Abstract

OBJECTIVES—To investigate age related and site specific variations in turnover and chemistry of the collagen network in healthy tendons as well as the role of collagen remodelling in the degeneration of the supraspinatus tendon (ST-D) in rotator cuff tendinitis. METHODS—Collagen content and the amount of hydroxylysine (Hyl), hydroxylysylpyridinoline (HP), lysylpyridinoline (LP), and the degree of non-enzymatic glycation (pentosidine) were investigated in ST-D and in normal human supraspinatus (ST-N) and biceps brachii tendons (BT-N) by high-performance liquid chromatography. RESULTS—In BT-N, tendons that served as control tissue as it shows rarely matrix abnormalities, pentosidine levels rise linearly with age (20-90 years), indicating little tissue remodelling (resulting in an undisturbed accumulation of pentosidine). A similar accumulation was observed in ST-N up to 50 years. At older ages, little pentosidine accumulation was observed and pentosidine levels showed large interindividual variability. This was interpreted as remodelling of collagen in normal ST after age 50 years because of microruptures (thus diluting old collagen with newly synthesised collagen). All degenerate ST samples showed decreased pentosidine levels compared with age matched controls, indicating extensive remodelling in an attempt to repair the tendon defect. Collagen content and the amount of Hyl, HP, and LP of ST-N and BT-N did not change with age. With the exception of collagen content, which did not differ, all parameters were significantly (p<0.001) lower in BT-N. The ST-D samples had a reduced collagen content and had higher Hyl, HP, and LP levels than ST-N (p<0.001). CONCLUSIONS—Inasmuch as Hyl, HP, and LP levels in ST-N did not change with age, tissue remodelling as a consequence of microruptures does not seem to affect the quality of the tendon collagen. On the other hand, the clearly different profile of post-translational modifications in ST-D indicates that the newly deposited collagen network in degenerated tendons is qualitatively different. It is concluded that in ST-D the previously functional and carefully constructed matrix is replaced by aberrant collagen. This may result in a mechanically less stable tendon; as the supraspinatus is constantly subjected to considerable forces this could explain why tendinitis is mostly of a chronic nature. Keywords: collagen; tendons; crosslinks; pentosidine

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (244.4 KB).

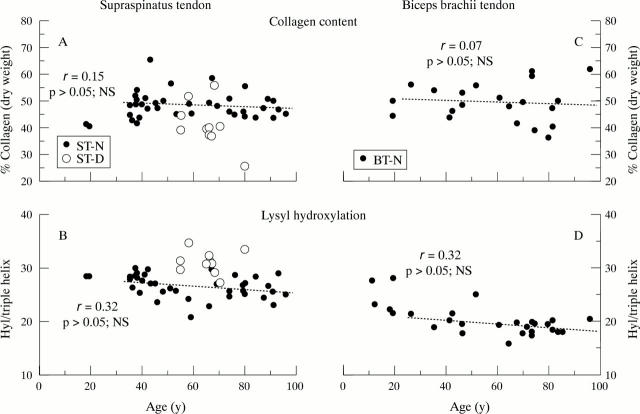

Figure 1 .

(A), (B): Collagen content and amount of hydroxylysine (Hyl) residues per collagen molecule in normal supraspinatus tendon (ST-N, filled circles) and degenerate supraspinatus tendon (ST-D, open circles) as a function of age. (C), (D): Collagen content and amount of Hyl residues per collagen molecule in normal biceps brachii tendon (BT-N, closed circles). Linear regression was performed on normal tendons from mature subjects, > 20 years only; no significant correlations with age were found.

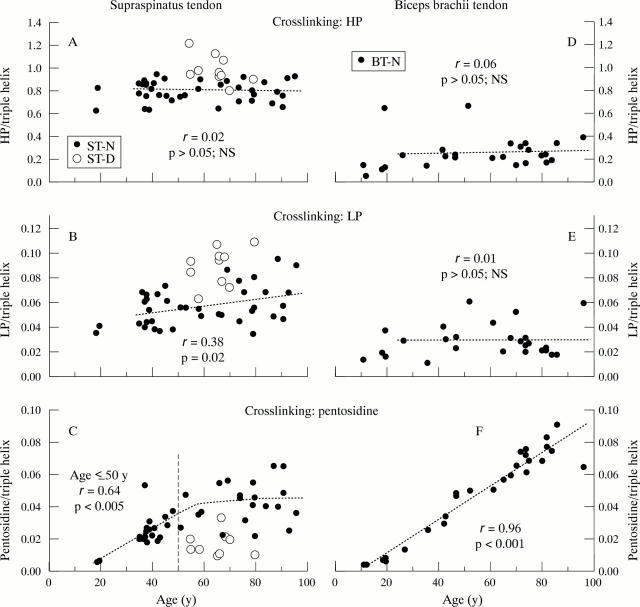

Figure 2 .

(A), (B), (C): Amounts of the crosslinks hydroxylysylpyridinoline (HP), lysylpyridinoline (LP), and pentosidine as a function of age in normal supraspinatus tendon (ST-N, filled circles) and degenerate supraspinatus tendon (ST-D, open circles). (D), (F): Amounts of HP, LP and pentosidine in normal biceps brachii tendon (BT-N, closed circles) with age. Data are expressed as mols of crosslink/mol of collagen. Linear regression analysis was performed on normal tendons (HP and LP: > 20 years only; pentosidine: < 50 years for ST-N, full age range for BT-N). In ST-N, a slight but significant increase of LP with age was observed. A high correlation was found between pentosidine levels and age of ST-N (age < 50 years) and BT-N (age 11-96 years); the slope of the regression line of ST-N between 20 and 50 years does not significantly differ from that of BT-N.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bailey A. J., Bazin S., Sims T. J., Le Lous M., Nicoletis C., Delaunay A. Characterization of the collagen of human hypertrophic and normal scars. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975 Oct 20;405(2):412–421. doi: 10.1016/0005-2795(75)90106-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. J., Light N. D. Intermolecular cross-linking in fibrotic collagen. Ciba Found Symp. 1985;114:80–96. doi: 10.1002/9780470720950.ch6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. J., Robins S. P., Balian G. Biological significance of the intermolecular crosslinks of collagen. Nature. 1974 Sep 13;251(5471):105–109. doi: 10.1038/251105a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey A. J., Robins S. P. Embryonic skin collagen. Replacement of the type of aldimine crosslinks during the early growth period. FEBS Lett. 1972 Apr 1;21(3):330–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(72)80195-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank R. A., Bayliss M. T., Lafeber F. P., Maroudas A., Tekoppele J. M. Ageing and zonal variation in post-translational modification of collagen in normal human articular cartilage. The age-related increase in non-enzymatic glycation affects biomechanical properties of cartilage. Biochem J. 1998 Feb 15;330(Pt 1):345–351. doi: 10.1042/bj3300345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank R. A., Beekman B., Verzijl N., de Roos J. A., Sakkee A. N., TeKoppele J. M. Sensitive fluorimetric quantitation of pyridinium and pentosidine crosslinks in biological samples in a single high-performance liquid chromatographic run. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 1997 Dec 5;703(1-2):37–44. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(97)00391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank R. A., Jansen E. J., Beekman B., te Koppele J. M. Amino acid analysis by reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography: improved derivatization and detection conditions with 9-fluorenylmethyl chloroformate. Anal Biochem. 1996 Sep 5;240(2):167–176. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard M. D., Sattelle L. M., Hazleman B. L. The long-term outcome of rotator cuff tendinitis--a review study. Br J Rheumatol. 1988 Oct;27(5):385–389. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/27.5.385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chard M. D., Wright J. K., Hazleman B. L. Isolation and growth characteristics of adult human tendon fibroblasts. Ann Rheum Dis. 1987 May;46(5):385–390. doi: 10.1136/ard.46.5.385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cofield R. H. Rotator cuff disease of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985 Jul;67(6):974–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton S., Cawston T. E., Riley G. P., Bayley I. J., Hazleman B. L. Human shoulder tendon biopsy samples in organ culture produce procollagenase and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases. Ann Rheum Dis. 1995 Jul;54(7):571–577. doi: 10.1136/ard.54.7.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyer D. G., Blackledge J. A., Thorpe S. R., Baynes J. W. Formation of pentosidine during nonenzymatic browning of proteins by glucose. Identification of glucose and other carbohydrates as possible precursors of pentosidine in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jun 25;266(18):11654–11660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre D. Collagen cross-linking amino acids. Methods Enzymol. 1987;144:115–139. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(87)44176-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glimcher M. J., Shapiro F., Ellis R. D., Eyre D. R. Changes in tissue morphology and collagen composition during the repair of cortical bone in the adult chicken. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980 Sep;62(6):964–973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson D. A., Eyre D. R. Molecular site specificity of pyridinoline and pyrrole cross-links in type I collagen of human bone. J Biol Chem. 1996 Oct 25;271(43):26508–26516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.43.26508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henkel W. Cross-link analysis of the C-telopeptide domain from type III collagen. Biochem J. 1996 Sep 1;318(Pt 2):497–503. doi: 10.1042/bj3180497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jobe C. M. Superior glenoid impingement. Current concepts. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996 Sep;(330):98–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohn R. R. Effects of age and diabetes mellitus on cyanogen bromide digestion of human dura mater collagen. Connect Tissue Res. 1983;11(2-3):169–173. doi: 10.3109/03008208309004852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LIBBY W. F., BERGER R., MEAD J. F., ALEXANDER G. V., ROSS J. F. REPLACEMENT RATES FOR HUMAN TISSUE FROM ATMOSPHERIC RADIOCARBON. Science. 1964 Nov 27;146(3648):1170–1172. doi: 10.1126/science.146.3648.1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last J. A., Armstrong L. G., Reiser K. M. Biosynthesis of collagen crosslinks. Int J Biochem. 1990;22(6):559–564. doi: 10.1016/0020-711x(90)90031-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroudas A., Palla G., Gilav E. Racemization of aspartic acid in human articular cartilage. Connect Tissue Res. 1992;28(3):161–169. doi: 10.3109/03008209209015033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monnier V. M., Sell D. R., Nagaraj R. H., Miyata S., Grandhee S., Odetti P., Ibrahim S. A. Maillard reaction-mediated molecular damage to extracellular matrix and other tissue proteins in diabetes, aging, and uremia. Diabetes. 1992 Oct;41 (Suppl 2):36–41. doi: 10.2337/diab.41.2.s36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neer C. S., 2nd Impingement lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983 Mar;(173):70–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimni M. E. Collagen: structure, function, and metabolism in normal and fibrotic tissues. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1983 Aug;13(1):1–86. doi: 10.1016/0049-0172(83)90024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozaki J., Fujimoto S., Nakagawa Y., Masuhara K., Tamai S. Tears of the rotator cuff of the shoulder associated with pathological changes in the acromion. A study in cadavera. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988 Sep;70(8):1224–1230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poppen N. K., Walker P. S. Forces at the glenohumeral joint in abduction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1978 Sep;(135):165–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prockop D. J., Kivirikko K. I. Collagens: molecular biology, diseases, and potentials for therapy. Annu Rev Biochem. 1995;64:403–434. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.64.070195.002155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiser K. M. Nonenzymatic glycation of collagen in aging and diabetes. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1991 Jan;196(1):17–29. doi: 10.3181/00379727-196-43158c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricard-Blum S., Bresson-Hadni S., Vuitton D. A., Ville G., Grimaud J. A. Hydroxypyridinium collagen cross-links in human liver fibrosis: study of alveolar echinococcosis. Hepatology. 1992 Apr;15(4):599–602. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840150408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G. P., Harrall R. L., Constant C. R., Chard M. D., Cawston T. E., Hazleman B. L. Glycosaminoglycans of human rotator cuff tendons: changes with age and in chronic rotator cuff tendinitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Jun;53(6):367–376. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.6.367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley G. P., Harrall R. L., Constant C. R., Chard M. D., Cawston T. E., Hazleman B. L. Tendon degeneration and chronic shoulder pain: changes in the collagen composition of the human rotator cuff tendons in rotator cuff tendinitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1994 Jun;53(6):359–366. doi: 10.1136/ard.53.6.359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell D. R., Carlson E. C., Monnier V. M. Differential effects of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus on pentosidine formation in skin and glomerular basement membrane. Diabetologia. 1993 Oct;36(10):936–941. doi: 10.1007/BF02374476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell D. R., Monnier V. M. End-stage renal disease and diabetes catalyze the formation of a pentose-derived crosslink from aging human collagen. J Clin Invest. 1990 Feb;85(2):380–384. doi: 10.1172/JCI114449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel K. G., Koob T. J. Structural specialization in tendons under compression. Int Rev Cytol. 1989;115:267–293. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)60632-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams I. F., McCullagh K. G., Silver I. A. The distribution of types I and III collagen and fibronectin in the healing equine tendon. Connect Tissue Res. 1984;12(3-4):211–227. doi: 10.3109/03008208409013684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C., Niu C., Bodo M., Gabriel E., Notbohm H., Wolf E., Müller P. K. Fulvic acid supplementation and selenium deficiency disturb the structural integrity of mouse skeletal tissue. An animal model to study the molecular defects of Kashin-Beck disease. Biochem J. 1993 Feb 1;289(Pt 3):829–835. doi: 10.1042/bj2890829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von der Mark K. Localization of collagen types in tissues. Int Rev Connect Tissue Res. 1981;9:265–324. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-363709-3.50012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]