and repair. Br J Rheumatol. 1992 Oct;31(10):653–661. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/31.10.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli S. J., Gordon J. R., Wershil B. K. Cytokine production by mast cells and basophils. Curr Opin Immunol. 1991 Dec;3(6):865–872. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(05)80005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli S. J. New concepts about the mast cell. N Engl J Med. 1993 Jan 28;328(4):257–265. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199301283280408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon J. R., Galli S. J. Mast cells as a source of both preformed and immunologically inducible TNF-alpha/cachectin. Nature. 1990 Jul 19;346(6281):274–276. doi: 10.1038/346274a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotis-Graham I., McNeil H. P. Mast cell responses in rheumatoid synovium. Association of the MCTC subset with matrix turnover and clinical progression. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Mar;40(3):479–489. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber B. L., Marchese M. J., Suzuki K., Schwartz L. B., Okada Y., Nagase H., Ramamurthy N. S. Synovial procollagenase activation by human mast cell tryptase dependence upon matrix metalloproteinase 3 activation. J Clin Invest. 1989 Nov;84(5):1657–1662. doi: 10.1172/JCI114344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber B., Poznansky M., Boss E., Partin J., Gorevic P., Kaplan A. P. Characterization and functional studies of rheumatoid synovial mast cells. Activation by secretagogues, anti-IgE, and a histamine-releasing lymphokine. Arthritis Rheum. 1986 Aug;29(8):944–955. doi: 10.1002/art.1780290802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeziorska M., Salamonsen L. A., Woolley D. E. Mast cell and eosinophil distribution and activation in human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. Biol Reprod. 1995 Aug;53(2):312–320. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod53.2.312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopicky-Burd J. A., Kagey-Sobotka A., Peters S. P., Dvorak A. M., Lennox D. W., Lichtenstein L. M., Wigley F. M. Characterization of human synovial mast cells. J Rheumatol. 1988 Sep;15(9):1326–1333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees M., Taylor D. J., Woolley D. E. Mast cell proteinases activate precursor forms of collagenase and stromelysin, but not of gelatinases A and B. Eur J Biochem. 1994 Jul 1;223(1):171–177. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb18980.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone D. G., Verbsky J. W., Dolan P. W. A lavage method for dynamic intraarticular monitoring of animal joints in situ: quantification and release kinetics of histamine after selective synovial mast cell activation by diverse secretagogues. J Lab Clin Med. 1991 Sep;118(3):269–279. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G., Docherty A. J., Hembry R. M., Reynolds J. J. Metalloproteinases and tissue damage. Br J Rheumatol. 1991;30 (Suppl 1):25–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz L. B. Mast cells: function and contents. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994 Feb;6(1):91–97. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90039-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subba Rao P. V., Friedman M. M., Atkins F. M., Metcalfe D. D. Phagocytosis of mast cell granules by cultured fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1983 Jan;130(1):341–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki K., Lees M., Newlands G. F., Nagase H., Woolley D. E. Activation of precursors for matrix metalloproteinases 1 (interstitial collagenase) and 3 (stromelysin) by rat mast-cell proteinases I and II. Biochem J. 1995 Jan 1;305(Pt 1):301–306. doi: 10.1042/bj3050301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow L. C., Lees M., Woolley D. E. Comparative studies of collagenase and stromelysin-1 expression by rheumatoid synoviocytes in vitro. Virchows Arch. 1995;425(6):569–576. doi: 10.1007/BF00199344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow L. C., Woolley D. E. Distribution, activation and tryptase/chymase phenotype of mast cells in the rheumatoid lesion. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Jul;54(7):549–555. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.7.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tetlow L. C., Woolley D. E. Mast cells, cytokines, and metalloproteinases at the rheumatoid lesion: dual immunolocalisation studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Nov;54(11):896–903. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.11.896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verbsky J. W., McAllister P. K., Malone D. G. Mast cell activation in human synovium explants by calcium ionophore A23187, compound 48/80, and rabbit IgG anti-human IgE, but not morphine sulfate. Inflamm Res. 1996 Jan;45(1):35–41. doi: 10.1007/BF02263503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wooley D. E. Mast cells in the rheumatoid lesion--ringleaders or innocent bystanders? Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Jul;54(7):533–534. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.7.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolley D. E., Tetlow L. C. Observations on the microenvironmental nature of cartilage degradation in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1997 Mar;56(3):151–161. doi: 10.1136/ard.56.3.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. J., Lark M. W., Chun L. E., Eyre D. R. Sites of stromelysin cleavage in collagen types II, IX, X, and XI of cartilage. J Biol Chem. 1991 Mar 25;266(9):5625–5628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe J. R., Taylor D. J., Wooley D. E. Mast cell products stimulate collagenase and prostaglandin E production by cultures of adherent rheumatoid synovial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1984 Jul 18;122(1):270–276. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(84)90470-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoffe J. R., Taylor D. J., Woolley D. E. Mast-cell products and heparin stimulate the production of mononuclear-cell factor by cultured human monocyte/macrophages. Biochem J. 1985 Aug 15;230(1):83–88. doi: 10.1042/bj2300083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Paulis A., Ciccarelli A., Marinò I., de Crescenzo G., Marinò D., Marone G. Human synovial mast cells. II. Heterogeneity of the pharmacologic effects of antiinflammatory and immunosuppressive drugs. Arthritis Rheum. 1997 Mar;40(3):469–478. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]